Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

Today we’re looking at Algernon Blackwood’s “The Wendigo,” first published in 1910 in The Lost Valley and Other Stories. Spoilers ahead.

“No one troubled to stir the slowly dying fire. Overhead the stars were brillian in a sky quite wintry, and there was so little wind that ice was already forming stealthily along the shores of the still lake behind them. The silence of the vast listening forest stole forward and enveloped them.”

Summary

Dr. Cathcart and his nephew, divinity student Simpson, travel to Northwestern Ontario to hunt moose. They’re joined by guides Hank Davis and Joseph Défago, and camp cook Punk. Just to keep our cast straight, Cathcart and Simpson are Scottish, the former interested in “the vagaries of the human mind” as well as moose, the latter a good-natured tenderfoot. Davis is Walter Huston a couple decades before Treasure of the Sierra Madre, master of creative cussing and the outback. Défago is a “French Canuck” steeped in woodcraft and the lore of voyageur ancestors. As a “Latin type,” he’s subject to melancholy fits, but his passion for the wilderness always cures him after a few days away from civilization. Punk’s an “Indian” of indeterminate nation—naturally he’s taciturn and superstitious, with animal-keen senses.

Alas, the moose are uncommonly shy this October, and our party goes a week without finding a single trace of the beasts. Davis suggests they split up, he and Cathcart heading west, Simpson and Défago east to Fifty Island Water. Défago’s not thrilled with the idea. Is something wrong with Fifty Island Water, Cathcart asks. Nah, Davis says. Défago’s just “skeered” about some old “feery tale.” Défago declares he’s not afraid of anything in the Bush; before the evening’s out, Davis talks him into the eastward trip.

While the others sleep, Punk creeps to the lakeside to sniff the air. The wind’s shifted. Down “the desert paths of night” it carries a faint odor, utterly unfamiliar.

Simpson and Défago’s trip is arduous but uneventful. They camp on the shore of the Water, on which pine-cloaked islands float like a fairy fleet. Simpson’s deeply impressed by the sheer scale and isolation of the Canadian wilderness, but his exaltation is tempered by disquiet. Haven’t some men been so seduced by it they wandered off to starve and freeze? And might Défago be one of that susceptible sort?

By the campfire that night, Défago grows alarmed by an odor Simpson doesn’t detect. He mentions the Wendigo, a legendary monster of the North, fast as lightning, bigger than any other creature in the Bush. Late at night Simpson wakes to hear Défago sobbing in his sleep. He notices the guide has shifted so his feet protrude from the tent. Weariness wins over nerves—Simpson sleeps again until a violent shaking of the tent rouses him. A strange voice, immense yet somehow sweet, sounds close overhead, crying Défago’s name!

And the guide answers by rushing from the tent. At once his voice seems to come from a distance, anguished yet exulting. “My feet of fire! My burning feet of fire!” he cries. “This height and fiery speed!”

Then silence and an odor Simpson will later describe as a composite of lion, decaying leaves, earth, and all the scents of the forest. He hunts for Défago and discovers tracks in the new-fallen snow, big and round, redolent with the lion-forest odor. Human prints run alongside them, but how could Défago match the monstrously great strides of his—quarry? Companion? More puzzling, the human tracks gradually morph to miniature duplicates of the beast’s.

The tracks end as if their makers have taken flight. High above and far away, Simpson again hears Défago’s complaint about his burning feet of fire.

Next day Simpson returns alone to the base camp. Cathcart assures him the “monster” must have been a bull moose Défago chased. The rest was hallucination inspired by the “terrible solitudes” of the forest. Cathcart and Davis accompany Simpson back to Fifty Island Water. They find no sign of Défago and fear he’s run mad to his death. Night. Campfire. Cathcart tells the legend of the Wendigo, which he considers an allegory of the Call of the Wild. It summons its victims by name and carries them off at such speed their feet burn, to be replaced by feet like its own. It doesn’t eat its victims, though. It eats only moss!

Overcome with grief, Davis yells for his old partner. Something huge flies overhead. Défago’s voice drifts down. Simpson calls to him. Next comes a crashing of branches and a thud on the frozen ground. Soon Défago staggers into camp: a wasted caricature, face more animal than human, smelling of lion and forest.

Davis declares this isn’t his friend of twenty years. Cathcart demands an explanation of Défago’s ordeal. Défago whispers he’s seen the Wendigo, and been with it too. Before he can say more, Davis howls for the others to look at Défago’s changed feet. Simpson sees only dark masses before Cathcart throws a blanket over them. Moments later, a roaring wind sweeps the camp, and Défago blunders back into the woods. From a great height his voice trails off: “My burning feet of fire….”

Through the night Cathcart nurses the hysterical Davis and Simpson, himself battling an appalling terror of the soul. The three return to base camp to find the “real” Défago alone, scrabbling ineffectually to make up the fire. His feet are frozen; his mind and memory and soul are gone. His body will linger only a few weeks more.

Punk’s long gone. He saw Défago limping toward camp, preceded by a singular odor. Driven by instinctive terror, Punk started for home, for he knew Défago had seen the Wendigo!

What’s Cyclopean: We never do get to hear Hank’s imaginative oaths directly with their full force.

The Degenerate Dutch: The characters all draw on simple stereotype, from the stalwart Scotsmen to the instinct-driven “Canuck” and “Indian.” Particularly delightful is Punk, who in spite of being part of a “dying race” scarcely looks like a “real redskin” in his “city garments.” There’s also one random but unpleasant use of the n-word (and not in reference to a cat, either).

Mythos Making: “Yet, ever at the back of his thoughts, lay that other aspect of the wilderness: the indifference to human life, the merciless spirit of desolation which took no note of man.” Sound familiar? Like Lovecraft’s cosmos, Blackwood’s forest contains forces beyond human comprehension—and through scale and age forces us to acknowledge our own insignificance. And like Lovecraft’s cosmos it tempts insignificant man, even unto his own destruction.

Libronomicon: The events reported in “The Wendigo” do not appear in Dr. Cathcart’s book on Collective Hallucination.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Dr. Cathcart uses psychological analysis to paper over his nephew’s initial reports of Défago’s disappearance with rationality. But there’s real madness in the woods, and eventually it’s all Défago’s left with.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Brilliant, but. “The Wendigo” is passages of staggering and startling beauty, drawing you ahead through eerie and terrifying lacunae—and then you plant your foot squarely in a racist turd. You wipe off your feet, continue forward, and again find yourself all admiration of the story’s brilliance…

I loved this story and found it deeply frustrating. The frustration isn’t story-killing—Blackwood’s prejudice isn’t Lovecraft’s bone-deep hatred and fear, merely a willingness to rely on convenient stereotype in place of real characterization. And unlike Lovecraft’s core terror of non-Anglos, the racism could have been excised and left a better story. I can see what Blackwood was doing with it—it’s deliberate as every other aspect of his craft—but he could have done something else. This week, this year, being what it is, I’m not willing to just gloss that over with a “but it’s brilliant.”

But, still. I should back up a moment and talk about that brilliance, because in spite of my frustration this is really, really good. Of Lovecraft’s “modern masters” that we’ve covered so far, Blackwood’s mastery is most apparent. If I hadn’t kept stepping in gunk, in fact, I might have been too caught up in the brilliance to dissect it—as is, I want to pull apart all the gears and figure out what makes it work so well, and if you could maybe fit them back together with fewer racist cow patties screwed into the works.

This may be the best use of implication that I’ve ever seen in a horror story. Blackwood leaves nothing to the imagination, except for precisely those things that gain the greatest effect from being left to the imagination. His descriptions of the Canadian woods are spare, but vivid and richly sensuous, familiar in their calm awe. I’m not normally tempted to compare our Reread stories to Thoreau, but Blackwood’s intimacy with nature shows.

When something unnatural intrudes, the contrast becomes sharper against the vivid reality of those woods. Blackwood sharpens the contrast further still by what he doesn’t show–the thing that pulls Défago from the tent, the shape of the footprints—or by what he shows inexactly. The Wendigo’s voice is “soft” but has enormous volume, hoarse but sweetly plaintive? Hard to imagine, but I keep trying. He didn’t do that by accident.

The obnoxious stereotypes of Scotsman and Indian, I think, are intended as a middle cog between the realistic landscape and the indescribable wendigo. Brushstroke characterization that would give the 1910 reader a swift image of the characters, no need to sketch out full and detailed personalities. Plus he can then invoke that cute hierarchy of civilizations, with “primitives” gaining story-convenient abilities instinctive to those of “Indian blood” (who of course never train important survival skills from childhood) and “civilized” folk overanalyzing the whole thing. And he can emphasize how both are in different ways vulnerable to the burning call of the wild. But for me, this middle cog grinds unpleasantly, and the over-simplicity and two-dimensionality bring me to a screeching halt in the middle of otherwise-perfect transitions.

I suspect I’d be even more annoyed if I knew more about the original Wendigo legend, but I’ll have to leave that to better-informed commenters.

One of the story’s inaccurate assumptions isn’t Blackwood’s fault, but the truth adds an interesting twist. You know those brush-cleared woods, the ones that would “almost” suggest intervention by “the hand of man” if it weren’t for the signs of recent fire? According to modern research, guess how those fires frequently got started? Turns out Scottish hunters aren’t the only people who appreciate clear pathways through the woods. First Nations folk did a lot of landscaping.

Not quite sure what that implies about Blackwood’s wild and pre-human wendigo, except that perhaps humans are more responsible for its existence than they like to admit.

Anne’s Commentary

I hope I don’t shock anyone with this observation, but gardens and parks and farms are as indifferent to humanity as any boreal forest. They strike us as friendly and nurturing because we’ve planned them, made them, exploit them. They are, in fact, the basis of our civilization. Vast cornfields, admittedly, are creepy—see King’s “Children of the Corn” and Preston and Child’s Still Life with Crows. Weeds are bad, too, because they’re the first sign things are getting out of control in our rationally groomed environments. A haunted house or cemetery without rank vegetation is a rarity in Lovecraft’s work. Champion of weed horror may be Joseph Payne Brennan’s “Canavan’s Backyard,” in which the supposedly circumscribed overgrowth turns out to be as limitless as Blackwood’s Bush.

Okay, though. Trees are scarier than weeds—again, see all those twisted and grasping ones Lovecraft imagines to suck unnamable nourishment from the soil. Whole boreal forests of them are especially terrible, because as Défago tells Simpson, “There’s places in there nobody won’t never see into—nobody knows what lives there either.” Simpson queries, “Too big—too far off?” Just so. The cosmos in earthly miniature, you might say.

Lovecraft places Blackwood among his modern masters for he is king of “weird atmosphere,” emperor of recording “the overtones of strangeness in ordinary things and experiences.” Blackwood builds “detail by detail the complete sensations and perceptions leading from reality into supernormal life and vision.” This command of setting and psychology lifts “Wendigo” as high in my personal pantheon as the Wendigo itself spirits its victims into the sky. Blackwood’s love of the wilderness, his outdoorsman experience, resonate like voyageur song in every description—like the singer of voyageur songs, Défago, they push so deep and so acutely into the natural that they penetrate into the supernatural. Awe couples with terror. Man, those two are always going at it, aren’t they?

I don’t have space even to begin to explore Native American wendigo lore, which varies from people to people. Cannibalism, murder and greed are normally its dominant characteristics, and however much this malevolent spirit devours, it’s never sated. Therefore it’s associated with famine, starvation and emaciation as well as cold and winter. Blackwood makes use of both Wendigo as elemental force and as the possessor/transformer of its victim. Interesting that he doesn’t go into that cannibalism thing—his Wendigo is, of all things, a moss-eater; nor does Défago possessed try to munch down on his rescuers. Huh. Is moss-eating part of a Wendigo tradition I haven’t come across yet?

Cannibalism could be considered the most extreme form of antisocial greed, and so it was taboo among the native peoples, who embodied it in the wendigo. Greedy individuals might turn into wendigos. The culture-bound disorder called Wendigo psychosis, in which the sufferer develops an intense craving for human flesh, seems linked to the taboo. But Blackwood’s not interested, again, in cannibalism. The only greed Défago’s guilty of is a hunger for the great wilderness. His infatuation waxes so keen that it draws the Wendigo to him, or he to it.

The latter Cathcart would contend, for he deems the Wendigo the “Call of the Wild” personified. Simpson’s eventual conclusions are less scientific but perhaps more accurate. He believes the Wendigo is “a glimpse into prehistoric ages, when superstitions…still oppressed the hearts of men; when the forces of nature were still untamed, the Powers that may have haunted a primeval universe not yet withdrawn—[they are] savage and formidable Potencies.”

I think Lovecraft must have gotten a sympathetic charge out of Simpson’s “Potencies.” Are they not precursors or at least cousins of the Mythos deities? Do They not walk among us, as the veils between dimension are woefully thin in places? Do They not have a distinctive odor, and is it not by this (nasty) smell we may know Them? I want to host a fantasy dinner with Abdul Alhazred and an Algonquian shaman or two—they’d have much in common to discuss, no doubt.

Anyhow, in 1941 August Derleth made the connection between Blackwood’s Wendigo and his own creation, the Walker of the Wind Ithaqua. Brian Lumley would further develop Ithaqua in his Titus Crow series. I’m afraid Ithaqua is not given to a vegan (bryophagic!) lifestyle. And that’s as it should be. The great Mythos entities do not eat moss. Except maybe for the shoggoths, if there’s nothing juicier around.

We’re going to lose power any second now, so bowing to the power of nature I will not try and think of anything clever to say about Thomas Ligotti’s “The Last Feast of Harlequin,” other than that we’ll read it next week and you can find it in, among other places, the Cthulhu 2000 anthology.

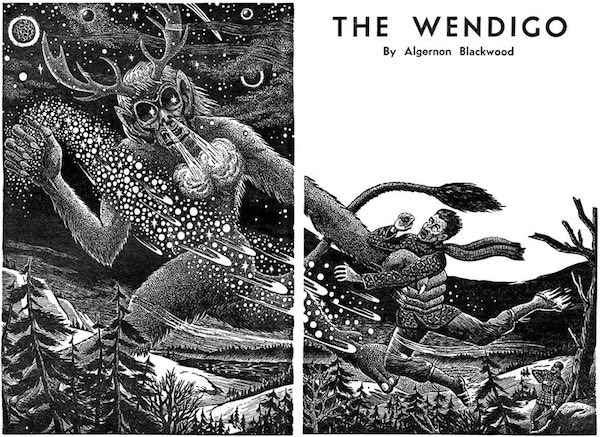

Image: Matt Fox’s illustration from Famous Fantastic Mysteries, June 1944.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Odd. I came into this thinking this is the one where a guy goes fishing at a remote Canadian lake, tries the opposite shore where no one ever goes because the fishing is better there, and has a weird experience. Then I thought it was the one where one of the hunters treats the Native American guide horribly, tracks a wounded moose (or was it a bear?) into a weird lost valley/Peaceable Kingdom where he transforms into a beast, and then the guide comes back and rescues everybody with his mystic native powers. And yet it’s neither of those, even though I read it not all that long ago. Now I’m not even sure those other stories are Blackwood.

In any case, Blackwood was a tremendous writer, despite the occasional prevalence of racist cow pats, and seems to have had a rather ambivalent attitude about nature. A lot of his stories take place out in the wilderness where weird and terrible things happen, yet he seems to have had a love of it as well. Even some of the John Silence stories are rather outdoorsy.

I still rate this story second to “The Willows”, despite the latter being a touch over long.

One of Blackwood’s finest tales; as in “The Willows”, the wilderness borders on higher spaces.

Lovecraft on Blackwood: from, once more, “Supernatural Horror in Literature”:

“Less intense than Mr. Machen in delineating the extremes of stark fear, yet infinitely more closely wedded to the idea of an unreal world constantly pressing upon ours, is the inspired and prolific Algernon Blackwood, amidst whose voluminous and uneven work may be found some of the finest spectral literature of this or any age. Of the quality of Mr. Blackwood’s genius there can be no dispute; for no one has even approached the skill, seriousness, and minute fidelity with which he records the overtones of strangeness in ordinary things and experiences, or the preternatural insight with which he builds up detail by detail the complete sensations and perceptions leading from reality into supernormal life or vision. Without notable command of the poetic witchery of mere words, he is the one absolute and unquestioned master of weird atmosphere; and can evoke what amounts almost to a story from a simple fragment of humourless psychological description. Above all others he understands how fully some sensitive minds dwell forever on the borderland of dream, and how relatively slight is the distinction betwixt those images formed from actual objects and those excited by the play of the imagination.

Mr. Blackwood’s lesser work is marred by several defects such as ethical didacticism, occasional insipid whimsicality, the flatness of benignant supernaturalism, and a too free use of the trade jargon of modern “occultism”. A fault of his more serious efforts is that diffuseness and long-windedness which results from an excessively elaborate attempt, under the handicap of a somewhat bald and journalistic style devoid of intrinsic magic, colour, and vitality, to visualise precise sensations and nuances of uncanny suggestion. But in spite of all this, the major products of Mr. Blackwood attain a genuinely classic level, and evoke as does nothing else in literature an awed and convinced sense of the immanence of strange spiritual spheres or entities.

…Another amazingly potent though less artistically finished tale is “The Wendigo”, where we are confronted by horrible evidences of a vast forest daemon about which North Woods lumbermen whisper at evening. The manner in which certain footprints tell certain unbelievable things is really a marked triumph in craftsmanship.”

Blackwood on Lovecraft: three of Lovecraft’s four modern masters were aware of his work: is there any evidence that Blackwood can be added to that number?

Teddy and the Wendigo: from The Wilderness Hunter.

A few years before Blackwood’s story: Jack Fiddler killed his last wendigo.

For Champion of Weed Horror, I’d propose Karl Edward Wagner’s “Where the Summer Ends”.

Margaret Atwood had some discussion of the Wendigo theme in her book “Strange Things”, as I recall. Ogden Nash took it on too, not just in an eponymous poem but the to me much better “The Buses Headed For Scranton”. Of course almost anyone could be better than Lumley; don’t get me started.

So um… off topic, but, how about that Lovecraft anthology series Legendary is doing?

http://www.bleedingcool.com/2016/07/20/scoop-lovecraft-series-in-the-works-at-legendary-tv/

Are you excited? Because I’m pretty damn excited.

I’ve been hoping this one would turn up here ever since I read it last year, in the Blackwood collection “Ancient Sorceries and Other Weird Stories”. Blackwood is perhaps the writer I’ve yet encountered who best put the ‘cosmic’ in ‘cosmic horror’, in the sense that the story is driven by a world that is uncaring rather than malicious.

I do have to disagree-not disagree with Ruthanna a bit on how Blackwood handles race. You’ve commented before on the conflict that arises in a lot of these stories as a result of the author trying to have it both ways in terms of criticising the lower classes for their quaint superstitions, while at the same time having those superstitions be entirely justified. Blackwood deals with this clash a lot better than many others. After all, of the four characters other than the unfortunate Défago, it is Punk who comes up with the most sensible response to the situation by simply getting the hell out of Dodge at the first opportunity (the description of Punk’s appearance that you quote says as much about Simpson’s ignorance and naiveté as anything else). And of the three British types, it is the less educated Davis who comports himself best as a result of coming to terms with what’s going on while the other two are still trying to rationalise it all away. Sure, it may be Uncle Cathcart who gets the most expositionary dialogue, but mostly he’s just Dunning-Krugering his way through it all.

I definitely disagree with Anne that the idea that the wendigo subsists on moss somehow undermines its effect. As someone who’s been at the wrong end of a bull charge, I can attest that something doesn’t have to want to eat you to be terrifying.

@1 You know, it’s odd you should say that, because I came into this thinking I had read this story before, and while bits of it were definitely familiar, I was completely wrong about what happened at the end.

I remembered the guy being dragged off into the air while screaming about his feet burning, but I was thinking he was never seen again until years later when one of the others came across him sitting wrapped in a blanket, but when he looked inside, there was nothing but a pile of ash. So, either there’s another version of this story floating around somewhere or another story almost exactly like it, except the ending. I don’t think I imagined it, I don’t think I could come up with something that specific, or that bizarre.

@6 I almost think it’s worse if they aren’t trying to eat you, because at least the impulse to feed is recognizable and understandable.

Agreed. My favorite parts of this are the scattered paragraphs of austerely beautiful imagery; my least favorite were the random bits of racism.

Children of the Great Muskeg, a fine anthology of poems, stories, nonfiction, and art by Cree and Metis children at the south end of Hudson Bay, includes three poems and a drawing describing a windigo (their spelling). Each describes it differently, with some nice similes, but there are some similarities — a big, ugly, hard-hearted biped with a deep, loud voice and horrible breath. The only other depiction I’ve seen was in novels by Louise Erdrich, where they were Ojibwe (IIRC) spirits of hunger which could take the form of humans or, in one case, a dog.

I live in the town of Ithaca, NY, so can think of nothing else when I see mention of “Ithaqua.”

@anne: Vast cornfields (like other flat landscapes) have always creeped me out, as I’m accustomed to the vertical diversity of wooded hills. And then The Omnivore’s Dilemma made them more terrifying to me than any fiction ever could.

@7 “I remembered the guy being dragged off into the air while screaming about his feet burning, but I was thinking he was never seen again until years later when one of the others came across him sitting wrapped in a blanket, but when he looked inside, there was nothing but a pile of ash.”

That is the version that I’m sure many of us know and love/hate from the “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” books.

@10 That would explain a lot, actually. I know I read those books as a kid. And I was kind of leaning towards “expurgated version from childrens’ scary story anthology” as an explanation for the discrepancy.

“Then I thought it was the one where one of the hunters treats the Native American

guide horribly, tracks a wounded moose (or was it a bear?) into a weird lost

valley/Peaceable Kingdom where he transforms into a beast, and then the guide comes

back and rescues everybody with his mystic native powers.”

@DemetriosX, that was “Valley of the Beasts” and it was by Algernon Blackwood.

There’s an audio book version (with terrible voices) on Youtube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CuYH7caNL84

Joseph Payne Brennan’s work seems to have become collectors items, judging from the

prices on Amazon.

I really hope that when the author says Punk looks no more like a real Indian

than “stage negros” look like real Africans, he’s not referring

to minstrel shows. His portrayal of the Indian is bad enough as it is: note how the

group is referred to as a party of four…plus the Indian.

“From the ruins of

the dark and awful memories he still retains, Simpson declares that the

face was more animal than human, the features drawn about into wrong

proportions, the skin loose and hanging, as though he had been subjected

to extraordinary pressures and tensions. It made him think vaguely of

those bladder faces blown up by the hawkers on Ludgate Hill, that change

their expression as they swell, and as they collapse emit a faint and

wailing imitation of a voice.”

Man, what old photos have taught us is true: people did have the creepiest tastes in

entertainment back before WWI.

I wonder what the exact connection is between “monster Defargo” and the “normal”, if

totally mad one who appears at the base came. Perhaps Defargo is being worn for a

while…

DemetriosX @@@@@ 1: He seems to know and love nature enough to be afraid of it. A very sensible attitude, really, especially writing in a time when humans were still in more danger from nature than the reverse. Even now, people with much love but less sense hear the “call of the wild” and get themselves carried off, on burning feet or otherwise. A friend’s stories about stupid things people do in the Alaskan wilderness spring to mind…

SchuylerH @@@@@ 2: Lovecraft and I clearly have very different taste in prose. Which, I suppose, comes as no shock.

ChristopherTaylor @@@@@ 6: There are different levels and types of prejudice. Positive or neutral stereotypes aren’t as bad as hatred and fear–but they still do harm, and are still no fun to read about if you’re the one being stereotyped. Especially if something that your culture values teaching is glossed as inborn instinct.

Agreed about the moss-eating–to me, that actually made it creepier. It’s not that the Wendigo harbors any malice against you or even finds you tasty. It really and literally is a force of nature. And it can outlast you, because it can live on something that won’t sustain a human.

AeronaGreenjoy @@@@@ 9: Cornfields, mountains, seaside towns… you can find good justification for setting a horror story anywhere. But I too vote for cornfields as legit scariest.

Bruce Munroe @@@@@ 12: I suspect he’s totally referring to minstrel shows. I can’t think of any other explanation, and the timing is certainly right.

Bruce @12: Good to know my brain hasn’t entirely turned to cheese. What I remembered certainly felt like a Blackwood story. Thinking about it some more, I think the other story I mistook for this one ended with the protagonist laying the ghost of a murdered Indian to rest (in a respectful, giving him peace sort of way). Pretty sure that was Blackwood, too.

Ruthanna @13: I think being afraid of the wilderness is just as likely to get you killed as underestimating it. A healthy respect is the right attitude, and Blackwood’s outdoorsy stories seem to reflect that attitude. He just cranks things up a notch for the purposes of the tale. He worked as a dairy farmer in Canada, which is probably where this and a few other stories came from. And his love of the outdoors seems to have been genuine, since he requested that his ashes be scattered in the Alps.

Where I live cornfields aren’t so much scary as outright dangerous. They attract wild pigs and those things can screw you up big time. I know what to do if I run into a wolf or a lynx, but with a wild pig all you can really do is run like hell and hope it doesn’t feel like chasing you very far.

For me the setting that gives me the willies is cool, green, shady and slightly damp corners of gardens. Almost everywhere I’ve ever lived there’s been a corner of the garden like that that I just can’t make myself go anywhere near.

Now I think about it, I seem to recall Algernon Blackwood himself making a cameo in Rick Yancey’s “The Curse of the Wendigo,” which featured a somewhat more traditional iteration of the monster, as a cannibalistic Spirit of starvation. In spite of that, it seemed like by including Blackwood as a character, the author was suggesting the events of the book inspired Blackwood to write his Wendigo story–which, to be honest, made me wonder if Yancey ever actually read Blackwood’s story, because they have virtually nothing in common.

That’s not to say anything against Yancey’s “Wendigo,” I really enjoyed it. It was gory and horrifying in the best ways horror can be–not just physically horrifying but deeply disturbing on a psychological level, too. I’d be interested to know if anyone else here is familiar with it.

A very good commentary by both authors. I came across this page while looking for pictures (depictions) of the Manitou for a drawing that I was working on. I have read several of Blackwood’s short stories and found them delightful. I will seek out this story and I thank you for your excellent observations on this great horror author.