We tamper with time at our peril. A new story in the Mongolian Wizard series.

“But I already have as fine a pistol as is made anywhere,” Ritter said.

“Not any more.” Sir Toby dropped the reluctantly surrendered flintlock, its barrel exquisitely engraved with stags and ivy leaves and its unicorn ivory grips carved with wolf heads, into a desk drawer. Then he handed his subordinate an oddly shaped and brutally unadorned sidearm. “This is called a ‘revolver.’ It wasn’t supposed to be invented for another forty years, but a team of scryers in Covington foresaw it and provided His Majesty’s engineers with blueprints. It loads easily and you can get off five shots, one after the other, without reloading.”

“It hardly sounds gentlemanly.”

“Being a gentleman,” Sir Toby said with some asperity, “is something I am trying to cure you of. Here is a box of percussion cartridges—another gift from our friends to the north. Which is where I’m sending you next. There has been a murder.”

“You suspect sabotage?”

“Sabotage, espionage, sedition, treason, terrorism, incompetence, or happenstance. It must surely fall into one of those categories, unless it turns out to be something else. Finding out which is your job. Now hurry off to the firing range and get in some practice. You’re going to need it.”

Ritter went.

Buckinghamshire, in the early days of the war, was a grey and joyless place. To compound matters, an officer in an unfamiliar uniform who spoke with a pronounced German accent was an object of profound suspicion to the locals. As if their own military forces were incompetent to protect them from solitary invaders from the Mongolian Wizard’s territories! And to top it off, there was the food. Ritter was half-convinced it was what the locals fed to feared outsiders out of spite, and more than a little afraid that it was what they regularly ate themselves.

“You don’t look like you’re enjoying your meal much,” Director MacDonald said. He was a sharp-featured man with lively eyes, whose idea, Ritter gathered, the entire operation had been. He seemed to be a civilian and a Scotsman as well. In Ritter’s opinion, he lacked gravitas.

Ritter looked down at the boiled peas, boiled potatoes, and grey meat on his tin tray. “I assure you, parts of it are quite good.”

MacDonald laughed. “You have a sense of humor! How unexpected.” Then, “I thought that perhaps you were put off by the looks that some of the girls are giving you. It’s only to be expected, you know. Most men with a talent for foresight are routinely attached to intelligence units at the front lines and consequently the ratio of women to men here is ten to one. The majority of them are single and of an age when one normally makes a marriage. So naturally they are interested in a strapping, good-looking fellow such as yourself.”

“I honestly hadn’t noticed,” Ritter lied. Distracted, he pushed the tray away from himself—and knocked it off the table.

From every corner of the room—baronial, high-beamed, and shabby in the way that takes generations of moneyed neglect to accomplish—girls burst into cascades of giggles. Coloring, Ritter realized that they had all paused in their meals to stare at him, waiting for the tray to fall. A canteen worker hurried to clean up the mess and he said, “Tell me about the murder.”

MacDonald turned instantly serious. “Alice Hargreaves was the middle daughter of a dean of Christ Church, Oxford. She was identified as having a latent talent for foresight, recruited, and sent here for training and exploitation. She arrived at the Institute a week ago. The next morning, she was discovered dead.”

“She had no enemies, then?”

“There was no time for her to acquire any. Nor could it have been anything she foresaw, for her talent had yet to be unlocked. Of all the young women in our employ, she was the least likely to be murdered.”

“Perhaps she discovered something—a spy in your operation or suchlike?”

“On her first evening here? Highly unlikely.” MacDonald produced a thin metal rectangle, perhaps three inches long. “Here is what Miss Hargreaves looked like. Lovely, wasn’t she?”

On the object was a monochrome image of a young woman—good looking, dark eyed, serious of expression. “What is this thing?”

“A tintype. One of our less bellicose recoveries from the future. All our staff have their images recorded on arrival.”

Ritter studied the image for a time, returned it, stood. “I will examine the scene of the crime now.”

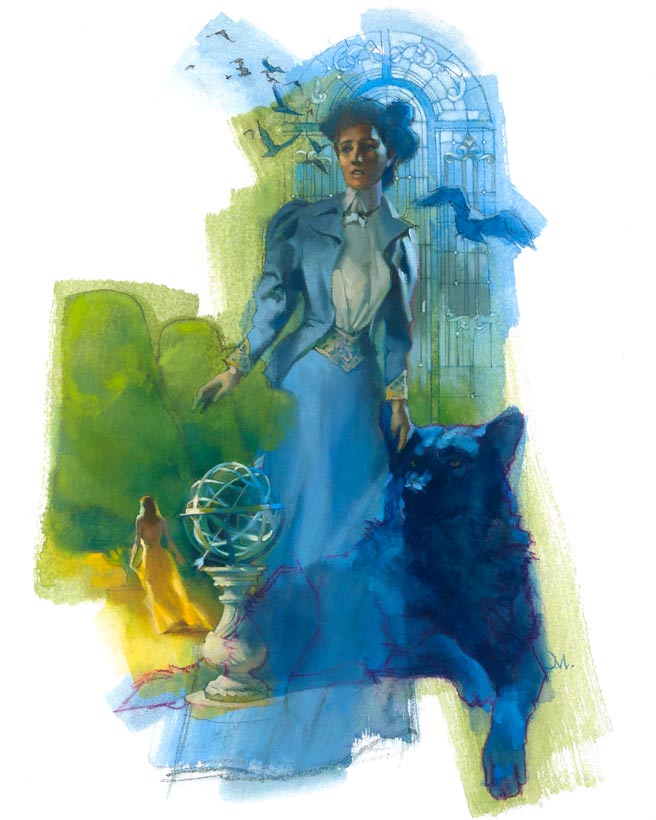

Freki had waited outside the Gothic stone building—originally a monastery, later converted to a mansion, then built over and added to by centuries of wealthy owners encumbered by not one whit of good taste, until the resulting whole resembled a witch-haunted mountain range in some treeless Northern land—while Ritter ate. Now, at a thought, the wolf trotted to his side. Together they followed Director MacDonald through the grounds and downslope to an oversized pond. Nearby was a yew maze, its hedges significantly taller than either man. They all three entered it.

“The maze is left over from more opulent times,” MacDonald observed, “and I should warn you that the young ladies think it’s a romantic spot in which to rendezvous with their beaus. I suggest we keep up a steady line of chatter in order to warn anyone who might be lurking ahead. You have questions, I am certain. This would be a good time to ask them.”

“Tell me about the method of precognition your ladies employ. My father always said that clairvoyance was the least of all magical talents, yet you seem to have disproved his thesis.”

“Doubtless,” MacDonald said, “you think of the future as a country existing in a direction to which you cannot turn your eyes, and of precognitives as being able to peer ahead where you cannot. We look forward, yes—but into a blizzard. The future is always changing. You take extra time to shave one morning and as a result you miss the coach to Bristol and have to wait in London an extra day. So you strike up a conversation with an idler in your club, who tells you of a financial opportunity particularly suited to your talents. Thus you find yourself traveling on business to the Italian Alps, where a chance encounter with a brigand costs you your life. Every man makes such decisions every day and as a result, the future is in constant flux. Those brief islands of stability which people such as I have traditionally been able to glimpse, are rare and very particular to the individual: a vision of one’s future spouse, say, or the moment when one is about to set sail on a ship destined to sink with no survivors.”

“But you changed all that.”

“I did. When I reached adolescence and the talent came upon me, I was equally struck by its weakness and its potential. So I began to experiment. It was my innovation to create those islands of stability by training a precognitive to focus her thought backward toward her earlier self, sitting quietly in that identical same room at a specific time and thinking forward to herself where she would later be. I quickly learned that messages regarding the actions of individuals were wrong as often as not. But transmissions of simple material fact were inerrant. So I have created an institution that passes technological information backward in time for as long as a century, handed from seer to seer, like so many heliograph stations in time.

“I see you carry one of our revolvers. Its design is something that we can confidently expect will not change between now and the moment one of our ladies sits down to sketch its workings for her younger self to read. Hence, its existence today, a hundred years before its invention.”

“You dizzy me, sir.”

“I intend to dizzy the world. Ah! Here we are. This is where Miss Hargreaves’ body was found.”

Ritter looked about him. The center of the maze was the center of a maze. The hedges were hedges. The grass was grass. There was a bronze sundial with the motto Tempus Vincet Omnia. “How was she killed?”

“With a rock to the back of the head.”

“You have it still?”

“Good lord, no! That would be morbid. It was promptly thrown into the pond as soon as the corpse was removed.”

“Pity. Sir Toby has some excellent forensic wizards we could have called upon.” Ritter sent Freki nosing about the grass. “Could it have been a crime of passion?”

“We brought in a hedge-witch specializing in midwifery. She verified that the corpse was still virgin. It had not been molested either before or after death.”

“Was she able to establish the time of death?”

“Midnight, or slightly thereafter.”

The wolf picked up faint traces of human blood, the faded scents of many visitors, and nothing else of any interest. “There have been a lot of people through here.”

“As I said, it is a popular place for lovers to meet.”

“I will speak to the victim’s roommate now.”

“Don’t speak to me!” Margaret Andrewes scowled down at a sheet of paper covered with mathematical formulae for a very long time. Occasionally she glanced up at the wall, where hung a hand-drawn pasteboard chart showing thick colored lines that flowed in and out of one another. Finally, she turned over the sheet and, looking up, said, “I know why you’re here. Ask me what you will. I know nothing that will be of any use to you.”

“You foresaw that, did you?”

“No, of course not.” Andrewes’ eyes darted away from him but her voice was firm. “I met the girl only the once. We had dinner together in the commissary and then she went out for a walk and never came back. I was weary and went to sleep early that night. In the morning I saw that her bed had not been slept in. That was the first I knew that something was wrong. I notified Director MacDonald’s secretary, Miss Christensen, the grounds were searched, and her body was found. That’s all.”

“What did you talk about?”

“Where she could put her things. How to acquire a permanent meal card. Nothing personal, I’m afraid.”

The office in which the interview was held was small, tidy, and without personality. The door to the back room (created, Ritter saw, by the addition of a wall halfway down the original space) was slightly ajar, revealing a bunk bed. The lower mattress was covered by a bright quilt. The upper one was empty.

“I thank you for your cooperation, Miss Andrewes,” Ritter said at last. “We shall take our leave.” They stepped outside and down a long hallway of rooms, all small, each housing a pair of precognitives.

Miss Andrewes had not looked at the director once. That meant something. Exactly what, Ritter had no idea, but he knew that it was significant. When they were out of earshot, he commented, “That was a striking woman.”

“She can be quite likeable under ordinary circumstances.” Almost to himself, the director added, “A trifle plump, mind you. But pleasantly so.”

“Excuse me, sir.” A lean, older woman, slight of profile and disapproving of mien, handed Director MacDonald a sheet of paper. “This just came in.”

“Thank you, Miss Christensen.” The director glanced at the sheet, scowled, and said to Ritter, “You must excuse me for a moment. My secretary will look after you in my absence.” He spun on his heel and hurried away.

“The director seems a very busy man,” Ritter commented to the secretary.

“That’s one word for it,” she replied acerbically.

“Forgive me. But I must ask. Where was the director at the time of the murder?”

“He and I were both with Peter Fischer who, despite his gender, is our best scryer. Also, rather a hothouse flower. He was having one of his periodic crises of confidence, and it took quite a long time to calm him down. We were with him from ten in the evening until at least two in the morning.” Miss Christensen smiled coldly. “Director MacDonald, I assure you, is no more your murderer than I am.”

That evening, Ritter went over all he had learned—or, rather, failed to learn.

There were not many people who had had contact with Miss Hargreaves—the ostler who had stabled her horse and directed her to Director MacDonald’s office, Miss Christensen who in the director’s absence had given her the standard orientation for a newcomer, the technician who had recorded her image on tintype as part of that orientation and, of course, her roommate for less than a day Miss Andrewes. Ritter had interviewed all of them, with the same results: She was an intelligent and attractive young woman who made no particular impression on anybody before slipping into the yew maze and getting herself murdered.

Ritter had been given an attic room which had been a servant’s quarters when the building was a mansion and only God and the Cistercians knew what before then. So far as he could tell, the stairway served no other occupied rooms. There he sat that evening with his shoes off and a small fire in the hearth to ward off the spring chill, trying to sort out the facts, such as they were. Ritter found himself unable to form any theories or discern any pattern to the events surrounding the death. The strangeness of the Institute’s purpose kept getting in the way.

Very well, then, he must consider that strangeness.

What had he learned?

And what did it mean?

That the future existed, somewhere up ahead of him. That it could be changed. Which implied that there were more futures than one. Which made no sense. There was only one past and it was inalterable. Why should the future be any different?

If the future was mutable, then what about the present? Did it solidify underfoot the instant one arrived at it, like the solidity of land gathering itself beneath the feet of a castaway when he finally manages to struggle free of the sea? Or was it, too, uncertain? Ritter suspected that . . .

A flutter of wings filled the room and a frantic bird flew past Ritter’s ear.

He started to his feet and felt the brush of feathers against his cheek as the panicked creature sped back the way it had come. There was for it no exit, but the creature had no way of knowing that. It looped through the room in wild, angular ambits.

Wherever could it have come from?

It must have flown down the chimney earlier in the day and been hiding in an obscured corner of the room when he lit the fire. There was no other possible explanation.

The beating of wings ceased.

Ritter looked around.

The bird was completely gone.

Which—in a room so small, with door closed and the single window sealed shut by multiple layers of old paint—was impossible.

Ritter’s thoughts were interrupted by a low whine. Freki was crouched low against the ground, fur abristle. Gently, he touched the wolf’s mind and was astonished to discover fear. Simultaneously, outside his door he heard steady, heavy footsteps coming up the stairs.

The footsteps reached the top landing and continued along the hall. They stopped in front of his door.

And then . . . nothing.

Ritter drew his revolver and silently positioned himself to the side of the door. Then he twisted the knob and flung open the door, mentally prepared for anything.

But there was no one there.

After such a baffling non-event, there was no chance of sleep. So Ritter banked the fire, pulled on his boots, and took Freki out for a walk. A grey, ghostly light flooded the grounds, cast by a full moon overhead. The great house and all the wooden sheds and houses about it were silent and dark. Moved by nothing more definite than whim and Brownian motion, he found himself at the mouth of the yew maze. He entered it and made his way to its center.

The pale figure of a young woman turned eagerly at his approach and started forward. Then, on seeing his face, she flinched away from him. “Oh!” she said. “You startled me.”

Freki, who had been lagging behind, now padded up to Ritter’s side. For a second time, the young lady started. Then she recovered herself. “What a state I’m in! I thought for a moment your dog was a wolf.”

“Oh, he is a wolf, indeed. But he is a very gentle and polite wolf. Freki, show the lady what a gentleman you are.” Slipping into his animal’s mind, Ritter made him sit up like a dog and offer his paw. Laughing, the young woman shook it vigorously, saying, “I am very pleased to meet you, Freki.”

Ritter moved the wolf back to his side and disengaged from his thoughts. Then he said, “Should I leave? Are you meeting someone?”

Even in the moonlight, he could see her blush. “Forgive me, please. Yes, I am waiting for Curdie, and . . . well, tonight is special. I have never met him before, you see. But I had a vision, and–”

“I understand.” Ritter clicked his heels together and bowed. “I shall leave immediately. It has been very pleasant meeting you, Fraulein . . . ?”

“Hargreaves,” she said. “Alice Hargreaves.”

Ritter felt a cold chill. “But surely . . .” he began.

The universe shuddered, and the woman ceased to be.

Ritter spent the better part of an hour hidden in the shadows of a copse of trees, waiting to see if someone would approach the yew maze. But no one did.

Finally, there was nothing to be done but to go to bed.

In the morning, he resumed his investigation.

First, he joined Miss Christensen in the canteen at the small table where, it was evident, she habitually ate alone. With dour grace, she accepted Ritter’s self-invitation to sit. Then, after the requisite small talk, Ritter said, “Tell me. Is the director having an affair with Miss Andrewes?”

Miss Christensen put down her cup of tea. “I really couldn’t say.”

“I remind you that there has been a murder. This is no time for false reticence.”

“You don’t understand.” The secretary raised her chin and turned her aquiline profile to either side before lowering her voice to say, “The young ladies here are informally referred to as the director’s harem. I long ago gave up keeping track of which one he was currently involved with.”

“So conceivably, Miss Hargreaves could have learned of this affair . . .”

“If she did, and if there were any such affair to begin with, it would scarcely be cause for murder. The director’s dalliances are far from secret—ask any of the other girls, and they’ll tell you.”

“Very well,” Ritter said. “I shall.”

Miss Andrewes’ rooms were at the end of a long, wood-paneled hall in the labyrinthine Women’s Wing, culminating in a small chapel which had been converted into a spacious janitorial closet. Thus, she shared a wall with but a single suite.

That suite – a front office with twin desks and a birdcage containing three fairies which sang in voices like little silver bells, and a bunk bed in the back room—was shared by two young women, twin sisters as it happened, named Lily and Rosie. After a certain amount of giggling and blushing, they were happy to confirm Ritter’s suspicions. Director MacDonald and his prize scryer—everyone agreed she was particularly good at her job – were indeed romantically involved. In fact, once begun, the sisters grew so explicit in their details of what had been overheard through the common wall that at length Ritter flushed and had to beg them to stop. “And Miss Andrewes’ character?” he asked, to cover his embarrassment. “How would you describe her?”

“Very definite,” said Rosie. “She’s top-notch as a seer, nobody could claim otherwise. But . . .”

“. . . but a little stuck-up,” Lily finished for her. “As if she were a fairy tale princess.”

“One who had her destiny foretold at birth, so she knew she was entitled to great things.”

“Still, a good scryer,” Lily said. “Very disciplined. Very strong.”

“The best in the Institute, would you say?”

“Oh, no. That would be Peter Fischer. He’s really quite astonishing.”

“I imagine he’s rather sought-after then,” Ritter said, thinking of the ten-to-one ratio of women to men that Director MacDonald had mentioned.

The sisters burst into laugher again. “Dismal Peter Fischer? Popular?” Lily cried.

“Imagine kissing Mr. Gloomypants!” Rosie gasped.

Which told Ritter whom he must interview next.

“So here you are at last,” Peter Fischer said. He did not stand. Ritter had expected a melancholic. He found a man in the grips of despair. Fischer’s manner was dark and he would not meet Ritter’s eyes. “You have questions. Go ahead and ask. I must caution you that I am bound by the Official Secrets Act and there are some matters I cannot disclose.”

Ritter took a chair. “I will start with what I hope is not a delicate topic for you. I was told that most males with foresight were sent to the front. Yet here you are.”

“I had visions. Or nightmares, rather. Of unspeakable things that would happen if I went there. Normally, such premonitions would not be taken into account. But what I saw was . . . I had to be sedated. Even today, there is a doctor who checks in on me regularly and sometimes administers an opiate. I . . . I am afraid that is all I am at liberty to tell you.”

“I understand.” Ritter looked about the office. Save for Director MacDonald’s, it was the largest he had seen so far, and by far the most cluttered. There were drawings and charts tacked up everywhere on the walls. Some had been turned blank side out. “Similarly, there are certain of your technical drawings I am not allowed to see?”

“Yes. It is nothing personal.”

Ritter pointed. “That chart with the colored lines. I have seen it or something very like it in every office I have visited so far. May I ask its purpose?”

“A trot sheet of variable timelines. It is updated daily. To our prior selves, we are only a statistical possibility, you see. So when we are projecting messages into the past, we must visualize their passage along variant gradients of likenesses.”

“I don’t quite follow you.”

“Marcus Aurelius said, ‘Time is like a river made up of the events which happen, and a violent stream; for as soon as a thing has been seen, it is carried away, and another comes in its place, and this will be carried away too.’ Heraclitus observed, ‘You cannot step twice into the same stream. For as you are stepping in, other waters are ever flowing on to you.’ And Cratylus rejoined that one cannot step in the same river even once. When I was in university, these were merely interesting speculations. Since, Director MacDonald has proved—and experience confirmed—them all to be observable facts.” Then, possibly realizing how difficult this must be for his auditor to follow, Fischer sighed and said, “Think of it as a chart of river currents.”

“But if what you say is true,” Ritter objected, “then not only is the future variable, but the past as well.”

Almost pedantically (Ritter had the impression that the young man found a refuge in abstractions from a world he otherwise found unbearable), Peter Fischer said, “There are two chief theories explaining the structure of time. One states that whenever a decision is made, however small, all possible outcomes occur simultaneously. Thus, if a coin is tossed, the act creates two universes—one in which it came down heads and another in which it came down tails. So that even the most humdrum of men must necessarily be constantly creating new universes and the bustling happenstance of daily life is responsible for a burgeoning infinity of worlds.”

“That seems wasteful,” Ritter observed.

“Extravagantly so,” Fischer agreed. “All that energy, and for what? From where? No, I subscribe to the ‘branching timelines’ theory. Which posits that while temporary universes branch outward, only the central trunk is stable. Deviances from it which make no serious difference merge quickly back into it. This is why two people will often have variant memories of minor events. Lines which cannot be reconciled simply dwindle to nothing. Significant ruptures, however—well, nobody knows.”

Ritter tried, with little success, to comprehend this vision of time. “Surely there must be other theories?”

One pale hand rose in a listless gesture of dismissal. “As many as there are possible universes. It may be that all of them are true. Or none. All we know for sure is that time is fluid and that we can nevertheless work within that fluidity.”

“One last question. Could I prevail upon you to look into the future—or, rather, send a message back from it—and tell me the results of my investigation? It would save me a great deal of time and trouble.”

Fischer did not look up. “I . . . no. That is not permitted, you see. I . . . have been sworn not to do so.”

Putting his hands on the arms of his chair preparatory to getting up, Ritter said, “I want to thank you for–”

Abruptly, he found himself standing before the sundial at the center of the yew maze. Opposite him was Peter Fischer. The young man looked directly at Ritter, tears streaming down his face. “From earliest adolescence, I knew she would be my wife. My very first vision was of Alice Hargreaves. And now . . .”

“Who killed her?” Ritter heard himself say. “Was it the director?”

“Director MacDonald? He is nothing more than an opportunist and a mouse hunter. Their affair would have soon ended and then I could surely have convinced Alice my love was true. But I was jealous and wrote back to myself to delay the director so he would not meet her in the maze. I did not know my folly would result in her death.”

“Can you not contact yourself in the past and–?”

“Do you think I haven’t tried?” Fischer cried. “The currents about the time of her death are so turbulent that nothing gets through. Perhaps it is just as well. There are worse things that could happen than–”

The world jolted to one side.

“So here you are at last,” Peter Fischer said. They were in his office again. “You have questions. Go ahead and ask. I must caution you that I am bound by the Official Secrets Act and there are some matters I cannot disclose.”

“Act or no, you will answer my questions,” Ritter said harshly. “Begin by telling me what could possibly be worse than the death of the woman you loved.”

Margaret Andrewes shrieked when Ritter burst into her office and objected noisily when he seized her arm and hauled her up from her desk. But she allowed herself to be marched to the director’s office readily enough. A man with a wolf was not easily disobeyed. Pushing past Miss Christensen, he slammed open the door to the inner sanctum.

Director MacDonald came to his feet scowling with displeasure. Then, seeing that his lover had been hauled before him, he sighed in exasperation. “Please. I can guess what you’re about to say. But Miss Andrewes and I are both adults and what we do in our free time is no concern of yours.”

Ritter released Margaret Andrewes and kicked the door shut behind him. “I spoke with Miss Hargreaves last night. Don’t pretend you don’t know such a thing is possible. All your meddling in causality, altering the past as well as the future, creates disturbances in time. People and things are displaced from their proper locations in the scheme of things. A bird flying over a sunlit meadow finds itself in a garret room at midnight. A young woman waiting at the center of a maze to meet her lover for the first time is thrown forward a week, where she tells me his name is Curdie.

“That was your childhood nickname, wasn’t it, director? Or perhaps it was what you were called at public school. I imagine your paramours employ it as an endearment.”

Tensely, carefully, Director MacDonald said, “I was to meet Miss Hargreaves in the yew maze, yes. But I was delayed and by the time I got there, she was already dead.”

“That is so. It must be terribly convenient for you to take as lovers women who already know the liaison will occur. Unfortunately, those you are about to abandon can see that coming as well. So a woman who had the misfortune of loving you and then being cast aside sent a message back to her earlier self detailing exactly what she must do.”

Ritter addressed Miss Andrewes directly: “Is that not right?”

Margaret Andrewes turned pale, clasped her hands, and did not speak. Director MacDonald looked surprised and then relieved. A little smile played upon his face. “Well,” he said. “I am astonished.”

“I shall leave it to you to call in the local authorities,” Ritter said to the director. With a thought, he called Freki to heel, preparatory to leaving. “When you are done with that, you can start closing down the Institute.”

“What?” For the first time, MacDonald appeared genuinely shocked.

“How many apparitions occur daily here?” Ritter said. “In my brief stay, I have experienced several. You are eroding the very underpinnings of reality. I know you were warned. Master Fischer has told me of the visions he had of the chaos your work will unleash upon the world—visions which, ironically, his posting here is helping to bring about. Right now, the effects are small and almost harmless. But your little phantasms will grow into monsters if you are not stopped.

“So I shall return to London and stop you. Trust me, when I have made my report, you will have to find a new line of work.”

Ritter was staring intensely at the director as he spoke. So he was caught off guard when Miss Andrewes slammed into him, all but knocking him over. Her hands closed about his throat and, with surprising strength, she began choking him.

Even as he struggled to pry the woman’s hands from him, Ritter saw Director MacDonald reach into a drawer and pull out a revolver. Freki’s training, however, was good. Before he could manage a mental command, the wolf had launched himself at the director.

Desperately, and despising himself for doing it, Ritter punched Miss Andrewes hard in the face. She let go and staggered back. Meanwhile, the first bullet from MacDonald’s gun struck Freki. Blood flew.

Ritter snatched his gun free of the holster. He saw Freki’s body hit the director, sending his second shot wild. Miss Andrewes screamed. He leveled his revolver at MacDonald, who was bringing his gun around toward him.

Ritter shot the man three times in the chest.

Simultaneously, Ritter felt his own body lurch backward and to one side. One shoulder went numb. So this was what it felt like to be shot! As he fell toward the floor, he could hear alarmed voices outside the room, the door slamming open, and . . .

. . . and the world shifted again.

Dead calm. Ritter was on his feet, unhurt. Freki sat not far away, fur up, a worried-looking expression on his face. There was nobody but the two in Director MacDonald’s office. There were no bodies nor any indication of the uproar that repeated gunshots could be expected to provoke.

The door flew open and Peter Fischer stood panting within it. “Thank God!” he cried. “It worked.”

Miss Christensen poured tea and then left the office, closing the door behind her.

Director MacDonald took a long sip from his cup and then said, “I don’t know whether to be grateful to Fischer for saving my life or angry at him for blabbing in the first place.” He looked wary and his clothes were travel-stained. “How much do you recall of what occurred?”

“I recall that I killed you.”

“So I understand. Yet here I am. Thanks to the warning that our young melancholic hastily sent to his earlier self.” MacDonald lifted a scone from his plate and took a bite. Shedding crumbs, he said, “I am most damnably hungry. The trip to London and back was not an easy one to make in the little time I was given.”

“Will you be attempting to undo Miss Hargreaves’ murder?”

“Oh, Lord, no. Water under the bridge. Anyway, all this message-passing has already destabilized the area most dreadfully. As it is, I shall have bring in mind-readers to monitor the scryers and make certain this doesn’t happen again. Even at that, it will take weeks for things to settle down.”

“And Margaret Andrewes? What will become of her?”

“Nothing. The war effort needs her.”

“I see.” Ritter looked down at the letter that the director had fetched back from London and found himself rereading it for the fifth time:

My dear, dense lieutenant, it began in familiar cursive. Our mutual friend informs me that you will in all likelihood recommend that the Institute be shut down. Coming from anyone else with your knowledge, I would find this incredible. From you, alas, it is all too plausible. Allow me to remind you of the atrocities you have seen with your own two eyes in Krakow. You know what the Mongolian Wizard is capable of. Imagine a world under his domination.

The enemy can create wizards in numbers that we cannot match. Our only hope lies in the Institute and the technology it makes possible. You are forbidden to stand in its way.

Do nor harass my old school chum Curdie. Come home immediately. I have work for you to do.

It was unsigned.

“You have no doubts as to its authorship?” MacDonald’s bright eyes twinkled and he smiled impishly. “I urged Willoughby-Quirke to sign it, but Tibby said that would not be necessary.”

Ritter touched the letter to a candle. “Sir Toby does not like to put his name on such documents,” he said. “For understandable reasons. I will pack now. If you would call up a carriage to take me back to London, we shall be done with one another forever.”

“You don’t want to stay for supper?”

“No.” Leaving his tea untasted, Ritter stood to go.

In the doorway, he paused. “Have you considered the possibility that your work will do irremediable damage to the world? That it might even destroy it?”

“Of course I have. It is a risk we simply must take.”

Ritter stood on the gravel drive outside Yarrow House, waiting for his carriage. As he did so, a distracted young woman rode out of the twilight on a roan mare. Seeing him, she smiled nervously and drew up her horse.

“Hello,” she said. “My name is Alice Hargreaves.”

“I know who you are,” Ritter replied, “and I am afraid that there is nothing here for you.”

“The Phantom in the Maze” copyright © 2015 by Michael Swanwick

Art copyright © 2015 by Gregory Manchess