Hi—my name is Alasdair, and I love time loop episodes. When done right, they’re a brilliantly efficient piece of storytelling, using the repetition of events and the accretion of knowledge to not only show us more about the characters but often give the writers a chance to have a little fun (and maybe let the production office save a little money). For years, my platonic ideals of this story have been “Cause and Effect” from Star Trek: The Next Generation and “Window of Opportunity” from Stargate SG-1. The former has the best pre-credit sequence ever (Ship explodes! Everyone dies! Cue the music!). The latter has O’Neill and Teal’c trapped in a loop which leads to wormhole golf, a magnificently terrible yellow sweatshirt, and a moment that made fans of a certain ship gleefully punch the air.

Both are immensely fun hours of TV, and recently they’ve been joined among my favorite time loop episodes by three more excellent examples of the form at its absolute best. Here they are:

Star Trek: Discovery

Season 1, Episode 7: “Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad” (Written by Aron Eli Coleite & Jesse Alexander)

When the Discovery takes aboard a Gormagander—an incredibly rare space-going whale-like creature—they get an unexpected passenger: Harry Mudd. Intent on taking vengeance on Lorca for leaving him to die, Mudd has both a plan and a device that allows him to loop time until he gets it right. The only problem is, one of the Discovery crew doesn’t really perceive time the same way everyone else does…

This was the episode where Discovery really found its feet for me, and it remains a season highlight, as well as a Hugo finalist. The fact that it stands out isn’t just due to the time loop plot, either, although that does a really effective job of contextualising Harry Mudd, calling attention to Lorca’s plot, and advancing basically every central narrative of the show. Burnham and Tyler’s romance in particular really works here, as well. It feels real and cautious and complicated (and that’s even before we learn more about Tyler’s true nature in a later episode).

But what’s really memorable here is the way the show takes a very familiar approach to telling its story and then cheerfully refuses to do what you expect with it. I love that Burnham is our POV character but Stamets is the one who the events—but not the story—center on. I love that the situation is resolved by giving Harry exactly what he thinks he wants in a manner that both sets up and provides a framework for his future appearances. Most of all, I love that we get to see a Starfleet crew relax and find that they do so at the same kind of endearingly rubbish, overly enthusiastic parties we’ve all been to at one time or another. After six episodes of appearing as a bunch of slightly grim people in flight suits, in this episode the crew suddenly feel like real, relatable people.

Best of all, though, is the emotional narrative. By building the time loop into the core of the story, the writers are able to ground events in personal experience rather than technobabble. Tyler and Burnham dancing together for the first time is sweet. Stamets and Burnham holding hands as the loop ends again is touching. But Burnham’s moment of self-knowledge, and how she uses it to speed up her reactions in the next loop is what really gets you. Personal, heroic, painfully honest, and one of the moments in the first season where the character really clicked—topped off with some witty, poignant musical cues that riff on the show’s theme—this episode is a real winner.

Cloak & Dagger

Season 1, Episode 7: “The Lotus Eaters” (Written by Joe Pokaski & Peter Calloway)

Tandy discovers that Ivan Hess, a colleague of her father’s, survived the rig explosion but is in a coma. With Ty’s help, she gets through to him and they both find themselves stuck in Hess’ mind, endlessly repeating the final seconds before the rig blew up…

Cloak & Dagger’s first year ranks among the best television that Marvel have produced to date, and this is its finest hour by a good distance. Like “Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad,” it accomplishes this by structuring the episode around the time loop and using it to do as many different things as possible. That includes moving Tandy’s main plot arc along, giving her a handy training montage, forcing her to confront her feelings about her father, and reinforcing to both Tandy and Ty that they work best as a team. At the same time, it sets up some of the bittersweet and flat-out horrific elements of the next couple of episodes, as we see Tandy watch the Hess family reunite in the exact way her own family can never do.

Best of all, this actually feels like a story about a pair of superheroes learning who and what they are. Ty’s arc gets short shrift after the last couple of episodes but that ties cleverly into the compromise they both have to make in order to work together, and neatly sets up his arc-heavy episodes to come. Plus the episode cleverly cements Ty’s role as the moral compass of the pair, and his decision to go back into Ivan’s mind when Tandy refuses to leave is a vital part of his heroic journey.

For her part, this is Tandy’s finest hour. She channels her need for vengeance into a desire to help someone caught in almost exactly the situation that’s broken her. She does so altruistically, and accepts that what Mina and her father have will forever be denied to her. What she doesn’t see, and can’t know, is that the idealised version of her father she still clings to is the furthest possible thing from the truth. So, just as Ty continues to rise, Tandy crests and begins to fall. It’s complicated and nuanced emotional storytelling, and much like Discovery’s time loop narrative, it sets the tone for the show’s future. And just for the record, anything which gives Tim Kang (who plays Ivan Hess) a chance to show off just how damn good he is?—that’s fine with me.

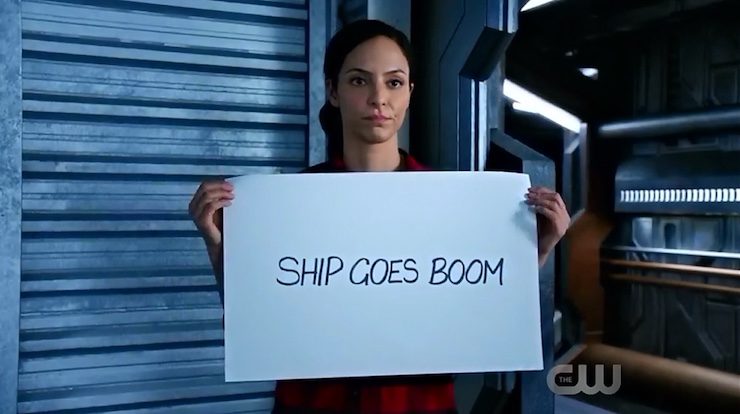

Legends of Tomorrow

Season 3, Episode 11: “Here I Go Again” (Ray Utarnachitt & Morgan Faust)

The team come back from a mission in the ‘70s to find two things: that Zari’s experimentation may have broken the ship. And…well…time. Even more so than they already have.

Legends of Tomorrow’s third season is immensely good fun. Whether it’s Neal McDonough fighting himself, the world’s most meta John Noble joke, or an ending that is so, SO stupid that it actually comes out the other side into brilliant, the show had a great third year.

Buy the Book

Alice Payne Arrives

This was the best episode of the season for me, because, like the two stories mentioned above, it uses the central mechanism of the time loop as a storytelling engine rather than a destination. Over the course of the episode, not only does Zari slowly realise that her team are much more complicated people than she thought, but the real focus becomes her acceptance of her place with them, even to the point of being willing to die for them. The Legends are history’s greatest underdogs at the best of times, but seeing them as people, not punchlines—as we do in “Here I Go Again”—makes them something more: it makes them truly inspiring. Mick in particular, who is revealed here to be a surprisingly good novelist, gets some welcome character development. He growls a bit about it (because he’s Mick), but it’s still sweetly handled, touching stuff.

Perhaps the strongest aspect of this episode is how it digs into the cost and stakes of this situation. The sheer weight of knowing how long they have left to live and being unable to do anything about it almost breaks Zari. Tala Ashe, whose fantastic deadpan comic timing shines throughout the season, is just as good when facing the grim side of things, and her performance makes us feel the weight of the hours she’s lived. But she’s also able to show us the impish side of Zari, thanks to Nate. Nate and Ray, who brilliantly know exactly what’s going on pretty much the second she tells them, give the show the winking, meta-fictional foundation it needs (See Nate’s “It was only a matter of time before we did one of these!”). It’s in capturing the more earnest, human side of the situation, however, where all three shine, representing the show at its best: Ray with his puppyish enthusiasm, Zari with her sense of humour, and Nate with his fundamental decency and compassion. The result is funny, sweet, and immensely weird, as only the Legends can be.

Time loop episodes are too often viewed as just an exercise in box-ticking, or a fun gimmick with little consequence in terms of plot development. But, as these three episodes show, when done well, a time loop structure can function as a lens that changes how viewers see the show. Just as the characters gain a new perspective on their lives, so do we. The overall effect is less like a loop and more like a slingshot, catapulting viewer and show alike into a different, more nuanced and interesting orbit.

And of course, on occasion, wormhole golf sometimes happens, and that’s always a good thing.

Alasdair Stuart is a freelancer writer, RPG writer and podcaster. He owns Escape Artists, who publish the short fiction podcasts Escape Pod, Pseudopod, Podcastle, Cast of Wonders, and the magazine Mothership Zeta. He blogs enthusiastically about pop culture, cooking and exercise at Alasdairstuart.com, and tweets @AlasdairStuart.

Glad to see Legends on here! Her name is Zari, though, not Zuri.

@1 – Fixed, thank you!

The entire latest season of Agents of SHIELD was built around a time loop. Generally, I don’t care for them, because all the mayhem gets undone at the end, which tends to undercut any sense of jeopardy.

This is the first description of Star Trek Discovery that has made me actually want to watch the show!

Probably my favorite time loop ever is from an anime, and even naming the anime at all is a spoiler, so highlight to read:

//

Madoka Magica’s timeloop, especially the episode in which it is revealed (EP 10, I think?) is brilliant, and moving. One of my favorite anime episodes of all time, although it requires the previous episodes as buildup.

//

Also shout-out to “Window of Opportunity” from Stargate SG:1, still one of my favorite scifi episodes of all time

My current favourite is from Travellers — where the time loop is set using the limitations of the existing time travel for the show.

I’m not really a fan of time loop stories, both because the repetition annoys me and because the physics make no damn sense (which is true of most time travel stories in general). But in recent years, people writing time-loop stories seem to understand that the audience is used to the trope, so they don’t waste time on the first few repetitions but just jump right into the meat of the story where somebody’s already in on the loop, and they make sure each loop is quite distinct from the others, so I’m finding them less annoying than I used to. Syfy’s Dark Matter did this effectively in “All the Time in the World,” episode 4 of season 3.

Also, it seems we’re getting more episodes lately where the so-called “time” loop turns out to be a simulation or a dream rather than an actual time-travel event. It was openly a coma patient’s repeating nightmare in the Cloak and Dagger episode, and I can think of two recent examples where it was a computer simulation (in one case a VR game where the viewpoint character was simply respawning when he died), though naming them would be a spoiler.

I’m not a fan of “Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad,” because turning Harry Mudd into a cold-blooded mass murderer does not make any damn sense and makes it impossible to continue seeing him as a harmless, comic nuisance like he is in TOS and TAS. Sure, I’ve seen it argued that he knew the killings would be undone by the time loop so nobody would really be hurt, but that ignores the particularly cruel and sadistic murder he committed at a point where he believed he was already out of the loop, and which was only undone because he was manipulated into looping one more time. So he intended that murder to stick, and it was by far the most horrific murder in the episode. I just can’t reconcile that with Stephen Kandel & Roger C. Carmel’s Harry Mudd.

Doctor Who’s “Heaven Sent” should really be on here, even though it’s not technically a time loop I guess, since time keeps moving forward, but from the Doctor’s perspective it mostly is.

Time loops are about the people living them, particularly the one who knows he/she is in the loop, not the events. Otherwise, it’s a giant case of “never mind.” That’s why we love some loops, but others are infinitely forgettable.

@8/Alex K: As I said, a lot of time loop stories these days involve simulations or dreams rather than actual time travel. The category is defined by the story mechanic of the character(s) being trapped in a repeating cycle of events and having to figure a way to break out of it, regardless of the true cause of the repetition. The most famous example, often used as the namesake of the trope, is Groundhog Day, although the makers of that film were accused of plagiarizing the idea from Richard Lupoff’s 1973 short story “12:01 PM” and the short film and TV movie that were made from it.

So the Agents of SHIELD example mentioned above doesn’t quite fit, because it was just a single extended loop spanning the entire season, although we were told that there had been multiple prior repetitions of it. And Travelers doesn’t fit at all, because it’s not a repeating or recursive time loop, just a regular time travel story where the time travelers’ actions in the past alter the future they came from.

@8. Alex K: “Heaven Sent” is mostly amazing, but also frustrating. You could look at it as a virtual reality experience, since he’s stuck inside the Dial. But damn it man, at least bring the shovel to chip away at the mountain of 400X harder than diamond stuff. Doing it with his fists was ridiculous. Even the billions of years the episode said it took should’ve been impossible. Skin and bones do not break diamond.

But it was an effective metaphor for grief, following the harrowing demise of Clara in the previous one. It effectively set up that the Doctor was willing to do anything to restore her, even ruin time and space.

Futurama finale “Meanwhile”.

What about that show a few years ago where a guy stepped out of the shower and realized it was all a dream? Did that count as a time loop?

@13/AlanBrown: That was Dallas, it was 32 years ago, and no, it wasn’t a time loop, it was a retcon. Patrick Duffy had left the show at the end of the 8th season, so they killed his character off. Then he came back a year later, so they retconned the entire 9th season as his wife’s dream (which created continuity snarls for the spinoff Knots Landing, which ignored the retcon).

And again, I think we should keep in mind the distinction between a time loop that happens once (like when TNT’s Witchblade reset the timeline back to the beginning at the end of season 1) and the particular type of time loop story being discussed here, a loop that repeats many times within a single episode. Those are two very different categories of story. A single time rewind is just a way to reset the continuity. A repeating loop is a trap that the characters need to find an escape from, and that tends to be especially harrowing for the characters due to the nightmarish inevitability of the repetition.

@13 If you are thinking about the original DALLAS which was considerably more than a few years ago, the scene was a soft reboot of the series after the writers killed a character then brought him back to save the ratings. He stepped out of the shower, and his wife realized that his death and the last season was a bad dream. That’s bad writing, not a time loop.

Another fun recent example: HAPPY DEATH DAY, a very entertaining horror comedy that applies the time-loop to a slasher-movie scenario. College coed keeps getting murdered night after night, no matter how she hard she tries to change the scenario. Can she break the cycle by uncovering the identity of the masked killer?

Very cleverly done–and more funny than gory if that’s an issue.

“White Tulip” from Season 2 of Fringe

One of my all time favourites is ‘Been There Done That’ from Xena!

Sunspear@11: The Doctor didn’t know about the diamond wall, in any of the repetitions, until it was too late to get any tools.

@7/CLB,

FYI, a cold-blooded mass murderer being turned into a harmless, comic nuisance – I’d say that pretty well sums up Neegan from The Walking Dead.

@20/Keleborn: It’s more a case of a relatively harmless comic nuisance being retroactively portrayed as a cold-blooded murderer a decade earlier in his life.

@21/CLB,

Well, yes. And I can understand how you would object to that. In fact you’ve returned me to my previous state of not exactly being in a hurry to see Star Trek Discovery – I’ll wait for the Library DVD, possibly years from now.

@19. David: Yes, but that’s the flaw in the Ep for me. Instead of writing “bird” in the ashes, write frigging “shovel.” You’d lose the poetry, but speed things along considerably.

Of course, it still works as an extended metaphor for grief and refusing to accept a loss.

@22/Keleborn: It was announced recently that the first season of Discovery will be out on DVD and Blu-Ray on November 13. Anyway, I was talking about just one episode, so you shouldn’t judge the season as a whole from it.

The show 12 Monkeys has a number of great time travel episodes but they have one called Lullaby that is a brilliant take on a time loop.

I’ve never thought about it much, but in considering the examples discussed here (plus a few others not mentioned) it strikes me that focusing on time travel’s value as a narrative device is the key to using it succesfully in a story (at least in those where it isn’t otherwise part of the basic premise). Reset loops are great for exploring character and the consequences of choice, while Stable Time Loops can be useful for getting a broader perspective on the story while utilizing the existing POV characters. But handwaves and sparing use are crucial: get too far into the details of time travel itself, or, worse, use it as a cheap way to resolve an inconvenient plot snarl, and you’re likely to run into some trouble.

@7/CLB: So, you’re just dandy with the physics of FTL and transporters, but time travel is beyond the pale? That’s rather…selective. ;-) Actually, though, those two also probably work best when used as structural shortcuts rather than major plot points. SF as a genre seemed to develop useful tropes for incorporating those concepts relatively early on—perhaps drawing upon examples from theater, where large jumps in space or time (usually only forward) from one scene to the next have been the norm for centuries? Maybe writers are finally getting the hang of how to deal with time travel in a similar fashion.

I’ve only seen the Legends episode out of the three, but I really liked that.

@7 ChristopherLBennett That Dark Matter episode is the one I think of whenever I get irritated that the show was cancelled. I agree that they handled it well.

Just a decade ago, Supernatural did it with the episode Mystery Spot.

@26/Ian,

Your comment just made me remember the 2017 film “Before I Fall”, where a time loop was used for strictly narrative purposes. One of 3 teenage girls who are friends dies in a car accident, then keeps getting looped back into maybe a day before the accident. All three girls are rather annoying and immature, but only the one who is aware that she is caught in a loop begins to evolve. What surprised me was that seeing the other two girls continuing to be annoyingly immature in loop after loop (being you might say stuck in a loop), I nevertheless began to feel some sympathy and even liking for them, just as they were in all their annoyingness. I didn’t think of this film at first because it has no sf-ness; its more like a darker version of groundhog day.

@26/Ian: “So, you’re just dandy with the physics of FTL and transporters, but time travel is beyond the pale? That’s rather…selective. ;-)”

No, because it’s based on the specifics of each case. It’s not arbitrary. I have no problem with a time travel story that takes care with the physics and logic of the idea, e.g. Robert L. Forward’s novel Timemaster. The problem is that there are so very few of those. Any SF concept can be handled with greater or lesser degrees of plausibility, but the reason I don’t care for time travel stories is that they’re almost never done plausibly. Most of them are wish-fulfillment fantasies that completely fall apart if you really dig into their underlying logic. Especially any story based on the premise that a new timeline would “erase” or “overwrite” the original, which is a fundamental contradiction in terms. Change or erasure requires a before and an after — one version follows the other. But a single moment in time cannot come after itself. The perception that it does is an illusion created by the time traveler’s revisitation of that moment, like rewinding a tape. If there are two versions of a single moment, then by definition they are simultaneous, not consecutive. So a new timeline doesn’t “replace” the original; it exists alongside it in parallel. So any story that shows a timeline being rewritten or altered — especially in the ludicrous Back to the Future way where the characters can actually see the change happening — is utter fantasy. But “changing history” is more dramatic than parallel timelines, because the stakes are higher if the world you know is in danger of being erased, so that’s the approach that’s usually favored in time-travel fiction, even though it’s an utter impossibility.

And Groundhog Day-style time loop stories — which, yet again, are their own distinct category from other flavors of time travel story — are even more of a logical muddle, because they require the absurd premise of a single moment in time coming after itself, not just once but multiple times. The idea of time somehow looping back on itself for every character save one who manages to keep moving forward in their perceptions is easy enough to imagine as a narrative, but there’s no way to make physical sense of it. Well, I barely managed to find a way in my novel Star Trek: Department of Temporal Investigations — Watching the Clock to rationalize the physics of the time loops in the first-season TNG episode “We’ll Always Have Paris,” but it required delving into some incredibly abstruse temporal theory involving multiple dimensions of time, and it still wasn’t very convincing.

@29/Christopher: Doesn’t time travel presuppose two different layers of time? The universe’s time becomes something the time traveller can walk around in (taking the time-as-space metaphor literally). But the time traveller’s time (which has to be distinct from the universe’s time, or she wouldn’t be able to travel in time) remains the ordinary one-thing-happens-after-the-other. So when a time traveller changes time, there is “before” and “after” only for her – from the point of view of the universe, there is still one universe, comprised of many moments following one after the other.

I have no idea if this makes sense physically, but I find it philosophically plausible.

@30/Jana: No. The time traveler’s perception that the same event happens twice is an illusion created by the time travel, like rewinding a tape. If you rewatch a sporting event on your DVR, it doesn’t mean the outcome can be any different. As far as the universe is concerned, it only happens once, and the time traveler is simultaneously present in two incarnations.

Of course, all observers’ perceptions of the flow of time are relative to their frames of reference, which is how time travel can theoretically exist at all. But causality has to remain consistent. There’s nothing in the laws of physics that precludes an effect coming before its cause, since it is all relative. But the chain of cause and effect has to happen in a mathematically unitary way — that is, any interaction must have a single, knowable result, or the laws of physics break down. If something happens, then it happens, period. It’s part of the universe, part of the overall chain of cause and effect regardless of the order it happens in, and thus it can’t be “erased” from reality. The only way a single event can happen two or more ways is if they all happen in parallel timelines. Even if it looks to the time traveler as if one has “replaced” the other, that’s a subjective perception arising from the time traveler’s movement from one timeline to the other, and that one person’s perception does not outweigh the rest of reality. Step back and look at the universe as a whole, and you see both timelines existing side by side all along. That’s the only way it can actually happen, physically, mathematically, and logically.

@31/Christopher: I don’t think that it can actually happen at all. It just seems possible to us because we’re so used to conceptualising time as space.

That said, I prefer my time travel stories to be of the “physically, mathematically, and logically” impossible kind, because I have serious philosophical issues with the others. If the timeline is immutable, everything is predestined, and choice is an illusion. If there’s a multitude of timelines, everything happens anyway, and choice is meaningless. That’s not how I see the world.

@32/Jana: “I don’t think that it can actually happen at all. It just seems possible to us because we’re so used to conceptualising time as space.”

You’ve got this backward. The reason we’ve learned to conceptualize time and space as facets of the same thing is because Einstein figured out that they actually are, that what we think of as time is in fact one of the four dimensions of spacetime. That’s not a belief or a metaphor, it’s an outgrowth of the mathematics devised to explain real scientific observations and make predictions which have been extensively confirmed by countless experiments over the past century. The reality of the Einsteinian model of spacetime has been proven by the discrepancies in the orbit of Mercury, by the time-dilation corrections necessary to make GPS/satnav calculations work, by countless other observational and experimental confirmations. General Relativity is a correct (though incomplete) description of the universe. And the equations of General Relativity predict that in certain extreme conditions, such as those found within the ergosphere or singularity of a rotating black hole, spacetime would distort in such a way that “spacelike” and “timelike” axes would be inverted — in essence, time would behave like space, allowing motion through it both directions.

But what I’m saying isn’t even about that. The point is about whether a story even makes any logical sense within itself. Even a fantasy story should be self-consistent according to its own internal rules. But if you dig down into most time travel stories, really analyze their internal logic in detail, you usually run into a self-contradiction, an irresolvable paradox or absurdity that makes the logic of the story fall apart and that you have to ignore if the story is to work. In real physics, time travel would require a black hole or a wormhole; but in fiction, it almost always requires a plot hole.

“If the timeline is immutable, everything is predestined, and choice is an illusion. “

I see it the other way around: That the lack of free will is an illusion created by time travel. Go back to my “rewind the tape” metaphor. If you watch a replay of a sporting event, you know that the outcome will be exactly the same as it was last time, and that creates the illusion that the outcome is predestined. But it wasn’t. It’s just that it already happened. Time travel can make it look as though an event has a second chance to happen, but that’s an illusion. We do have freedom of choice, but we only get to make each choice once.

Another way of looking at it is that our freedom of choice depends on our circumstances, on the degrees of freedom permitted by our environment and situation. If you’re standing in an open field, you have the freedom to choose any direction in which to move, albeit only in two dimensions. But if you then fall off a cliff, your freedom to choose your direction of motion becomes enormously more constrained. By the same token, in an immutable timeline, a time traveler’s freedom to influence events around them would be far more constrained than that of someone moving through time normally. The restrictions on the time traveler’s freedom to act are not generalizable to everyone else, because the time traveler exists within conditions radically different than those of a normal person.

“If there’s a multitude of timelines, everything happens anyway, and choice is meaningless.”

This isn’t actually true either. Quantum multiverse theory doesn’t require every possible outcome to occur; it merely says that the total wave equation of the universe is a sum over multiple distinct states. It also applies to changes in quantum particle states and thus has nothing to do with human choice, despite the way fiction tends to interpret it. Since the mechanisms in the brain that we use to make decisions are on a macroscopic scale and thus follow classical physics, they shouldn’t be affected by quantum multiplicity. No matter what timeline you’re in, you’ll make the decisions that arise logically from your circumstances and needs. If you have a reason to turn right, all the quantum fluctuations in the universe won’t make you randomly turn left. Maybe those quantum divergences would create the opportunity for humans to make different choices if they’re on the fence and could go either way, but most decisions aren’t just coin flips; we make them for specific reasons that wouldn’t randomly change. So the number of different paths that people’s lives could follow would still be finite and would tend toward the most likely outcomes.

So if someone goes back in time and thereby creates a parallel timeline where events happen differently (alongside the original timeline where they happened the original way), then that change is specifically because of the time traveler’s actions and their macroscopic influences on people and events. It doesn’t mean that every decision in the universe is made in every possible way.

I also like the Legends of Tomorrow episode the best out of these, even though the show on average is mostly goofy. I’ve always found Tala Ashe to be gorgeous, but this was the first episode that I started appreciating Zari. This was a great fast forward way of turning her from a cynical tag along to part of the crew.

@33/Christopher: “You’ve got this backward.” – No, I don’t. I wasn’t talking about Einstein. I was talking about the fact that humans think about time in spatial terms. It’s in many languages – terms like “time span”, “point of time”, things taking “long” or “short”, the idea that the future lies before us and the past behind us, etc. Linguists and cognitive scientists call this “spatial time” or “the time-is-space metaphor”. It has nothing to do with actual spacetime.

Concerning free will and predetermination, the crucial point is that in order to have free will, the future must be open (another spatial metaphor). If I can visit the future or the past, I can make choices, but seen from the outside, everything is fixed. If time travel is impossible, the view from the outside becomes impossible, because the future doesn’t exist yet. If I can change the future, I have it both ways – it’s possible to see the future from the outside, but it isn’t fixed.

You may be right about the multiple timeline hypothesis. I have to think about that one.

@33/CLB,

If in a rotating black hole, the spacelike and timelike axes become inverted, does that mean that under those conditions space has only one direction?

Let me guess. It’s down. :)

@35/JanaJansen,

Everything is predetermined. You’re free to decide how you feel about that. :)

@CLB: While the things you are saying about time and causality are true, I fail to see how they establish time travel as particularly more impossible than the other sorts of impossible physics found routinely in SFF.

Now, I think you bring up an interesting angle in that the types of potential inconsistencies inherent to time travel are likely to be more obvious to both characters and audiences than the more esoteric issues associated with, say, relativity or quantum physics, and so writers really should do a much better job of addressing them (if even just to handwave them away). Yet it is still a subjective choice to focus on this particular trope when the same degree of scrutiny could be applied to many other aspects of the stories in which it typically appears. By all means, call out poor writing! But make sure to own your Flying Snowman, and don’t claim your complaints are because the physicists demand it. :-)

@35/Jana: “I was talking about the fact that humans think about time in spatial terms.”

And you said that was the only reason people believed in time travel. My point is that it isn’t — the possibility of time travel emerges from the equations of General Relativity. That’s not human belief or bias or metaphor, that’s the actual laws of nature as discovered through observation and experiment. There are actual equations and theoretical models that allow for the possibility of time travel, emerging both from GR and from quantum physics. Of course it’s prohibitively impractical, since it would require extreme conditions like black holes and would most likely destroy any macroscopic object that attempted to pass through a time warp, but we have a fairly solid theoretical understanding of how time travel would work if the practical obstacles could be surmounted.

“Concerning free will and predetermination, the crucial point is that in order to have free will, the future must be open (another spatial metaphor). If I can visit the future or the past, I can make choices, but seen from the outside, everything is fixed.”

From your perspective; not from another’s. The whole reason relativity is called that is because it established that there is no single, universal, absolute description of the universe — the universe you perceive is relative to how and from where you observe it, and the perceptions of observers in two different frames of reference can contradict each other yet both be equally correct descriptions of reality. So if one observer sees a fixed reality and a different observer sees a reality that they can choose and shape, neither one is wrong, and neither one’s perception can or should be assumed to apply to the other. Both of them are right, relative to their particular frames of reference.

Besides, free will is always limited. Nobody ever has absolute freedom of choice. We only have the freedom to choose among the viable options available to us in a given situation, and some situations offer more options than others (as in my “fall off a cliff” example). So to speak of “free will” as a single, universal constant, as something that either exists absolutely or doesn’t exist at all, is ridiculous. It varies from case to case, from person to person. So one person’s lack of freedom does not prove that nobody has freedom. It’s a basic logical fallacy to mistake a specific case for a general case.

Anyway, quantum physics basically says that the future is already defined in the wave equation of the universe, that past, present, and future all already exist, but knowing that equation would require exact measurements of every particle in the universe, and there are physical limits on our ability to gain that much knowledge (e.g. the Uncertainty Principle, among other things). So in that sense, our free will resides in the gaps in our knowledge — we can’t know what the outcomes to all our choices will be, and that’s what gives us the freedom to choose them. That very act of choice may be woven into the fabric of the universe along with everything else, but that’s exactly why I think the choice does matter. Maybe there’s only one way we can end up making it, but that doesn’t mean we have no say in it; on the contrary, it means our say in our decisions is an integral part of what shapes the universe. Our choice in a given moment is the end result of every prior choice in our lives and every prior circumstance shaping that moment. So it’s not arbitrary; it’s the logical outcome of everything that led up to it, including our prior life experiences and choices. And what we choose in that moment is part of what leads to the next outcome, and the next.

@36/Keleborn: “If in a rotating black hole, the spacelike and timelike axes become inverted, does that mean that under those conditions space has only one direction?”

Well, that part always confused me a bit, since there are of course three dimensions of space, not just one. It might only be in one of those three dimensions that you’d be required to move in a single direction. But you’re probably right to say it’s “down,” if “down” is defined as the direction toward which the gravitational field draws you. The geometry of spacetime would be so severely warped by the intense gravity that there would be directions you couldn’t possibly move in without exceeding the speed of light.

@38/Ian,

Wait, if Snowmen could fly, wouldn’t air friction make them melt faster?

Oh, I’m in a silly mood today. Sillier than usual that is.

@38/Ian: “While the things you are saying about time and causality are true, I fail to see how they establish time travel as particularly more impossible than the other sorts of impossible physics found routinely in SFF.”

Like I said, it’s about the internal logic of the stories and the self-contradictions that you almost invariably run into if you really try to dig into the cause and effect. Time travel stories tend to be more centrally about logic and causality than most other kinds of story — if I do X, it leads to Y result, and if I don’t do X, it leads to Z result. So they invite more attention to the causal logic of their events, yet I’ve rarely encountered a time travel story where that causal logic didn’t have a big handwavey leap in the middle of it somewhere.

It’s different from a story with, say, FTL travel, since the FTL is usually just a means to get the characters to the story, rather than a key component of the story logic itself. There are some stories where the actual mechanics and operation of the FTL is important, and if such a story centered on a major logic hole or contradiction, that would be a problem for me. But that would only be the case in a small subset of the stories that used the idea. Time travel stories are different because they usually have that kind of hole in them somewhere, when they aren’t just pure fantasy.

@39/CLB,

On a serious note, I was actually thinking that this kind of inversion of space to become timelike in the presence of a black hole, in the sense that there is effectively only one direction the photons can go, is precisely symptomatic of being a trivial artifact of the mathematics. I am guessing that these conditions “exist” right down at the bottom of the gravity well – in the mathematical sense.

Not that I claim to have an understanding of General Relativity. I actually gave it a go once, and even now still have Burke’s Spacetime Geometry on my shelf, but no … it’s not gonna happen.

Addendum: is there a “layman’s explanation” for why the black hole has to be rotating? And does this mean that Newton was wrong, that one really can define absolute rotation?

@42/Keleborn: But the spacetime metric I’m talking about isn’t just falling straight into the singularity. On the contrary, it’s a topology that exists around the edges of a rotating black hole (or a massive rotating cylinder in the original Frank Tipler paper). Basically the dense, rapidly rotating mass “drags” spacetime around it, a phenomenon called frame-dragging or gravitomagnetism (because it’s basically to gravity what magnetism is to electricity, arising in the same way and following essentially the same math). This frame-dragging is what inverts the spacelike and timelike axes, because it drags your light cone (the range of paths you can follow in spacetime without exceeding the speed of light) sideways until it overlaps the time axis. This all creates a sort of oblate “shell” of inverted spacetime around the black hole, and it’s by following the right path through that region (the ergosphere) that you can end up on a closed timelike curve (i.e. go back in time).

It is true, though, that the singularity inside a rotating black hole would take on the shape of a ring/torus (a Kerr ring singularity) rather than a point, and if the BH were large enough or your ship magically indestructible enough that you could pass through the center of the Kerr ring, it would basically be like a wormhole, sending you to a different part of spacetime, which could be another place, another time, or another universe altogether. (This was referenced in ST:TNG’s “Yesterday’s Enterprise,” with the time vortex described as “a Kerr loop of superstring material,” though they should’ve said “cosmic string.”)

“Addendum: is there a “layman’s explanation” for why the black hole has to be rotating?”

I think the frame-dragging/gravitomagnetism I discussed above is the explanation. No rotation means no dragging of spacetime axes.

“And does this mean that Newton was wrong, that one really can define absolute rotation?”

I don’t recall Newton saying that you couldn’t. But per Einstein, an accelerated reference frame is distinct from an unaccelerated one, and rotation is an acceleration.

@CLB: “In real physics, time travel would require a black hole or a wormhole; but in fiction, it almost always requires a plot hole.”

That’s a good line.

“That very act of choice may be woven into the fabric of the universe along with everything else, but that’s exactly why I think the choice does matter. Maybe there’s only one way we can end up making it, but that doesn’t mean we have no say in it…”

That is what Doctor Strange thinks he knows when he gives up the Time Stone.

Discussions like this are why I hate time travel

@43/CLB,

I wouldn’t exactly call that a layman’s explanation, but it certainly was a good one – to the degree that I can follow it. And it’s interesting to learn that those conditions exist sometimes outside the black hole.

I may have misunderstood Newton. I was thinking of the “rotating bucket” discussion.

Aren’t these kinds of stories typically meant to be more examinations of social constructs than anything scientific? That’s how I always take them at least, and because of that the time travel / looping for me becomes that one thing I have to accept for the novel to fall into place, and I prefer an author to just hand wave it away within a couple of paragraphs (you know, the time particles that were discovered in the 22nd century…). I can’t take novels that try to explain it all in terms of modern science because it never makes sense.

@39/Christopher: Of course free will isn’t “a single, universal constant” that “either exists absolutely or doesn’t exist at all”. Of course it’s always limited. It’s still a relevant question if it exists at all.

The distinction that our choices matter even if the future already exists and our choices are “woven into the fabric of the universe” is too fine-grained for me. I prefer situations and stories where the characters’ choices clearly and unambiguously make a difference. I’m simple-minded like that. Stories where the time traveller’s actions have always been part of the timeline can be fun (ah, this is how it all hangs together!), but they make me philosophically uncomfortable.

@48/Jana: Sure, and that’s actually part of the reason I’m not crazy about parallel-timeline stories myself, at least the kind that presume all alternatives happen instead of just some. There’s a difference between my story preferences in fiction and my views of what time travel or multiverse theory would actually say about free will in reality. After all, the main reason I’m not crazy about time travel as a genre is because it usually doesn’t obey anything remotely similar to realistic physics, or even hold together logically by its own internal rules.

As for free will, yes, it’s a relevant question if it exists, but my point is, you can’t take the restrictions on a time traveler’s free will as proof that nobody has free will, because a time traveler is operating under a radically different set of conditions and constraints from an ordinary person, so their situation can’t be generalized to others.

@41/CLB:

Cleverly phrased to be unfalsifiable, well done! :-) I respectfully suggest that if you can find essentially no acceptable stories, the issue may not be the writers but that you’ve set a ridiculously high bar for acceptance. Your prerogative, of course.

You have proffered ‘story logic’ as your primary objection, but the explanations strike me as post-hoc rationalization of personal taste. However, they prompt a question: are the (few) time travel stories you do like weighted towards those involving stable time loops? Those seem to be requirements of most legitimate time-travel solutions from real-world physics, and such worldlines seem to be inherently less prone to continuity problems. A key to their use in fiction seems to be to avoid the possibility of ‘meeting yourself’ or ‘changing the past’, which the better-written stories tend to do. The conundrum of an event being its own cause remains, but that’s more of a metaphysical issue than one of physics, and seems like it should require a lower bar for acceptance than some of the legitimate issues associated with a time-reset loop.

@50/Ian: Good grief, there’s no call to attack me. I’m not asserting any kind of factual claim, and I’m not saying that you can’t like the genre. I’m just answering the question of why I personally don’t love time travel as a genre, and I’m entitled to that opinion. I never claimed it was anything but personal taste. So lay the hell off. You’re totally out of line here.

@51: Apologies, no offense intended. I do respect your opinions even if we disagree. I honestly felt the nuances of your view of the issue could prompt an interesting discussion of the difference between time-reset and stable time loops, and whether SFF tends to handle one type better than the other.

This discussion seems to be getting unnecessarily heated. Please review the commenting guidelines–particularly the bits about not taking/making arguments or differences of opinion personally–and keep your responses civil and constructive in tone.

princessroxana @45: I was going to throw Primer in there to complicate the physics a bit, but I think they are already managing that by themselves…

Personally, I have a soft spot for the Dark Matter time loop episode ‘All the Time in the World’, purely for the comedy value.

Has anyone here read Elan Mastai’s All Our Wrong Todays? I’d put it near the top on my personal list of time travel stories. Very well done.

The twist is that the traveler starts out in a utopia, kind of analogous to what if the Jetsons had become real by now; flying cars, clean environment, plenty for all… that type of world. Going back in time and altering an event results in creating essentially our contemporary world, decidedly not a utopia.

The time travel is essentially created when a device that promises free unlimited energy is brought online, creating a radiation signature that can be followed back in time and space to that genesis moment. The space component dealt with something frequently overlooked in time travel stories. You don’t just travel in time. Since the planet has moved in its orbit, you need to travel to the prior location in space. Doctor Who deals with this by calling the ship Time And Relative Dimensions In Space. Many stories just use a dial or clock that winds back.

There’s also a more terrifying method of traveling forward in time that involves stasis, while you remain consciously aware.

@55 Sunspear I really enjoyed it. The forward travel in time was bonkers. I don’t think anybody born after the popularization of the Internet and smartphones could survive it with sanity intact haha

I’m not sure I would call it a time loop in the sense of this article though, that would require more repetitions. AOLT is more like a classic time travel story to me (like some of the Stainless Steel Rat stories, or All You Zombies).

@55/Sunspear: The tendency of time-travel stories to ignore the motion of the Earth is one of those recurring logic holes that annoy me about the genre. And it’s one that goes all the way back to H.G. Wells, although at least Wells portrayed his Time Machine as passing through all the intervening moments at an accelerated rate — although people around the machine were unaware of its presence, a paradox that never quite made sense (yet another logic hole!). I mean, if it were just sitting in place the whole time, people would see it there and perceive the guy inside as slowed down to the same degree that he saw them as sped up.

Devin @12-

I see you and raise you “Roswell that Ends Well”.

@58, more bootstrap paradox than time loop that, something they would do again in Bender’s Big Score, but well picked nonetheless.

@59/Devin: Yeah — there’s a recurring problem here that people are interpreting “time loop” in two different ways, as a single self-consistent loop that causes itself (a la 12 Monkeys, the movie) and as an endlessly repeating loop that the main character is trapped in and must escape (a la Groundhog Day). This column was specifically about Groundhog Day-type loops, but people keep bringing in 12 Monkeys-style loops, which are a very different thing despite the shared name. A 12 Monkeys “loop” is continuous — the time traveler’s actions in the past turn out to be what created their timeline in the first place, creating a closed path. A Groundhog Day “loop” is discontinuous — time moves forward and jumps back like a stuck phonograph needle jumping a groove, and the time traveler’s actions change the details of each loop but fail to change the one thing that will break them out of the loop, until they finally figure it out at the end of the story. It’s confusing that two completely different types of time travel story are popularly known by the same name.

The issue gets further muddied because many well-known stories involving time travel—e.g. Babylon 5, Harry Potter, arguably most of Doctor Who—don’t really involve either flavor of repetitive ‘looping’ at all: the characters’ personal timelines move inorexably forward, it’s simply that their worldlines are bent in such a way to allow observing or interacting with events they had previously believed to be in their (subjective) pasts or futures.

If I recall correctly, Quantum Leap on at least one occasion explained its time-travel theory as scrunching up the leaper’s timeline like a string whose ‘loops’ then touched each other at various points and allowed the crossovers. Might that, along with other fiction inspired by the show’s popularity, have contributed to the use of ‘looping’ to describe anything involving back-and-forth time travel?

@61/Ian: I don’t think Quantum Leap was really remembered for its time-travel “theories” per se, such as they were. It was a fantasy show that put only the most cursory effort into its pseudoscience handwaves. (The bit about “neurons and mesons in the brain” always drove me crazy. Mesons are subatomic particles, not cells!!!) So I doubt it popularized any specific terminology.

The term “loop” is generally used to refer to something recursive, i.e. something that cycles back on itself. A typical time travel story isn’t recursive because the time travel changes things and puts history on a different path. It’s just that the two kinds of “time loop” stories are recursive/cyclical in different ways — one is a single closed path that causes itself, so that its end is its beginning, and the other is a repeating sequence of events, so that it keeps jumping back to its beginning despite every effort to change it. Conceptually, they have similarities, but as stories, they unfold in very different ways and serve very different narrative and dramatic purposes.