If, like me, you once tried to plant jelly beans in your backyard in the hopes that they would create either a magical jelly bean tree or summon a giant talking bunny, because if it worked in fairy tales it would of course work in an ordinary backyard in Indiana, you are doubtless familiar with the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, a tale of almost but not quite getting cheated by a con man and then having to deal with the massive repercussions.

You might, however, be a little less familiar with some of the older versions of the tale—and just how Jack initially got those magic beans.

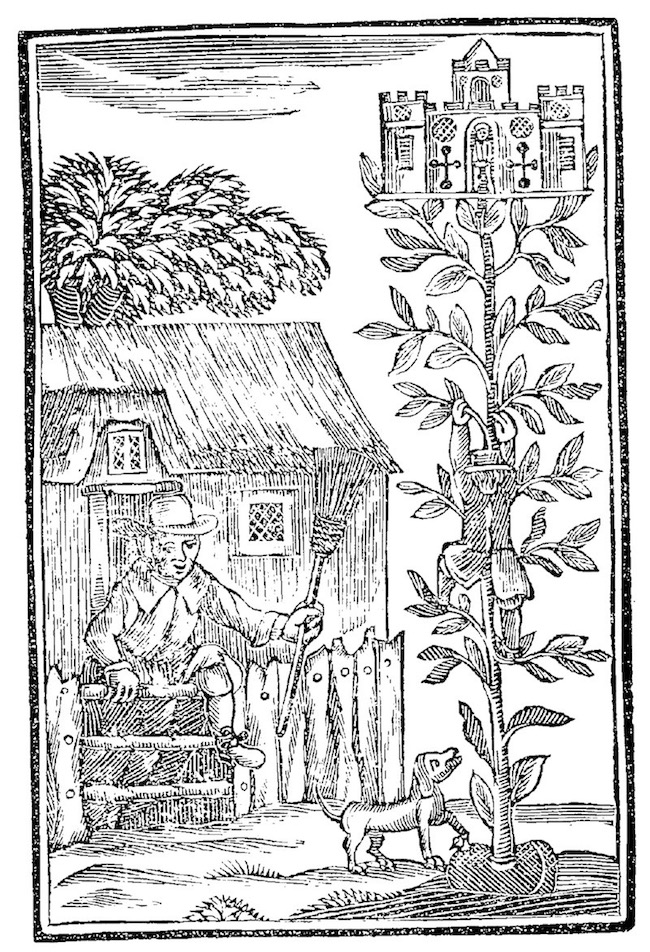

The story first appeared in print in 1734, during the reign of George II of England, when readers could shill out a shilling to buy a book called Round about our Coal Fire: Or, Christmas Entertainments, one of several self-described “Entertaining Pamphlets” printed in London by a certain J. Roberts. The book contained six chapters on such things as Christmas Entertainments, Hobgoblins, Witches, Ghosts, Fairies, how people were a lot more hospitable and nicer in general before 1734, and oh yes, the tale of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean, and how he became Monarch of the Universe. It was ascribed to a certain Dick Merryman—a name that, given the book’s interest in Christmas and magic, seems quite likely to have been a pseudonym—and is now available in what I am assured is a high quality digital scan from Amazon.com.

(At $18.75 per copy I didn’t buy it. You can find plenty of low quality digital scans of this text in various places in the internet.)

The publishers presumably insisted on adding the tale in order to assure customers that yes, they were getting their full shilling’s worth, and also, to try to lighten up a text that starts with a very very—did I mention very—lengthy complaint about how nobody really celebrates Christmas properly anymore, by which Dick Merryman means that people aren’t serving up as much fabulous free food as they used to, thus COMPLETELY RUINING CHRISTMAS FOR EVERYONE ELSE, like, can’t you guys kill just a few more geese, along with complaining that people used to be able to pay their rent in kind (that is, with goods instead of money) with the assurance that they’d be able to eat quite a lot of it at Christmas. None of this is as much fun as it sounds, though the descriptions of Christmas games might interest some historians.

Also, this:

As for Puffs in the Corner, that is a very harmless Sport, and one may ramp at it as much as one will; for at this Game when a Man catches his Woman, he may kiss her ’till her Ears crack, or she will be disappointed if she is a Woman of any Spirit; but if it is one who offers at a Struggle and blushes, then be assured she is a Prude, and though she won’t stand a Buss in publick, she’ll receive it with open Arms behind the Door, and you may kiss her ’till she makes your Heart ake.

….Ok then.

This is all followed by some chatter and about making ladies squeak (not a typo) and what to do if you find two people in bed during a game of hide and seek, and also, hobgoblins, and witches, and frankly, I have to assume that by the time Merryman finally gets around to telling Jack’s tale—page 35—most readers had given up. I know I almost did.

The story is supposedly related by Gaffer Spiggins, an elderly farmer who also happens to be one of Jack’s relatives. I say, supposedly, in part because by the end of the story, Merryman tells us that he got most of the story from the Chit Chat of an old nurse and the Maggots in a Madman’s brain. I suppose Gaffer Spiggins might be the madman in question, but I think it’s more likely that by the time he finally got to the end, Merryman had completely forgotten the start of his story. Possibly because of Maggots, or more likely because the story has the sense of being written very quickly while very drunk.

In any case, being Jack’s relative is not necessarily something to brag about. Jack is, Gaffer Spiggins assures us, lazy, dirty, and dead broke, with only one factor in his favor: his grandmother is an Enchantress. As the Gaffer explains:

for though he was a smart large boy, his Grandmother and he laid together, and between whiles the good old Woman instructed Jack in many things, and among the rest, Jack (says she) as you are a comfortable Bed-fellow to me —

Cough.

Uh huh.

Anyway. As thanks for being a good bedfellow, the grandmother tells Jack that she has an enchanted bean that can make him rich, but refuses to give him the bean just yet, on the basis that once he’s rich, he will probably turn into a Rake and desert her. It’s just barely possible that whoever wrote this had a few issues with men. The grandmother then threatens to whip him and calls him a lusty boy before announcing that she loves him too much to hurt him. I think we need to pause for a few more coughs, uh huhs and maybe even an AHEM. Fortunately before this can all get even more awkward and uncomfortable (for the readers, that is), Jack finds the bean and plants it, less out of hope for wealth and more from a love of beans and bacon. In complete contrast to everything I’ve ever tried to grow, the plant immediately springs up smacking Jack in the nose and making him bleed. Instead of, you know, TRYING TO TREAT HIS NOSEBLEED the grandmother instead tries to kill him, which, look, I really think we need to have a discussion about some of the many, many unhealthy aspects of this relationship. Jack, however, has no time for that. He instead runs up the beanstalk, followed by his infuriated grandmother, who then falls off the beanstalk, turns into a toad, and crawls into a basement—which seems to be a bit of an overreaction.

In the meantime, the beanstalk has now grown 40 miles high and already attracting various residents, inns, and deceitful landlords who claim to be able to provide anything in the world but when directly asked, admit that they don’t actually have any mutton, veal, or beef on hand. All Jack ends up getting is some beer.

Which, despite being just brewed, must be amazing beer, since just as he drinks it, the roof flies off, the landlord is transformed into a beautiful lady, with a hurried, confusing and frankly not all that convincing explanation that she used to be his grandmother’s cat. As I said, amazing beer. Jack is given the option of ruling the entire world and feeding the lady to a dragon. Jack, sensibly enough under the circumstances, just wants some food. Various magical people patiently explain that if you are the ruler of the entire world, you can just order some food. Also, if Jack puts on a ring, he can have five wishes. It will perhaps surprise no one at this point that he wishes for food, and, after that, clothing for the lady, music, entertainment, and heading to bed with the lady. The story now pauses to assure us that the bed in question is well equipped with chamberpots, which is a nice realistic touch for a fairy tale. In the morning, they have more food—a LOT more food—and are now, apparently, a prince and princess—and, well. There’s a giant, who says:

Fee, fow, fum—

I smell the blood of an English-Man,

Whether he be alive or dead,

I’ll grind his Bones to make my Bread.

I would call this the first appearance of the rather well known Jack and the Beanstalk rhyme, if it hadn’t been mostly stolen from King Lear. Not bothering to explain his knowledge of Shakespeare, the giant welcomes the two to the castle, falls instantly in love with the princess, but lets them fall asleep to the moaning of many virgins. Yes. Really. The next morning, the prince and princess eat again (this is a story obsessed with food), defeat the giant, and live happily ever after—presumably on top of the beanstalk. I say presumably, since at this point the author seems to have entirely forgotten the beanstalk or anything else about the story, and more seems interested in swiftly wrapping things up so he can go and complain about ghosts.

Merryman claimed to have heard portions of this story from an old nurse, presumably in childhood, and the story does have a rather childlike lack of logic to it, particularly as it springs from event to event with little explanation, often forgetting what happened before. The focus on food, too, is quite childlike. But with all of the talk of virgins, bedtricks, heading to bed, sounds made in bed, and violence, not to mention all of the rest of the book, this does not seem to be a book meant for children. Rather, it is a book that looks back nostalgically at a better, happier time—read: prior to the reign of the not overly popular George II of Great Britain. I have no proof that Merryman, whatever his real name was, participated in the Jacobite rebellion that would break out just a couple of years after this book’s publication, but I can say he would have felt at least a small tinge of sympathy, if not more, for that cause. It’s a book that argues that the wealthy are not fulfilling their social responsibilities, that hints darkly that the wealthy can be easily overthrown, and replaced by those deemed socially inferior.

So how exactly did this revolutionary tale get relegated to the nursery?

We’ll chat about that next week.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

Huh. There are, or were, “Jack Tales” all over the mountains of the southeast US that go back centuries, to England. IIRC, someone collected them into a book a hundred years or so ago.

Oh my! This story is definitely not for children and makes no sense by the time you get to the end. It is a story with food and chamber pots though which weirdly a lot of adventures skip right over . I know if I went on an adventure I’d need to eat and go to the bathroom. I don’t need details I’m good with just knowing they’re around.

So obsession with food? Famines in 1690s-1710 in Northern England and Scotland; killed up to 15 million people in Northern England/Scotland (also in Finland, Estonia, most of Northern Europe, Northern France… wide-spread starvation). Another one hit in the 1720s in the English Midlands.

About that beer: One of the reasons for the original German beer purity laws is that a lot of people were using henbane instead of hops to flavor their brew. Depending on the species, henbane can be kill-you-dead poisonous or even psychoactive. I’m just saying.

Paused over this article thinking “I’ve read Perrault, so that’s covered … Grimm, then? no … Anderson? not there either”. Somehow never noticed this didn’t turn up in any of them; good catch, and some interesting history to the tale.

I never planted jelly beans in the backyard, but I planted empty Bud cans in the hope of growing an Anheuser Busch.

@1. “The Jack Tales” were collected from a North Carolina family by Richard Chase who published the collection in 1943. They are written in dialect and are especially great when read out-loud.

I have no proof that Merryman, whatever his real name was, participated in the Jacobite rebellion that would break out just a couple of years after this book’s publication, but I can say he would have felt at least a small tinge of sympathy, if not more, for that cause. It’s a book that argues that the wealthy are not fulfilling their social responsibilities, that hints darkly that the wealthy can be easily overthrown, and replaced by those deemed socially inferior.

The Jacobites were really, really, really not keen on the idea of the wealthy being overthrown and replaced by those deemed socially inferior. They were supporters of the exiled Stuart monarchy, not Levellers.The Levellers had been on the other side in the Civil War, along with the Diggers and all the other radical groups, that had ended up with a Stuart monarch (who claimed the Divine Right to rule) being executed for tyranny and replaced by a bunch of commoners led by a Huntingdonshire farmer called Cromwell.

Shorter version: don’t assume that all rebels are egalitarians. The Jacobites weren’t, any more than the Confederates with whom they shared so much in common.

@8: No indeed, but Merryman’s position doesn’t seem to be egalitarian. He’s ok with there BEING a ruling class, he just thinks that privilege comes with obligations that the existing upper class aren’t fulfilling, and that they should be made to or replaced – and that things were better in the old days. None of which is at all incompatible with Jacobitism, especially since people with ANY kind of grudge against the government and the elite often hitched their cause to the Jacobite wagon.

Arn’t tings always better “in the good old days.” being an old man I know this to be true, just like my father before me and his father before him …. :)

Food, Sex, and Violence? This could have been a GRRM story ;-)

Czanne @3, so nice surprise to see my little home mentioned in somebody’s comment, even if because of dire reasons.

Regarding the tale (and the whole book), I cannot get past one reaction: “Whaaaaaaat??!!!”

Celebrinnen @@@@@ 12 – whenever I hear Estonia mentioned, I think of you. I do not know anyone else from there! You are definitely our resident Estonian. :D

…as to the rest of the tale, I have certainly not read this version. It sounds possibly too disturbing for my tastes!! Although Mari, your comments made me laugh out loud multiple times. Thanks for that!!

Ok, now I’m digressing from the topic, sorry for that, but Sonofthunder @13 – AWWWWW … That just filled my little heart with joy :)

9: got to disagree there. The idea of a contract between ruler and ruled, with the ruled being the right of rebellion if the ruler let’ them down… that is the direct opposite of Tory Jacobitism. Divine Right, remember? The king wasn’t the rightful king because he did a good job, any more than your son gets to be your son because you love him; he is the rightful king because he is anointed by God and that’s why he’s a good king.

The weirdness of this tale reminded me of a sort of unofficial sequel to Gulliver’s Travels I found and read at the library at Ball State when I was a student there in the 80’s. It was not written by Swift and really bizarre. It started with Gulliver living at home despising his fellow humans and only enjoying the company of his horses, but it sent him on a ship voyage, with horses. The horses died and immediately Gulliver begins acting like a normal human again and never gives another thought to his cherished friends. The ship ends up in some strange new land which Gulliver explores WITH the entire crew of the ship going everywhere with him! There is one bit I recall in which the leader of a village the crowd is visiting entertains them with a flute, the music from which causes the women who hear it to disrobe and dance naked for them. When the music ends they awake to find themselves naked in front of this big crowd of sailors and rush away in great confusion and embarrassment. The story as a whole rambled, was really boring to drag through, and didn’t seem to give a darn about previous chapters’ events. Must be a common problem in popular literature of the time.

I just wanted to say thank you Mari Ness. This post was really funny. Yes. Really. That’s all I have to add to the conversation. I know the lack of substance in my comment might upset some, but if so you can turn into a toad and crawl into the basement.

Well firstly, Divine Right only applies to the monarchy – that’s kind of the point. The early Whigs were all about the idea that the right to rule of the wealthiest Protestant landowners trumped that of the King: Jacobitism was about answering that position with “Nuh-uh”.

When rebels throughout history have managed to convince themselves that monarchs who were actually in power were on their side against the nobility, it’s hardly a stretch to suggest that some could have believed it of a king over the water, when by definition there would be far less evidence to the contrary. There’s also a difference between what’s compatible with the theory behind supporting the Stuart monarchy in 1642 or 1688, and what’s compatible with the thoughts and feelings of people who missed it in 1745.

This is where the Confederate comparison falls down: the Confederates were hegemons defending the status quo, from which every white individual personally benefited at the expense of the enslaved population. Even in 1688, the average Stuart soldier wasn’t defending their own privilege. (Indeed, every Catholic among them was defending their recently gained freedom from vicious persecution.)

From Caribbean pirates at the start of the Hanoverian era, to Robert Burns when the rebellion was still a living memory, plenty of people DID freely mix Jacobite and radically egalitarian rhetoric in the eighteenth century. Sure, this wasn’t very consistent with what their cause was supposed to be about, but that’s not the issue here, since the question at hand is whether a malcontent like Merryman could have had Jacobite sympathies.

There were different Jacobites, and different Jacobite supporters, fellow travellers and sneaking regarders. Almost any combination of beliefs could lead either to supporting the ’15 or the ’45, or opposing them, depending on the logic employed.

This also means it’s tricky to bundle up the disgruntled “Dick Merryman”‘s complaints and guess which side he sympathised with.

Leaving aside contemporary politics, I do feel for him on the question of traditional Christmas; he’s defending a model literally thousands of years older than Christianity in Britain. We’ve found pig bones at Stonehenge–of a pig age consistent with mass slaughter at the winter solstice–dating c.2,500BC, meaning large numbers of Neolithic farming people came together from the surrounding countryside to have a big feast organised by the local chief, who would have pinned his prestige on being the provider of the goodies.

Dickens still remembers this more communal, boss-based pre-nuclear-family Christmas as “Christmas Past” in A Christmas Carol (compare with Bob Cratchit and his family at home in Christmas Present)

So, Jack’s granny has a “magic bean” eh? One wonders if it resides at the prow of a “little boat!”

Why is dis not for kids. Because I am a kid and didn’t know why this is not for kids