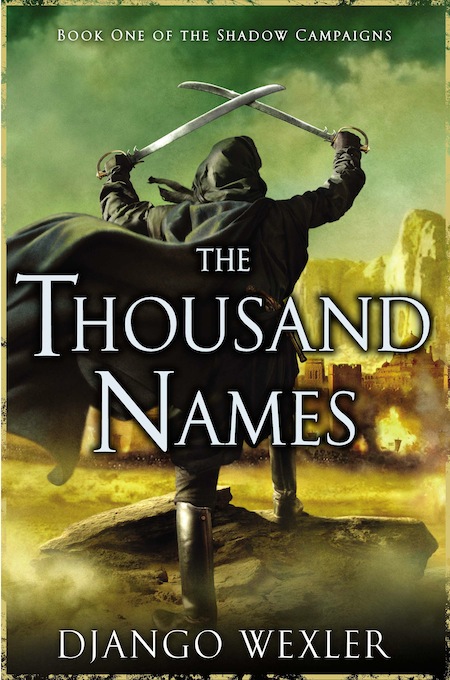

Check out Django Wexler’s The Thousand Names, Book One of the Shadow Campaigns!

Captain Marcus d’Ivoire, commander of one of the Vordanai empire’s colonial garrisons, was resigned to serving out his days in a sleepy, remote outpost. But that was before a rebellion upended his life. And once the powder smoke settled, he was left in charge of a demoralized force clinging tenuously to a small fortress at the edge of the desert.

To flee from her past, Winter Ihernglass masqueraded as a man and enlisted as a ranker in the Vordanai Colonials, hoping only to avoid notice. But when chance sees her promoted to command, she must win the hearts of her men and lead them into battle against impossible odds.

The fates of both these soldiers and all the men they lead depend on the newly arrived Colonel Janus bet Vhalnich, who has been sent by the ailing king to restore order. His military genius seems to know no bounds, and under his command, Marcus and Winter can feel the tide turning. But their allegiance will be tested as they begin to suspect that the enigmatic Janus’s ambitions extend beyond the battlefield and into the realm of the supernatural?a realm with the power to ignite a meteoric rise, reshape the known world, and change the lives of everyone in its path.

Chapter One

Winter

Four soldiers sat atop the ancient sandstone walls of a fortress on the sun-blasted Khandarai coast.

That they were soldiers was apparent only by the muskets that leaned against the parapet, as they had long ago discarded anything resembling a uniform. They wore trousers that, on close inspection, might once have been a deep royal blue, but the relentless sun had faded them to a pale lavender. Their jackets, piled in a heap near the ladder, were of a variety of cuts, colors, and origins, and had been repaired so often they were more patch than original fabric.

They lounged, with that unique, lazy insolence that only soldiers of long experience can affect, and watched the shore to the south, where something in the nature of a spectacle was unfolding. The bay was full of ships, broad-beamed, clumsy-looking transports with furled sails, wallowing visibly even in the mild sea. Out beyond them was a pair of frigates, narrow and sharklike by comparison, their muddy red Borelgai pennants snapping in the wind as though to taunt the Vordanai on the shore.

If it was a taunt, it was lost on the men on the walls, whose attention was elsewhere. The deep-drafted transports didn’t dare approach the shore too closely, so the water between them and the rocky beach was aswarm with small craft, a motley collection of ship’s boats and local fishing vessels. Every one was packed to the rails with soldiers in blue. They ran into the shallows far enough to let their passengers swing over the side into the surf, then turned about to make another relay. The men in blue splashed the last few yards to dry land and collapsed, lying about in clumps beside neatly stacked boxes of provisions and equipment.

“Those poor, stupid bastards,” said the first soldier, whose name was Buck. He was a broad-shouldered, barrel-chested man, with sandy hair and a tuft on his chin that made him look like a brigand. “Best part of a month in one of those things, eatin’ hard biscuit and pukin’ it up again, and when you finally get there they tell you you’ve got to turn around and go home.”

“You think?” said the second soldier, who was called Will. He was considerably smaller than Buck, and his unweathered skin marked him as a relative newcomer to Khandar. “I’m not looking forward to another ride myself.”

“I fucking well am,” said the third soldier, who was called—for no reason readily apparent—Peg. He was a wiry man, whose face was almost lost in a vast and wild expanse of beard and mustache. His mouth worked continually at a wad of sweetgrass, pausing occasionally to spit over the wall. “I’d spend a year on a fucking ship if it would get me shot of this fucking place.”

“Who says we’re going home?” Will said. “Maybe this new colonel’s come to stay.”

“Don’t be a fool,” Peg said. “Even colonels can count noses, and it doesn’t take much counting to see that hanging around here means ending up over a bonfire with a sharp stake up the arse.”

“Besides,” Buck said, “the prince is going to make him head right back to Vordan. He can’t wait to get to spending all that gold he stole.”

“I suppose,” said Will. He watched the men unloading and scratched the side of his nose. “What’re you going to do when you get back?”

“Sausages,” said Buck promptly. “A whole damn sack full of sausages. An’ eggs, and a beefsteak. The hell with these grayskins and their sheep. If I never see another sheep it’ll be too soon.”

“There’s always goat,” Peg said.

“You can’t eat goat,” Buck said. “It ain’t natural. If God had wanted us to eat goat he wouldn’t’ve made it taste like shit.” He looked over his shoulder. “What about you, Peg? What’re you gonna do?”

“Dunno.” Peg shrugged, spat, and scratched his beard. “Go home and fuck m’ wife, I expect.”

“You’re married?” Will said, surprised.

“He was when he left,” Buck said. “I keep tellin’ you, Peg, she ain’t gonna wait for you. It’s been seven years—you got to be reasonable. Besides, she’s probably fat and wrinkled by now.”

“Get a new wife, then,” Peg said, “an’ fuck her instead.”

Out in the bay, an officer in full dress uniform missed a tricky step into one of the small boats and went over the side and into the water. There was a chorus of harsh laughter from the trio on the wall as the man was fished out, dripping wet, and pulled aboard like a bale of cotton.

When this small excitement had died away, Buck’s eyes took on a vicious gleam. Raising his voice, he said, “Hey, Saint. What’re you gonna do when you get back to Vordan?”

The fourth soldier, at whom this comment was directed, sat against the rampart some distance from the other three. He made no reply, not that Buck had expected one.

Peg said, “Prob’ly go rushin’ to the nearest church to confess his sins to the Lord.”

“Almighty Karis, forgive me,” Buck said, miming prayer. “Someone threw a cup of whiskey at me and I might have gotten some on my tongue!”

“I dropped a hammer on my foot and said, ‘Damn!’” Peg added.

“I looked at a girl,” Buck suggested, “and she smiled at me, and it made me feel all funny.”

“Oh, and I shot a bunch of grayskins,” Peg said.

“Nah,” said Buck, “heathens don’t count. But for that other stuff you’re going to hell for sure.”

“Hear that, Saint?” said Peg. “You’re goin’ to wish you’d enjoyed yourself while you had the chance.”

The fourth soldier still did not deign to respond. Peg snorted.

“Why do you call him Saint, anyway?” said Will.

“’Cause he’s in training to be one,” Buck said. “He don’t drink, he don’t swear, and he sure as hell don’t fuck. Not even grayskins, which hardly counts, like I said.”

“What I heard,” Peg said, taking care to be loud enough that the fourth soldier would overhear, “is that he caught the black creep on his first day here, an’ after a month his cock dropped off.”

The trio were silent for a moment, considering this.

“Well, hell,” said Buck. “If that happened to me I guess I’d be drinking and swearing for all I was worth.”

“Maybe it already happened to you,” Peg shot back immediately. “How the hell would you know?”

This was familiar territory, and they lapsed into bickering with the ease of long familiarity. The fourth soldier gave a little sigh and shifted his musket into his lap.

His name was Winter, and in many ways he was different from the other three. For one thing, he was younger and more slightly built, his cheeks still unsullied by whiskers. He wore his battered blue coat, despite the heat, and a thick cotton shirt underneath it. And he sat with one hand resting on the butt of his weapon, as though at any moment he expected to have to stand to attention.

Most important, “he” was, in fact, a girl, although this would not be apparent to any but the most insistent observer.

It was certainly unknown to the other three soldiers, and for that matter to everyone else in the fort, not to mention the roll keepers and bean counters a thousand miles across the sea at the Ministry of War. The Vordanai Royal Army not being in the habit of employing women, aside from those hired for short intervals by individual soldiers on an informal basis, Winter had been forced to conceal the fact of her gender since she enlisted. That had been some time ago, and she’d gotten quite good at it, although admittedly fooling the likes of Buck and Peg was not exactly world-class chicanery.

Winter had grown up in the Royal Benevolent Home for Wayward Youth, known to its inmates as Mrs. Wilmore’s Prison for Young Ladies, or simply the Prison. Her departure from this institution had been unauthorized, to say the least, which mean that of all the soldiers in the fort, Winter was probably the only one who was of two minds about the fleet’s arrival. Everyone in camp agreed that the new colonel would have no choice but to set sail for home before the army of fanatics arrived. It was, as Buck had mentioned, certainly better than being roasted on a spit, which was the fate the Redeemers had promised to the foreigners they called “corpses” to mock their pale skin. But Winter couldn’t shake the feeling that somehow, three years later and a thousand miles away, Mrs. Wilmore would be waiting with her severe bonnet and her willow switch as soon as she stepped off the dock.

The scrape of boots on the ladder announced the arrival of a newcomer, and the four soldiers grabbed their muskets and arranged themselves to look a little more alert. They relaxed when they recognized the moon-shaped face of Corporal Tuft, flushed and sweating freely.

“Hey, Corp’ral,” said Buck, laying his weapon aside again. “You fancy a look?”

“Don’t be a moron,” Tuft said, panting. “You think I would come all the way up here just to look at a bunch of recruits learning to swim? Fuck.” He doubled over, trying to catch his breath, the back of his jacket failing to cover his considerable girth. “I swear that fuckin’ wall gets higher every time I have to climb it.”

“What are you going to do when you get back to Vordan, Corp’ral?” Buck said.

“Fuck Peg’s wife,” Tuft snapped. He turned away from the trio to face Winter. “Ihernglass, get over here.”

Winter cursed silently and levered herself to her feet. Tuft wasn’t a bad sort for a corporal, but he sounded irritated.

“Yes, Corporal?” she said. Behind Tuft, Peg made a rude gesture, which provoked silent laughter from the other two.

“Cap’n wants to see you,” Tuft said. “But Davis wants to see you first, so I’d hurry up if I was you. He’s down in the yard.”

“Right away, Corporal,” said Winter, swallowing another curse. She slung her musket over her shoulder and took hold of the ladder, her feet finding the rungs with the ease of long practice. She seemed to draw more than her share of wall duty, which was undoubtedly another little gift from the senior sergeant. Nothing was too petty for Davis.

The fortress—Fort Valor, as some Vordanai cartographer had named it, apparently not in jest—was a small medieval affair, little more than a five-sided wall with two-story stone towers at the corners. Whatever other buildings had filled it in antiquity had long since fallen to bits, leaving a large open space in which the Vordanai had raised their tents. The best spots were those right against one of the walls, which got some shade most of the day. The “yard” was the unoccupied ground in the center, an expanse of dry, packed earth that would have been ideal for drills and reviews if the Colonials had bothered with such things.

Winter found Davis waiting near the edge of the row of tents, watching idly as two soldiers, stripped to the waist, settled some minor argument with their fists. A ring of onlookers cheered the pair indiscriminately.

“Sir!” Winter went to attention, saluted, and held it until Davis deigned to turn around. “You wanted to see me, sir?”

“Ah, yes.” The sergeant’s voice was a basso rumble, apparently produced somewhere deep in his prodigious gut. Davis would have seemed fatter if he wasn’t so tall. As it was, he loomed. He was also, as Winter had had good occasion to find out, venal, petty, cruel, stupid as an ox in most respects but not without a certain vicious cunning when the situation arose. In other words, the perfect sergeant.

“Ihernglass.” He smiled, showing blackened teeth. “You heard that the captain has requested your presence?”

“Yes, sir.” Winter hesitated. “Do you know—”

“I suspect I had something to do with that. There was just one thing I wanted to make clear to you before you went.”

“Sir?” Winter wondered what Davis had gotten her into this time. The big man had made her torment a personal project ever since she’d been transferred to his company, against his wishes, more than a year before.

“The captain will tell you that your sergeant recommended you for your sterling qualities, skill and bravery and so forth. You may find yourself thinking that old Sergeant Davis isn’t such a bad fellow after all. That deep down, under all the bile and bluster, he harbored a soft spot for you. That all his taunts and jibes were well intentioned, weren’t they? To toughen you up, body and soul.” The sergeant’s smile widened. “I want you to know, right now, that that’s bullshit. The captain asked me to recommend men with good records for a special detail, and I’ve been around enough officers to know what that means. You’ll be sent off on some idiot suicide mission, and if that’s got to happen to any man in my company I wanted to be sure it was you. Hopefully, it means I will finally, finally be rid of you.”

“Sir,” Winter said woodenly.

“I find I develop a certain rough affection for most men under my command as the years wear on,” Davis mused. “Even the ugly ones. Even Peg, if you can believe it. I sometimes wonder why you have been such an exception. I knew I didn’t like the look of you the first day we met, and I still don’t. Do you have any idea why that might be?”

“Couldn’t say, sir.”

“I think it’s because, deep down, you think you’re better than the rest of us. Most men lose that conviction after a while. You, on the other hand, never seem to tire of having your face rubbed in the mud.”

“Yes, sir.” Winter had long ago found that the quickest, not to say the safest, method of getting away from an audience with Davis was simply to agree with everything the sergeant said.

“Oh, well. I had some lovely duty on the latrines lined up for you.” Davis gave a huge, rolling shrug. “But instead you get to find out what lunacy Captain d’Ivoire has dreamed up. No doubt it will be a glorious death. I just want you to remember, when some Redeemer is carving chunks out of you for his cookpot, that you’re there because old Sergeant Davis couldn’t stand the sight of you. Is that understood?”

“Understood, sir,” Winter said.

“Very well. You are dismissed.”

He turned back to the fight, which was nearly over, one man having wrapped his arm around his rival’s neck while he pounded him repeatedly in the face with his free hand. Winter trudged past them, headed for the corner tower that served as regimental headquarters.

Her gut churned. It would be good to be away from Davis. There was no doubt about that. While they’d been in their usual camp near the Khandarai capital of Ashe-Katarion, the big sergeant’s torments had been bearable. Discipline had been lax. Winter had been able to spend long periods away from the camp, and Davis and the others had had their drinking, gambling, and whoring to distract them. Then the Redemption had come. The prince had fled the capital like a whipped dog, and the Colonials had followed. Since then, through the long weeks of waiting at Fort Valor, things had gotten much worse. Cooped up inside the ancient walls, Winter had nowhere to escape, and Davis used her to vent his irritation at being denied his favorite pursuits.

On the other hand, Winter had learned to parse officer-speak, too. A “special detail” definitely sounded bad.

There was a guard at the open doorway to the building, but he only nodded at Winter as she entered. The captain’s office was just inside, marked by the smiling staff lieutenant who waited by the door. Winter recognized him. Everyone in the regiment knew Fitzhugh Warus. His brother, Ben Warus, had been colonel of the Colonials until he’d taken a bullet through the skull during a hell-for-leather chase after some bandits upriver. Fitz had been widely expected to leave for home after that, since everyone knew he was only here for his brother’s sake. Inexplicably, he’d remained, employing his easy smile and flawless memory on behalf of the new acting commander.

Winter always felt a bit uncomfortable in his presence. She had small use for officers of any description, much less officers who smiled all the time. At least when she was being shouted at, she knew where she stood.

She stopped in front of him and saluted. “Ranker Ihernglass, reporting as ordered, sir.”

“Come in,” said Fitz. “The captain is expecting you.”

Winter followed him inside. The captain’s “office” had more than likely been someone’s bedroom back when Fort Valor was an actual functioning fortress. Like every other part of the place, they’d found it stripped to the bare rock when they arrived. Captain d’Ivoire had made a kind of low desk out of half the bed of a broken cart propped on a pair of heavy trunks, and he sat on a spare bedroll.

This desk was strewn with paper of two distinct sorts. Most of it was the yellow-brown Khandarai rag paper the Colonials had used for years, recycled endlessly by enterprising vendors who rescued scraps from trash heaps and scraped the ink off, over and over, until the sheet was as thin as tissue. Amidst these, like bits of polished marble in a sand heap, were several pages of honest-to-Karis Vordanai stationery, crisp as though they had just come off the mills, bleached blindingly white with creases like razors. They were obviously orders from the fleet. Winter itched to know what they contained, but they were all carefully folded to shield them from prying eyes.

The captain himself was working on another sheet, a list of names, wearing an irritable expression. He was a broad-shouldered man in his middle thirties, face browned and prematurely wrinkled like that of anyone else who spent too much time in the unforgiving Khandarai sun. He kept his dark hair short and his beard, just starting to show slashes of gray, trimmed close to his jaw. Winter liked him as well as she liked any officer, which wasn’t much.

He looked up at her, grunted, and made a mark on his list. “Sit down, Ranker.”

Winter sat cross-legged on the floor across the desk from him. She felt Fitz hovering over her shoulder. Her instincts were screaming that this was a trap, and she had to remind herself firmly that making a break for it was not an option.

It felt as though the captain wanted her to open the conversation, but she knew better than to try. Finally he grunted again and fumbled around under the desk, coming up with a little linen bag. He tossed it on the desk in front of her, where it clanked.

“For you,” he said. When she hesitated, he gestured impatiently. “Go on.”

Winter worked her finger through the drawstring and tipped out the contents. They were two copper pins, each bearing three brass pips. They were intended for the shoulders of her uniform; the insignia of a senior sergeant.

There was a long silence.

“This has to be a joke,” Winter blurted, and then hastily added, “sir.”

“I wish it was,” the captain said, either oblivious to or intending the implied insult. “Put them on.”

Winter regarded the copper pins as though they were poisonous insects. “Sir, I must respectfully decline this offer.”

“Too bad it isn’t an offer, or even a request,” the captain snapped. “It’s an order. Put the damn things on.”

She slammed her hand on the desk, just missing the dangerously upturned point of one of the pins, and shook her head violently. “I—”

Her throat rebelled, closing so tight she had to fight for breath. The captain watched her, not angry but with a sort of bemused curiosity. After a few moments, he coughed.

“Technically,” he said, “I could have you thrown in the stockade for that. Only we haven’t got a stockade, and then I’d just have to find another damned sergeant. So let me explain.” He sorted through the papers and came up with one of the crisp sheets. “Aboard those transports are enough soldiers to bring this regiment up to book strength. That’s nearly three thousand men. As soon as they dock, I get this instruction”—he gave the word a nasty spin—“from the new colonel, telling me that he hasn’t brought any junior officers and he wants me to provide people who are ‘familiar with the natives and the terrain.’ Never mind that I haven’t got enough for my own companies. So I’ve got to come up with thirty-six sergeants, without stripping the other companies completely bare, and that means field promotions.”

Winter nodded, her chest still tight. The captain made a vague gesture in the air.

“So I ask around for men who might be able to do the job. Your Sergeant Davis picked you. Your record is”—his lip quirked—“a bit odd, but good. And here we are.”

The sergeant would be apoplectic if he knew she was being promoted, rather than sent on a dangerous foray into enemy territory. For a moment Winter reconsidered her objection. It would be worth it, almost, just to watch his face turn tomato red. To make Buck and Tuft salute her. But—

“Sir,” she protested, “with all due respect to yourself and Sergeant Davis, I don’t think this is a good decision. I don’t know how to be a sergeant.”

“It can’t be difficult,” the captain said, “or else sergeants couldn’t do it.” He sat back a little, as though waiting for a smile, but Winter kept her face rigid. He sighed. “Would it reassure you if I said that all the new companies have their own lieutenants? I doubt that your duties will involve as much . . . initiative as Sergeant Davis’ do.”

Shortage of lieutenants was a perennial problem in the Colonials. The primary purpose of the regiment, it sometimes seemed, was as a dumping ground for those who had irretrievably fucked up their Royal Army careers but hadn’t quite gone far enough to be cashiered or worse. Lieutenants—who, by and large, came from good families and were young enough to still make a life outside the service—would usually resign rather than accept the posting. Most companies were run by their sergeants, of which the regiment always had a sufficiency.

It was reassuring, slightly, but it did little to address her primary objection. She’d spent three years doing all she could to avoid contact with her fellow soldiers, most of whom were vicious brutes in any event. To now get up in front of a hundred and twenty of them and tell them what to do—the thought made her want to curl into a ball and never emerge.

“Sir,” she said, her voice a little thick, “I still think—”

Captain d’Ivoire’s patience ran out. “Your objections are noted, Sergeant,” he snapped. “Now put the damn pins on.”

With a shaking hand, Winter took the pins and fumbled with her coat. Being nonregulation, it lacked the usual shoulder straps, and after watching for a moment the captain sighed.

“All right,” he said. “Just take them and go. You have the evening to say your good-byes. We’re breaking the new men out into companies tomorrow morning, so be on the field when you hear the call.” He cast about on the table, found a bit of rag paper, and scribbled something on it. “Take this to Rhodes and tell him you need a new jacket. And try to look as respectable as possible. God knows this regiment looks shabby enough.”

“Yes, sir.” Pocketing the pins, Winter got to her feet. The captain made a shooing gesture, and Fitz appeared at her side to escort her to the door.

When they were in the corridor, he favored her with another smile.

“Congratulations, Sergeant.”

Winter nodded silently and wandered back out into the sun.

Chapter Two

Marcus

Senior Captain Marcus d’Ivoire sat at his makeshift wooden desk and contemplated damnation.

The Church said—or Elleusis Ligamenti said, but since he was a saint it amounted to the same thing—that if, after death, the tally of your sins outweighed your piety, you were condemned to a personal hell. There you suffered a punishment that matched both your worst fears and the nature of your iniquities, as devised by a deity with a particularly vicious sense of irony. In his own case, Marcus didn’t imagine the Almighty would have to think very hard. He had a strong suspicion that he would find his hell unpleasantly familiar.

Paperwork. A mountain, a torrent of paper, a stack of things to read and sign that never shrank or ended. And, lurking behind, on, and around every sheet, the looming anxiety that while this one was just the latrine-digging rota, the next one might be important. Really, critically important, the kind of thing that would make future historians shake their heads and say, “If only d’Ivoire had read that report, all those lives might have been spared.” Marcus was starting to wonder if perhaps he’d died after all and hadn’t noticed, and whether he could apply for time off in a neighboring hell. Spending a few millennia being violated by demons with red-hot pokers was beginning to sound like a nice change of pace.

What made it worse was that he didn’t have to do it. He could say, “Fitz, take care of all this, would you?” and the young lieutenant would. He’d smile while he was doing it! All that stood in the way was Marcus’ own stubborn pride and, again, the fear that somewhere in the sea of paper was something absolutely vital that he was going to miss.

Fitz returned from escorting another newly frocked sergeant out of the office. Marcus leaned back, stretching his long legs under the desk and feeling his shoulders pop. His right hand burned dully, and his thumb was developing a blister.

“Tell me that was the last one,” he said.

“That was the last one,” Fitz said obediently.

“But you’re just saying that because I told you to say it.”

“No,” the lieutenant said, “that was really the last one. Just in time, too. Signal from the fleet says the colonel’s coming ashore.”

“Thank God.”

One year ago, before Ben Warus had gone chasing one bandit too many, Marcus would have said he wanted to command the regiment. But that had been in another lifetime, when Khandar was just a sleepy dead-end post and the most the Colonials had been required to do was stand beside the prince on formal occasions to demonstrate the eternal friendship between the Vermillion Throne and the House of Orboan. Before a gang of priests and madmen—more or less synonymous, in Marcus’ opinion—had stirred up the populace with the idea that they would be better off without either one.

Since then, Khandar had become a very unpleasant place for anyone wearing a blue uniform, and Marcus had been living right at the edge of collapse, his mouth dry and his stomach awash in bile. There was something surreal about the idea that in a few minutes he was going to become a subordinate again. Hand over the command of the regiment to some total stranger, his responsibilities reduced to carrying out whatever orders he was given. It was an unbelievably attractive thought. The new man might screw things up, of course—he probably would, if Marcus’ experience with colonels was any guide—but whatever happened, up to and including the entire regiment being massacred by screaming Redeemer fanatics, it would not be his, Marcus’, fault. He’d be able to turn up for heavenly judgment and say, “Well, you can’t blame me. I had orders!”

He wondered if that carried any weight with the Almighty. It was something to tell the Ministry of War and the Concordat, at any rate, and that was probably more important. Of the two, the Almighty was a good deal less frightening. The Lord, in his infinite mercy, might forgive a soldier who strayed from the path, but the Last Duke certainly would not.

Fitz was saying something, which Marcus had missed entirely. His sleep lately was not what it ought to have been.

“What was that?” he said.

The lieutenant, well aware of his chief’s condition, repeated himself patiently. “I said that the troops are almost all ashore. No cavalry, which is a pity, but he’s brought us at least two batteries. Captain Kaanos is sending the companies up the bluff road one at a time.”

“Will there be room for everybody inside the walls?”

Fitz nodded. “I wouldn’t want to stand a siege, but we’ll be all right for a few days.”

This last was something of a joke. Fort Valor itself was a joke, actually. Like a strong lock on a flimsy door, it was effective only as long as the intruder remained polite. It had been built in the days when the most dangerous threat to a fortress was a catapult, or maybe a battering ram. Its walls were high and unsloping, built of hard native limestone that would crumble like a soft cheese once the iron cannonballs started in on it. They wouldn’t even need a siege train—you could take the place with a battery of field guns, especially since there was no way for the defenders to emplace their artillery to shoot back.

Fortunately, no siege seemed to be in the offing. The Vordanai regiment had scuttled away from Ashe-Katarion, the prince’s former capital, and as long as they looked like they were leaving, the Redeemers had been content to watch them go. Still, Marcus had bitten his fingernails to the quick during the weeks of waiting for the fleet to arrive.

“Well,” Marcus said, “I suppose we’d better go meet him.”

The lieutenant gave a delicate cough. Marcus had been with him long enough to recognize Fitz-speak for “You’re about to do something very stupid and/or embarrassing, sir.” He cast about the room, then down at himself, and got it. He was not, technically, in uniform—his shirt and trousers were close to regulation blue, but both were of Khandarai make, the cheap Vordanai standard issue having faded or torn long ago. He sighed.

“Dress blues?” he said.

“It would certainly be customary, sir.”

“Right.” Marcus got to his feet, wincing as cramped muscles protested. “I’ll go change. You keep watch—if the colonel gets here, stall him.”

“Yes, sir.”

If only, Marcus thought, watching the lieutenant glide out, I could just leave this colonel entirely to Fitz. The young man seemed to have a knack for that sort of thing.

The dress uniform included a dress sword, which Marcus hadn’t worn since his graduation from the War College. The weight on one hip made him feel lopsided, and the sheath sticking out behind him was a serious threat to anyone standing nearby when he forgot about it and turned around quickly. After five years at the bottom of a trunk, the uniform itself seemed bluer than he remembered. He’d also run a comb through his hair, for the look of the thing, and scrubbed perfunctorily at his face with a tag end of soap.

“Why, Senior Captain,” Adrecht said, coming through the tent flap. “How dapper. You should dress up more often.”

Marcus lost his grip on one of the dress uniform’s myriad brass buttons and swore. Adrecht laughed.

“If you want to make yourself useful,” Marcus growled, “you might help me.”

“Of course, sir.” Adrecht said. “Anything to be of service.”

References to Marcus’ rank or seniority from Captain Adrecht Roston were invariably mocking. He had been at the War College with Marcus, and was the “junior” by a total of seven minutes, that being the length of time that had separated the calling of the names “d’Ivoire” and “Roston” at the graduation ceremony. It had been something of a joke between them until Ben Warus had died, when that seven minutes meant that—to Adrecht’s considerable relief—command of the Colonials settled on Marcus’ shoulders instead of his.

Adrecht was a tall man, with a hawk nose and a thin, clean-shaven face. Since his graduation from the War College, he’d worn his dark curls fashionably loose. Keen, intelligent blue eyes and a slight curve of lip gave the impression that he was forever on the edge of a sarcastic smirk.

He commanded the Fourth Battalion, at the opposite end of the marching order from Marcus’ First. He and his fellow battalion commanders, Val and Mor, along with the late Ben Warus and his brother, had been Marcus’ official family ever since he’d arrived in Khandar. The only family, in fact, that he had left.

Marcus stood uncomfortably while Adrecht’s deft fingers worked the buttons and straightened his collar. Looking over the top of his friend’s head, he said, “Did you have some reason to be here? Or were you just eager to see me embarrass myself?”

“Please. Like that’s such a rarity.” Adrecht stepped back, admiring his handiwork, and gave a satisfied nod. “I take it from the getup that you’re off to meet the colonel?”

“I am,” Marcus said, trying not to show how much he wasn’t looking forward to it.

“No time for a celebratory drink?” Adrecht opened his coat enough to show the neck of a squat brown bottle. “I’ve been saving something for the occasion.”

“I doubt the colonel would appreciate it if I turned up stumbling drunk,” Marcus said. “With my luck I’d probably be sick all over him.”

“From one cup?”

“With you, it’s never just one cup.” Marcus tugged at his too-tight collar and sat down to turn his attention to his boots. There was a clatter as his scabbard knocked over an empty tin plate and banged against the camp bed, and he winced. “What have we got to celebrate, anyway?”

Adrecht blinked. “What? Just our escape from this sandy purgatory, that’s all. This time next week, we’ll be heading home.”

“So you suppose.” Marcus pulled at a stubborn boot.

“It’s not just me. I heard Val say the same thing to Give-Em-Hell. Even the rankers are saying it.”

“Val doesn’t get to decide,” Marcus said. “Nor does Give-Em-Hell, or the rankers. That would be the colonel’s prerogative.”

“Come on,” Adrecht said. “You send them a report that the grayskins have got some new priests, who aren’t too fond of us and have a nasty habit of burning people alive, and by the way they outnumber us a couple of hundred to one and the prince is getting shirty. So they send us a couple of thousand men and a new colonel, who no doubt thinks he’s in for a little light despotism, burning down some villages and teaching a gang of peasants who’s boss, that sort of thing. Then he gets here, and finds out that the aforementioned priests have rounded up an army of thirty thousand men, the militia that we trained and armed has gone over to the enemy lock, stock, and barrel, and the prince has decided he’d rather make the best of a bad job and take the money and run. What do you think he’s going to do?”

“You’re making the assumption that he has an ounce of sense,” Marcus said, pulling his laces tight. “Most of the colonels I met back at the college were not too well endowed in that department.”

“Or any another,” Adrecht said. “But not even that lot would—”

“Maybe.” Marcus got to his feet. “I’ll go and see, shall I? Do you want to come?”

Adrecht shook his head. “I’d better go and make sure my boys are ready. The bastard will probably want a review. They usually do.”

Marcus nodded, looked at himself in the mirror again, and paused. “Adrecht?”

“Hmm?”

“If we do get to go home, what are you going to do?”

“What do you mean?”

“If I recall, a certain count told you that if you ever came within a thousand miles of his daughter again, he would tie you to a cannon and drop you in the Vor.”

“Oh.” Adrecht gave a weak smile. “I’m sure he’s forgotten all about that by now.”

Marcus, feeling prickly and uncomfortable, stood beside Fitz at the edge of the bluff and watched the last few companies toiling up the road. The path switchbacked as it climbed the few hundred feet from the landing to the top of the cliff. The column of climbing men looked like a twisted blue serpent, winding its way up only to be devoured by the gaping maw of the fort’s open gate beside him. There seemed to be no end to them.

The men themselves were a surprise, too. To Marcus’ eyes they seemed unnaturally pale—he understood, suddenly, why the Khandarai slang for Vordanai was “corpses.” Compared to the leather-skinned veterans of the Colonials, these men looked like something you’d fish off the bottom of a pond.

And they were so young. Service in the Colonials was usually a reward for an ill-spent military career. Apart from the odd loony who volunteered for Khandarai service, even the rankers tended to be well into their second decade. Marcus doubted that most of the “men” marching up the road had seen eighteen, let alone twenty, given their peach-fuzz chins and awkward teenage frames. They didn’t know how to march properly, either, so the column was more like a trudging mass of refugees than an army on the move. All in all, Marcus decided, it was not a sight calculated to impress any enemies who might be watching.

He had no doubt they were watching, too. The Colonials had made no effort to patrol the hills around the fort, and while the rebel commanders might believe the Vordanai were on the verge of departing for good, they weren’t so foolish as to take it on faith. Every scrubby hill and ravine could hide a dozen Desoltai riders. The desert tribesmen could vanish on bare rock, horses and all, if they put their minds to it.

In the rear of the column, far below, a lonely figure struggled after the last of the marching companies under the burden of two heavy valises. He wore a long dark robe, which made him look a bit like a penny-opera version of a Priest of the Black. But since the Obsidian Order—perennial of cheap dramas and bogeymen of children’s stories—had been extinct for more than a century, Marcus guessed this poor bastard was just a manservant hauling his master’s kit up the mountain. One of the sinister inquisitors of old would hardly carry his own bags, anyway. He wondered idly what was so important that it couldn’t be brought up in the oxcarts with the rest of the baggage.

His eyes scanned idly over the fleet, waiting for the colonel himself to emerge with his escort. He would be a nobleman, of course. The price of a colonel’s commission was high, but there was more to it than money. While the Ministry of War might have been forced to concede over the past hundred years that there were commoners who could site guns and file papers as well as any peer, it had quietly but firmly drawn the line at having anyone of low birth in actual command. Leading a regiment was the ancient prerogative of the nobility, and so it would remain.

Even Ben Warus had been nobility of a sort, a younger son of an old family that had stashed him in the army as a sinecure. That he’d been a decent fellow for all that had been nothing short of a miracle. Going purely by the odds, this new colonel was more likely to be akin to the ones Marcus had known at the War College: ignorant, arrogant, and contemptuous of advice from those beneath him. He only hoped the man wasn’t too abrasive, or else someone was likely to take a swing at him and be court-martialed for his trouble. The Colonials had grown slack and informal under Ben’s indulgent command.

The servant with the bags had reached the last switchback, but there was still no flurry of activity from the ships that would indicate the emergence of an officer of rank. More boats were landing, but they carried only supplies and baggage, and the laboring men down at the dock were beginning to load the carts with crates of hardtack, boxes of cartridges, and empty water barrels. Marcus glanced at Fitz.

“The colonel did say he was coming up, didn’t he?”

“That was the message from the fleet,” the lieutenant said. “Perhaps he’s been delayed?”

“I’m not going to stand out here all day waiting,” Marcus growled. Even in the shade, he was sweating freely.

He waited for the porter in black to approach, only to see him stop twenty yards away, set down both valises, and squat on his heels at the edge of the dusty path. Before Marcus could wonder at this, the man leaned forward and gave an excited cry.

Balls of the Beast, he’s stepped on something horrible. Khandar was home to a wide variety of things that crawled, slithered, or buzzed. Nearly all of them were vicious, and most were poisonous. It would be a poor start to a professional relationship if Marcus had to report to the colonel that his manservant had died of a snakebite. He hurried down the path, Fitz trailing behind him. The man in black popped back to his feet like a jack-in-the-box, one arm extended, holding something yellow and green that writhed furiously. Marcus pulled up short.

“A genuine Branded Whiptail,” the man said, apparently to himself. He was young, probably younger than Marcus, with a thin face and high cheekbones. “You know, I’d seen Cognest’s illustrations, but I never really believed what he said about the colors. The specimens he sent back were so drab, but this—well, look at it!”

He stepped forward and thrust the thing in Marcus’ face. Only years of army discipline prevented Marcus from leaping backward. The little scorpion was smaller than his palm, but brilliantly colored, irregular stripes of bright green crisscrossing its dun yellow carapace. The man held it by the tail with thumb and forefinger, just below the stinger, and despite the animal’s frantic efforts it was unable to pull itself up far enough to get its claws into his flesh. It twisted and snapped at the air in impotent rage.

It dawned on Marcus that some response was expected of him.

“It’s very nice,” he said cautiously. “But I would put it down, if I were you. It might be dangerous.” Truth be told, Marcus couldn’t have distinguished a Branded Whiptail from horse droppings unless it bit him on the ankle, but that didn’t mean he wouldn’t give both a wide berth.

“Oh, it’s absolutely deadly,” the man said, wiggling his fingers so the little thing shook. “A grain or two of venom will put a man into nervous shock in less than a minute.” He watched Marcus’ carefully neutral expression and added, “Of course, this must all be old hat to you by now. I’m sorry to get so worked up right off the bat. What must you think of me?”

“It’s nothing,” Marcus said. “Listen, I’m Captain d’Ivoire, and I got a message—”

“Of course you are!” the man said. “Senior Captain Marcus d’Ivoire, of the First Battalion. I’m honored.” He extended his hand for Marcus to shake. “I’m Janus. Most pleased to meet you.”

There was a long pause. The extended hand still held the frantically struggling scorpion, which left Marcus at something of a loss. Finally Janus followed his gaze down, laughed, and spun on his heel. He walked to the edge of the path and dropped the little thing amidst the stones. Then, wiping his hand on his black robe, he returned to Marcus.

“Sorry about that,” he said. “Let me try again.” He re-offered his hand. “Janus.”

“Marcus,” Marcus said, shaking.

“If you could conduct me to the fortress, I would be most grateful,” Janus said. “I just have a few things I need to get stowed away.”

“Actually,” Marcus said, “I was hoping you could tell me where the colonel might be. He sent a message.” Marcus looked over his shoulder at Fitz for support.

Janus appeared perplexed. Then, looking down at himself, inspiration appeared to dawn. He gave a polite cough.

“I suppose I should have been clearer,” he said. “Count Colonel Janus bet Vhalnich Mieran, at your service.”

The Thousand Names © Django Wexler 2013