Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

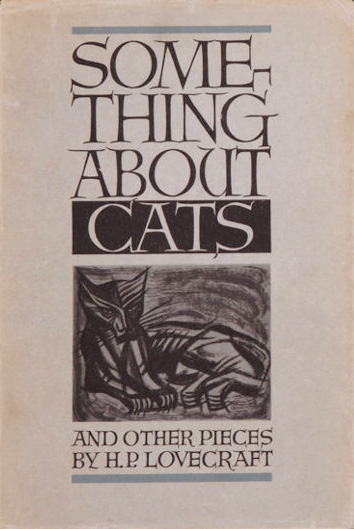

This week, we’re reading Sonia Greene’s “Four O’Clock,” first published in Something About Cats and Other Pieces, edited by August Derleth, in 1949—but written considerably earlier. Some sources list Lovecraft as a co-author but there’s no particular evidence for this. Spoilers ahead.

“The vapor each moment thickened and piled up, assuming at last a half tangible aspect; while the surface toward me gradually became circular in outline, and markedly concave; as it slowly ceased its advance and stood spectrally at the end of the road. And as it stood there, faintly quivering in the damp night air under that unwholesome moon, I saw that its aspect was that of the pallid and gigantic dial of a distorted clock.”

Unnamed narrator has, through some unnamed circumstance, come to an unnamed (but well-remembered) house in an unnamed locality on the very night when he should not be there. At two in the morning, he lies in a (well-remembered) bedroom whose east windows face an ancient country cemetery, unseen because the shutters are closed. Not that narrator needs to see the cemetery, for his “mind’s eye” shows him its “ghost-like granite shafts, and the hovering auras of those on whom the worms fed.” Worse, he imagines all the “silent sleepers” below the grass, including the ones who “twisted frantically in their coffins before sleep came.”

The thing too horrible for narrator to imagine is what lurks in his grave—that of some unnamed someone connected to narrator in some unnamed fashion who suffered some unnamed catastrophe on some unnamed day at the (at last something definite) hour of four a.m. Apparently the injured party held narrator responsible for the catastrophe, though narrator contends he can’t justly be blamed; before the injured party died, he prophesied that four a.m. would also be the hour of narrator’s doom. Narrator didn’t really believe this, because who listens to the ravings of vindictive madmen? Now, however, the “black silences of night’s depth and a monstrous cricket chirping with a persistence too hideous to be unmeaning” convince narrator the coming four o’clock is to be his last.

No wonder narrator tosses and turns and can’t lapse into the merciful arms of sleep.

Though the night is windless, a sudden gust tears open the shutter of the nearest window. In the moonlight scene thus disclosed to his waking eyes, he perceives a fresh omen: From the direction of the madman’s grave flows a grayish-white vapor. At first formless, it gradually shapes itself into a concave circle that stands at the end of the cemetery road “faintly quivering in the damp night air under that unwholesome moon.”

Narrator recognizes it as “the pallid and gigantic dial of a distorted clock,” bearing in its lower right-hand sector a black–creature? Anyway, the half-seen thing has four claws that form “the numeral IV on the quivering dial of doom.”

The dial-beast wriggles out of the clock face and approaches narrator, who sees that its claws are “tipped by disgusting, thread-like tentacles, each with a vile intelligence of its own.” He’s appalled not only by this apparition but by cryptic nocturnal noises that remind him of the approach of FOUR O’CLOCK. The persistent cricket now positively shrieks the dreaded hour, and on the fresh-painted walls of the room dance “a myriad company of beings…the aspect of each [being that] of some demon clock-face with one sinister hour always figured thereon–the dreaded, the doom-delivering hour of four.”

Outside, the grave-spawned monster has morphed from gray mist to red fire. Its tentacled talons whip the wall clock-faces into a “shocking saraband” until “the world was one ghoulishly gyrating vortex of leaping, prancing, gliding, leering, taunting, threatening four o’clocks.” Early morning wind soughing over the sea and marshes swells to a “whirring, buzzing cacophony bringing always the hideous threat ‘four o’clock, four o’clock, FOUR O’CLOCK.’”

For narrator, “all sound and vision… become one vast chaotic maelstrom of lethal, clamorous menace, wherein are fused all the ghastly and unhallowed four o’clocks which have existed since immemorial time began, and all which will exist in eternities to come.” Fiery claws advance on his throat; outside, through the graveyard vapors, the clock-face resolves into “an awful, colossal, gargoyle-like caricature of his face–the face of him from whose uneasy grave it has issued.”

It seems the “madman” was in fact a “potent fiend” determined to wreak vengeance on innocent narrator. And on the mantel a timepiece whirs to presage “the hour whose name now flows incessantly from the death-like and cavernous throat of the rattling, jeering, croaking grave-monster before me—the accursed, the infernal hour of four o’clock.”

What’s Cyclopean: Many “indescribable” things are nevertheless described, to include “noxious fatality,” “tenebrous silence,” and “sphinx-like sea and febrile marshes.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Our narrator’s too focused on impending Scheduled Doom to care about other living humans, let alone their ancestry.

Mythos Making: Tentacles!

Libronomicon: No books this week; maybe our narrator should’ve taken a copy of the Necronomicon along for bedtime reading.

Madness Takes Its Toll: “The prophecies of vindictive madmen” are seldom to be taken with seriousness—except in horror stories, where they should always be so taken.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

My fascination with Lovecraft’s collaborators is multifold. Some of it is the insight into his own work: the things that show up across co-authors highlight his own style, while the strengths of particular co-authors (Heald and Bishop, mostly) highlight his limitations. Greene, who only wrote one story with him and two on her own, brings another fascination: the perennial question of how the hell these two weirdos ended up married.

“Four O’clock,” I confess, doesn’t fascinate much on its own merits. I shouldn’t say that it shows why Greene was primarily a sponsor of and commenter in zines, rather than a contributor of fiction, because frankly it’s no worse than many of Lovecraft’s own amateur publications. Like those, it’s a mood piece built on a couple vivid images and an excitable vocabulary. Greene was not, as far as I know, as prone as Lovecraft to recording the exact timetable on which stories were constructed, but I’d wager this one was written in a single night of nightmare-ridden insomnia. The plot isn’t the point. Why did the madman curse our narrator with his dying breath? Is he really innocent? How did he end up back at the scene of the maybe-not-a-crime? Never mind all that, it’s 3 AM and there are clock-taloned tentacles on the march!

It’s often struck me how unlikely Greene’s and Lovecraft’s marriage should’ve been. The man was, after all, anti-Semitic among his many other bigotries—Greene’s insistence on talking about his prejudice was, in fact, one of the things perennial nemesis August Derleth held against her. This time out, though, it occurs to me that maybe it’s not so weird. Lovecraft’s own culture prized stoicism and unflinching action—things he approved of but certainly didn’t practice. Maybe a neurotic guy with a penchant for combining scholarly language with emotional rants… would’ve fit better in a crowd of yeshiva boys than a parlor full of post-Victorian WASPs, if only he could have gotten over his xenophobia. And Greene herself may have appreciated a man actually willing to talk with girls about shared geekeries—doubtless even rarer then than it is now. As long as they kept the conversation to amateur press gossip and the terror of tentacles, rather than politics or religion, they’d be fine…

The clock-tentacle monster is weird enough to suggest a fair amount of potential—and hints at temporal terrors to match Lovecraft’s own. Is it the madman’s curse that schedules it so perfectly, or is there something inherently terrible about trains-on-time-style deadliness? This interests me far more than the backstory we aren’t told (but could fill in from a list of standard tropes). Lovecraft’s into time frames too vast to comprehend with the human mind; Greene makes the clock itself inhuman and a perfectly measurable two-hour period fraught with eldritch meaning. I rather wish she’d written more, and plumbed some of those depths.

Anne’s Commentary

And here we thought that three o’clock was the witching hour and dark midnight of the soul. Four o’clocks are also plants of the genus Mirabilis, notable for fragrant trumpet-shaped flowers that open around four o’clock, but that’s four o’clock in the afternoon, so they couldn’t have figured in the predawn torment of our narrator. Given his extreme sensitivity, though, any encounter with the innocuous little blooms would probably have given him shivers of premonitory dread.

Casual grazing upon the fecund fields of the Internet has informed me that, rather than revising “Four O’Clock,” Lovecraft may only have discussed it with future wife Greene during their 1922 field trip to Magnolia, Massachusetts; in a letter to Alfred Galpin, Lovecraft mentions that among Greene’s story bunnies was one with “some images noxiously Poe-esque”–and by “noxiously,” we all know that Howard meant high praise, not censure. I agree with him about the Poe-esqueness of “Four O’Clock,” not just as regards its imagery and diction but also its overwrought protagonist.

Speaking of overwrought protagonists, it’s piquing to read in a 1948 Greene letter that she has sent Arkham House a fiction she “wrote about HP a few months after I met him, but at his request I did not publish it…because, as he told it, it was obviously a description of himself.” In 1949, Arkham House published two Greene stories in its collection, Something About Cats and Other Pieces. One was “The Invisible Monster” (aka “The Horror at Martin’s Beach”), the other was “Four O’Clock.” Since “Invisible Monster” was published during Lovecraft’s lifetime (Weird Tales, 1923), we can infer that it’s “Four O’Clock” which supposedly featured her own Howard.

Most wouldn’t consider it flattering to be portrayed as a doomed innocent (or maybe not so innocent, given how much he protests.) Most aren’t Howard and friends. They took delight in fictionally slaying one another–a prominent example being Robert Bloch’s “Shambler from the Stars” and Lovecraft’s “revenge,” “The Haunter of the Dark.” Yet per Greene, Lovecraft didn’t want her story published. Maybe he didn’t like being portrayed as stupid enough to be in exactly the wrong place at the wrong time, curse-wise. Or maybe he perceived “Four O’Clock” as flirtation, or even a love letter, hence not suitable for public consumption? Private fanfic, if you will.

Anyway, what strikes me most about “Four O’Clock” is its structural reliance on a single image or concept: the last-gasp-of-night as scariest hour of the day, perfect time for a rendezvous with posthumous payback. This story is all about FOUR A.M., baby. Spectral clocks relentlessly display the hour; the nocturnal chorus chants and shrieks its name, led by a malevolent cricket. The fixation leads to a piece more tone-poem than narrative. In fact, the narrative is skeletal, all the meat of background detail stripped (or rotted) away. That the narrator’s unnamed, well, we’ve come to expect that of half our tales. But everyone and everything else is unnamed, too. Who’s the vindictive madman, what relation to narrator? Where is the country house and cemetery? What happened to the vindictive madman one dark four o’clock to make him so vindictive, and why does he blame narrator for it? Is narrator really innocent? What is the “circumstance” that lands him in the very spot he should avoid, at the very time he should be a thousand miles away? Why doesn’t he spend the 120 minutes between two and four getting the hell out of the “well-remembered” house? Does he subconsciously feel guilty, deserving of his fate? Does he actually enjoy having the crap scared out of him?

We don’t know. Do we need to know? That’s a question of reader taste: Do you crave a fleshed-out narrative or can a skeleton in lush grave-cerements satisfy you? Third possibility: Could be you see the cerements not as lush but as garish, comical, “Four O’Clock” as a parody of the pulp Poe-esque. Or is it more celebratory, a pastiche? Dare I speculate, a sort of exploratory love-offering?

Too late, I just speculated.

To twist-fall with feline agility from the lofty heights of authorial intention to earthy matters of craft, let me further speculate that “Four O’Clock” is the result of an idea in search of a plot. I have much personal experience with this problem. An image may occur to me in a dream, or I may see a painting or photograph, or I may hear a snatch of conversation, and damn, another bunny has just hopped into my potential-stories hutch! To ease the overcrowding, I may grab a bunny before it’s grown into fully fleshed-out narrative and do what Greene’s seemed to do–let the raw-boned idea just run, full of itself, the trappings of fictive maturity be damned, possibly cohesion and elegance among them.

Which, yeah, could be to say that “Four O’Clock” is neither particularly cohesive nor elegant. But it has a certain vigor whether you view it as straight horror or horror-humor. With its insistence on the damn creepy clocks and the unavoidable perils of time, it reminded me of Salvador Dali’s “Persistence of Memory.” How would you like to go through life with a melted watch dial on your back, always reminding you of the crawl of hours to that ultimate hour, when you’re going to have SOMETHING to do with cemeteries, even if it’s not meeting a vindictive crazy ghost across the road from one?

And that last sentence is your essay question for today, people. Enjoy!

Speaking of Lovecraft collaborators, next week we’ll cover Lisa Mannetti’s “Houdini: The Egyptian Paradigm,” riffing on a certain ghost-written story… You can find it in Ashes and Entropy.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.