As literary chimeras go, John Wray could be called a blend of all sorts of authors. Aspects of his novel Lowboy read as though Dickens teleported Oliver Twist from the 19th century onto a contemporary subway train. But, Wray is also a history junkie with an eye towards science fiction. Though his novel The Right Hand of Sleep isn’t science fiction, its title is a reference to The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin, one of Wray’s idols.

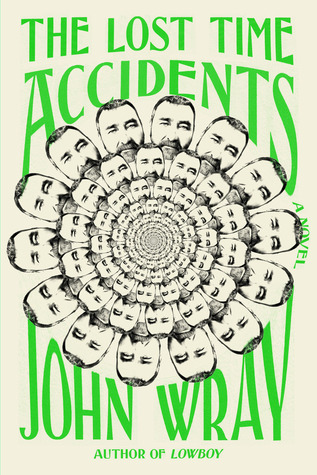

With his latest novel—The Lost Time Accidents—John Wray presents his unique cocktail of historical fiction blended with the science fiction tradition of time-slipping. For a writer who isn’t really writing science fiction, John Wray sure knows a lot about science fiction. I chatted with him recently about the inspirations for his latest book, how to write a multi-dimensional family saga and what Ursula K. Le Guin taught him about imitating old school SF writers.

Ryan Britt: How much did other time-slipping SF novels influence the writing of this novel? (i.e. Dick’s Martian Time-Slip, Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, et al.?)

John Wray: I think it’s safe to say that this crazy book was influenced by each of the many odd and idiosyncratic and glorious SF novels and story collections that had such a profound effect on me between the ages of about fourteen and the present moment. (Hopefully the influence of the many terrible and lazy examples of the art that I dug up will be more modest.) Philip K. Dick looms large, of course, as he does in the work of so many people, both in SF and in the so-called mainstream. The Lost Time Accidents takes human subjectivity and psychological aberration as one of its major themes, come to think of it, so the debt to Martian Time-Slip and A Scanner Darkly, etc is probably even greater. Vonnegut was a guiding light to me as well, of course, both for his humor and his virtuosic straddling of genres. And too many others to name or even count: Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven, Niven’s Ringworld series, Theodore Sturgeon, C.S. Lewis, P.D. Ouspensky, Gene Wolfe, Stanislaw Lem…the list would stretch all the way back to Childhood’s End, the first SF novel I read, back in November of 1983. From that moment on, I was doomed.

Britt: There’s various “original sources,” in the form of fictional diaries and journal entries. This reminds me a little of nested-narratives like Frankenstein, where a letter to someone’s sister can faux-innocently encompass a whole narrative. Why was this device essential for The Lost Time Accidents?

Wray: For some reason it was important to me that the narrative feature not just an ‘I’, but a ‘you’—a specific person the narrator is addressing, at the same time that he addresses the book’s actual reader, whoever he or she may be. I wanted that feeling of urgency, of focus, of desperate life-or-death appeal. Waldy Tolliver is writing this account of his family’s misadventures in the timestream for a definite reason—to reveal his most sinister secrets to the woman he loves, to shock her and entertain her, in the hope of somehow bringing her back to him. Our narrator and hero here isn’t some idle, self-indulgent diarist. He’s a writer on a mission.

Britt: Talk to me a little about the historical influences. Or to put it another way: do books involving time-travel (or time-slipping) need to do their historical homework?

Wray: I think that depends entirely on the writer’s agenda—on the purpose that time-travel serves in the narrative. Is the book in question a sober, naturalistic, Arthur C. Clarke-ish investigation of what travel through time might realistically entail, or is movement through time serving a metaphorical purpose, as it did for H.G. Wells? Wells was most interested in writing about the future in The Time Machine, and even then primarily in an allegorical sense, as a means of describing the evils he saw in the present. The Lost Time Accidents, for me, falls somewhere between those two poles—the novel’s fantastic elements derive their power and their meaning from their relevance to our hero’s daily life. When the story touches on the rise of cults in America in the sixties and seventies, or the Manhattan Project, or the shock Einstein’s theories caused at the start of the 20th Century, it was paramount that I had done my homework. The Man In The High Castle would have been a disaster if Dick hadn’t been a WW2 buff.

Britt: One of the plot-driving engines in The Lost Time Accidents is the righteous indignation that gets passed down through generations of the Toula/Tolliver line. As family lore would have it, if Albert Einstein hadn’t stolen the spotlight with his half-baked theory of relativity, the Toula brothers’ own theories of time and space would have garnered the acclaim and attention that Einstein received. (To add to the comic effect, Einstein is never mentioned by name—he is contemptuously referred to as “the Patent Clerk” throughout.) Were there any particular historical cases of scientific rivalry that got you thinking about this element of the story?

Wray: I’ve always been intrigued by the story of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, the famous French zoologist and theorist, whose contributions to our understanding of the natural world, which were immense, were completely overshadowed by Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Lamarck got so much right—he was a titan of science—but now, if we learn about him at all, his errors are all we hear about: above all, his notion that the traits an animal acquires in its lifetime can be passed on to its offspring. Science is a tremendously creative field of human endeavor, of course, and when I began doing my own research for The Lost Time Accidents, I had the idea to consider science as one might consider literature: a rich field of parallel narratives, competing but not mutually exclusive, each of which might display its own very subjective type of elegance and beauty.

Britt: What was the zero hour of this project for you? Was it wanting to write a multigenerational family saga, was it this bizarre psychological theory of time travel, or something else altogether?

Wray: Of all my books thus far, this one had the strangest beginning. It began with the title. A decade and a half ago, I wrote my first book under slightly absurd circumstances: in order to be able to afford to write full-time and live in New York City with no real income, I squatted, essentially, in a band rehearsal space in the basement of a warehouse under the Manhattan Bridge. There happened to be a back alcove that I pitched a tent in, and I lived in that tent for a year and a half. I had a very strange sleeping and waking schedule, in part because I was living underground. There was no light, to phone, no heat to speak of. I bathed at friend’s apartments or in the bathroom of the Brooklyn Heights Public Library. I was more cut off from the rest of the world than I’d ever been before,and certainly more so than I’ve been since.

I would often wander, late at night, around the neighborhoods of Dumbo and Vinegar Hill and Brooklyn Heights, and sometimes much farther. One of those nights, I turned a corner and caught my first glimpse of the Hudson Power Generating Station, which is an enormous old electrical station by the river. There was this wonderful flickering sign above its gate which read “Welcome to Hudson Power Generating Station,” and below that was a blank space where numbers were supposed to go, followed by “00000 Hours Without A Lost Time Accident.” And I remember thinking, “I have no idea what that terms means, but it’s a fascinating phrase.” It had a magic for me, right away—those words just seemed so resonant and mysterious. As I began to write the book, those words became something like a chip from the Rosetta Stone for me: the multitude of valences and possible meanings gave rise to the various strands of the narrative. The novel became, in a way, a mystery story, in which the central mystery is not “Who did it?” but “What was done?”—in other words, what could this fragment of a scientific theory, found scribbled in a long-dead physicist’s notebook, ultimately turn out to mean? Could the answer, as our narrator believes, change the way the human race relates to time itself?

Britt: Did you have a specific model for the novel’s hilariously third-rate SF hack and so-called ‘StarPorn’ originator, Orson Tolliver?

Wray: I had quite a few writers in mind when conceiving of Orson. Not so much for the samples of his writing that pop up here and there in the book—I can write terribly all by myself!—but for the ups and downs of his curious and star-crossed career. An obvious point of reference, of course, was L. Ron Hubbard: like Hubbard, Orson Tolliver writes a book that gives rise to a bona-fide, real world religion; though in poor Orson’s case, unlike Hubbard’s, it happens by accident, and he feels nothing but horror at the monster he’s created. And I was certainly thinking of Philip K. Dick when writing about my character’s extraordinary output of stories and novels. I even mention Dick at one point, in this context–I say that Orson was writing at a greater clip than even Philip K. Dick, at his most amphetamine-fueled, was able to muster. But of course the field has always been known for its hyperproductivity.

I was also very fortunate, during the period when I was writing the first draft, to spend some time with Ursula K. Le Guin, whom I interviewed for The Paris Review. She told me a lot of anecdotes about what it was like to write as part of that extended SF community in those amazingly fertile and adventurous decades, the 60s and 70s. That was an incredible resource and of course just a great thrill and joy.

Britt: At one point, the novel’s great villain, The Black Timekeeper, seems to be espousing a theory that reads almost like an anti-Semitic variation of what Philip K. Dick is exploring in VALIS.

Wray: VALIS was certainly a touchstone, yes.There’s a lot of play like that throughout the book: references to writers I admire and riffs on books that were important to me at different times in my life. What’s more, in the course of the many years I spent working on the project, I came to realize that I’m far from the only writer to keep himself (and hopefully the close reader) entertained with games of that nature. It was the strangest coincidence–a few months after I wrote the chapter of The Lost Time Accidents in which our hero is attempting to get into the power station and these various gates—that hidden tribute to Kafka’s “Before the Law”—I watched Martin Scorsese’s After Hours for the first time. In After Hours, Scorsese inserted a secret homage to that very story. Griffin Dunne’s character is trying to get into a late-night after hours club somewhere on the Lower East Side, and he has a conversation with the bouncer at the club, lifted almost word for word from Kafka’s story. Very rarely has Scorsese made the kind of movies that allow for that sort of conceptual play, but in the case of After Hours, he did. “Before The Law” one of the greatest stories in literature, so perhaps I shouldn’t have been so surprised.

Britt: You’ve said in interviews that you did a lot of the writing of your last novel, Lowboy, while riding the subway—just as the protagonist himself does for a large stretch of that book. Was the process similar for The Lost Time Accidents, or did you write this in a very different environment?

Wray: In this book, a sensory deprivation chamber plays a pivotal role:the so-called “exclusion bin,” invented by our hero’s reclusive maiden aunts, that may or may not function as a time machine. I created a series of exclusion bins for myself while I was writing the really difficult parts of the story, including, at one point, a roughly casket-sized box that was lightproofed and soundproofed in a similar way to the contraption Waldy’s aunts placed him in as a sort of human equivalent to Laika, the cosmonaut dog of the Soviet space program. It wasn’t always necessary, but it was helpful at certain times. And it was surprisingly fun to shut myself away in. One of these days I might go in and never come out.

Ryan Britt is the author of Luke Skywalker Can’t Read and Other Geeky Truths (2015 Plume/Penguin Random House) His writing has appeared on Tor.com since 2010 both as a staff writer and ongoing as an irregular contributor. Ryan began the column Genre in the Mainstream in 2011 on Tor.com as a place to talk about the intersections in publishing between conventional literature and SF. In addition to Tor.com, Ryan’s writing appears regularly with VICE, BN Sci-Fi, and Electric Literature. He is a staff writer for Inverse and lives in New York City.