The story of Henny Penny, also called Chicken Little, or sometimes Chicken-licken (not to be confused with “Finger-licken” from Kentucky Fried Chicken), the terrified little chicken convinced that the sky is falling and that life as we, or at least as chickens know it, is over, is common throughout European folklore—so common that “the sky is falling!” and “Chicken Little” and related names have become bywords for fearmongering, and the often tragic results that occur.

Exactly where the first version of the story was told is a bit unclear, but one of the first to record the tale was Just Mathias Thiele (1795–1874), a Danish scholar employed at the Royal Danish Library. Inspired by Jacob and William Grimm, he began collecting Danish folktales, publishing his first collection in 1818. The collections proved to be so influential that Hans Christian Anderson would later dedicate a story to Thiele’s daughter. His version of Henny Penny appeared in his 1823 collection, with the familiar elements already present: rhyming names, a series of barn animals, a terror set off by something completely ordinary (in this case, a falling nut) and a very hungry fox more than willing to take advantage of the situation.

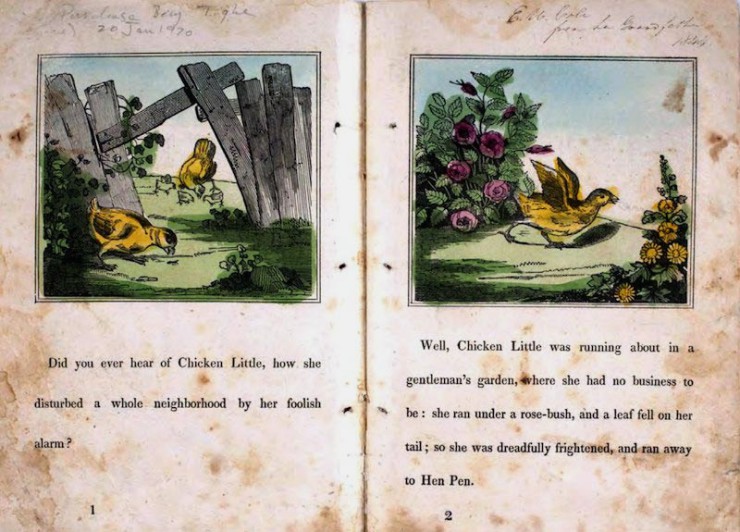

That version was not, however, translated into English until 1853. Before that, young American readers had access only to a slightly different version written and published by John Green Chandler. Trained as a wood engraver, he eventually became a lithographer and illustrator who ended up specializing in simple and elaborate paper dolls. In 1839, he set up a small printing business in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Possibly to help advertise his new business (my speculation), or possibly to help raise funds for Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument (slightly more historical speculation) or both, in 1840 his press printed a small pamphlet, The Remarkable Story of Chicken Little, featuring his texts and illustrations, available for a few cents. More recently, an internet auction sold a rare original copy for $650.

Chandler’s version is delightfully simple, if not always that grammatically correct—the story arbitrarily switches between past and present tense, for instance, sometimes in the same sentence. And I am more than a little concerned that what Chandler originally describes as something that “disturbed a whole neighborhood” turns out to be the savage murder of Turkey Lurkey, Goose Loose, Duck Luck, Hen Pen, and Chicken Little, like, ok, Chandler, granted this all turned out well for the Fox, who got to eat all of his neighbors, but the sudden death of no less than five animals, all friends, cannot be called a mere “disturbance,” as you put it.

Despite these issues, The Remarkable Story of Chicken Little caught the attention of Sarah Josepha Hale. Chandler could not have found a better publicist. These days, Hale is mostly remembered for writing “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and establishing Thanksgiving, but in her day, Hale also worked as a novelist and as the editor of influential journals focused on women, including Ladies Magazine (1828-1836) and the extremely popular Godey’s Lady’s Book (1837-1877). She had also published a successful book of children’s poetry, and was thus regarded as a reliable judge of “suitable” children’s books.

Her approval led Chandler to print out several new editions, all snatched up by young readers. His version became so popular that it may have led to the increased use of “Chicken Little” in 19th century newspapers to describe scaremongers, although it’s also possible that the journalists using the term were thinking of an earlier oral version. His daughter, Alice Green Chandler, left his papers and the remaining paper dolls and books to her cousin Herbert Hosmer, who had a serious obsession with toys, later founding a small museum dedicated to antique toys and children’s books. Hosmer was mostly interested in the paper dolls, but was also impressed by Chandler’s version of the Chicken Little story, eventually publishing—at his own expense—two versions of Chandler’s tale in 1940 and 1952, and his own poetic version in 1990.

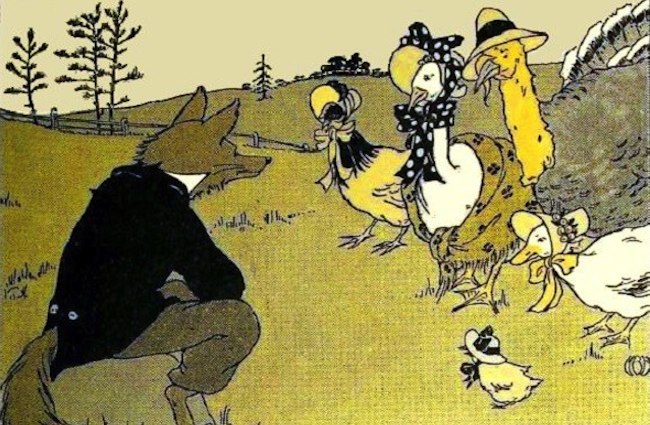

Chandler’s success inspired several other American writers to publish versions of the story throughout the 19th and early 20th century, nearly all sticking with the original rather grim ending. But if 19th century children loved that sort of thing, mid 20th century publishers were less enthralled, and began switching to versions that tweaked the ending—and by tweaked, I mean completely changed. Instead of getting gobbled up by a fox, the foolish characters instead manage to reach a king, who assures them that the only thing that falls from the sky is rain.

This is the version I first encountered, when I was about three. I didn’t like it then, and not just because The Cat in the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham were obviously better books. And I’m not fond of it now. I’m all for reassuring young children, but this altered ending just doesn’t work for me—perhaps because I find it difficult to believe that animals terrified that the sky is falling will believe any leader, even a king, who tells them the opposite, or perhaps because I am all too aware that lots of things other than rain can fall from the sky—meteors, volcanic ash, debris from falling satellites—that sort of thing. Oh, sure, that might be rare, but it happens. Or perhaps because I’m feeling somewhat uncomfortable with the basic setup here, where the silly animals get reassured by a (usually) human king; this might work better if the reassurance came from a cow. Even a kingly cow.

And if the original story, where the animals all end up mostly dead, seems a bit, well, harsh for a simple freakout over an acorn, or a rose petal, or any other small thing that just happens to fall on the head of a chicken—removing that harshness also removes the impact of the tale’s two main messages: first, not to overreact to small things, or blow them out of proportion, and second, not to believe everything that you’re told. After all, in the revised version, nothing much happens to Chicken Little and her friends, apart from a brief scare, and the chance to meet and chat with an actual king. Arguably, having to reassure them even means that he suffers more than they do, though I suppose it can also be argued that reassuring chickens is sort of his job. In the older version, Chicken Little and her followers face the real danger—and consequences—of their credulity.

That danger was the message that Disney chose to focus on in its first attempt to bring the story to the screen, the 1943 short Chicken Little, which served as a none too subtle warning to viewers to be wary of propaganda, specifically, propaganda from the Nazi party. Produced in the middle of a war, the short had what was easily one of the darkest endings of any Disney production, and certainly one of the highest death counts, and remains one of the few animated works from any Hollywood studio that includes direct quotes from Mein Kampf. A rough transfer is up on YouTube. If you can find it, I recommend the cleaner transfer available on the Walt Disney Treasures—On the Front Lines DVD, released in 2004, or on the Walt Disney Treasures—Disney Rarities—Celebrated Shorts 1920s -1960s DVD, released in 2005. Or just wait until Disney releases the short again.

By 2005, however, Disney Animation feared not Nazis, but a computer animation company called Pixar. Their take on the tale, therefore, was to be quite different.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

Something about this comment makes me chuckle: “one of the few animated works from any Hollywood studio that includes direct quotes from Mein Kampf“,

Guess it’s not something I thought I would encounter in this re-read :)

That said, I never knew there was a version where they DIDN’T get eaten by an opportunistic fox. That always struck me as in some ways the whole point, and one that is still relevant.

Thanks for all the research, once again :) I can pretty safely say I knew pretty much nothing about this story before hand.

I don’t remember how the version I heard as a kid ended. So probably the weak sause king ending.

I rather like Stephen Kellogg’s picture book version of the tale. Foxy Loxy, disguised, leads off the fowl to “safety”, only to have CL recognize him and try to warn the others. He locks them up in his truck and sneeringly shows them the acorn (“This is what beaned the brainless chick!”), tossing it in the air–where it gets caught in the rotors of Officer Hefty Hippo’s helicopter. He bails out–and lands right on Foxy Loxy’s truck, breaking the prisoners free and hauling Foxy to the clinker. Chicken Little plants the acorn, which is still around when she tells her grandchildren the tale.

@3. Stephen Kellogg is the best.

“And Foxy Loxy and Mrs. Foxy Loxy and their seven little foxes never forgot the wonderful meal they had that night.”

That’s the ending of the version I grew up with. Heartwarming, right? *snicker*

I grew up on the version in The Stinky Cheese Man, where it’s not the sky but the Table of Contents that actually really falls on everyone’s heads at the end and squashes them. This remains my favorite ending. In some ways I was a rather strange child.

This story isn’t so well-known in Holland; in fact I’ve never seen a Dutch version.

But I’ve always liked the saying that’s used to give a scaremonger a set-down, which really sounds as if it’s based on this story: “And when the heavens come falling down, we’ll all be wearing a blue hat”; i.e. what you’re saying is ridiculous, it will never happen, and if it did the results wouldn’t be as bad as you’re saying (like wearing a nice piece of blue sky for a hat, instead of being killed).

It would be a rather Dutch ending to the story, if all those panicked (farm) animals met up with someone with common sense, like the farmer, who pointed out how ridiculous they were being and made them see sense again, and go back to their lives feeling ashamed of their gullibility/nonsensical fear. As said I’ve never seen the story in Dutch, so I’ve no idea if it used to be known here; and if so, if it might have had an adjusted ending like that. Considering the saying, it seems possible.

In the Asterix comics they always say the only thing the Gauls fear is that the sky will fall on their heads.

The punchline of the WW2 Disney version suggests that they thought the other version was more familiar then:

NARRATOR: Hey, that’s not how the story goes!

FOX: Yeah, well, don’t believe everything you read.

@MariCats, have you seen this idea that was posted on TOR?

http://www.tor.com/2016/05/10/sequel-to-lilo-and-stitch-and-monsters-inc-idea/#comment-588998

I must put my two cents in on the the true story of chicken little is far more complex and older than you think…but it is simple to tell for a reason it is an intentonal historical meme….cicken little gesticulates wildly in every language and says the sky is falling (because it really is people) the vilagers cause him all kinds of grief but eventually believe him and get to work then they fall asleep and for get…. this happens every generation….chicken little is one of the oldest spoken word fables in human lore…so compact in its information it can easily be translated into any language….the sky is falling guys

I have retold this story in a 10 minute animation as a part of my MA in Sequential Design and Illustration. Henny Penny and her companions are made out of found and recycled materials to symbolise their flawed personalities, including murderous Foxy Woxy made out of half gobbled toys:

http://dagmararudkin.com/henny-penny-trailer