Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

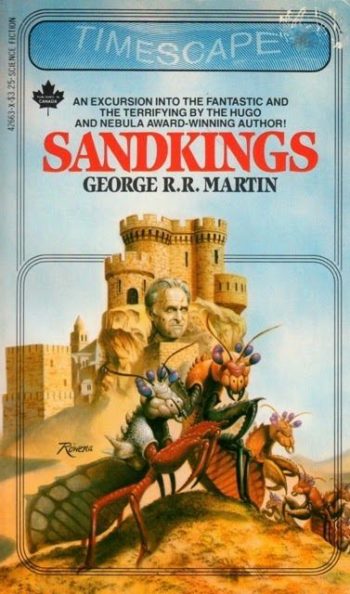

This week, we’re reading George R. R. Martin’s “Sandkings,” first published in the August 1979 issue of Omni. Spoilers ahead.

“I detest cute animals.”

Simon Kress lives in a sprawling manor among the rocky hills fifty kilometers from Asgard, Baldur’s largest city. A connoisseur of exotic life-forms, he’s hunting for a new pet to replace some cannibalistic Earth piranhas. Near Asgard’s spaceport, he discovers a new shop: Wo and Shade, Importers. Jala Wo greets him; Shade doesn’t see customers. After Kress sneers at the usual exotics, Wo asks if he’s ever owned pets who worship him.

The tank at the back of the shop contains a miniature desert. In each corner stands a sand castle: one crumbled, the other three intact. Tiny six-legged, six-eyed, wickedly mandibled creatures swarm among them. Insects, Kress snorts. No, says Wo. A much more complex and intelligent life-form, sharing a psionic hive-mind. They’re called sandkings, and—they war. See the collapsed castle? Its deep-buried “maw” was killed by the other three castle-nations when its mobiles grew too numerous.

The maw eats anything, digests it into pap for the mobiles. Given enough food and space, the mobiles eventually shed their exoskeletons and grow, but they’re safely limited by a closed tank. And look closer: Each castle features a sculpted face. Wo’s face, in fact. She projected a holograph so the sandkings could see the “god” who fed them, and make idols.

Kress is sold. Wo and her four-armed alien workers convert the piranha tank into a sandking habitat housing four maws, lumps of meat with mouths. Mobiles appear aboveground: white, black, red and orange. Each group constructs a castle, fueled by table scraps. Kress watches, fascinated, but he’s disappointed to see no wars. He stops feeding them. Sure enough, they start dragging other-color mobiles to their maws. Kress turns on his holograph face and feeds the sandkings lavishly. The mobiles sculpt his image, a beaming and beneficent god.

He begins throwing parties centered around sandking wars. His friends enjoy betting on the gory spectacles, all but Kress’s ex-lover Cath m’Lane, who storms out. Kress shrugs. Cath has never forgiven him for her puppy, which his pet shambler devoured. Wo comes to one party and chides Kress: Starving sandkings is “artless and degrading.” Better to let them war in their own time—then he’ll witness subtle, complex conflicts!

Kress doesn’t see why a god should be patient. His parties grow gorier when one friend introduces other animals into the battles. Cath reports Kress to the authorities, but Kress bribes them to ignore his infractions. As for Cath, he’ll take care of her.

He stages a sandking battle with a puppy resembling Cath’s lost pet and sends her a recording. Meanwhile the sandkings sculpt new images. These idols depict him as piggish, leering, malevolent, an “idiot god.” Enraged, he grabs a trophy sword, levels the white castle and skewers its maw. The white mobiles collapse but soon revive. One creeps onto his hand; he crushes it, then reseals the tank and gets drunk.

The next morning Cath arrives with a sledgehammer. She attacks the sandking tank, cracking it. Kress, defensive, runs her through with the sword. With dying strength, she breaks open the tank. Sand and sandkings avalanche out. Whites carry off their maw, alive and pulsing.

Kress flees. He scatters poison pellets, preps a canister of illegally strong pesticide. The red and black sandkings are building castles in his garden. The oranges are missing. The whites are down in the cellar, where mobiles drag Cath’s body toward a crude castle. Kress assists by chopping up the unwieldy carcass. What else is a god for?

He provides further sustenance by inviting over the woman who recorded the puppy fight and pushing her down the cellar stairs.

The poison fails to kill the red and black maws. Pesticide spray massacres many mobiles, but survivors drive Kress back inside. He calls Lissandra, a “fixer” he’s employed before. She assures him no euphemisms are necessary, but no, this time his “pest problem” is literal. She brings operatives with flame throwers, lasers, explosives. Two die, dragged down by tunneling mobiles; Lissandra and her last man destroy the red and black castles. But at the basement door a white mobile grown hand-sized attacks Lissandra. She orders her operative to flame the cellar, house be damned. Kress pushes him down the stairs, lasers Lissandra. He was wrong to starve his worshippers. To make amends, he’ll feed them abundantly. As the whites munch fresh bodies, Kress feels contentment not his own—he’s developing a psionic bond with his worshippers.

Buy the Book

The Monster of Elendhaven

His partying friends provide more fodder. Some whites go dormant, swollen and hot. Kress, unable to escape in his (sandking-sabotaged) skimmer, watches a dormant split its exoskeleton and push out tiny hands. The cellar yawns like a throat, breathing. Desperate, Kress calls Wo.

She tells him wounding the white maw must have driven it insane. The mobiles are evolving to suit the environment it perceives. They’ll be bipedal, four-armed, able to manipulate complex machinery—like the workers who set up Kress’s tank. Yes, Shade is an adult sandking, and Kress’s maws were his “sperm,” as it were. But adults aren’t sentimental about small maws; only one in a thousand achieves sapience. She and Shade will help, but Kress must escape on foot, eastward. Flying over the desert, they’ll be able to spot him.

Kress runs waterless for hours. At dusk he spots a house with children playing. He runs to it… before seeing the house is made of sand and the children have four arms and orange skin. They drag him toward a gaping, breathing “door,” but what makes Kress scream at last is their faces.

For they all have his face.

What’s Cyclopean: No purple prose here, only straightforward language to match the straightforward black, orange, red, and white of the sandking hives.

The Degenerate Dutch: Wo appears to be wearing a skullcap, for what are doubtless perfectly innocent reasons that have no relation to stereotypical Jewish cursed-mysterious-store owners. Kress, meanwhile, is awful to his ex-girlfriend, though it’s not clear whether his general misanthropy leaves any room for the more specific disrespect of misogyny.

Mythos Making: Kress seems to be keeping a Shambler From the Stars as a pet; unfortunately he’s starving the poor thing and it ends up consumed instead of consuming. This is the sort of thing that gets you portrayed as a cruel idiot god.

Libronomicon: Kress connects to the library but can’t find any information about his new pets. Maybe he should’ve grabbed a copy of My First Sandking from the corner rack before leaving the pet store.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Stab a maw in the brain-mass, get a mad maw. In both senses of the word.

Anne’s Commentary

I’m a big fan of social insects—your ants, your bees—but as Ms. Wo tells us repeatedly, sandkings are NOT insects. I still think that Rhode Island plays host to the biggest sandking mobile known, which we affectionately (if inaccurately) refer to as Nibbles, the Big Blue Bug. It perches on a garage overlooking I-95, quite motionless, but that’s an insidious sandking trick, isn’t it? At any moment it could summon its sibling mobiles to lurch onto the highway and drag screaming motorists into its maw, which must be enormous, the size perhaps of—well, Rhode Island!

How cool would that be? Provided you were watching from a safe distance, say, the Space Station. Because a maw the size of Rhode Island would be an entity of vast power and intelligence, given what Martin’s mere meat chunks are. It would also be very, very hungry. Good thing there’s a lot of traffic on I-95.

As its introduction in the Foundations of Fear anthology points out, “Sandkings” is “both a literal and a psychological monster story, a social allegory and a moral one.” Taken straight up, it’s sure to make anyone’s skin crawl—bugophobes better make appointments with their mental health care providers before reading. Post your “eww, eww” reactions; you can go multiple interpretive directions—so multiple I really don’t know where to start. That’s the mark of a damn good story, and one, I think, our Howard would have loved.

All right, start with protagonist Simon Kress. Martin makes dry, dark jabs at him from paragraph one: After noting that Kress’s piranhas eat each other when he isn’t around to feed them, he adds that this amuses Kress. A couple paragraphs down, Kress doesn’t like to entertain his friends with exotic pets; he likes to impress them. His first interaction with Jala Wo is arrogant, a demand to know whether she’s “only sales help.” When he forces his sandkings to fight by starving them, he’s “delighted” to witness some carnage at last and “congratulate[s] himself on his genius.” What a supercilious dick. We never learn what Kress’s business is, but I imagine him as a restaurant or movie or art critic supplying reviews to only the toniest intergalactic publications, each one dripping with exquisite venom. In the golden age of Hollywood, he’d have been played by George Sanders—think Addison DeWitt of All About Eve, only with a joystick rather than a cigarette dangling from his perfectly manicured fingertips. All this before he even starts feeding “excessively cute” puppies to his new pets. Oh, and murdering people by semi-accident and/or premeditation. And it’s later implied he’s murdered people before, secondhand, via fixer Lissandra.

Whenever there’s a protagonist to be done away with by monsters, the writer can go two broad routes: Either she can harrow up the reader’s feelings with a sympathetic character or she can set the reader up to cheer when the jerk goes down—down the monster’s throat, that is. Or at least the monster’s lair-tunnel, which, in “Sandkings,” may virtually be its throat! That said, I’m not sure that Kress ends up eaten. He remains the Sandkings’ deity, and though the oranges took off before Kress began exterminating his pets, they received enough of his cruelty to sculpt him as an idol of “brutal mouth and mindless eyes.” If the orange maw has fetched Kress so he may still be worshipped, that worship may take a particularly torturous form.

“Pet” sandkings (as opposed to “free” sandkings like Shade, I’m supposing) adapt to their environments; as pets, they exist in environments created and run by their owners, whom they perceive as gods. Fertile comparison can be made to Klein’s “Nadelman’s God.” With youthful cynicism Nadelman imagines a god of garbage, idiotic and sadistic. His “fan” Huntoon takes up the idea and sculpts the idiot god, from garbage, which is too readily available in his environment. It’s said we make gods in our own images. Then, if we strive to be “godly,” we try ourselves to live up to the self-created idol. Is this argument getting convoluted yet? Good, because isn’t that its nature?

Whatever sandkings are by nature on their planet of origin, in captivity they’re profoundly shaped by nurture. They make sense of their situation by attributing it to a deity, benign or malignant, and then they mold not only their castle-idols after that god, but themselves. Kress’s sandkings grow from insectile to humanoid form, and they wear his face. Even the oranges, most distant from him. Think what the whites will become, who were closest to him, experienced his worst behavior, and had their hive-mind rendered insane by his attack.

Or don’t think about it if you find theology a scary subject, as many writers of the weird do, and Martin here for certain.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

It’s a mark of Martin’s skill that he can turn out a by-the-numbers mysterious-shoppe/bad-man-eaten-by-a-grue novelette, and I’ll read all the way to the end without stopping once to check how many pages are left. And this after I accidentally started reading “Nightflyers”—sorry, neo-compound single-word titles all look alike to me—with its far more appealing deep time and legend-of-legends tropes, first.

So what gets me through my least favorite trope, at novelette length, without it feeling like a slog? For that matter, how does the story of an asshole getting what’s coming to him pull in a Nebula and a Hugo? It’s certainly not Kress, whose name I had to check because I’d already forgotten it since this morning. Sociopaths may be charismatic, but they’re fundamentally boring—which is why in the usual run of these stories I end up flipping pages to see how long it’ll take for them to get et.

Part of it is the Mysterious Shoppe, a trope I do enjoy in spite of myself. This one, like all too many, has a Jewish proprietor—or at least, Kress makes a point of mentioning Wo’s “strange little cap that rested well back on her head,” which sure sounds like a yarmulke to me. This is even less reasonable in late 70s space opera than 1840s gothic fluff, but I still want to know how a nice Jewish girl gets one of these franchises.

But most of it is Wo’s partner Shade—and the worldbuilding intricacies of their reproductive strategy. From the perspective of a childrearing-focused, k-strategy breeding species like humanity, alternate kid-production methods are ripe for horror. Species like Shade’s, which go for numbers rather than focused investment in a few offspring, might do anything from eat their excess babies to… foisting them off on random rich assholes as a source of narcissistic amusement. So Wo explains to a panicking Kress—nothing wrong with selling your parasapient pre-babies, and if something goes drastically wrong, well, the emptor should have caveated.

Except… Wo’s explanation makes no sense. She, and presumably Shade, knew exactly what kind of man Kress was when they sold him the baby sandkings. If a guy tells you he feeds kittens to shamblers, the odds of him doing something horrible and violent to whatever you sell him are high. Yet it’s after he mentions these sadistic behaviors that she makes a pitch perfectly tailored to his narcissism, from the offer of worship to the masculine relabeling of the maws as “kings.” Nor does she provide the sort of detailed how-to manual that you’d get with, say, your first ferret.

And that very specific adaptation of worshipping/reviling their caretakers—hardly a useful adaptation for something that normally comes to maturity “in the wild.”

This doesn’t sound to me like a salmon-ish strategy of laying a million eggs and waiting for ten spawn to make it to the ocean. This sounds more like a cuckoo. Or even more aptly, an Audrey II. Find some greedy bastard, flatter or goad him with his own face, and get him to feed you until you’re old enough to fend for yourself.

Must be blood. Must be fresh.

And then, presumably, Shade can pick up their kids, and pass their successful shoppe-keeping strategies on to the next generation. [ETA: I also just realized this whole thing is maybe a satire of Sturgeon’s classic “Microcosmic God,” one in which the deific human actually gets what he deserves. So that’s another plus.]

Your hostesses have been poring over Foundations of Fear, a worthy predecessor to The Weird edited by the late, much-lamented David Hartwell. Join us next week for one of his deep cuts, Madeline Yale Wynne’s “The Little Room.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.