Holiday horror has a long and illustrious history, from traditional Victorian Christmas ghost stories like Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843) to more contemporary examples like Black Christmas (1974), Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984), Krampus (2015), and A Christmas Horror Story (2015), among others.

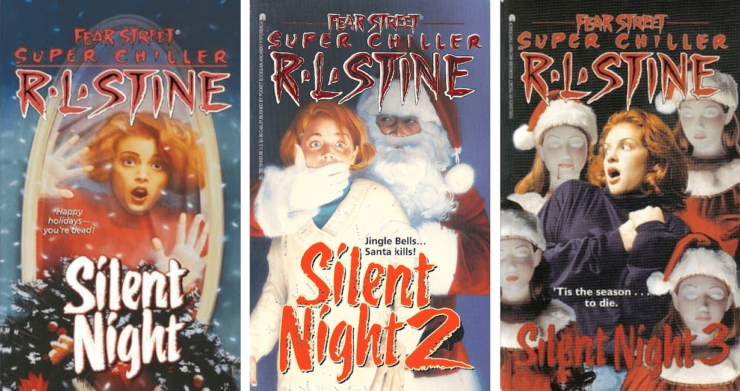

R.L. Stine’s first Silent Night (1991) Fear Street novel combines the traditions of the Christmas slasher film with the redemptive transformation of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, with mean girl Reva Dalby as the Scrooge character in this variation.

Reva is a spoiled rich girl whose dad owns the Dalby’s department store chain, with its flagship store in Shadyside. Reva’s dad makes her work at the store over the holidays, where she exhibits what may be the worst customer service ever: she ignores, heckles, and abuses potential customers, and never makes a single sale. She manipulates the boys in her life, stealing other girls’ boyfriends and then dropping them as soon as she gets bored, and she frequently demeans and dismisses her cousin Pam because Pam’s family is poor. She hires some of her classmates for seasonal help at the store and humiliates them just for her own entertainment, telling Lissa to show up in her fanciest clothes for a special job when the she’ll really be working in the stockroom and instructing Robb to wear a suit because she has a special public relations-type job for him, when she has him set to play Santa Claus because “he’s so roly-poly, he wouldn’t even need any padding!” All in all, it’s not that surprising that someone might want to murder Reva.

In Silent Night, Reva is the target of a range of mean pranks, including someone putting a needle in her lipstick, sending her a perfume bottle filled with blood that spills all over her, and delivering a box with a mannequin posed to look like a dead body. However, the next box Reva receives has an actual dead body in it. Reva is almost murdered in the dark, deserted store after hours, when she catches the murderer attempting to break into her father’s safe. Reva ducks at the last moment and watches as her attacker is electrocuted by the store’s massive Christmas tree.

In the aftermath of her near-death experience, Reva has a change of heart:

‘If I hadn’t been so cold, so bottled up, so hateful, maybe none of this would have happened … I have real feelings now’, she realized. ‘Warm feelings. Sad feelings …’ Silently she made a New Year’s resolution to herself to never lose those feelings again.

This self-reflection makes some sense, but ultimately, the murderer is a disgruntled former employee that her father had fired, whose revenge scheme is complicated by attempted burglary and really has nothing to do with Reva at all, belying her newfound sense of self-awareness and reaffirming her narcissistic belief that the whole world and everything that happens in it—or at least in Dalby’s department store—revolves around her. Nonetheless, the final pages of Silent Night are cautiously optimistic.

Buy the Book

Echo

This optimism is misplaced, however, and in Stine’s Silent Night 2 (1993) and Silent Night 3 (1996), readers see the same old Reva, back to demeaning, dismissing, and abusing anyone who isn’t useful to her.

The only relationship in the trilogy that challenges Reva’s awfulness is the bond she has with her younger brother Michael. Their father is a bit of a workaholic and their mother died a few years before the action of the first book (a loss that Reva uses to excuse all sorts of bad behavior on her part). Reva’s relationship with her brother is alternately affectionate and dismissive: for example, in Silent Night, she promises to take him to see Santa Claus at Dalby’s, but continually flakes on him and can’t understand why he’s upset by her constant refusals. However, when they finally make it to see Santa, Reva seems genuinely moved by Michael’s excitement and joy.

Michael is also a sort of proxy for Reva’s own trauma response (or lack thereof), as she refuses to confront or effectively deal with the emotional and psychological effect of her experiences. Michael is altogether absent from Silent Night 2, jumping at the chance to go on a Caribbean vacation with his friend’s family and ignore the horrors of Christmas Past altogether. With his return in Silent Night 3, Michael is having some behavioral issues and pretending he is an avenging superhero, jumping out and attacking people at random times and actually saving Reva’s life (albeit accidentally) with his over-the-top antics when he pounces on the person who is attempting to murder her. As Reva explains Michael’s behavior to her friend, “Michael has been acting out these violent scenes lately…Dad thinks it’s because of my kidnapping,” reflecting an emotional engagement and response on Michael’s part that Reva herself never quite manages.

Silent Night 3 ends with a shaky and insubstantial suggestion of some personal growth on Reva’s part. First, Reva hears the song “Silent Night” on the radio—which was playing the night she was attacked in the deserted store in the first novel and has haunted her dreams ever since—and doesn’t turn it off, telling herself “You can’t let a Christmas song give you nightmares anymore.” The second potential indicator of personal growth in this final scene is that she is kind to her cousin Pam, complimenting Pam on her beautiful handmade scarves, and thrilled to be receiving one as a Christmas gift. This is a pretty low bar for personal growth and given the larger narrative scope of the trilogy, doesn’t seem likely to be a lasting change anyway, a lump of coal in the series’ final pages.

A predominant theme that resonates through all three of Stine’s Silent Night novels is class disparity, along with the rampant consumerism and economic pressures of the holiday season. Throughout the entirety of Stine’s Fear Street series, Shadyside is depicted through a stark contrast of haves and have-nots, with the dominant responses of the wealthier residents ranging from obliviousness to ambivalence and cold disinterest. This representation of class difference encompasses both teen characters’ home lives (parents who struggle to find work, the teens working to help support their families) and the teens’ interactions with one another in a strict system of high school stratification, where the wealthy and the working-class rarely mix.

While the impact of class and economic position are identified and at times, even presented as a notable element of characterization or motivation, Stine never addresses this inequity in any substantial way, and the wealthy characters never gain a new perspective or work to make anyone else’s lives better. In the Silent Night trilogy, several of the young adult characters are grateful for the chance to work at Dalby’s over the holidays so that they can help cover basic family needs like food and heat, as well as to provide their families with a good Christmas, while the characters who are driven to commit crimes like burglary and kidnapping do so out of desperation rather than greed. In the end, neither of these paths—working at the department store or risky criminal schemes—pay off for anyone, with the status quo firmly reinforced at the end of each novel, and the demarcations between Reva’s wealth and other characters’ poverty remain unchallenged. While Stine doesn’t represent these working-class characters as bad or evil, they are shown as lacking agency and largely pitiable, which shapes how they’re treated by other characters within the books and surely impacted teen readers’ perceptions of class difference in the real world and their own interactions with peers, as perhaps unfortunate but a problem beyond their ability to address, alleviate, or fix.

Reva’s cousin Pam, in particular, is willing to do anything to get out of her current economic circumstances: she’s the getaway driver for a separate burglary scheme in Silent Night, works in the stationary department at Dalby’s in Silent Night 2, and becomes a designer in Silent Night 3. This last option seems the most promising and most likely to pay off, suggesting that in breaking the cycle of poverty, forging your own path is the only way to succeed. That trailblazing comes at great personal cost and financial risk however, as Pam invests a significant amount of time and money that she doesn’t have to spare into this venture. Pam is the most interesting and complex character in the trilogy, growing and changing, making mistakes, and discovering who she is, though her character arc remains marginalized by Stine’s central focus on Reva. Over the course of these three novels, Pam agrees to be a getaway driver but is too much of a rule-follower to really commit any crimes, she sets Reva up to be kidnapped after Pam’s own accidental abduction (they mistake her for Reva), she sells her cousin out to the kidnappers in a bid for her own freedom, and she saves Reva’s life by tackling (yet another) attempted murderer. In the end, Pam finds her passion and sense of self, and is able to chase her dreams, fight for what she wants, and not care what Reva thinks about any of it. While Reva is the narrative engine of the Silent Night trilogy, Pam is its heart and the fact that her story gets shunted aside for repeated variations of Reva’s narcissism and cruelty is disappointing.

Beyond the troubling representations of class difference that run throughout these books, Silent Night 3 is unquestionably the most problematic novel of the trilogy. When Reva returns home to Shadyside over her winter break from college, she brings her roommate Grace Morton. Grace is, in many ways, an anti-Reva. Like most of the other characters in these books, Grace is of a lower social and economic position than Reva, who sees inviting Grace home as a tremendous favor. Grace is largely incapable of standing up to Reva, is scared of her own shadow, and endures Reva’s dismissive insults and poor treatment with zero objection. The main reason Grace has come to spend the holidays with Reva’s family is because she’s afraid to go home, where she might run into her abusive ex-boyfriend Rory, who is threatening to kill her. Grace gets several threatening phone calls while she’s at Reva’s house and is on edge, flinching at every loud noise. Instead of being empathetic and supportive, Reva has no patience with Grace’s terror, calling her a “wimp” when Grace shows up with a black eye and refuses to let Reva call the police or an ambulance. Reva later dismisses the attack and its aftermath as simply “unpleasant” and considers Grace with “a mixture of curiosity and distaste,” a horrific response that combines victim-blaming and prurient voyeurism. Reva goes back and forth between seeing Grace’s trauma as exciting or annoying, with no concern at all for her friend’s safety, well-being, or emotional turmoil.

This representation of relationship violence and Reva’s unconscionable response to her friend’s suffering are bad enough, but it becomes even worse when Grace herself becomes monstrous: Rory is actually dead, killed in an accident for which Grace herself was responsible, and was a kind and supportive boyfriend. Grace is hallucinating these threatening interactions with Rory, recasting him as a figure of fear and danger as a way to assuage her own guilt, and Grace herself is responsible for the rash of murders at Dalby’s department store during Silent Night 3‘s holiday season. While this representation is sensationalized and entirely unrealistic, it gives readers a narrative pattern in which someone might lie about experiencing relationship abuse and can be doubted, questioned, or ignored, because they might be mentally unstable or even potentially dangerous. Much like Christopher Pike’s tale of a woman who lies about being raped by a famous man and then blackmails him in “The Fan From Hell,” Stine’s Silent Night 3 presents a narrative that casts doubt upon and could potentially silence victims of relationship violence in the real world. Stine’s Silent Night books combine holiday horror with troubling representations of adolescent difference, from economic struggles to abuse, in a way that makes this difference a spectacle rather than a call to action or a problem to be addressed in any meaningful way.

Throughout all three Silent Night books, people keep dying at Dalby’s, with corpses interspersed with the holiday decorations and the latest hot sale items. And really, shouldn’t multiple homicides at the same department store every Christmas season inspire significant horror or, at the very least, a drop in sales? It’s a weird holiday tradition for Shadysiders and Dalby’s shoppers to be okay with, but that seems to be the case. While Reva is originally presented as a Scrooge-type character on the path of redemption, she keeps taking detours into self-serving manipulation and casual cruelty to everyone around her, and any personal growth or self-actualization on Reva’s part remains unrealized. At the end of Silent Night 3, Reva is a sophomore in college and has effectively surpassed the usual age of Stine’s adolescent protagonists and readers. While Reva would hopefully continue to grow and change beyond the trilogy’s final pages, this isn’t a story Stine’s readers will hear, leaving them with the not so “happily ever after” of an unrepentantly spoiled and abusive Reva, exploitative class disparities still firmly in place, and an incredibly damaging representation of relationship violence and mental illness. Bah, humbug.

Originally published January 2022

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.