When you read fiction that is particularly weird and disturbing, you can’t help but wonder how much of the author’s neuroses are bleeding through into the stories. If that does happen, Jeff VanderMeer must have some really strange nightmares. He’d be so much safer in a nice, clean, stainless steel cell, where nothing from the natural world can get at him.

Squid, Mushroom People, Meerkats: Jeff knows that there are Things out there. He knows that they are self-aware, and suspects that they are watching us. This is no Lovecraftian horror of the vast cosmic unknown. It isn’t even H.G. Wells with his Martian minds unmeasurable to man. This is a very nearby terror, one that could all too easily be real.

Like many writers, Jeff beavered away in obscurity for many years before hitting the big time. His early work appeared in small press editions published by his future wife, Ann. These days Jeff and Ann are both at the top of their professions—he as a writer, and she as fiction editor for Tor.com. Both, however, have paid their dues, working their way to the top the hard way.

Jeff first came to the attention of a wider audience in 2000 when a novella called “The Transformation of Martin Lake” won a World Fantasy Award. It had appeared in a small press horror anthology called Palace Corbie (#8 in the series, if you are looking for it). The story tells of a struggling young artist who receives an invitation “to a beheading,” unaware that he will have a key part to play in this event. It is a tale of personal disintegration, a theme that will become common in VanderMeer’s fiction, but it is most notable for being set in the city of Ambergris. Martin Lake’s woes begin when he is discovered by a well-known art critic, Janice Shriek.

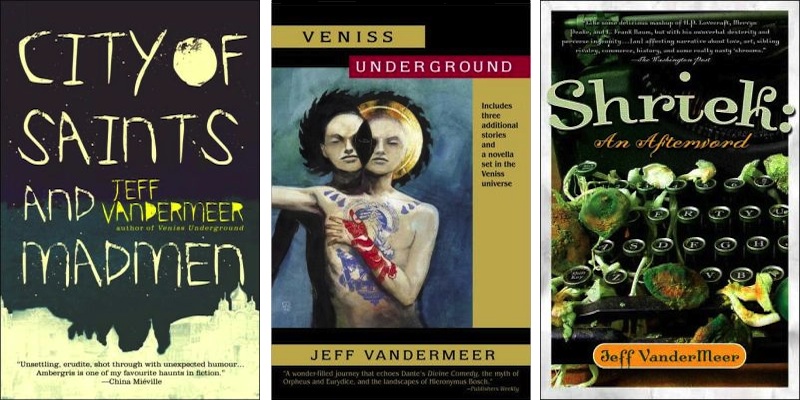

The following year saw the publication of the first edition of City of Saints and Madmen, which can be seen either as a mosaic novel, or a collection of short fiction, or perhaps as an indispensable tour guide to one of the strangest cities in fantasy. “The Transformation of Martin Lake” is a key part of the book; as is the novella, “Dradin in Love”—another tale of an innocent young man whose life takes a turn for the worse.

The story of how City of Saints and Madmen came to be could easily be yet another saga of personal disintegration. Jeff told the whole sorry tale to a webzine appropriately called The Agony Column. It is still online if you want to read it. The action takes place in the early days of print-on-demand publishing when a whole raft of independent small presses were just learning to use the new technology, some more effectively than others. Jeff’s ambitious project was just the sort of thing that would break the unwary wannabe publisher.

Fortunately the story has a happy ending. Sean Wallace, who published the early editions, has gone on to create a successful company in Prime Books, as well as to win multiple awards as part of the editorial staff of Clakesworld Magazine. And the book that caused all that trouble finally found its way to a big publisher thanks to Julie Crisp’s predecessor at Tor UK, the legendary Peter Lavery.

What exactly is so great about City of Saints and Madmen? Well there is the ambition and experimentation, to be sure. More of that later. The thing that caught the eyes of genre fans, however, was the wonderfully imaginative—some might say obsessive—worldbuilding. It is the sort of thing that invites comparison to the work that Tolkien did to create Middle-earth. There is nowhere near as much of it, but VanderMeer manages to conjure a particular vision of Ambergris through the connections he builds in his stories.

Dradin—he of the doomed love affair—works for Hogebottom & Sons, the premier publishing company of the city. That company also published a number of other works re-printed as part of, or referenced in, City of Saints and Madmen. One of their most famous books is The Hogebottom Guide to the Early History of the City of Ambergris. It was written by Duncan Shriek, the historian brother of the art critic who discovered Martin Lake. It is also a key source of information about the creatures who live in the tunnels under the city: the mushroom people known as Gray Caps.

Elsewhere in the book we learn of the Festival of the Freshwater Squid, a city-wide celebration that can quickly turn murderous. We meet Frederick Madnok, who may or may not be a learned expert of the subject of these squid. The story “King Squid” is written in the style of an academic monograph about these majestic creatures, complete with an annotated bibliography.

Remember that I said that VanderMeer was ambitious and experimental? Well some of the parts of City of Saints and Madmen are not just printed as text, they are made to look like reproductions of the original publications by Hogebottom & Sons. And then there is “The Man Who Had No Eyes,” a story that was written entirely in code. In order to read it, you had to decipher it. And, inevitably, some people did.

Tor UK’s 2004 edition of City of Saints and Madmen is widely regarded as the definitive edition of the book. It has two additional stories that were not in earlier editions. It has the beautiful Scott Eagle artwork. It has all of the mad typography and the enciphered story just as Jeff imagined them. Sadly later, mass market editions have simplified the production, and “The Man Who Had No Eyes” is no longer enciphered. Do track down the 2004 hardcover if you can. It is well worth the £30 being asked for it.

Before returning to the city of Ambergris—for there is much more to be learned about it—we must take a quick journey into the future to visit another marvellous urban location, Veniss. This is the setting for Veniss Underground, an unashamedly science fiction novel that Jeff produced in 2003. It features meerkats genetically engineered to have opposable thumbs and intelligence so that they can act as servants. There are also artificial creatures known as ganeshas, based squarely on the Hindu god of the same name.

VanderMeer’s love of experimentation shines through this novel too. It is written in three parts, each from the point of view of a different major character. One section is written in the first person, one in the second person, and one in the third. It takes a considerable amount of writerly skill to do that sort of thing and make it work.

Despite the science fiction setting, the book soon draws in fantasy themes as the characters get involved in goings on in tunnels beneath the city. (Do you spot a theme developing here? You should do.) There are echoes of the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, and of Dante’s Inferno. It is the meerkats, however, who steal the show (and that’s 6 years before Aleksandr Orlov first appeared in an advert).

Meanwhile, back in Ambergris, things are not well. Duncan Shriek’s investigations of the Gray Caps have ended in his disappearance into the tunnels beneath the city. Grief-stricken, Janice writes a biography of her brother, detailing his disastrous love affair with his former student, Mary Sabon, and bringing to light some of the dreadful secrets of the city’s past.

More than two hundred years before, twenty-five thousand people had disappeared from the city, almost the entire population, while many thousands had been away, sailing down the River Moth to join in the annual hunt for fish and freshwater squid. The fishermen, including the city’s ruler, had returned to find Ambergris deserted. To this day, no one knows what happened to those twenty-five thousand souls, but for any inhabitant of Ambergris, the rumor soon seeps through—in the mottling of fungi on a window, in the dripping of green water, in the little red flags they use as their calling cards—that the gray caps were responsible. Because, after all, we had slaughtered so many of them and driven the rest underground. Surely this was their revenge?

Before the manuscript can be published, however, Janice too disappears. When her work is found it is covered in annotations, purportedly by Duncan, some of which flatly contradict what Janice has written. The book is finally published by Hogebottom & Sons, er, sorry, by Tor as Shriek: An Afterword.

The Gray Caps are one of my favourite fantasy races (or should that be alien races?). While they are cast in the role of an oppressed native tribe displaced from their home by foreign colonists, they also have the most awesome fungal technology: spore guns, fungal bombs, memory bulbs and so on.

The final piece of the puzzle, the book that explains who the Gray Caps really are, is Finch. Sadly it is available from a different publishing house. Rumours that they attacked Tor Towers with fungal bombs in order to secure the rights are hotly denied by all involved. Peter Lavery may, or may not have disappeared into mysterious tunnels beneath London. Suggestions that Tor staff feast on mushrooms every evening are also dismissed as hearsay, propaganda, and the ravings of a deranged inmate of the Voss Bender Memorial Mental Hospital of Ambergris (a place almost as busy as Arhkam Asylum).

Welcome to Ambergris. Enter at your own risk.

This post also appears on Tor UK’s blog.

Cheryl Morgan is a writer, editor and publisher who has been around so long that she remembers the days before the Internet. Find her on Twitter @CherylMorgan.