Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

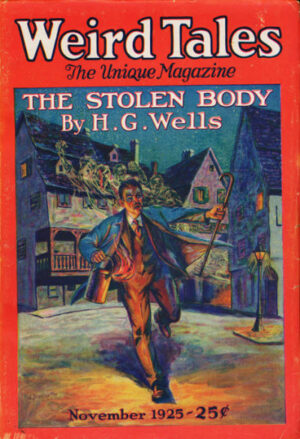

This week, we cover H. G. Wells’s “The Stolen Body,” first published in The Strand in November 1898, and notably reprinted in Weird Tales (celebrating its centennial this year!) in November 1925. Spoilers ahead!

“And as he went past me,” said the porter, “he laughed–a sort of gasping laugh, with his mouth open and his eyes glaring–I tell you, sir, he fair scared me!”

In addition to his day job as senior partner of Bessel, Hart and Brown, Mr. Bessel is well known in psychical research circles as “a liberal-minded and conscientious investigator.” His interests are thought transference and apparitions of the living. In November 1896, he and fellow enthusiast Mr. Vincey begin testing the possibility of projecting an apparition through space between their London homes.

At pre-arranged times, Bessel shuts himself up in his rooms at the Albany, Vincey in his at Staple Inn. Bessel self-hypnotizes himself and then, through resolute focus on his friend and sheer force of will, attempts to project his phantom-self the two miles to Vincey’s apartment. During the fifth or sixth session Vincey sees Bessel standing before him, face pale and anxious. The apparition looks over its shoulder and vanishes.

Buy the Book

Camp Damascus

Vincey hurries to the Albany to confirm their success, but Bessel’s not home. His door is open, his rooms vandalized by someone intent on random destruction rather than theft. The porter says that the mess “settles it”: Bessel’s gone mad. Earlier, a hatless and disheveled Bessel rushed out of the Albany, passing the astonished porter with a queer laugh, crying out, “LIFE!”

Vincey returns home in perplexity. Falling asleep at last, he dreams of Bessel, face contorted with terror, calling for his help. He wakes convinced Bessel is “in overwhelming distress.” He starts back toward the Albany, but “some unaccountable impulse” steers him toward the nocturnal bustle of Covent Garden. Bessel appears, wild-looking and wielding a walking stick. He shows no sign of recognizing Vincey nor his own name. Instead he savagely strikes Vincey across the face. A crowd of shouting police and civilians pursues Bessel out of sight. Bystanders tell Vincey that Bessel barged into Covent market screaming “LIFE! LIFE!” and attacking people at random.

Back home, Vincey nurses his wounded face and sits vigil, awake in hopes of avoiding another nightmare. Through the night he feels “a curious persuasion” that Bessel’s trying to talk to him. In the morning, he goes to Bessel’s office and talks to his partner. Mr. Hart also had a vision of a distressed Bessel. The two go to Scotland Yard. They learn that Bessel’s still at large after an hours-long rampage of vandalism and violence, including “an atrocious assault upon a woman.” He disappeared around 2 A.M. and hasn’t been sighted since.

All that day Vincey senses Bessel trying to contact him. That night he dreams of an anguished Bessel pursued by “other faces, vague but malignant.” The next day he visits the house where celebrated medium Mrs. Bullock is staying. As soon as her host Dr. Paget hears the name “Bessel,” he reveals that, at a seance the evening before, Bullock received this message through automatic writing: “George Bessel… trial excavn… Baker Street… help… starvation.”

This message leads searchers to find Bessel at the bottom of a shaft abandoned during construction of a new electric railway. He’s broken two ribs, an arm, and a leg, but his madness has passed. Rescuers take him to the house of a nearby physician, where on the second day of treatment he volunteers a statement which remains consistent through many repetitions, including to the story’s unnamed writer:

During his last session with Vincey, Bessel finally achieved psychic separation from his body. He stood beside it as a cloudlike “greater self” that looked down on all of London and its occupants, even interior spaces. It was “like watching the affairs of a glass hive.” He believed he’d entered a sphere of existence beyond humanity’s. He struggled free from his “earthly carcass” so he could travel freely in this new world. He sought out Vincey as planned, but could only contact him by probing his brain with immaterial “fingers” to the pineal eye. Vincey started, finally seeing Bessel. That instant, Bessel became aware that the vapors around him were voiceless entities with faces of “gaseous tenuity.” Their “evil, greedy eyes were full of a covetous curiosity.” Their “vague hands clutched at” him. “Idiot phantoms, they seemed… beings unborn and forbidden the boon of being… craving for life.”

A second probing of Vincey’s pineal gland brought a dire consequence. A “great wind” blew Bessel from his earthly body. He returned too late: One of the vapor-entities had entered his “carcass.” Finally alive and incarnate, it capered with heedless, destructive glee through his rooms, then escaped into the city. For twenty hours the “evil spirit” would possess Bessel’s form, leaving him to struggle with only intermittent success to reach his friends. He feared that if his body’s “furious tenant” should kill it, he’d be stranded forever in the beyond, like the dim human forms with sad faces that he’s seen in the beyond-space along with the life-craving phantoms.

Bessel’s salvation came when he chanced on a crowd of malignant spirits and lost humans hovering over an earthly seance. They were all trying to reach the medium and communicate through her; Bessel did the same. An anxious side-trip back to the doings of his usurper revealed its fall into the Baker street shaft! Desperate, Bessel broke through to the medium and left the message that Dr. Paget would give Vincey. Meanwhile Bessel watched over the suffering rage of the usurper. At last weary of its “lesson of pain,” the entity deserted its stolen body. Bessel reclaimed it, to suffer until his rescue three hours later.

In spite of that suffering, Bessel’s “heart was full of gladness to know that he was nevertheless back once more in the kindly world of men.”

What’s Cyclopean: Bessel’s cloud-ish astral body sways, contracts, expands, coils, and writhes. And feels “temerarious excitement” about his new experiences… until he finds himself surrounded by evil faces with “mouths that seemed to gibber”!

The Degenerate Dutch: We don’t learn the details of the “atrocious assault upon a woman,” but the implications are strong.

Weirdbuilding: Wells joins and contributes to a long line of body-snatchers and body-switchers, from Jekyll and Hyde to Yith and possessing demons.

Madness Takes Its Toll: “Madness,” it turns out, results from one’s body being taken over by a demon from the silent, envious world beside our own. Huh. Interesting.

Anne’s Commentary

The Strand Magazine debuted Wells’s “Stolen Body” in 1898. Weird Tales reprinted it in 1925; the illustration of “Body” is one of the magazine’s most sedate covers, eschewing leering villains, damsels in deshabille, and menacing monsters for a mere English gentleman on a quaint London street, wielding a walking stick and oil can at nothing in particular. What, no leering gentleman looming over a lady with torn bodice, while malicious spirits cheer him on?

Many real-life paranormal investigators go their whole lives without running into worse difficulties than toes stubbed in insufficiently-lit haunted houses or bank account-draining purchases of artifacts with MADE IN CHINA filed off their pedestal bottoms. Such investigators rarely make it into weird fiction, unless as a comic aside—Mrs. Montague from Jackson’s Hill House comes to mind, and some of Benson’s bumbling psychic sleuths, like the eponymous hero of “Mr. Tilly’s Seance.” Wells himself created the most hilarious (yet truly brilliant) investigator in Food of the Gods’ Mr. Bensington. Bensington, however, gets himself and all that his Food touches in literally BIG trouble, and he does it in the classic manner: Defying conservative peers and public, he dares to LEARN WHAT MAN WAS NOT MEANT TO KNOW and DO WHAT MAN WAS NOT MEANT TO DO.

For some, playing around with living apparitions and thought transference might be STEPS TOO FAR. I wouldn’t rate these pursuits up there with the mysteries of death and the afterlife, or with attempting to access other dimensions, as Lovecraft’s investigators often do. Take “From Beyond’s” Crawford Tillinghast, who penetrates other planes via his pineal gland-stimulating resonator—there’s that pineal “eye” again! Maybe the inhabitants of other spheres are benevolent, or at least neutral, but don’t bet your life on it, or the fate of our world either.

Mr. Bessel is no dilettante. He’s well-regarded by the “psychical research” community and has no overweening ambitions of conquering the Grim Reaper or enlisting other-dimensional entities in world conquest. But—you can’t know what you don’t know. The platitudes of a joyous spirit realm generally obtained by mediums of his day don’t prepare him for the malignant beings and tragic lost humans he meets when he crosses over—the former make Mantel’s Aldershot fiends look merely mischievous. These cloudy presences might be content with their lot if their world and ours didn’t press so closely on each other. They’re eternally observing earth’s LIFE in all its tantalizing variety, and battering themselves against the glass-like but impenetrable barrier between them and their desires.

Impenetrable, that is, unless some feckless human opens a door. The genuine medium Mrs. Bullock opens pinholes to beyond; even that’s enough for spirits to overwhelm her “switchboard.” Ignorant of the consequences of messing with pineal-eyes, Bessel pops a momentary between-worlds portal. That’s all a wraith needs to slip through into a conveniently empty body, while Bessel pops his astral self, mind and soul, into Wraith-land.

Say what you like about how bad the Yith are; at least when they steal your body, they provide you with another. So it’s not a great exchange if you end up in some doomed species abandoned by a mass Yith-migration. Or if you’re not scholarly enough to welcome a sabbatical where you have nothing to do but write your magnum opus. The Yith, however, go big for academics—built-in library access!

Bessel’s exchange doesn’t have time to read. It’s busy rampaging through London like a souped-up Jekyll in Hyde. Maybe wraith-human exchanges can account for otherwise inexplicable outbursts of madness and criminal behavior. Maybe, if a wraith avoids killing its host body, it can draw on its experience of observing humanity and become a long-term menace. Or a long-term inmate of an asylum or prison.

Here’s my big quibble with this story. The body-thief’s offenses range from major vandalism to the infliction of serious injury (including on policemen), and culminating with the “atrocious assault” on a woman, probably Wells’s euphemism for rape. Yet Bessel suffers no legal consequences for his body’s crimes. Recovered from the Baker Street shaft, he’s taken not to jail but to a neighboring physician’s house. Nor does he end up under the care of alienists or, shown to be of compos mentis, under the watch of prison guards. Do the authorities just accept his claim that an evil other-dimensional spirit stole his body and was responsible for its subsequent depredations? The devil made him do it all—he was possessed, not himself, innocent!

I don’t think the authorities would be credulous enough of paranormal alibis to let Bessel off completely. He’s a first-time offender of high social status, but still. The likely explanation is a narrative one. Wells has told the story he wanted to tell and doesn’t want to dilute it with a coda about trials and lawsuits, incarcerations, the indignations of press and public.

Thus protected by his author, Mr. Bessel might well count himself lucky to be “back once more in the kindly world of men.”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

A particular sort of narrative voice has gone out of style somewhere in the last hundred years: a careful, clinical report of weird and terrifying events meant to make them seem weirder and more terrifying because it’s the voice of credibility. Perhaps it’s the third party to whom events are being reported, or the investigator/journalist/doctor reconstructing story-shards from multiple witnesses, or the actual protagonist trying desperately to make someone, anyone, believe them.

Depending on my mood and how close the narrator is to the actual events, I can find that voice exasperatingly distant or as delightfully tropey as unreasonably informative bas reliefs. “The Stolen Body” falls somewhere in the middle. I enjoy examining all the pieces, circling around to the core of what Bessel saw; I don’t see why we need to be at the remove of the investigator who spoke to the people who actually did things around the actual possessed person. C’mon Herbert, I know you can do a more impressive journalistic voice!

And then on the other other hand, the more removed voice provides the opportunity for gems like the attempt to involve “a well-known private detective” who “accomplished nothing in this case,” and so “we need not enlarge upon his proceedings.” Perhaps a detective who lives on Baker Street, near where Bessel is ultimately retrieved? Whose first appearance predates this story in The Strand by just 11 years? Whose author is known to prefer consulting mediums over attending to logic and science?

And, too, the clinical voice really does make some moments of high emotion and acute observation stand out. The crowd “greedy” to see Bessel’s injury and offer advice and become brief parts of the story, not so different from modern rubberneckers. The animalistic desperation of the sidewise spirits, and Bessel’s terror on realizing what’s happened. The silence of the sidewise world. The true horror of the asbestos bricks—well, no, Wells couldn’t imagine how that would come across to the modern reader.

Becoming aware of dimensions adjoining our own is always dangerous. Sometimes it opens you to attack by things that can only see you when you see them. Sometimes it merely provides knowledge you’d have been happier/saner/kinder without. There’s more danger here than mere awareness, though it does seem like some effort is required to make oneself vulnerable. Project your mind astrally, though, and your body is free for the taking.

The things that take it are disturbing: creatures of violence and passion, desperate for embodiment and life, incapable of real motivation beyond that desperation and the momentary overwhelm of physicality. “Life!” Like Hyde’s rampaging delight in the Jekyll and Hyde musical, rather than the cold calculation of a visiting Yith or long-term political calculation of Joseph Curwen. If anything, they remind me of the Jewish shadim, who are sometimes said to lack bodies, and to cause illness in those whose warmth and life they steal.

The suggestion that mental illness is caused by possession is not unique to Wells, but not one of his more progressive suggestions. Also not original to Wells is the idea of the pineal gland as the seat of supernatural perceptions and abilities—apparently that’s Descartes’s fault. It responds to light because it’s related to circadian rhythms, not because it’s an eye in the depths of the brain. Generations of modern neuroscientists would like a word.

I’m willing to forgive a lot, though, for the image of spirits crowding around a medium, trying to touch her brain for a moment of communication, hoping that their moment coincides with a flash of power and clarity from her fluctuating inner eye. Shades of Beyond Black, seen from airside—I do hope Mrs. Bullock is having a better time than Al.

Next week, we meet more of the road trip gang in Chapters 3-4 of Max Gladstone’s Last Exit.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of A Half-Built Garden and the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon and on Mastodon as [email protected], and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.