I’m smelling mulled cider on the stove, seeing mistletoe in the entryway, and hearing carols carried upon the wind. It’s Christmas time, so let’s talk about some of the origins behind my favorite holiday.

I know, I know. The holiday is about the birth of Jesus. And sure enough, “Cristes maesse” is first recorded in English in 1038 for “Christ’s Mass,” the mass held to honor of the birth of Jesus. “He’s the reason for the season,” as the church signs often say.

Except … maybe not this season. The Bible doesn’t give any actual date for the birth of Jesus. About the only biblical clue we have about the date is that, according to Luke 2:8, the shepherds were still residing in the field. Not much to go on, though our earliest recorded dates for the birth of Christ fall in line with more likely times for shepherds to be in the field. Clement of Alexandria (153-217), for instance, dates the birth to November 17, perhaps in part due to the shepherding detail.

By far the most popular early date for Christ’s birth, though, was March 25, which was held by Tertullian (155-240) and Hippolytus of Rome (170-240), among others. On the Julian calendar, this was the date of the Spring Equinox, and it was therefore generally believed to be the date of Creation. For their part, early Christians further tied the date to the Passion of Christ, who was perceived to be a “new Adam” whose death effectively restored Creation to proper order. So Jesus, by their logic, must have died on March 25. As it happens, it was a long-standing Jewish tradition that the great figures of history were born and died on the same date. The Bible says Moses lived for 120 years (Deuteronomy 34:7)—not 120 years and three months or some such—so folks figured Moses must have lived exactly 120 years. The same, it was thought, must be true of Jesus. So if he died as the new Adam on March 25, he must have been born on that day, too.

In 243, the anonymous author of De Pascha Computus (On the Dating of the Paschal Feast) went one step further with this Genesis allegory: If Creation began on March 25, he argues, Christ must have been born on March 28, the date on which God would have created the sun—since Jesus was perceived to be the light of righteousness.

The December 25 date first appears in the writings of Sextus Julius Africanus (160-240). (Some folks will cite earlier passages attributed to Theophilus of Caesarea and the aforementioned Hippolytus that have the date, but textual scholarship has revealed these to be later interpolations.) Africanus believed that Christ’s conception, not his birth, was the moment of reckoning for Creation, so he dated the conception to March 25 and the birth to exactly nine months later, December 25. This new date had its own symbolism: the birth would now fall in line with the Winter Solstice, the day of the least amount of daylight (at the time December 25 on the Julian calendar). From that point forward, the sun (i.e. the sun, God as light) would grow, just as Jesus did. Allegory for the win!

Alas, Africanus didn’t carry the day early on. March 25 remained the dominant date for quite some time. It wasn’t until the fourth century, in fact, that Christmas clearly exists as an established feast date for December 25, first appearing in the Chronography of 354.

What happened to bring on the shift is hard to say, but scholars strongly suspect it was an amalgamation of forces related to Christianity becoming an official religion of the Roman Empire earlier in the century. When this happened, when Christianity was able to move from defensive questions of survival to offensive questions of rapid expansion, decisions seem to have been made to align the Christian story with existing pagan traditions in order to more easily assimilate new converts. As Pope Gregory I put it in a letter to Abbot Mellitus as he sallied forth on a missionary effort to convert the pagans of Anglo-Saxon England in 601: the missionaries should appropriate pagan practices and places of worship whenever possible, because “there is no doubt that it is impossible to cut off everything at once from their rude natures; because he who endeavours to ascend to the highest place rises by degrees or steps, and not by leaps.”

To get back to the 4th century, Rome had some pre-existing holidays at the end of December. Leading up to the Winter Solstice on December 25 (on the Julian calendar, remember) was Saturnalia, a period from December 17-23 honoring the Roman God Saturn that represented a joyous festival of raucous fun and gift-giving in which Roman society was turned upside-down. In addition, December 25, for obvious reasons, was the feast day for the popular cult of Sol Invictus (the Unconquered Sun), which was brought to Rome with the accession of Emperor Elagabalus in 218 and made the primary religion of Rome during the 270-274 reign of Emperor Aurelian.

Adopting December 25 as the date of Christ’s birth therefore built upon (and simultaneously undermined) existing Roman holidays. Add in the allegories of Africanus that were making a comeback in the fourth century, and it was settled. By the end of the fourth century the alternative dates for the birth of Jesus had largely been abandoned across the Empire, and the Mass of Christ—Christ’s Mass, i.e. Christmas—was given on December 25. As Christianity spread onward, this same kind of syncretism brought in Germanic Yule, which was originally celebrated from late December to early January before eventually falling into place on the same date.

Thus by twists and turns we get to our now “traditional” dating of Christmas on December 25.

Whew.

If we went back in time we would hardly recognized the holiday, though. It was a solemn occasion quite different from the merriment we enjoy today. And it wasn’t a big deal, even after it got a boost with the Christmas coronation of Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor in the year 800. Christianity dominated the Roman Empire, but it would be a mistake to imagine Christmas as dominating the Christian landscape in the way it does today. Something recognizable as Christmas—large displays of gift-giving and merry parties—doesn’t really appear until the 19th century, largely due to the popularity of the poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (you might know it as “’Twas the Night Before Christmas”). For most of its existence, the Christian calendar has been wholly built around Easter, which was the holiday of holidays for Christians.

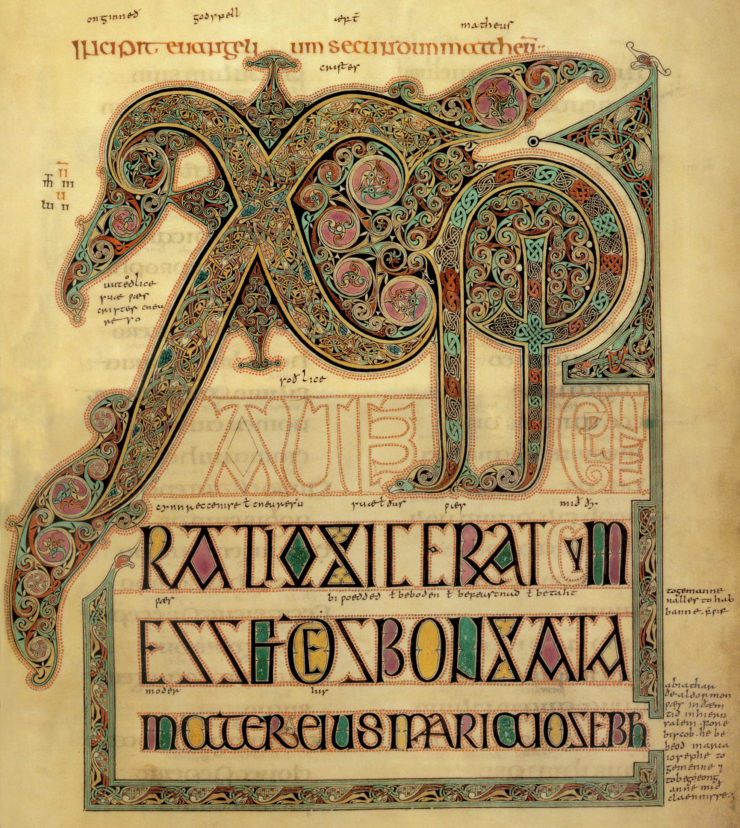

Speaking of medieval traditions, that’s where the abbreviation “Xmas” comes from: the “X” is the Greek letter chi, which is the first letter in the Greek spelling of Christ, Χριστός. Due to the deification of Christ amid Trinitarian Christians, Christ was synonymous with God. Like Jews who refused to fully write out the name of God by omitting the vowels in the Tetragrammaton, Christians could abbreviate Christ’s name to the chi alone or with the next letter, the rho. Thus we get the chi-rho christogram (☧) that has surely led more than one parishioner to wonder what “px” stands for. It has also led to beautiful Christian artwork. Many medieval manuscripts of the Bible, for instance, devote an entire page of illumination to the first mention of Christ in the gospels (Matthew 1:18). Here, for instance, is the Chi-Rho page of the 7th century Lindisfarne Gospels:

This shorthand for Christ was popularized, too, because for scribes it saved precious space in their manuscripts, which eventually left us with abbreviations like “Xn” for Christian, “Xty” for Christianity, and, yes, “Xmas” for Christmas. So to those wanting to claim it’s taking the Christ out of Christmas, I say it’s time to put an end to the war on “Xmas.”

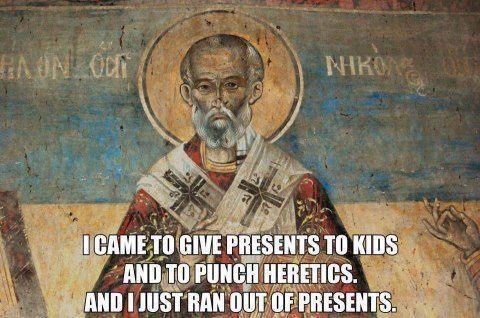

Speaking of violence … You probably already know that jolly old Saint Nick is Saint Nicholas of Myra (270-343), a bishop who became associated with Christmas largely because his Feast Day was held on 6 December and the stories of his secret gift-giving to charity were a great way for the church to deal with Christians who continued to keep alive the gift-giving of Saturnalia even after Christianity had all but stamped out the pagan beliefs behind it. His other claim to fame, though? He was a devout Trinitarian Christian, and it’s said that at the Council of Nicaea he became so angry at Arius, a leader of the Subordinationist Christians (who claimed that Jesus was subordinate to God), that he punched Arius in the face. Yippee-ki-yay!

So a heretic-punching Bad Santa St. Nicholas (whose face was recently reconstructed!) grew up to become Good Santa Claus… with a few dips through Germanic mythology and the Reformation and then something to do with trees.

But that part of it, I should think, is a story for another year.

Happy Holidays, folks—whatever your reason for the season!

This article was originally published in December 2016 as part of the Medieval Matters series.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Culture at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy trilogy set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven, The Gates of Hell, and The Realms of God, is available from Tor Books.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Culture at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy trilogy set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven, The Gates of Hell, and The Realms of God, is available from Tor Books.