Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

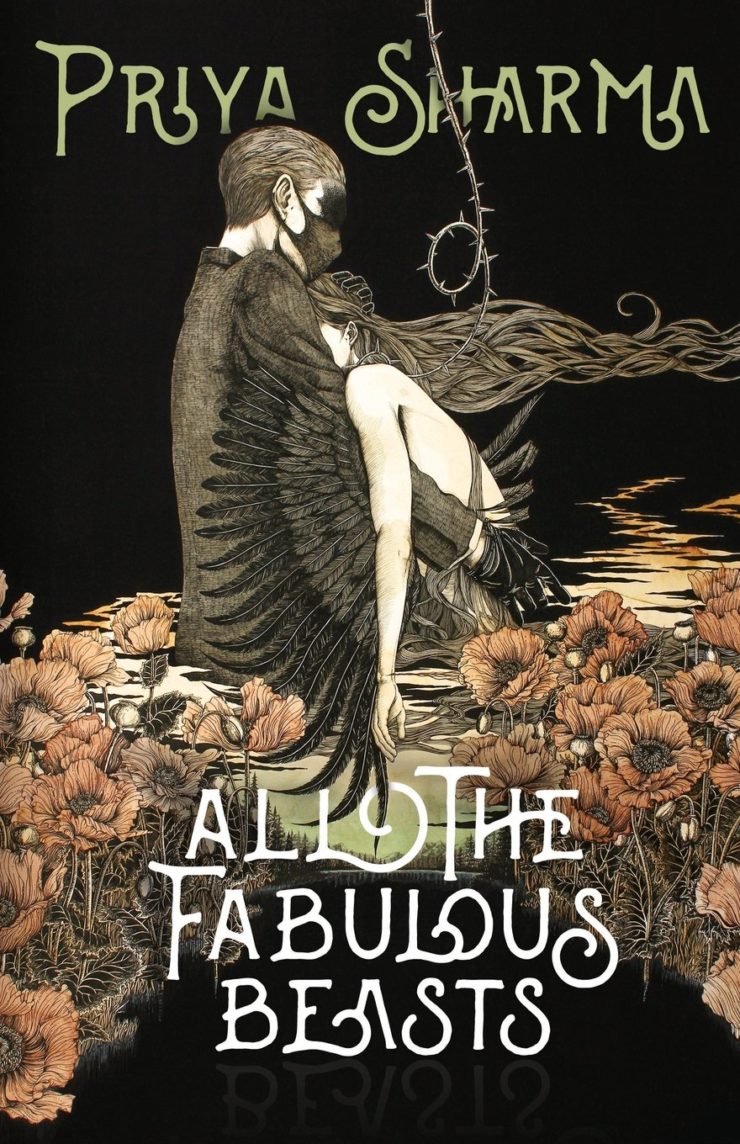

This week, we’re reading Priya Sharma’s “Fabulous Beasts,” first published here on Tor.com in July 2015. It was shortlisted for the Shirley Jackson Award, and All the Fabulous Beasts, Sharma’s collection containing it, is on this year’s shortlist (which is how we encountered it). As the original Tor.com publication warns, this story (along with our post about it) deals with difficult content and themes, including child abuse, incest, and rape. Spoilers ahead.

I looked into the snake’s black eyes and could see out of them into my own. The world was on the tip of her forked tongue…

Summary

Narrator Eliza and partner Georgia move among London intelligentsia, politicians and actors and journalists who call Eliza “une jolie laide,” ugly-beautiful. Many accost her to demand her “secret.” Her answer’s truth, and lie: “I’m a princess.” Kenny did call her his princess, but actually she’s a monster—and her real name’s Lola.

Once Kenny’s princesses lived in a tower—Laird Tower, a decaying apartment building in a decaying city. Kath is Lola’s mother. Ami, Kath’s sixteen-year-old sister, has given birth to Tallulah Rose, as gorgeous as four-year-old Lola’s homely: flat-nosed, ears squashed to her skull.

People whisper whenever Kath and Lola walk to the shops. One Saturday Lola slips into “Ricky’s Reptiles.” She’s drawn to a tank housing a snake that undulates against the glass. Lola sways in time. Kath drags Lola away, furious.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Ami loses interest in Tallulah, and leaves her in Kath’s care. The cousins live like sisters. Ami mentions one afternoon she’s visited Kenny, showed him a picture of Lola. Why’s Kath so mad? Kenny only wants to look after them, show some respect. Respect, Kath retorts, for a man in prison, who beat another man to death? Well, Ami says, he is our brother. It’s the first Lola knows she has an uncle.

Eliza, grown, is a herpetologist. When she milks venom with witnesses, she pretends to restrain the snake. Alone, she knows it’ll cooperate. She and her charges adore each other.

School bully Jade asks Tallulah if Lola’s her sister, denies it in the same breath: Look at Lola’s ugly mug. Tallulah pushes Jade, and Lola bites her forearm, drawing blood. Jade falls, arm red-streaked. Later Jade’s mother begs Kath to reassure Kenny—she’s punished Jade and isn’t the one who called authorities. She’ll never nark. But Kath beats Lola, calling her a monster just like her (normally unmentioned) father.

Tallulah comforts Lola, who senses change coming. She rubs her face until the skin peels off. Her bones remold, limbs shrinking, organs shifting. When Lola’s shed her skin completely, Tallulah gathers up her scaly length, and Lola flicks her forked tongue to taste her “every molecule in the air.”

Morning come, Lola’s human again. Is she a monster, she asks. Tallulah answers: “You’re my monster.”

Lola’s eighteen when Ami brings home the freed Kenny. He tells Lola she’s got the family’s ugly gene, like him and Kath. But she’ll do.

That night, Kath tries to pack and leave. When Lola protests, she gives up, admitting she waited too long. But for Ami and Tallulah, she’d have escaped with Lola long ago. Lola begins to understand why when Kenny talks about how, after their family lost its fortune, he had to provide for his princess sisters. His gang went after a jeweler said to have stolen diamonds. The jeweler wouldn’t cooperate; one of Kenny’s mates killed him, but Kenny did the time for it.

Kenny visits often, making excuses for his criminality: He “only became brutal to stop us being brutalised.” Once a boy picked on Kath, and Kenny bit him, swelled his face like a red balloon. So, is Lola special too? Lola refuses to answer.

Kenny’s not interested in obviously unspecial Tallulah. Kath and Lola he takes to the old family house. The windows have new iron bars wrought like foliage and snakes; the door he locks himself. Lola eavesdrops as Kenny reclaims Kath as a lover; Kath goes along with obvious reluctance. He says he stole the jeweler’s diamonds before admitting his mates, and now “Shankly’s looking after them.” Kath tries to persuade him to release Lola—unsuccessfully.

Later Kath tells Lola that Kenny never gave her a choice, only informed her they’d make a baby who’d be special “like [him] and Dad.” Only he’s wrong—their mother was the special one, though she always fought the transformation. Kath urges Lola to crawl through the window bars, while Kath does a long-delayed duty. She pats the paring knife in her pocket.

Next afternoon Kenny shows Lola a freezer in which “traitor” Kath lies dead. Then he shows her his snake room. In one tank lies a cottonmouth named “Shankly.” Is Lola special, Kenny asks again. Like him? Lola tells him not to touch her. When Kenny shoves her to the floor, she pleads that she’s his daughter. “I know,” he says, and puts his forked tongue in her mouth.

After the rape, Kenny leaves Lola too numb to move. Someone calls her; through the window bars she sees Tallulah’s pale face. Then Tallulah’s gone—a slender yellow-marked snake crawls inside. Lola too transforms. Moulting’s good, shedding every cell Kenny’s touched.

They crawl to Kenny’s room. While Lola engulfs his head in her jaws, Tallulah strikes venom into his neck. Kenny tries to transform, weakens, dies. Human again, Lola digs money and diamonds from Shankly’s tank. They release Kenny’s snakes, bring Shankly along.

Kenny’s stash is the foundation for their lives as Eliza and Georgia. Though Lola still struggles with insecurity, when she asks a trip-returned Tallulah if she loves her, they shed their skins to knot together, to hunt mice, to wake human, entwined. That’s when Tallulah says, “Of course I love you, monster,” and it’s all right. They are monsters.

Fabulous beasts.

What’s Cyclopean: Eliza’s “une jolie laide,” which sounds a lot like attraction-repulsion, and also not a nice way to talk about people at parties.

The Degenerate Dutch: The difference between Tallulah’s beauty and Lola’s reptilian ugliness is so striking that no one notices how much they have in common.

Mythos Making: Inner monsters and dreadful familial secrets crop up across the Weird, from the Martenses to the Penhallicks and from Innsmouth to Innsmouth.

Libronomicon: No books, but we do get a glimpse of Tallulah/Georgia’s gorgeous photography. Lola’s hair is “loose and uncombed and the python around my shoulders is handsome in dappled, autumnal shades.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: No generic or hyperbolic madness this week; Sharma’s unblinking focus in this story is on PTSD and the aftereffects of trauma.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Lovecraft—the man himself as well as Frank Belknap Long’s fictionalized version—would have it that the truest horror builds not off of everyday human fears, but off existential alienation distilled into perfectly inhuman creations. These horrors ostensibly depend entirely on the skill of the author, rather than on preexisting survival instincts. In practice, of course, these eldritch horrors depend on the reader’s everyday experiences of alienation, on their ability to imagine across the gap from pedestrian horror to fantastical.

Sharma’s fantastical doesn’t hyperbolize the real-world horrors—horrible enough, here—but instead limns them, making them nastier in a couple of places and balming them in others. Kenny’s abuse, his incestuous rape of Kath and Lola, Ami’s simpering insistence on family togetherness, the generational backlash shadowing Lola and Tallulah’s childhoods, are not made worse just because some of the people involved can turn into snakes. But the question of what it means to be monstrous is made sharper. And the means for escape and recovery, more fantastically cloaked than the abuse, become as fabulous a transformation as such a change should seem.

Lola calls herself a monster. She and Tallulah are monsters in the oldest sense, something strange and wondrous and not like what came before. Fabulous creatures. They’re as kind to each other as they can be, healing slowly from Kath’s “a slap suffices” parental style, channeling their strangeness into talents they can share with others. But morally, they’re just people who got themselves out of a horrible situation—Kenny’s death is certainly no loss to the world.

He, on the other hand, seems to have latched onto his inner snake as an excuse for a deeper monstrousness. But then, people like him will find an excuse. Something that justifies or excuses their actions, that proves them above all those other people and their qualms. It’s as banal in a weresnake as in the sort of abuser whose tongue is only metaphorically forked. I appreciate, intensely, the degree to which Sharma shows Kenny charming other characters without making him charming to the reader. Some narratives fall in love with their villains, and some villains are worth falling in readerly love with; this guy is just a douchebag.

For all that their whole family is full of snakes, Lola and Tallulah are the only ones who use their serpentine powers to change their lives. For Kenny it’s more a symbol and an excuse, something that makes him “special.” For Kath (who may or may not be able to do it at all), it’s tied up with Kenny’s horrors, something to be resisted and feared and attacked. And for Kath and Kenny’s parents… I have a suspicion that the father was the one who convinced their mother to be frightened of her own power. Kenny never actually saw either of them change. He just assumes it was their father… because douchebag, or because patriarchy, or both. Because whatever power his father did demonstrate, it was the sort that he recognized.

Kenny is, in general, willfully oblivious to female power. His mother’s, but also Lola’s, the mere possibility that she might strike back at him. Even Kath’s—he kills her, but he never expected her to rebel at all, or to teach her children to be anything less than fearfully loyal. So the way his actions pass down the generations, his vulnerability to the hatred he’s earned, come as a shock—at least briefly.

Anne’s Commentary

Full disclosure: I love snakes. Fuller disclosure: I love venomous snakes. Fullest disclosure: As a kid, I secretly pretended to be a king cobra. I’d hunt for other snakes around the house; they were always found in the refrigerator, in the guise of natural casing franks, long coiling links of them. My favorite YouTube channel is Viperkeeper. Nothing’s more relaxing than watching a guy feed snakes thawed rodents, clean out enclosures, wrangle mambas and cobras and lanceheads, and (best of all) assist them out of stuck eye-caps and sheddings. That’s entertainment.

Any wonder I test as Slytherin (with a side of Hufflepuff, because I’m nice, really I am)? Any wonder I ponder what kind of snake Voldemort’s familiar Nagini must be (a Burmese python in size and shape, but venomous with recurved fangs and skin patterning as elaborately geometrical as a Gaboon or rhino viper’s)?

Is it any wonder I love “Fabulous Beasts”?

Not only does it feature snakes, it has an elegant patchwork structure of present-past narration and finely balanced description, neither copious nor sparse, always the telling details given, as in the tawdry cityscape through which Kath and Lola walk to the shops, as in the foliage-and-serpent bars on Kenny’s regained childhood home, as in baby Tallulah’s resemblance to idealized infants on knitting patterns. The specifically ophidian details provide the realism that tempers Sharma’s fantastic premise to fictive truth: How Lola rubs her face on carpet to start shedding, how her and Tallulah’s shed skins mirror their human forms, how Lola’s vision dims before shedding and normalizes after—her eyes have gone “opaque” as secretions between outer and inner skins loosen the former.

What kind of snakes are Lola and Tallulah? That’s uncertain even to herpetologist Lola—like Rowling’s Nagini, they’re a species mash-up, and why not, given their magical nature. Tallulah sounds like an elapid with her slim body and neurotoxic venom, but her white and yellow-marked skin sounds more like an albino python’s. All we know about Lola-snake is she has heat-sensitive pits letting her see in thermal gradations. That likens her to the pit vipers, a subfamily that covers wide geography, from rattlesnakes and copperheads of North America to lanceheads and bushmasters of South America to hundred-pacers and temple vipers of Asia. If mass is preserved during their transformations, then Tallulah- and Lola-snakes are huge, Lola having the swallowing capacity of an anaconda more than a pit viper. Tallulah and Lola make a great hunting pair, one presumably relying on the speed and keen sight of a mamba or cobra, the other on thermal night-vision, both on chemical signatures fork-tongue gathered.

What Kenny’s snake form is, we don’t see. Lola’s glad—understandably, she can’t imagine it would be pretty. Kenny’s a monstrous monster, whereas she and Tallulah are fabulous beasts, to be victims no longer once they come into their metamorphic heritage. That puts them on the opposite end of the spectrum from many transformed in Greco-Roman mythology, like Actaeon, turned by Artemis into a stag whose own hounds drag him down. It also contrasts them with Mercè Rodoreda’s hapless witch turned salamander. The salamander shrinks down to vulnerable newt-size, is tormented by humans and eels, can’t transform back. The ability to reverse-transform is advantageous in human-animal metamorphosis, giving Lola and Tallulah the best of both taxa, Serpentes and Homo. Whereas Rodoreda’s narrator is stuck with her new amphibian form. Worse, she’s just as passive and put-upon a newt as she was a woman.

Not so Tallulah and Lola. They bring into snake-form all their human spunk, Tallulah’s brash, Lola’s persevering. The moral being that in trans-form we’re still our essential selves. Or even more our essential selves?

To deepen one’s essence in animal form could be a curse or a blessing, then. I’d say transformation triggered by external force is more likely to be a curse than transformation triggered by internal proclivity. Kenny, Lola and Tallulah all have the genotype to serpentize, though only Kenny and Lola have the “Slithering One” phenotype, analogous to the Innsmouth Look.

Speaking of Howard, his snakiest stories are “The Nameless City” and superlatively his collaboration with Zealia Bishop, “The Curse of Yig.” Where baby-rattler killer Audrey Davis is concerned, Yig’s transformative curse may be external, magically imposed by him, or internal, the product of her trauma-induced madness. Either way, she’s left writhing and hissing like her victims, eventually to lose her hair and gain a blotchy skin. The reader might accept Audrey’s transformation as psychosomatic. It’s harder to explain away the offspring she bears after Yig’s “visit.” I fear an external trigger, that is, Yig’s physical or magical insemination of their mother.

Anyhow, Howard in general didn’t like transformations, fantastic or social. Whereas Sharma allows Lola and Tallulah to bask in theirs. A happy ending, complete with well-deserved revenge.

I can wrap myself all around that. Ah, if only.

Next week, we turn back to The Secret Life of Elder Things to cover the missing third of its authorial trio in Adam Gauntlett’s “New Build.” Who’s a good hound? Is it you? Are you a good doggy? (Somehow, we suspect the answer is no.) After that, possibly further dives into the latest crop of award nominees…

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.