Maybe it shouldn’t have taken so long, but by the time I reread the seventh Sandman collected edition, Brief Lives, I realized that the first four years of the series, at least in their trade paperback incarnations, follow a three-fold cycle. It goes like this: quest, aid, and potpourri. Then repeat. Those probably aren’t the super-official terms, and Neil Gaiman may have his own morphological constructions in mind, but the pattern remains true nonetheless.

The first story arc was Dream’s quest to retrieve his implements of power, the second was largely Rose Walker’s story with Morpheus in a pivotal supporting role, while the third was a collection of single-issue stories outlining different corners of the Sandman universe. The cycle repeats with the next three story arcs, as Season of Mists sends Dream on a quest to rescue Nada from Hell, while the follow-up primarily focused on Barbie’s fantasy world, and the Fables and Reflections once again gives a variety of short tales which involve the world Gaiman has created.

Quest. Aid. Potpourri.

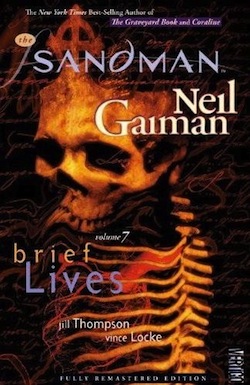

Which means that Brief Lives must be a quest, starting a new cycle for Sandman. And it is, but now that the series is past the halfway point, the cycle picks up speed. Everything becomes more compressed, so Brief Lives is a quest that also positions Morpheus as an aid for Delirium who is on a quest of her own. It’s a QuestAid, which sounds like it might very well have been the name of a Commodore 64 program designed for role-playing support circa 1985. This one, by Neil Gaiman and Jill Thompson, is better than that hypothetical one.

Better, though far from perfect. Unlike A Game of You, which I appreciated a lot more during this reread, Brief Lives loses much of its power as it ages. Gaiman and Thompson still provide plenty of entertaining moments, and the requisite bits of pathos and tragedy and introspection (because, hey, it’s a Sandman story arc), but when this story was first coming out as a serialized comic, it’s central impetus—the search for the missing member of the Endless—was a capital-B, capital-D Big Deal. Or it felt like it was one at the time.

Before Brief Lives, we don’t know much about Destruction, brother to Dream and Delirium, or why he has stepped away from his duties, never to be spoken of again. (Except by Delirium, who remains childlike and innocently impulsive and unable to understand why some topics are off limits.) Learning about Destruction, who he was and how he came to abandon his post, was one of the more fascinating aspects of the story as originally serialized. Perhaps it still holds that kind of power for new readers. But for returning readers, or at least for me, Brief Lives seems, ironically, less than brief. It’s a bit wearying.

As I was preparing to write this reread post, I flipped to some random pages of the collected edition to refresh my memory about what I wanted to highlight the most. Almost every page I flipped to showed the hyper-kinetic Delirium rambling on about something while Dream solemnly ignored her, or spoke to her in matter-of-fact tones. There’s a lot of that in Brief Lives. It’s so abundant that it almost becomes a parody of itself, like you could imagine a webcomics series in the vein of Ryan North’s Dinosaur Comics in which the bubbly Delirium and the somber Dream take a road trip and every installment uses the same four panels, with three panels of Delirium’s crazy-childlike chatter and the final panel with Dream’s deadpan retort. Brief Lives is like the soap opera meets Hope and Crosby meets Neil Gaiman and Jill Thompson version of that gag strip, with fewer gags.

Aside from the increasingly tedious relationship between Delirium and Dream, and my not-so-subtle mockery of said relationship, Gaiman and Thompson do give us some things to brighten up the reading experience. Some of it’s tragic, as it turns out that Destruction doesn’t want to be found, and he’s left some traps along the way which cause some collateral damage to the travelling companions of the two seekers. Yet that provides some interesting situations, and nearly causes Dream to abandon the trip forever.

Destruction, when we finally meet him, is portrayed like a yuppie who has gone bohemian. Like an heir to a big city banking kingdom who has abdicated his fortunate throne to paint landscapes and hang out with his dog on some quiet island. He’s vibrant and gregarious, and unlike all the non-Death members of the Endless, seemingly happy with his existence. He’s the poster boy for early retirement.

Philosophically, Gaiman uses Destruction, and his interaction with his siblings when they finally track him down, to express a perspective on what it all means. Destruction comments on the role played by the Endless: “The Endless are merely patterns,” the prodigal brother says. “The Endless are ideas. The Endless are wave functions. The Endless are repeating motifs.” He wanted to break free from that narrowly defined, prescriptive role. And he knew that things would continue to be destroyed and new things built even if he, as the steward of the very concept of Destruction, was no longer responsible. The ideas were already set in motion. The machinery of the universe would see to it.

As a foil, Destruction pits Dream against his own sense of responsibility. What’s evident, in reading Sandman as a whole, is that so much of the story is based around acceptance. Acceptance of life, of death, of reality, of unreality. Acceptance of responsibility or utter rejection of it. Think of those who step forward to continue Dream’s work while he is imprisoned for all those years. Then think of Lucifer, who abandons the very underworld that defines him and gives the responsibility to someone else. Think of Morpheus, who spends almost the entire series attempting to reclaim and rebuild his Dream kingdom in just the right way—always tasking Merv Pumpkinhead with new renovations—and then finally accepting that he is destined to be replaced by a new incarnation.

Dream has got to be one of the most passive lead characters in comic book history, always reflecting and reacting, and then waiting to die, as a swirl of other people’s stories surround him. But Gaiman still makes the character seem incredibly substantial. And because Morpheus is the lord of imagination, all stories are, in a fundamental way, his as well.

Brief Lives seems positioned as a story arc where Gaiman wanted to do two things: put Delirium and Dream in a car and have them interact with humanity (and special emissaries around the globe who recall a time when magic was more prominent on Earth), and to reveal the nature of Destruction to set the series toward its tragic conclusion. For as I mentioned in my reread of the “Orpheus” story in Fables and Reflections, what happens to Orpheus is a small-scale parallel of what happens to Dream. The son’s story becomes echoed in the father’s.

And in Brief Lives, the Sandman kills his son.

All that was left of Orpheus—granted deathlessness by his aunt so he could rescue Eurydice from the Underworld—was his head, and that oracular visage had been kept secure for generations. But after his meeting with Destruction, Dream goes to his son and lets him get his final rest. It’s an act of mercy, while keeping him alive had been an act of spite. Dream accepts responsibility for what he does, what he has to do, to set his son free.

Dream has grown, as a character, through his interactions with the world—but mundane and mystical—and I suppose that’s the major point of Brief Lives, amidst all of its journeying and philosophizing and Endless banter. Morpheus matures. And move one step closer towards death, though he doesn’t yet know it.

NEXT TIME: We step away from Sandman for a moment as Sexton meets Didi in a spin-off called Death: The High Cost of Living.

Tim Callahan hopes that Delirium Comics (featuring Morpheus) becomes a meme, because he would read those hilarious four-panel interactions all day every day. Unless they were not funny.