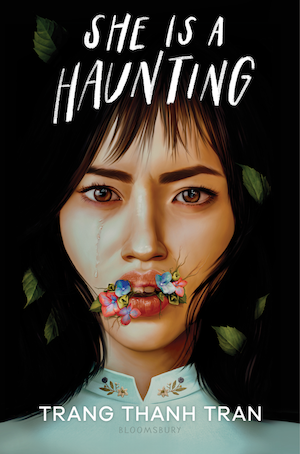

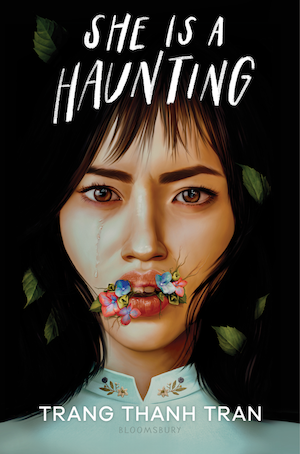

“This house eats and is eaten,” begins Trang Thanh Tran’s debut gothic horror novel She Is A Haunting. The book opens with Jade, a closeted Vietnamese American girl who reluctantly travels to Vietnam for the first time to spend the summer in the colonial house her estranged father is renovating as a B&B–only to find that the house has other ideas.

[Minor spoilers for She Is A Haunting]

Along with refurbishments, the house is given a new local name: Nhà Hoa, Flower House. Ba wants to make it their new family home, replanting roots in the country he had to leave as a child. Yet Nhà Hoa’s dark past is still lurking in the too-fertile flowers, the relics of the missing sixth bedroom, Ba’s nostalgic white business partners, and the looming portrait of Marion Dupont, original madam of the house–mistress to Jade’s great-grandmother, who worked in the house as a child.

Jade believes that the house isn’t quite right, but Ba is only convinced she’s trying to ruin their new life. He cooks Vietnamese dishes for dinner, the way he used to when the Nguyens were still loving and intact. He is sure they can go back to it if they try. Jade is determined to prove otherwise, even as she also yearns for that family too. Ba is manipulating her with the food in several increasingly sinister ways, but it’s also the one thing still tying the family together: the mandatory dinners are the only time the family unites; the kitchen is where conflicts are finally confronted or resolved. Meals remind Jade of warm kitchens on weekends and families that could be. She notes that odd moments like peeling eggs are some of the only times her parents share bits of their families’ pasts. Her mom’s first question on the phone is whether she’s eaten. In the background, unknown relatives laugh over clattering dinner bowls, the family her mother’s finally reunited with.

The first time Ba laughs, he and Jade are cooking together and he tells her how her great-grandmother liked the dish. As they prepare the same food, they exist in the same space for a moment, going through the same ritual side by side. When Jade stresses in this rare pocket of happiness, “It’s always water, sugar, lime, garlic, chilli peppers, and fish sauce, but in what order? What amounts? How do I make it perfect the first time?”—you get the sense she’s not only talking about the food. Despite her anger at her father, she simultaneously remembers the man who smiled at her as he taught her how to loop fishing lines, for dishes he cooked best.

But then one night Jade finds a ghost rooting through the fridge with clammy hands. The dead bride, the Vietnamese wife of a French officer who lived in the house, says Don’t eat.

***

Food in worldbuilding establishes norms, class, agriculture, ecosystem, and mediates interaction; I’ve never quite understood fantasy books that don’t care what their people eat. She Is A Haunting, though, builds itself around its tastes. While Ba is careless in every other way, the preparation of food gets unsettlingly loving attention throughout. This is how you stir the sauce. This is how you descale the fish. This is how you slice mangoes, slice tofu, pluck beansprouts, wrap wontons; how you prepare catfish, snakehead, trout. The family consumes in sensuous detail: crisp crepe with pork belly and shrimp, fish sauce with garlic and sliced chilli, tofu with lemongrass and salt, stewed pineapple slices and flaky fish on warm rice, silken beancurd broken into ginger syrup.

At times, the detail creates tension with what the feast is obscuring. But to me, the meticulousness is often also all the words the Nguyens can’t say to each other.

Buy the Book

She Is a Haunting

Meals have been a stage for Asian families in books across genres, from the plentiful dinners in Fonda Lee’s Green Bone saga to the likes of Crying in H Mart and The Vegetarian . There’s that stereotype about Asian parents: emotionally unavailable, communicating only through bowls of cut fruit and your favourite snacks magically stocked in the fridge, et cetera, et cetera. Even as the secrets threaten to crack the family apart, there’s a father in the kitchen, peeling prawns for dinner, obsessing over the flavours, the ingredients. The things he can navigate so much more easily than a daughter. Even when the supernatural warns you against it, food is family and homeland, and the hunger for that can overpower all else. In this house, you eat connection.

By the time the bride delivers her warning, we’ve already seen Jade swallow several hungers: Wanting to feel at home in her parents’ country. Wanting to get to college and make her parents’ ocean-crossing worth it. Wanting an unbroken family, even as she can’t wait to leave her father behind for good. Wanting girls–specifically, the delinquent coder she ropes into her quest to prove a haunting, with the perfect mouth that threatens to push Jade into a mistake she’s already blown up one life to bury. (The closet is its own particular hunger.) And now, in the most literal sense, she must decide whether to refuse the taste of home based on the whim of a beautiful ghost in her dreams.

In East Asian tradition, death (or in some cases, unjust death) is followed by a perpetual state of hellish hunger. Purgatory is a stomachache, a constant need to be filled. Once a year during the Hungry Ghost Festival, these spirits–ma quỉ in Vietnamese –make their way back to the world and get to feast on the food left by their families, or otherwise the living.

So what does it mean in She Is A Haunting that food brings a broken family together, even if for a surreal moment? What does it mean that Jade is stuck in in-betweens–not Vietnamese enough, not American enough, not straight enough, not openly queer enough, with half a family, without a best friend, plans for the future uncertain, untethered–and all she can do is want and want? And what has the ghost bride seen in this house that when she stands with Jade in the kitchen, it’s instead to tell her not to eat?

If Jade eats, then she can have everything: her father to want her, a girl to want her, Vietnam to want her. She’s not the only one who desperately wants, either: Ba wants his family back with him in this house their ancestors never got to claim. Both of them want to leave their mark on a homeland they never fully got a chance to know and be known by.

It’s crucial that this hungering has bloomed against the backdrop of colonialism and conflict. Hunger is defined in opposition to fullness; it’s a negative space state. Jade’s parents were forced toward America by conditions created by the war. Their family has a connection to Nhà Hoa’s ghosts because Jade’s great-grandmother served the French, who needed a holiday destination in the country they’d taken over. Even the ghostly bride is really only another victim of the house’s true mistress, exiled from her family by the marriage. This severance and diaspora–the fractures still webbing the characters in the present day–were created from imperial dispossession. Lack of fullness. Negative space state.

Who is eating whom? Jade asks. She and her father both hunger to be hungered for; even the house wants to be intimately known. It’s a vicious desire that starts changing them all from the inside. But there’s the dispossessed and the possessive: like the fungus Jade finds bursting through the heads of the ant colony outside, the French came in and only devoured.

***

Parasite, noun: an organism that lives in or on its host and benefits by feeding from it at the other’s expense. There are possibly several hundred thousand species of parasites in the world. As Jade so helpfully catalogues, they can be anywhere: tapeworms in your pork, brain viruses transmitted through mosquito bites, amoeba in your salad, flesh-eating bacteria in an oyster. Parasites live alongside their hosts for an extended period of time, feeding and feeding. In some cases, they even take over enough to control their hosts’ behaviour. The ant parasite in this book is O. unilateralis, a cordyceps that enthrals its host to anchor itself to a leaf, release new infectious spores, and wait to die. If just a single spore takes root, it can take over an entire colony.

France gained control of Vietnam in 1887 following the Sino-French war. By the early 1900s, they started setting up a resort town in the highlands of Đà Lạt, the City of Eternal Spring, where they built luxurious villas like Nhà Hoa to escape the tropical heat. The cool climate, however, also made areas like Đà Lạt ideal for coffee and rubber plantations, which fed titans of European industry like Michelin. The working conditions provoked events like the communist strike in 1930. Some sources suggest that at their peak, death rates in some of the biggest plantations went up to 47% .

“Bones pile at the table’s center, the remains of our ongoing feast,” Jade observes of their family dinner. 19th-century plantation worker Tran Tu Binh wrote that the Vietnamese “bec(a)me fertilizer for the capitalists’ rubber trees” . Now, there are skulls in Nhà Hoa’s garden still feeding the soil, where French soldiers executed locals and posed with the severed heads. The people of this colonie d’exploitation were expendable.

At its core, colonialism is the biggest insatiable appetite. It takes and doesn’t care to serve anyone else at the table. And like every other meal in excess, its effects linger long after it’s ended.

***

But to eat can also mean to reclaim.

Such a big part of the colonialist agenda is memory. Legacy. Heritage. Power is being remembered, for your cultural fingerprints to shape history and be seen in the foundations of the future. “I will never be forgotten, but you will be nothing at all,” Marion Dupont tells Jade, who’s self-conscious about her stumbling Vietnamese and feels like a tourist in the place of her parents’ birth. For all their differences, both Jade and her father desperately want to feel like a part of Vietnam, like a survivor crawling out of the blight and screaming I am here.

Maybe reclaiming a legacy is taking back a French house and giving it a Vietnamese name. Or it’s lists of dead Vietnamese workers, emblazoned online like a cenotaph in pixels. Or maybe it’s finding your great-grandmother peeking into the side of her masters’ family picture–le sauvage l’a ruinée, ruined by the savage–and tucking the photograph among your treasures (she was there).

And maybe it’s in the food.

Even when cities become unrecognisable or when languages, cultures and faiths were plastered over by colonial rule, food persists. More than that, people took and remade and re-owned, even in places where–as Jade notes of her great-grandmother–they were “meaningless except for the production of food”. Bánh mì sprung from French baguettes; Singaporean Hainanese pork chops were created by Hainanese chefs working in European households. Decades after independence, when the Nguyens sit at the table their ancestors could only serve at but are now eating Vietnamese food the same way they made it, it is a small but fierce kind of victory: “this place as ours, this place as healing”. All that insistence on describing the food then feels a bit like drawing a line in the sand.

And when Jade says she doesn’t feel Vietnamese enough to have an opinion on anything other than what makes a good bánh mì or phở, I think about how food is the most easily reachable part of a distant identity. For diaspora kids–or cultures that have gone through such rapid change between generations that we may as well be, like in Singapore–food is often the biggest part of the culture that does get brought across. Even when you barely share the same languages or land, your tongues know the same tastes. Food forms a speculative identity in itself, a cultural imagination. You eat therefore you are.

My dad’s native language is Teochew, although he’s trilingual in English and Mandarin. His parents, my grandparents, did not speak English at all. I do not speak Teochew–I was never taught and speak only faltering Mandarin–but still I know how to say “eat”. Jiak. 吃.

The sound punctuated weekends and holiday meals. I know how to call people to the dinner table, the fixture of my memories with my grandparents now that they’ve both passed away. I was never able to really talk to them. But I knew the taste of my grandmother’s ngoh hiang, of the 爱心汤 she made every Chinese New Year or the Teochew porridge dishes I can’t name, the bags of fruits she used to make us take home or the prawns my grandfather would continue to offer me, years after I became vegetarian.

All these dishes, of course, were first brought over centuries ago by the original Teochew and other Chinese migrants who came to Singapore to find work. The history of food is a lineage of people and migration. Food fills in the gaps time and trauma has left in family histories. Food is how we carry on what was left behind. The palates of immigrant nations are made of the dozens of cultures that wove their tastes into the tapestry: there is no conceivable Singapore without East and South Asian migrants meeting the Nusantara flavours; no conceivable United States without the kitchens of Latin America, Chinatowns, Little Saigons. Food is not, perhaps, a mark on Vietnam, but a mark from Vietnam carried over to the new world. Threads hooked across oceans and bodies and time.

The novel opens at the mouth of the house and ends at its heart, beating, burning, wanting, waiting.

Wen-yi Lee likes writing about girls with bite, feral nature, and ghosts. A Clarion West alum from Singapore, her work has appeared in Strange Horizons, Nightmare and Uncanny, among others. Her debut novel, The Dark We Know, is forthcoming in 2024 and is also about a haunted angry bisexual Asian girl. She can be found on social media at @wenyilee_ and otherwise at wenyileewrites.com.