When at college, I had a friendly book-rivalry with another student. I’d been an insatiable bookworm through my school years, and he was the first person I met who had read as widely as me. But we hailed from different backgrounds: he was a polyglot Canadian who had studied in Russia, while I was a working-class British girl who had barely travelled outside the UK. And so we had very different areas of “expertise,” in which we educated the other by swapping books.

My friend introduced me to novels I remember vividly even now: Andrei Bely’s Petersburg, Ivo Andrić’s The Bridge on the Drina (memorable for its excruciating scene of impalement), and Bruno Schulz’s The Street of Crocodiles. These books all rocked my world—but one would change my life.

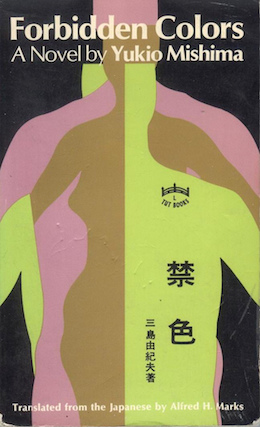

Forbidden Colors, by Yukio Mishima, is both dazzling and cruel—as I later discovered all Mishima’s works are.

Written in Japan in 1951, Forbidden Colors is narrated by an aging literary grandee named Shunsuke. On vacation, he meets an engaged couple, and becomes captivated by the handsome husband-to-be. The young man, Yuichi, is gay (as author Mishima himself was) and under Shunsuke’s malign tutelage he launches into a life of multiple identities: married, the object of desire of an older woman, and becoming the darling of the Tokyo underground gay scene.

In many ways, it’s an obnoxious book—dripping with Shunsuke’s misogyny. And Mishima himself was a controversial, even repellent, figure: obsessed with bodily perfection, militarism, and imperialism. He committed ritual suicide after staging a failed coup. Yet this ugly tale is told in some of the most exquisite prose I had ever read, beautifully rendered by translator Alfred Marks.

And running through all Mishima’s work is a desire I could relate to: his life-long search for identity and truth to oneself. “The purest evil that human efforts could attain,” he writes in Runaway Horses, a book in his masterpiece Sea of Fertility tetralogy, “was probably achieved by those men who made their wills the same and who made their eyes see the world in the same way, men who went against the pattern of life’s diversity.”

Forbidden Colors made me devour everything else that Mishima wrote. And then I explored the great 19th and 20th-century authors who came before him: Kawabata, Endo, Tanizaki, Akutagawa, Miyazawa, and Soseki. I discovered Edogawa Ranpo, a writer and critic who took his pen-name from the American author he most admired, Edgar Allan Poe.

The more I read, the more conscious I became that these books were written in a language profoundly different from English. I wanted to move to Japan and learn Japanese, so I could read them in the original. And I was lucky enough to win a two-year scholarship that let me do just that.

I spent my days beating my head against my desk in a strict, old-fashioned language school—I’m an abject linguist. But this beautiful, complex language went in eventually. I let myself fall in love with the rituals of writing. I practiced kanji characters and studied calligraphy. I even acquired a haiku instructor, the fierce and fabulous Mogi-sensei.

At the weekends and during school holidays I explored. I wanted to experience the aesthetics of the Japan that Mishima writes about with such exquisite chill. A world where divisions between one human heart and another are literally paper-thin—the sliding shoji screens—and yet unbridgeably wide. Where one character yearns for a beautiful death, as elegant and easy as a silk kimono sliding off a smooth lacquered surface.

So I went to Kyoto, to the ancient capital of Nara, to the mountain forests for momiji—viewing the changing autumn leaves. A favourite weekend retreat from Tokyo was Kamakura, with its many monasteries and quiet bamboo groves. In Tokyo, I lived around the corner from the art-deco Teien Museum, a former imperial palace stuffed with refined treasures. At New Year, I performed hatsumode (first-visit) to the temple of Sengaku-ji, where the 47 rõnin are buried alongside the master they avenged.

But of course this is only one side of Japan—the side that the Western imagination fixes on most avidly. And Japan’s contemporary fiction helped me explore the modern country that I lived in. What came after Mishima was Oe, Murakami Haruki, Murakami Ryu, Yoshimoto, and Kirino.

I went to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In Tokyo I saw the gaisensha propaganda trucks of the right-wing nationalist groups that share principles Mishima might have understood: imperialism and military apologism. In Osaka I hung out with a sushi-chef who catered to yakuza. With Japanese friends and alone, I visited hostess bars and dive bars.

I left Japan after five years feeling alternately like I understood the country as intimately as a friend, and yet that I would never understand it at all. Now, when I want to remember Japan, I can either pull out my photo album or turn to my bookshelf. To me, books are countries. You inhabit them briefly, but intensely.

And Mishima? Well, his prose is so exquisite and archaic, that even at my most proficient in Japanese I still couldn’t make head or tail of Forbidden Colours!

Vic James is a current affairs TV director who loves stories in all their forms, and Gilded Cage is her debut novel. She as twice judged the Guardian’s Not the Booker Prize, has made films for BBC1, BBC2, and Channel 4 News, and is a huge Wattpadd.com success story. Under its previous title, Slavedays, her book was read online over a third of a million times in first draft. And it went on to win Wattpad’s Talk of the Town award in 2015—on a site showcasing 200 million stories. Vic James lives and works in London. Say hello to Vic on Twitter @DrVictoriaJames and on Facebook.

Vic James is a current affairs TV director who loves stories in all their forms, and Gilded Cage is her debut novel. She as twice judged the Guardian’s Not the Booker Prize, has made films for BBC1, BBC2, and Channel 4 News, and is a huge Wattpadd.com success story. Under its previous title, Slavedays, her book was read online over a third of a million times in first draft. And it went on to win Wattpad’s Talk of the Town award in 2015—on a site showcasing 200 million stories. Vic James lives and works in London. Say hello to Vic on Twitter @DrVictoriaJames and on Facebook.