What comes to mind when you hear Cinderella?

How about Beauty and the Beast?

Snow White?

I bet each of those titles conjures up a particular vision related to a well-known cartoon mouse. Don’t feel bad if that’s the case; it is for me as well. Let’s take a look at why that is, for many of us.

Fairy tales are unique creatures in the literary world, thanks to this idea of the classics as told by the Brothers Grimm then later adapted by Disney. For instance, when someone mentions Cinderella, the first thought that pops into mind—at least for me—is Disney’s version. That’s the one I grew up with, my sisters and I wore that VHS (Google it) out. Then I think about the version from the Grimm stories where the stepsisters disfigure their feet to fit into the glass slipper. But what about the iterations that inspired those tales? What about the ninth-century Chinese story of Ye Xian, who uses a wish from magic bones to create a beautiful gown to go after her beloved? I love fairy tales, but the idea they have to follow these “rules” set down by the unoriginal European versions has always bothered me.

When I started writing A Blade So Black there was a part of me that recognized this as an opportunity to push back against the conceptual rules surrounding “classic” fairy tales. After all, I had grown up listening to and watching these stories about princesses going on adventures, falling in love, having their lives turned upside down then made all the better by magic, and not once did I think that could be me. Sure, I loved the stories and watched the films repeatedly, but I never wanted to be Belle or Ariel for Halloween. I never wanted an Aurora or Snow White costume. Neither did any of my sisters. We were young but we understood the rules, even though no one stated them explicitly: this is not for you, Black Girl. You have no place here, Black Girl. You are to observe but not participate, Black Girl.

Now that I think about it, none of my cousins or the Black kids at school dressed in these costumes either. What we wore was always connected to the tales by proxy, maybe a generic princess or a sparkling fairy. That was close enough to count, right? Then Princess Jasmine came along, and we finally had a brown princess we could be more connected to. Then the comments started about how we didn’t match her either, or any of the other non-white princesses. We weren’t allowed to be part of the princess craze that hit during the ’90s. We had to watch from the sidelines or risk ridicule. It was hurtful to be shut out of the stories that were essentially shoved down our throats our whole lives. Then came Tiana.

Tiana was announced, and every Black woman and girl I know lost our collective ish. Finally, we thought as we celebrated, finally we have a princesses. We can be part of this. We won’t be cast aside anymore. That joy was short-lived. Yes, we finally had a Black princess, but then you watch the movie and she spends over 80% of it as a fricken frog. It was bittersweet, heavy on the bitter, and I’m still salty about it to this day. It’s a special sort of cruelty to make something the central focus of a generation of media, to essentially bludgeon the world with it, but to only allow a fraction of the populace to take part. Then, when you allow someone else in, they don’t even get to see themselves but instead this animal in their place. That’s kinda how publishing does stories in general, animals have more rep than non-white readers, but that’s a conversation for another time.

Then the retellings-and-reimaginings trend started to kick in, first on the page, then on screen. Ninety-nine percent of those new iterations reimagined many elements of the stories but always overlooked one in particular: the characters’ race. The narrative remained centered around whiteness and white characters. There was one exception that I can remember and that’s the Cinderella movie staring Brandy and Whitney Houston. It’s the main Cinderella movie we watch in my family, and we’re very happy to have it, but it’s one film out of dozens. Possibly hundreds. And now, for the first time in over 20 years, there’s mere talk of a Black actress playing one of these princesses (Zendaya as Ariel) and people are against it. They say things like, “Dark skin wouldn’t naturally occur under water, away from sunlight,” or, “This is a European tale, tell your own,” which is honestly racist and anti-black as all hell. There’s no reason this one version of Ariel can’t be Black. It won’t erase the tens of others out there. Still, people are pushing back against it, and the “tell your own” thing really chaps my ass. Here’s why.

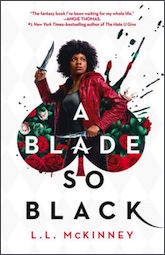

Buy the Book

A Blade So Black

Many members of the diaspora—I’m speaking to my experience of being Black American—who live in the US don’t know “our own” stories, so we can’t tell them. Thanks, slavery. We’re searching for them, digging up the past and the truths therein, but that doesn’t change the fact that we were given these Disneyfied versions of fairy tales as well. We were in the theaters, our parents purchased the toys, we collected the movies for home viewing. Our families’ money spent just as well, even though we were aware of the unspoken rule that it wasn’t for us. Black kids grew up on these stories just like white kids, so why can’t these fairy tales be shifted to reflect us as well? I’ll give you a hint; it starts with R and ends with acism.

After being denied space to enjoy fairy tales for so long, then having the rug pulled from under me with what amounts to a mean joke—I love my Tiana for what she’s supposed to be, don’t go thinking I’m throwing shade at her, I’ll fight someone over my princess—I wasn’t having it anymore. So I wrote my Alice, and when she was announced to the world, I received some hate. I was accused of “blackwashing,” which isn’t a real thing, and was told I should “tell my own” stories instead of taking them from … I don’t rightly know. The haters weren’t clear on that one.

I’ve said this before, but it bears repeating: These are my stories. Alice in Wonderland belongs to me to reimagine as much as it belongs to any of the white authors who’ve told the story in their own way without being harassed. I’m telling it my way, with a Black Alice. That changes the story fundamentally. Some of the recognizable elements from the original will be altered or missing. This will bother some people, and that’s all right. That being said, I’m not taking anything from anyone. For one thing, I can’t take what’s already mine, and fairy tales and classic children’s stories have belonged to non-white readers from the beginning. That’s the truth of it—a truth the world is going to have to accept. I know this pisses people off, and I’m here to bask in all the angry tears. I bottle and bathe in them. Keeps my skin moisturized. Plus I need to stay hydrated while I write the second book.

Black Alice is here to stay, y’all, and I can’t wait to see who’s next.

L.L. McKinney is a writer, a poet, and an active member of the kidlit community. She’s an advocate for equality and inclusion in publishing, and the creator of the hashtag #WhatWoCWritersHear. She’s spent time in the slush by serving as a reader for agents and participating as a judge in various online writing contests. She’s also a gamer girl and an adamant Hei Hei stan. A Blade So Black is her debut novel.