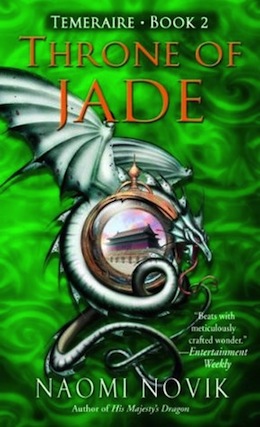

Hello, everyone! Welcome back to the Temeraire Reread, in which I recap and review Naomi Novik’s Temeraire series, one novel a week, leading up to the release of the final volume, League of Dragons, on June 14th. We continue this week with the second novel, Throne of Jade, in which we head for China. You can catch up on past posts at the reread index, or check out Tor.com’s other posts about Naomi Novik’s works through her tag.

Reminder: these posts may contain spoilers through all currently-published novels, but will contain no spoilers for the forthcoming League of Dragons (because I haven’t read it yet). If you have read League, absolutely no spoilers! But there’s no need to warn for spoilers about the published books, so spoil—and comment!—away.

(However, I will have uncertain internet access for several days after this post goes live; I promise to respond to comments as I can, though.)

PART I (Chapters 1-5)

Chapter 1

The novel opens very soon after the close of the first, in November 1805. Prince Yongxing, one of the brothers of the Emperor of China, has arrived to demand that Temeraire be sent to China.

Temeraire is refusing to go, and Laurence is refusing to lie to him to get him out to sea, much to the distress of both governments: the British are desperate to give China no reason to ally with France, while the Chinese are profoundly insulted by Temeraire being in military service—to a mere captain, to boot. At a meeting, an Aerial Corps Admiral sends Laurence away before Barham (the First Lord of the Admiralty) can order him arrested, or before Laurence actually hits someone.

Jane Roland is on liberty in London; she finds Laurence and takes him back to her inn for food and comfort sex. They are woken by the news that the Channel Fleet needs aerial support to attack a French convoy; Laurence goes to the London covert with Jane, to help on the ground.

At the covert, Laurence hears the divine wind and finds that Barham is telling Temeraire that Laurence has taken another dragon. Laurence has been obeying orders to the extent of staying away from Temeraire, but now rushes to Temeraire to stop him from hurting the defenseless humans. When Barham orders Laurence arrested, Temeraire picks Laurence up and carries him away to Dover, toward the battle he overheard Jane speak of.

Chapter 2

During the battle, Laurence’s crew fights off a boarding attack led by a gallant young Frenchman, and Laurence is knocked out by a French dragon’s attack. Laurence wakes to find Barham threatening to shoot Temeraire with a pepper-gun so that he can arrest Laurence. Violence is averted by the dragon-surgeon Keynes, who furiously points out that the commotion is stirring up all the dragons.

The next day, Barham intends to dismiss Laurence from the service and—somehow—send Temeraire to China alone, when an unexpected reprieve comes from Yongxing, who says that if Temeraire will not go without Laurence, then Laurence must go as well. (Barham: “Good God, if you want Laurence, you may damned well have him, and welcome.”)

Arrangements are made for a rapid departure: Admiral Lenton of the Corps sends Laurence’s crew with him, to avoid punishment for defending Laurence and Temeraire, and Laurence informs Riley (his lieutenant in the Navy, currently on shore) that the dragon transport Allegiance needs a captain. Laurence also meets Arthur Hammond, the very young but authoritative diplomat accompanying them. Hammond tells Laurence frankly that the British have no idea why China sent Temeraire’s egg to the French; it’s an act that shakes their foundational belief “that the Chinese were no more interested in the affairs of Europe than we are in the affairs of the penguins.”

Chapter 3

After much difficulty with baggage and manners, the Allegiance puts out to sea. Hammond maneuvers Riley into inviting the Chinese party to dinner, at which it comes out that they had forced four ships from the East India Company to bring them to England without pay. Laurence and Riley manage to keep violence from breaking out, but all of the British sailors and aviators are deeply offended and enraged.

Chapter 4

In the night, the Allegiance is attacked by two French frigates and a Fleur-de-Nuit dragon. Temeraire is at a disadvantage in the dark until the Chinese party supplements the ship’s flares with rockets (fireworks) out of their baggage. The additional light allows Temeraire to drive away the Fleur-de-Nuit, get his crew on board, and attack the French frigates with the divine wind. Unexpectedly, the wind causes a tremendous wave; the combination of the two tips one of the frigates over, sinking her entirely.

Temeraire was shot during his attack, but Lily’s formation had been doing exercises not too far away, and its arrival causes the other frigate to surrender.

Chapter 5

Everyone is unsettled by the British deaths in the battle, including that of ten-year-old runner Morgan, and by the almost eerie sinking of the French frigate. Yongxing is livid that Temeraire was injured and intends to set guards around Temeraire to keep Laurence and his crew away; Laurence responds by forbidding them access to the dragondeck. Despite this, Hammond manipulates an unknowing Riley into giving the Chinese party permission to walk the dragondeck. Laurence abhors Hammond’s behavior, which he views as tactless, single-minded seeking of diplomatic advantage; Hammond points out that humiliating Yongxing at sea will only make things worse on land.

Lily’s formation leaves on another transport, which is also carrying a dragon from an Indian tribe in Canada, exchanged from the breeding grounds for Praecursoris.

Commentary

There are two exciting air battles in this first part, which I have given short shrift because ultimately what’s more important for these purposes is all the setup.

Shall we do minor things first? On a reread, that dragon from North America ought to be introduced with a “dun dun dunnnh” sound effect: the illness he brings will set in motion much of the conflict of later books, and be the first alternate-history example of what academics call the Columbian Exchange. (A great popular-level read on the topic is 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created, by Charles C. Mann, who also wrote 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. I recommend them both highly—extremely readable, entertaining, and even-handed treatments of very important research. Seriously, if you’re reading this post you will like those, go check them out.)

Back in England, there was this very succinct comment from Admiral Lenton about the difficulty the non-Corps military has dealing with dragons: “If we ever manage to get it into their heads that dragons are not brute beasts, they start to imagine that they are just like men, and can be put under regular military discipline.” And that’s one of the ongoing struggles depicted in the series: are dragons just like humans? Can they, or should they, be treated the same way? Or, perhaps, should they all expect better treatment? (Note that later in this part, there’s a brief mention of abolitionists in Parliament gearing up for another push soon, to remind us that slavery is A Thing.)

As for the Chinese embassy: Yongxing is indeed the name of a son of the previous (Qianlong) Emperor, but by an Imperial Noble Consort rather than an Empress, which makes it doubtful that he could have been Emperor (as is stated in Chapter 12); so this Yongxing should probably be viewed as fictional. We also briefly meet Sun Kai and Liu Bao, who will both play more prominent roles in the next books. Otherwise, to me, the main effect of this part is to build the tension and the difficulty: Yongxing is implacably opposed to Temeraire and Laurence’s relationship, everyone but Hammond hates the Chinese embassy, Laurence and Hammond are getting along very poorly, and Temeraire and Laurence are both missing their friends and recovering from injury.

I am not convinced that the pacing of this novel is optimal; more about that later, but my first reaction, looking over this summary, is that the second battle might reasonably have been excised (though I admit that it sets the precedent for Lien’s destruction of the British fleet at the end of Victory of Eagles).

PART II (Chapters 6-10)

Chapter 6

The journey presents many problems. Laurence manages to make a friendly acquaintance in Liu Bao by offering him some ship’s biscuit as a remedy for seasickness. But the contact with Liu Bao exposes Temeraire to the concept of Chinese poetry written by dragons, and Prince Yongxing jumps at the opportunity to further Temeraire’s knowledge of Chinese (Temeraire remembers some from the shell; Laurence doesn’t know enough to convey which dialect). Laurence is worried and jealous, though Temeraire works hard to include him in conversations.

Because Temeraire is still healing from the battle, he cannot catch fish for his meals. This raises the prospect of stopping as a slave port to resupply, a fraught matter because Laurence is an abolitionist whose father once specifically attacked Riley’s slave-owning father in Parliament, an act that offended Riley, who actually likes his father.

Finally, the sailors fear Temeraire and resent the aviators for doing less work. This boils over in the form of one of the aviators, Blythe, striking a midshipman—to prevent the midshipman from challenging an aviator officer to a duel, because dueling is forbidden by the Corps, but Laurence will still have to allow Blythe to be flogged.

Chapter 7

Temeraire is deeply distressed by Blythe’s flogging and by seeing captives being driven into a slave ship; Laurence’s explanations only deepen the coldness between him and Riley that arose after Blythe’s punishment. The mood aboard ship worsens when they learn of the stunning French victory at Austerlitz, which broke the coalition against Napoleon. They briefly debate turning back, but Hammond impresses upon them the need to protect Britain’s trade in the East so that they can supply their allies on the Continent.

Temeraire, frustrated at everything and particularly at not being able to fly, takes it upon himself to go swimming, which at least is successful. But Temeraire’s good mood seems to prompt Yongxing to speak frankly to Laurence: he promises that China will not go to war with Britain or its allies, if Laurence will encourage Temeraire’s return to China. Reflexively, Laurence refuses, which Hammond actually approves of from a negotiating stance: “how much more progress may we not hope to make?”

This depresses Laurence more, because it seems that “a truly advantageous treaty” might be possible after all, and then it would be his duty to separate from Temeraire. To top it all off, as they leave Cape Coast, they see a slave revolt brutally suppressed.

Chapter 8

The tension between the sailors and aviators is slightly broken by the ceremony of crossing the equator and the resulting invitation to a feast celebrating the Chinese New Year. The mood is further improved by the news that the British have taken the Dutch settlement at Capetown; this comes via the courier dragon Volly, who also brings a terrible cold and greetings from their formation, whose dragons miss Temeraire because he taught them how to open the feeding pen at Dover.

At the feast, Sun Kai prompts Laurence to write down the history of his family’s title and connection to the English monarchy (“he had to leave several given names blank, marking them with interrogatives, before finally reaching Edward III after several contortions and one leap through the Salic line”). Temeraire also enjoys feast dishes from the Chinese cooks.

After the feast, Laurence is struck on the back by Feng Li, a servant of Yongxing; Laurence assumes automatically that Feng Li lost his footing on the deck.

Chapter 9

In Capetown, Temeraire continues to suffer a reduced appetite from the cold he caught from Volly. Laurence swallows his pride and asks Yongxing if the Chinese cooks would make more flavorful dishes for Temeraire; Yongxing agrees with alacrity and more courtesy than usual. The Chinese cooks, encouraged by Temeraire’s positive reaction, urge the local children to bring them increasingly-bizarre ingredients, which culminates in “a misshapen and overgrown fungus … so fetid” that the five children who found it “carried it with faces averted.” Temeraire enjoys it and is much improved afterward.

The Allegiance leaves Capetown. During a storm, Feng Li attacks Laurence, but is washed overboard. Laurence is too numb from the storm to take action initially; after, he reluctantly agrees with Hammond that no good can come of accusing Yongxing.

Chapter 10

The ship hunts many seals at New Amsterdam; the resulting butchering attracts an enormous sea-serpent, which comes close to crushing the ship in its coils before Temeraire kills it. He is very distressed at having to do so, though to Laurence “the lack of sentience in the creature’s eyes had been wholly obvious.” It develops that Temeraire has been pondering obedience to orders, slavery, and his dependence on Laurence, and fears that dragons are no better than slaves. Laurence eventually admits that it is unfair that dragons’ movements are restricted by humans’ fears, and promises Temeraire that “whatever inconveniences society may impose upon you, I would no more consider you a slave than myself, and I will always be glad to serve you in overcoming these as I may.”

Commentary

Less in the way of exciting action, more in the way of pervasive unhappiness; I hardly require that every page of every novel be unalloyed cheer, that would not serve in the least, but I do think this middle part, which is all voyage, could have stood to be trimmed.

Things that are setup for the rest of the novel: the ongoing lack of sympathy between Laurence and Hammond; Laurence’s ancestry, which will give him unexpected status in China; and Feng Li’s murder attempts. Things that are setup for the rest of the series: the fungus that cures Temeraire’s illness; Temeraire’s continuing and deepening concern over the status of dragons; the giant sea-serpent (I’ll have to compare descriptions when we get to the ones used for transport in Tongues of Serpents); and the topics of slavery and Africa, including a bit that I didn’t summarize from Chapter 8, when Laurence and Temeraire take a long flight inland over Africa, over the “unchanging jungle”: Laurence tells Temeraire that “Even the most powerful tribes live only along the coasts … ; there are too many feral dragons and other beasts, too savage to confront.”

I will have more to say about the differing factions in China when we get there, but it’s worth noting that Prince Yongxing gives a long speech in Chapter 7 explaining his position:

“We do not desire anything that is yours, or to come and force our ways upon you,” Yongxing said. “From your small island you come to our country, and out of kindness you are allowed to buy our tea and silk and porcelain, which you so passionately desire. But still you are not content; you forever demand more and more, while your missionaries try to spread your foreign religion and your merchants smuggle opium in defiance of the law. We do not need your trinkets, your clockworks and lamps and guns; our land is sufficient unto itself. In so unequal a position, you should show threefold gratitude and submission to the Emperor, and instead you offer one insult heaped on another. Too long already has this disrespect been tolerated.”

And now, China, finally!

PART III (Chapters 11-17)

Chapter 11

On June 16, 1806, the Allegiance arrives at Macao (a Portuguese settlement in mainland China, near Hong Kong) and waits for instructions from the Emperor. Laurence is shocked when those instructions arrive from Peking (Beijing), two thousand miles away, just three days after their arrival.

In the interim, Laurence and Hammond had met with commissioners of the East India Company, who see their arrival as the opportunity to retaliate against the Chinese government for seizing the Company’s ships. In the resulting lengthy discussion, Laurence sees that Hammond and the commissioners disagree on almost everything, which further undermines his confidence in Hammond.

They depart rapidly, in obedience to the Emperor’s word, taking ten members of Temeraire’s crew plus the remaining runners, Roland and Dyer (at the suggestion of Staunton, one of the Company commissioners). Laurence also arranges for the Allegiance to follow as soon as it is resupplied, so that they have an escape mechanism (and he has Staunton’s advice).

Chapter 12

As the reduced party journeys to Peking, Laurence notes the immensity of the country and the density of its population—human and dragon—and fends off attempts to physically separate him from Temeraire.

On the way, they meet Lien, a Celestial who is companion to Yongxing. Her “shockingly pure white” scales are the color of mourning and therefore she is considered unlucky; Liu Bao explains that Yongxing refused to let the Qianlong Emperor send her to a prince in Mongolia, which disqualified him from the throne.

They arrive in Peking and a standoff regarding etiquette is interrupted by Qian, Temeraire’s mother.

Chapter 13

At a welcome feast, Laurence meets De Guignes, the charming French ambassador, and coincidentally the uncle of the gallant young Frenchman who led the boarding attempt of Temeraire in Chapter 2.

The next day, Laurence and Temeraire explore Peking. They learn that army dragons have only women for companions, which developed from (1) a version of the story of Mulan and (2) families’ preference to send girls to the army in times of conscription. Moreover, all dragons wait until they are 15 months old to choose companions, and are raised and taught by other dragons until then. The city itself was clearly designed for dragons and humans to live and work together: they see dragons acting as transport, dragons in the civil service, dragons with and without human companions, all “engaged in many errands.” Laurence admits to Temeraire that he was mistaken, and that “plainly” humans “can be accustomed” to the close presence of dragons. Laurence also buys a number of items, including a beautiful red vase.

Back at the pavilion, Sun Kai brings an invitation for Laurence and Temeraire from Qian, Temeraire’s mother, and strongly hints that her good opinion is important. As a result, in private conversation with Qian, Laurence swallows his pride and “puff[s] of his consequence” when a servant brings out a copy of the family tree he made at the Chinese New Year feast. Qian stuns Laurence when she says that Celestials do not breed among themselves, only with Imperials, and that there are only eight Celestials left in the world, of whom she and Lien are the only females. (Two Imperials do occasionally give birth to Celestials.) The rest of the British are also stunned, both regarding the risk of extinction and because they are even more baffled as to why the Chinese sent Temeraire’s egg away.

Chapter 14

Laurence gives Temeraire leave to visit Qian alone, which Laurence finds upsetting both because he worries that Temeraire will want to stay and because Hammond disapproves. Yongxing brings a plainly-dressed adolescent boy to visit Temeraire in an entirely transparent attempt to supplant Laurence; the boy and Temeraire aren’t interested in each other, but Laurence and Hammond fight even more over how to handle it.

On Laurence’s orders, Yongxing and the boy are denied access to Temeraire the next day. That afternoon, after Temeraire goes to visit Qian, Sun Kai wakes Laurence and tells him, in perfect English, “Come with me if you want to live”—okay, actually he says, “You must come with me at once: men are coming here to kill you, and all your companions also,” but close enough. Laurence is shocked that Sun Kai can speak English, and does not trust him enough to put them all in his power; he points out to Hammond that this could be an attempt to separate them from Temeraire, who should return within a few hours. Sun Kai leaves, and Hammond stays.

The British barricade themselves in the pavilion and fight off approximately a hundred brigands, in multiple waves lasting all night. Everyone fights and kills, including the young runners and Hammond. One of the aviators is killed, and several are seriously wounded, but the attackers finally flee after enormous casualties. At the end of the chapter, Laurence surveys the scene: “There was no sign of Temeraire. He had not come.”

Chapter 15

Shortly after the end of the attack, Sun Kai finds them “half-blind and numb with exhaustion,” and takes them to Prince Mianning, the crown prince. That evening, Temeraire returns, distressed and guilty; he had lost track of time because he was “with Mei,” a female Imperial dragon.

Temeraire explains that Mianning is companion to his older twin, Chuan. Hammond realizes that Temeraire’s egg was sent away to avoid setting up a rival for the throne, meaning that there is no alliance with France and that Mianning has every motivation to see Temeraire leave again.

They recover from the attack, and Temeraire continues his education and his courting of Mei. They are invited to dinner by Liu Bao, who tells Laurence that no one can stop Temeraire from continuing to be his companion, and casually suggests, “Why doesn’t the Emperor adopt you? That would save face for everyone.” Hammond seizes on the idea enthusiastically, and Laurence reluctantly agrees.

Chapter 16

The Allegiance arrives with Granby and Staunton of the East India Company; they had helped a Chinese fleet defeat “an enormous band of pirates,” including dragons. At a theatrical performance given to honor the new arrivals, they see the boy who Prince Yongxing introduced to Temeraire—Prince Miankai, the Crown Prince’s younger brother.

“Laurence,” Hammond said, “I must beg your pardon; you were perfectly right. Plainly Yongxing did mean to make the boy Temeraire’s companion in your place, and now at last I understand why: he must mean to put the boy on the throne, somehow, and establish himself as regent.”

“Is the Emperor ill, or an old man?” Laurence said, puzzled.

“No,” Staunton said meaningfully. “Not in the least.”

Temeraire, already angry at hearing this, becomes murderous when an assassin strikes Laurence with a thrown dagger; he quickly kills the assassin and then stalks toward Yongxing, who Lien intervenes to protect. In the resulting fight, Temeraire’s greater experience is giving him an advantage; but the dragons destroy the wooden stage, which “burst[s] into foot-long shards of wood.” Laurence saves Mianning’s life by knocking him out of the way; Yongxing is killed instantly. Lien retreats from the fight, gathers Yongxing’s body, and flies away.

Chapter 17

Laurence is formally adopted by the Emperor and granted an estate, giving the British the equivalent of an embassy (Hammond will stay there). He and Temeraire are also officially bound as companions.

Afterward, they see Lien walking with a man (revealed next book to be De Guignes). Laurence asks Temeraire if he would like them to stay in China, which Hammond and Staunton both suggested. He tells Temeraire that while he would prefer to go home, “I would rather see you happy; and I cannot think how I could make you so in England, now you have seen how dragons are treated here.” Temeraire ponders this and concludes, “I could not be happy while I knew Maximus and Lily were still being treated so badly. It seems to me my duty to go back and arrange things better there.” Laurence is initially taken aback, but then agrees.

They end the book contemplating poetry and the tides, respectively.

Supplementary Material

This book includes more excerpts from the writings of Sir Edward Howe, the naturalist we met in the first book. It mentions that John Saris visited Japan in 1613 and that the Sui-Riu breed had the “capacity to swallow massive quantities of water and expel them in violent gusts, a gift which renders it inexpressibly valuable not only in battle, but in the protection of the wooden buildings of Japan from the dangers of fire.”

Sir Edward describes something of how dragons function in Chinese society: there is a Ministry of Draconic Affairs to handle food supplies (helped by using dragon dung as fertilizer, which permits a yield “an order of magnitude” more than that of British farms). He also explains how the financial system works: dragons pay by leaving their mark for merchants to redeem from their accounts, never defraud humans (by their standards, anyway), and never suffer themselves to be defrauded: “Chinese law expressly waives any penalty for a dragon who kills a man proven guilty of such a theft [from their accounts]; the ordinary sentence is indeed the exposure of the perpetrator to the dragon.”

Commentary

So much to talk about! I know it’s a three-volume structure, but I remain unconvinced that leaving China for the third volume was optimal, because there’s just so much potential to explore there.

Let’s start with alternate history and the denouement. My opinion of this has changed over time, as I learned more about Chinese history. When I didn’t know much, I remembered thinking that it was awfully convenient that the “good” faction was the one that advocated interaction with the West; I had a vague sense that such interaction had been pretty lousy for China and thought that Yongxing had a point in the big speech I quoted above, though not to the point of murderous conspiracies, of course.

Then I read the relevant parts of the brick China: A New History, by John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman, in preparation for this project. (I recommend it, though like I said: brick.) That book described the treaties that China signed starting in the 1840s, which were literally a byword for inequality (here’s Encyclopædia Britannica and Wikipedia on the topic). Fairbank calls “the social disruption and psychological demoralization caused by foreign imperialism….… a disaster so comprehensive and appalling that we are still incapable of fully describing it” (Chapter 9). So from this slightly more knowledgeable perspective, it seemed that this AU provided China with reasons to choose to engage with Western nations earlier, plus a better position when it did, which I presume (or at least hope) will thereby allow it to avoid the Century of Humiliation. And since I really enjoy the way this series says “Dragons are awesome! Let’s see how many ways they can make the 19th century suck less,” I’m glad to add this to the list. (However, I am painfully aware that reading one book, even if it is a giant and well-respected one, still leaves me far short of expertise, and I would very much like to hear the thoughts of those more knowledgeable.)

It’s a matter of opinion how much of this historical divergence and its significance the book should convey. There’s an argument that fiction is written for an assumed audience that probably knows about X and Y, but maybe less about Z, and so an author should take that into account when writing about Z. There’s also an argument that readers are perfectly capable of inferring worldbuilding and/or doing research when reading fiction about X, Y, or Z, and that there’s something to be said for treating X, Y, and Z on equal footing. I generally prefer the second approach; my only hesitation here is that I don’t know how well the full effect of the series comes across if people don’t have the context and don’t seek it out.

(There are some passing references that I can’t match up precisely, either because of my own research failure or because they’re alternate history. In Chapter 11, Laurence hears Hammond and the commissioners talk of “some local unrest among the peasants and the state of affairs in Thibet, where apparently some sort of outright rebellion was in progress; the trade deficit and the necessity of opening more Chinese markets; difficulties with the Inca over the South American route.” Obviously the bit about the Inca is alternate history, and “local unrest” could be anything; but I haven’t found anything about a rebellion in Tibet in 1806, and suppressing the pirates in the Zhoushan Islands (Chapter 16) happened centuries earlier in our history.)

Okay, let’s shift gears. Dragons! How cool are all the different ways that dragons are full members of Chinese society? I loved that so much when I first read it. (I still love it, it just takes up less of my attention now that it’s familiar; one of the perils of rereading.) Such fun SFF worldbuilding. I do wish we knew what oaths dragons and humans take when they’re formally bound as companions, though. And of course Temeraire is now set on the path of the reformer.

A friend of mine once noted that Temeraire is a third culture kid, someone who spends significant time during their developmental years in a culture that’s not their parents’, and who must negotiate a cultural identity in light of these first two cultures. We see this in the series in Temeraire’s determination to adapt Chinese practices to British life, and the relationships he will maintain with his mother and Mei. (I should put this somewhere for reference, and here’s as good as any: Temeraire’s birth name was Lung Tien Xiang; the Temeraire wiki has details on the characters used and some transliteration issues.)

We also get a few more tidbits about dragon breeds. I’d forgotten about the extreme rarity of Celestials, but that’s a problem that, potentially, Temeraire and Iskierka have solved. (I haven’t read the last book yet, so I don’t know if their egg hatches successfully. Also, I have no idea what it will do to the international balance of commercial and political power if suddenly China starts seeking many Kaziliks.) I also liked the note that female dragons are generally not maternal after hatching (Granby: “Not that they don’t care at all, but after all, a dragonet can take the head off a goat five minutes after it breaks the shell; they don’t need mothering.”). Between dragon mothers and Jane Roland, we get a portrait of caring but hands-off motherhood, which is somewhat unusual and thereby refreshing.

The question of roles for women otherwise is not a focus of this book. We are told early that Harcourt has been given command of the formation (and her age, which is twenty), and Riley discovers that Emily is female, which will prepare him to meet Harcourt later. And, as I mentioned in the summary, all army dragons have women as companions.

The two major new characters introduced by this book are Lien, who is a fabulous antagonist [*], and Hammond, who is knowledgeable, correct about many things, and unexpectedly brave, but, possibly, could stand to employ diplomacy on those of his own country … ? I don’t recall getting very excited when we meet up with Hammond again, but we’ll see. As for Lien, I think I would regret the waste if she ended the series dead, but it’s hard to imagine that she might accept defeat short of that. *valiantly suppresses urge to spoil self with review copy*

[*] I should mention the Evil Albino stereotype. I feel that because the series shows that Lien acts from loyalty to the one person who didn’t ostracize her for her color, it avoids the most harmful parts of this stereotype; but this is not an issue that hits me where I live, so I’m even more aware than usual that opinions may reasonably vary.

Last little note: I love it when fiction manages to convey to the readers something that the characters don’t know. It happens here in Chapters 11 and 12; first Laurence writes to Jane and tells her that Keynes, the dragon surgeon, thinks the aviators largely escaped malaria because “the heat of his body in some wise dispels the Miasmas which cause the ague,” and then Laurence notes that “mosquitos … evidently did not care for the dry heat given off by a dragon’s body.” Hah! Miasmas indeed. (I hate mosquitoes, because their bites make me swell up enormously; just another reason to wish for my own dragon!)

Be thoughtful and courteous in the comments, and I’ll check in when I can; and I’ll definitely be here next week for Black Powder War.

Kate Nepveu was born in South Korea and grew up in New England. She now lives in upstate New York where she is practicing law, raising a family, running Con or Bust, and (in theory) writing at Dreamwidth and her booklog.

In the (unlikely) event that you were not aware, De Guignes is another of those characters plucked out of “real” history.

Speaking only for myself, I’m inclined to give Novik the benefit of the doubt when it comes to the whole “Evil Albino” thing. Of course, I have first-hand experience with the whole “White is the color of mourning” thing, being Asian-American in the corporeal world. YMMV, as we like to say.

slvstrChung, it didn’t occur to me to check his historicity, thanks! And yes, I know about the color of mourning (and the text explains too), and like I said, I’m good with it, but it was something I thought about in a way I should discuss here!

Its and odd thing to focus on, but it always annoys be a little to see the “Poor Communication Kills” trope show up. The idea that the British and Chinese delegations shouldn’t trust each other, holding back information? Completely valid and vital. The whole piece about the fact that aviators can’t dual because of their dragon’s bonding being damaged, though, shouldn’t be a secret. After all, all the dragons and aviators know it (that’s why capturing a Captain is such a big deal), and it doesn’t benefit the aviators at all to keep that all mystical and shrouded in secrecy from their own Navy (who presumably also know about things like capturing captains). It does add tension though, I’ll give it that.

I love how so many characters we meet in the first few books pop up later on in the series. Also Granby has to be one of my favorite characters, along with his dragon later on Iskierka. Iskierka definitely spices things up!

Thanks for the link with the short story of Temeraire and the feeding pen, I didnt know that was available.

Keynes is one of the best in these early books. Nobody get in the surgeon’s way, he stitches up three ton flying war machines for a living and isn’t going to be deterred by someone who just wants to arrest someone.

I love the humor we get from our obstinate bit characters everywhere. And the fact that this book sets up so much for the future books: not only the plague, which will keep having ramifications throughout the whole series, but also going into the southern Atlantic for the first time and emerging into global concerns, instead of just Europe’s Napoleonic problems.

A thing that I notice a bit more now that I’ve read through the whole series: Lawrence starts out very willing to trust everyone else’s opinions on what is the right and most honorable thing to do, what with his “agree to never speak of it because it’s too political,” arrangement with Riley on the subject of slavery, his willingness in the first book to be parted from Temeraire so that he can be given to a trained aviator, and the catalyst of all his character growth in the early series, his openness to learning from the other aviators and now from the more friendly Chinese how best to take care of Temeraire. He doesn’t loose it until the end of book four, but it certainly lays the groundwork for his relative flexibility in terms of other cultures, and Temeraire’s ideals, in the later books.

to Laurence “the lack of sentience in the creature’s eyes had been wholly obvious.”

One thing that does raise questions later on (in Tongues of Serpents – the Austrailia book) is that sea serpents are pretty clearly trainable, but not seemingly considered by the Chinese (and later Japanese) dragons as anything like dragons themselves. They don’t seem to either have a language or be capable of truly learning one, and unlike dragons they appear to have very little in the way of cooperative abilities… but they must be fairly closely related to dragons somehow. One wonders what drove such divergent evolution. And how there are enough whales in the ocean to feed these serpents what with all the whaling that was going on in this era… maybe they also eat squid.

I’d forgotten how little time the book actually spends in China on the attempted murders of Temeraire’s crew. And how blatantly obvious the attempts would be if anyone knew both the culture and the language…

Granby: “Not that they don’t care at all, but after all, a dragonet can take the head off a goat five minutes after it breaks the shell; they don’t need mothering.”

Considering how much Iskierka needs some restraint taught to her and how bad Granby is at this early on, I find this amusing. I can’t help but think an enormous dragon like Lily or Mei would have made a deeper impression on her, er, youthful enthusiasm. :)

In regards to Lien: I have nothing but sympathy for her in the context of this book. Of course, we don’t know how involved she was in the assassination plot, but in regards to making her chosen companion happy, she has the exact same motivation as every other dragon in the series. The fact that her own culture considers her unlucky and that her companion chose her even though he knew it would get him disqualified as heir obviously makes her motivation rather stronger than we see in other dragons, especially the Incan ones, who don’t pick favorites. It also makes her a very good foil for Temeraire: both of them have lives shaped by the imperial family’s little dynastic game here, and to be quite honest Temeraire’s generous personality isn’t entirely caused by growing up on honor and duty with Captain Lawrence. He has the opportunity all his life to make friends with, and be respected by, other dragons, and Lien is denied it even when she becomes companion to Napoleon, as it’s rather hard to make friends with the French dragons when she’s installed as their superior.

One interesting detail is how the fact that only eight Celestials exists is considered a big deal by the British. Considering how few dragons Britain or even France have, I doubt some of the rarer breeds number much higher.

@6 I think its mentioned later on that are around a hundred dragons in England, but most of those are retired or unharnessed in the breeding grounds. Again I welcome correction, but I think the common way of describing England’s lack of dragons is how many they can bring to a fight.

I think we are misdirected by recurring characters into believing their are far fewer than there are. I seem to remember scenes where Laurence is among several dragon captains he is unfamiliar with. Perhaps this is to spare us the names of one time characters, but if there were only the dozen dragons we see over and over and a few others, I don’t know how this could be unless there are some amount more than we are shown. Of course, after books 3 and 4, who knows how many are left. I can’t remember how many were named deceased

————–

@Kate

I still struggle to understand why I like Lien as a villain. She doesn’t say ANYTHING in book 2 (I suppose that adds to her coolness factor). Everything she says in the rest of the series could probably fit on a single page. She doesn’t even appear all that often. What, three times in book 3, once at the end of book 4, twice in book 5, then once in book 7. And entirely absent from books 6 and 8.

I mean, she’s an awesome foil for Temeraire, but it doesn’t seem like she’s really done anything all that terrible beyond her dramatic escape in book 5. I suppose she improved Napoleon’s army on the whole, which is bad. And helped turn some key people against England. The Sultan? in book 3 and the Empress? in book 6.

It seems to be suggested by the summary for book 9 that she might still have influence in China and might have been behind some of the difficulties Temeraire has in book 8. I suppose that is my problem. She isn’t what you expect from a major villain, she isn’t dramatic or destructive, but is a very behind the scenes and restrained sort of antagonist.

Also…

I noticed something while rereading this book that I hadn’t before. We see an interesting comparison in viewpoint as Temeraire kidnaps Laurence.

[“Temeraire, they cannot let us fight; Lenton will have to order me back, and if I disobey he will arrest me just as quick as Barham, I assure you.”

“I do not believe Obversaria’s admiral will arrest you,” Temeraire said.]

There are several things one could say about this exchange. The first is Temeraire views Lenton as the other dragon’s property. He could have said “Obversaria or Lenton” stating the dragon foremost, but we don’t even get that. Lenton is solely hers, which is even more odd by the mention that even though Lenton is her property, Lenton is the one who will decide. He does seemingly suggest that she might be able to convince him when he continues to say:

[“She is very nice, and has always spoken to me kindly, even though she is so much older, and the flag-dragon.]

Or perhaps this means she is nice, so her handler must be as well. I can’t say. Of course we see this possessiveness a lot in further books. To the point of dragon pricing humans.

The other interesting bit is that he say’s “admiral” instead of just captain or something more generic. This could be taken at face value, that Lenton is her captain and an admiral, but feels like a show of regard or rank. That she’s important because she has an admiral, while everyone else only have captains. I suspect Temeraire wouldn’t mind having an admiral too.

I can’t help but find this amusing as if dragons invest in people like people invest in gold, hoping they rise in value over time. True, people do this as well, following someone who might carry them on to higher status. But I can’t help but imagine a dragon who appraises humans.

“Your captain is worth thirty cows.”

“But my captain is an admiral!”

“Oh, then I suppose he is worth forty cows.”

We see a little of this with Granby in book 7. “I don’t want to marry the Empress!” “Why ever not?”

@Jerrico

Jane Roland makes an offhand comment on having to feed two-hundred dragons in Empire of Ivory. That may or may not include dragons in the breeding grounds, or those outside of Britain (i.e. those stationed elsewhere in the empire or at various outposts). I’m inclined to believe that at least includes the dragons in the breeding grounds within the British Isles, as I doubt Roland would want to see them die, whether they could fight or not. Also, she makes another comment towards the end of the book that the French can’t have more than two hundred fighting dragons even though they clearly do, foreshadowing the use of feral dragons by the French.

Of course, the books aren’t always consistent on this. For example, several characters in Victory of the Eagles mention how the plague might have killed ten thousand dragons. I suppose that could refer to the dragon population in Europe, though I’m not sure such a number is feasible. However, Wellesley makes a comment towards the end that he won’t see ten thousand beasts stirred up by Temeraire, indicating that Britain has that many? Laurence also states in the next book that thousands of French dragons alone would have been killed by the plague, even though in the previous book he predicted that France could have a fighting force of one thousand dragons soon, indicating it doesn’t yet.

Considering that a dragon Temeraire’s weight is supposed to eat around 200 cattle a year (Wellesley states that feeding him would cost 2000 pounds, and cows are supposed to be 10 pounds), I’m not sure France or Britain could feed a few thousand dragons without severely affecting the human population. That actually seems to be the case in China, but nor in Europe.

The first volume hooked me with the Outsider Protagonist’s Magical Bond with the Fantastic Creature who turns out to be even more special than the Other Fantastic Creatures, but what bit of maturity I possess would have been unsatisfied if the consequences of such an event were not acknowledged in the real (heh) world. Now we find out it’s going to be much worse than being snubbed at a few garden parties.

I misremembered the introduction of the curative mushroom, for some reason I thought it came later in the series; something about caves in Empire of Ivory? But worse is that you quoted the book:

“a misshapen and overgrown fungus … so fetid” that the five children who found it “carried it with faces averted.”

… and thanks to my exposure to the Tor reread of Lovecraft, I am now seeing dragons versus Cthulhu.

Good discussion. Hysterical when Temeraire kidnapped Laurence at the beginning. I love this series. Adore the way this dragon is such a mix of wisdom, dignity, and childish possessiveness and materialism. Cannot wait for the final episode.

I brush up on my history a bit with each book, to see how much of the story is speculative / alternative, and how much is grounded in history. Mostly just Wikipedia. The corrupt Lords of the Admiralty is one of those themes that appears in numerous novels.

It happens that Throne of Jade didn’t wow me until I’d read the entire series and — months later — did a quick re-read of each book. Then I realized how much was set in place here in this book, including the cure for the upcoming draconian plague — which led to so much in books 4-5. Then of course the ongoing conflict with Lien the Celestial begins here and continues, to varying extent, throughout. Also the Emperor’s trading connections in book 6, Tongue of Serpents, and the white lotus plot in book 8, Blood of Tyrants.

Hi everyone, thanks for the comments while I was away!

RJStanford @@@@@ #3, I can buy the “poor communication” thing regarding aviators & prohibited dueling; recall that even Riley thinks that Harcourt could just . . . stop being Lily’s captain (when she’s pregnant and he wants to marry her in Empire), and he’s seen aviators at closer range and for longer than many. So I think that people would just not believe that aviators can’t risk themselves, and it would harm their reputations even more to be putting out so-called flimsy excuses.

radiantflower @@@@@ #4, glad to provide you with the link to the story! It’s interesting to see Novik working out Temeraire’s POV prior to Victory of Eagles.

Quill @@@@@ #5, “obstinate bit characters everywhere” is the name of my next album. => Re: theories of evolution and sea serpents & dragons, perhaps they’re an example of convergent evolution, like sharks and dolphins? And those are lovely points about Lien, thanks.

dadler @@@@@ #6, #8, Jerrico @@@@@ #7 re: dragon population; chapter 1 of Victory of Eagles says, “it did not mean anything to [the retired dragons in the breeding grounds] that dragons in France had also been ill, or that the disease would have spread, killing thousands, if Temeraire and Laurence had not taken over the cure”; and chapter 3 likewise refers to 10,000 dragons “most of them wholly uninvolved in the war”. There are not thousands in the British army, since Wellesley is skeptical of the idea that China has thousands in its army and Laurence tells him that France will soon be able to field a thousand (Chapter 9 of VoE). The battle at the end of VoE (Chapter 16) involved “two hundred thousand men, three hundred dragons, and two dozen ships-of-the-line”, which from context includes the French dragons. So I think the 10k number is Wellington exaggerating for effect.

Jerrico @@@@@ #7, re: Lien: well, she gets an AWESOME chilling speech in the next book, but to me as an antagonist her power is in (1) vastly increasing Napoleon’s already-considerable military effectiveness and (2) bringing a personal edge to the conflict that Napoleon lacks. So she sharpens what’s already there and adds a further element of unpredictability.

Zhaanyatta @@@@@ #9, they go back to get the mushroom in Empire of Ivory, and oh no, I hadn’t thought about Cthulhu at all!

skipper @@@@@ #10, yes, the long-term plotting here is pretty great (I’m actually writing about that in the draft post for book 4 right now!)

Long-term planning is sometimes lacking in long series. It reflects an initial confidence that the series will continue, or maybe just a determination to do it right and plan for success — no matter what. Will look forward to your article on book 4. You are ahead of the game, I’d say!

@katenepveu

I mentioned some of those numbers in my comments, and I could find plenty of other references to the number of dragons if I sat down for a while. My point is that you could find numbers supporting both models of dragon population. It doesn’t help that Novik can be inconsistent even with regards to the same event. For instance, Napoleon supposedly invaded England with 200 dragons, though he was forced to send some back. Wellesley states that with the dragons from the breeding grounds Britain will have some 150 fighting beasts, so I’m assuming that most of both forces fought at the Battle of Shoeburyness, accounting for the 300 dragons. Yet in Blood of Tyrants, Granby states that the British had only 60 dragons, while Napoleon came over with more than 100.

@skipper

The planning is especially impressive considering that these books were commissioned by Novik’s publisher. They apparently liked His Majesty’s Dragon so much that they asked her to write the next two in order to publish all three at once. That’s probably why the first book basically sets up the sequel at the last second, but afterwards the series becomes great at setting up future events for the series.

@13 dadler,

Good to know! That was an 11th-hour sequel-set-up but it felt like it belonged okay there, in book 1.

dadler @@@@@ #13, thanks for the additional numbers–I’ll keep an eye out later!