Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

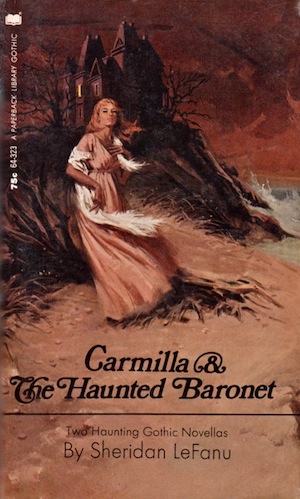

This week, we continue with J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, first published as a serial in The Dark Blue from 1871 to 1872, with Chapters 11-12. Spoilers ahead!

“I was only too happy, after all, to have secured so charming a companion for my dear girl.”

As the carriage wheels on towards long-abandoned Karnstein, General Spielsdorf begins his tale of woe. His ward Bertha was looking forward to her visit with Laura, but first she and the General were obliged to attend the grand fetes given by Count Carlfeld in honor of Grand Duke Charles.

Carlfeld’s hospitalities, always regal in scale, culminate in a masquerade ball complete with fireworks and music by the finest performers in Europe. As the General and Bertha stroll about the brilliantly illuminated gardens, he notices a magnificently dressed and masked young lady observing his ward with interest–to be sure, the unmasked Bertha looks in her excitement and delight more lovely than ever. The young lady’s chaperone, also masked, is a woman whose stateliness of attire and demeanor mark her as a person of rank.

As Bertha rests between dances, the masked young lady takes a seat beside her. Her chaperone joins the General and calls him by name as if they were old friends. They must be old friends, the General concludes, because the chaperone alludes to many scenes and incidents in his past. “Very adroitly and pleasantly” she evades his attempts to discover her name. Meanwhile, the young lady (whom the chaperone addresses as Millarca) has introduced herself to Bertha as the daughter of the General’s mysterious acquaintance. Her lively wit and evident admiration of Bertha soon seal their friendship. She unmasks to reveal a beauty of powerful attraction; it seems to the General that Bertha fall under its spell, and that in her turn Millarca has “lost her heart” to Bertha.

He continues trying to wheedle Millarca’s mother for her name. She continues to thwart him. A gentleman dressed in black, with “the most deadly pale face” the General ever saw “except in death,” interrupts their flirtation. Bowing to the lady, he begs to say “a very few words which may interest her.” The lady steps aside with him and engages for some minutes in earnest conversation. When they return, the pale man says he will inform “Madame la Comtesse” when her carriage is at the door and takes leave with another bow.

The General sweeps Madame a low bow and hopes she won’t be leaving Count Carlfeld’s chateau for long. Perhaps for a few hours, perhaps for several weeks, she replies. It was unlucky the pale gentleman spoke to her just now. But does the General now know her name?

He does not.

He will, Madame says, but not at present. They may be older, better friends than he expects; in three weeks or so she hopes to pass his schloss and renew their friendship. Now, however, the news she’s just received requires her to travel with the greatest dispatch. Compelled to go on concealing her identity, she is doubly embarrassed by the singular request she must make. Millarca has had a fall from horseback that has so shocked her nerves that she must not undertake the exertion of such a journey as Madame’s–a mission in fact of “life and death.” Moreover, an unnamed someone might have recognized her when for a thoughtless moment earlier she removed her mask. Neither she not her daughter can safely remain with Count Carlfeld, who by the way knows her reasons. If only the General could take charge of Millarca until her return!

That it’s a strange and audacious request Madame fully acknowledges, but she throws herself on the General’s chivalry. At the same time, Bertha beseeches him to invite her new friend for a visit. Assailed by both ladies, and reassured by the “elegance and fire of high birth” in Millarca’s visage, the General puts aside his qualms and issues the invitation.

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

Madame explains the situation to her daughter, who will observe the same secrecy as Madame about their identity. The pale gentleman returns and conducts Madame from the room with such ceremony as convinces the General of her importance. He does not “half like” his hastily assumed guardianship, but makes the best of it.

Millarca watches her mother depart and sighs plaintively when Madame doesn’t look back to take leave. Her beauty and unhappiness make the General regret his unspoken hesitancy to host her. He begins to make amends by yielding to the girls’ wish to return to the festivities. As Millarca amuses them with stories about the great people around them, the General begins to think she will give life to their sometimes lonely schloss.

The ball ends only with the dawn. At that point he realizes Millarca has somehow gotten separated from them. His efforts to find her are in vain, and he keenly feels his folly in taking charge of her. Around two that afternoon, a servant informs them a young lady “in great distress” is looking for the General Spielsdorf.

Restored to her new friends, Millarca explains that after losing them she fell asleep in the housekeeper’s room; what with the exertions of the ball, she slept long. That day she goes home with the General and Bertha. At the time he is happy to “have secured so charming a companion for [his] dear girl.”

Now, as he exclaims to Laura’s father, “Would to heaven we had lost her!”

This Week’s Metrics

By These Signs Shall You Know Her: The vampire has an extremely limited set of aliases. And even if she isn’t completely nocturnal, you’re not likely to find her at dawn.

Libronomicon: The General says that Count Carlfeld “has Aladdin’s lamp,” presumably a literary reference rather than a literal one.

Anne’s Commentary

These two chapters, comprising the first part of the General’s narrative of loss, indicate that Carmilla has a well-practiced modus operandi for obtaining “beloved” victims. As opposed, you know, to the “quick snack” victims she can apparently leap upon as a leopard leaps upon an impala, pure unceremonious predation. As an avid student of the unnatural history of vampires, I have questions. Does Carmilla need an invitation before she can enter a victim’s house, a common limitation imposed on the undead? She and her cohorts go to elaborate lengths to get her an invite to Laura and Bertha’s homes. We don’t know if her peasant snacks welcome her into their hovels. Given her crazy-powerful allure, she might just have to smile at a window or knock on a door to have the barriers thrown wide. I’m more inclined to think, though, that the “lower-class” victims can be throttled and bled at will, no effort at seduction necessary.

Whereas “upper-class” victims may both merit and require seduction. Class does seem to be an issue here. To the aristocratic Countess Mircalla of Karnstein, peasants were always objects of exploitation (recall her ire over the presumptuous peddler), so no wonder if they’re now mere food. She would never fall in love with a peasant, never make one the object of erotic obsession, to be courted at luxurious yet intense leisure. Her love, be it genuine emotion or a slow pseudo-amatory predation, is reserved for young ladies of quality, of a certain rank in society, not necessarily noble but able to live in schlosses and associate with the nobility. A young lady like Bertha or Laura. And Laura adds to her allure the fact that she is related to the Karnsteins, hence however distantly of noble lineage–and of the same noble lineage as Carmilla! Nothing legally incestuous here, given the generational stretch between Carmilla and Laura. Still, an added titillation?

I wonder if Carmilla has come to view Laura as a sort of ultimate beloved victim, maybe having learned of her existence from Bertha, who would have learned something of her future hostess’s antecedents from the General? Bertha couldn’t have been a spur-of-the-moment infatuation, either–the ballroom attack must have been orchestrated in advance, or else how would “Madame” have had time to gather such intimate intelligence on the General? Unless “Madame” is so powerfully telepathic she could plumb the General’s memory to depths he himself hadn’t visited for years…

Questions, questions! Who are these people who aid and enable Carmilla in her sinister amours? The head of the entourage appears to be her “mother,” the enigmatic noblewoman of many critical errands. Is she mortal or undead? I’d guess mortal, but it’s just a guess. What about the pale gentleman at the ball? He’s so damn pale I vote he’s a (poorly fed?) vampire? Or working for vampires, he might be a human who rarely gets out during the day, or who “donates” blood to his mistress at a pinch? The turbaned black woman glimpsed in Carmilla’s carriage? In the story she would figure only as a heavy-handed dash of exotica if it weren’t for the looks of derision and fury she lances at Carmilla and “Mom.” Such animosity towards her–employers, companions?–struck Mademoiselle La Fontaine forcibly. “Mom” also has telling lapses in maternal affection, leaving her fragile “daughter” behind with the most perfunctory of caresses and no long-backward gazes. “Mom’s” manservants are an “ill-looking pack” of “ugly hangdog-looking fellows” with “strangely lean, and dark, and sullen” faces.

No one in the entourage, in fact, seems to enjoy their job. Certainly no one displays any Renfield-like devotion towards their vampire mistress. Maybe they aren’t insane enough to love Carmilla? Maybe she relies entirely on some harsh compulsion to subjugate them, no tantalizing promises of life eternal?

Questions!

Thus far into the General’s narration, Laura’s father hasn’t exclaimed at the similarity between Millarca’s insinuation into the General’s household and Carmilla’s into his own, nor has Laura marveled at the parallels. Nobody’s caught on to the anagrammatic names, either: Mircalla, Millarca, Carmilla, see, see? They must all be the same person who either has little imagination in inventing aliases or who is under some magical obligation to retain her birth name, however scrambled.

I’ll let the anagram thing go. I can allow that Dad may be suppressing his recognition of the parallels until he has the General alone. The alternative is that he’s thick as a brick, dense as a year-old fruitcake. The General was less dense than Dad about taking charge of an unknown girl – at least he had initial doubts enough to feel all curmudgeonly and paranoid when Millarca’s befuddling charm kicked in.

Much that seems implausible in Carmilla may be written off to the effect of her vampiric allure and cunning. Nevertheless, what must the anguish of the two impeccable patriarchs be when they realize that they’ve failed to protect their own young ladies by getting all patriarchal about a predator in young-lady disguise? In 19th-century tales, and often in later ones, the stalwart male guardians of female vampire victims feel booted in the stalwart male parts when a male bloodsucker slips through their defenses: See Stoker’s Dracula for prime examples.

Is the horror even greater when the innocence-defiling monster is female? Especially one you might have kinda fancied yourself?

Questions!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I do like the General. It’s possible that he’s telling the story of the biggest mistake of his life in a way that makes him look as good as he possibly could—but his response to Carmilla’s/Millarca’s con rings true. If she-of-the-terrible-aliases were undead today, she’d be cornering you at a party to urge that if you invest right now, this exiled German countess will pay you back incredible dividends.

In other words, seeing two versions of the con makes it even more obvious how much it has in common with real-life cons. Pretending to be someone you know, check. Immediate sense of undue closeness, check. Time pressure to make important decisions, check. Using social norms as a hack even while violating them, check. That she happens to be after blood rather than money is a side note—at least for her.

I wonder if she helped get the General that “nobody” invitation to Jareth’s ball, too. Has she got some hold on Count Carlfeld? It does sound like a fabulous party, aside from the vampires.

Five minutes to think would give the General plenty of chance to pick up the holes in the “chaperone’s” explanations. Does their host know who she is? Why, having feared that the General recognized her, does she drop so many ostensible clues that would help him reconstruct her identity? Why can’t she reveal herself to such a trustworthy friend in order to assure her daughter a place to stay? Why is she willing to trust him with her daughter but not her name? But by the time he gets those five minutes, asking these questions in more than the most perfunctory way would lead him to an untenable dilemma. It’s well-done, rather moreso than the contrived set-up that inserts Carmilla into Laura’s household. But then, Laura’s family doesn’t go to parties.

I do have questions for Carmilla. Mostly: why, with all this care put into trapping her prey, does she use such transparent aliases? Is she also compelled to leave behind riddles? But I suppose it’s related to the occasional compulsion to confess her deadly passions to Laura. Traditionally vampires do suffer from such requirements. Anagrams and sleeping till mid-afternoon are honestly less disruptive to one’s hunting routine than counting grains of spilled rice and burning under the least hint of sunlight.

It’s hard to tell what Bertha thinks of all this, other than that Millarca is gorgeous and it would be nice to have a friend. Love at first sight, the General admits—though not actually first sight for Millarca, of course. But the “stranger” has “lost her heart,” and all is lost.

I wonder, too, if Carmilla first learned of Laura from Bertha’s anticipation of her upcoming visit. Perhaps she was jealous at first, that jealousy then transmuting to the foundation for her next obsession. Is she always quite so serial in her affections, or does she sometimes go through decades of unrewarding one-night murders?

Hopefully, the General will soon pause for breath, and we’ll get to hear what Laura and her father think of this all-too-familiar story. Hopefully, they’re good at anagram puzzles!

Next week, we round out National Poetry Month with a vampire-ish poem. Join us for Crystal Sidell’s “The Truth About Doppelgangers”!

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out July 26th. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.