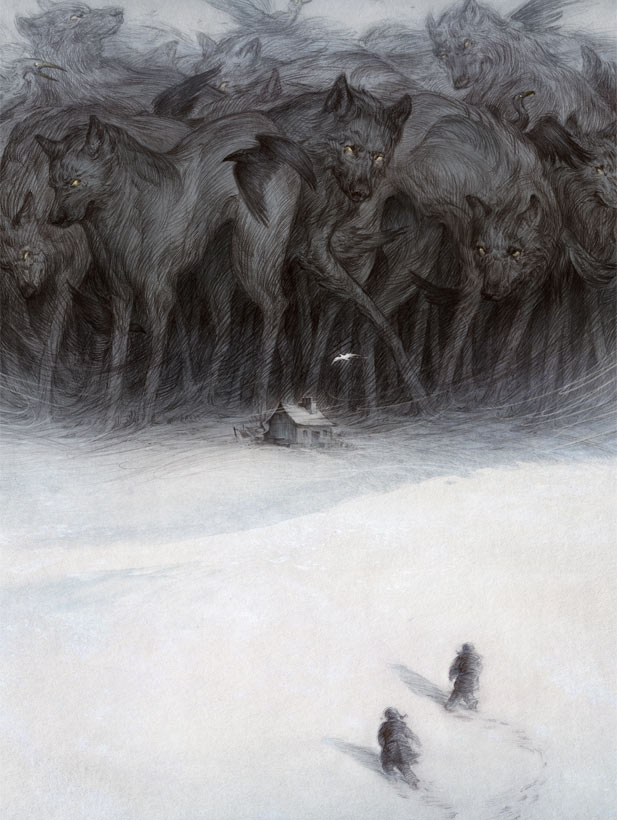

Young Tom has always dreamed of wolves, which everyone knows don’t exist. One day he goes out for a log from the woodpile, and when he returns, there is another Tom, like him, but other. This dark and compelling tale from short fiction writer K. M. Ferebee will make you reconsider what may be lurking in the forest.

When Tom is seven years old, he dreams of wolves. He lives by the woods. His father is dead. His mother takes in washing from the little town of Leynmouth. Washing is how we make ends meet, she says. In the mornings she washes, and she listens to the wireless. The radio reports the forecast from the North Sea. News comes on after, when Tom’s mother is hanging the washing. Great white sheets shape themselves up and out into sailcloths. They rage over the thistles, the prickly sedge. Far off is the forest they wish to escape to: pines and pale beech and the bulk of yew trunks, a wall of wet-smelling woodland. A threat of further trees that the ridge line holds back. Tom wonders why the sheets want to sail to it. He marvels that the clothes-pegs can keep them contained. He runs through their coiling, sinuous caves. His mother calls, “Don’t dirty up the washing!” Tom lies in the grass, squinting happily upwards. Sometimes an aeroplane goes past, its metal body buzzing, no bigger than an insect. When his mother sees this, she looks weary, and says, “Thank God the war is done.”

Tom ponders the aeroplane. It outpaces the black wood. From the eye of the aeroplane, the woods must seem a gap, a small slice of shadow that cuts along green country. But Tom knows that the woods are not small or large. They have no shape. Their size is other than this.

On Saturdays, he walks with his mother to town. He is entrusted with the washing money and the ration book. He shows their coupons for milk, eggs, and sugar. The shopkeeper tears them out of the book. “Young Tom,” he says. “Wouldst like a summer apple?” He puts a small red apple in Tom’s fist. It is soft, and it tastes of tea with honey. The shopkeeper says, “I trust you’re staying out of the woods.”

“He’s a very good boy,” Tom’s mother replies. Tom hides behind her skirts. The truth is that he is afraid of the forest. He dreams of wolves filling it. Fast silver wolves, loping and silent. They slope between the evergreens and birch. They pant into air grown sweet with frost. They go in packs. Their eyes are gold. Their backs are brindled. “There are no wolves in the wood,” Tom’s mother tells him, when he complains about these dreams. “Where have you seen a wolf, you silly boy?”

He knows wolves, of course, from fables. From fairy stories. They drag huntsmen to their lairs, or drive bargains with princes, or hide in little children’s beds, ravenous at all times and deceitful, thinking of nothing but how to eat men. His dream wolves are indifferent to him. He stands in the wood and they whisper past, their paws churning up the snow-scrim. He tells his mother, but she does not perceive the terror the wolves inspire in him; she draws him close and wraps him in blankets and says, “There are no wolves in all of England.”

Tom wonders why his mother would tell him a lie. He turns his face towards the blanket. He can hear the wolves out in the forest. Their broad paws leave prints. They let their tongues loll. They turn their bright eyes towards him.

It is well into November. They are trudging hillwards at the lane-side. Tom’s shoes slip and glance off the patchwork ice. Night is coming on, quick and sullen. For no reason at all, Tom feels afraid.

“Hurry up!” his mother says, too sharply. Her face is pale. Her nerves are frayed. Winter is hard. The shopman says, “No credit.” Tom has not grown much since his last birthday. He is little and shy and not prone to speaking. “Keeps himself to himself,” is what the neighbours say.

Up ahead, the outline of their cottage looms. “You run ahead and light the stove. Put the kettle on,” his mother tells him.

Tom heads for the woodpile at the back of the house, closer to the forest, where the verge holds sway. Come spring, the forest will slink from its boundaries, and Tom’s mother will have to hack at its limbs: the outbursts of field dock in bloody colours, thin fingers of oak reaching out of the grass. Now all is deadened by ice and shadow. Twilight’s damp brush tars the air blue-grey. Tom reaches towards the firewood. He feels a rush of superstition. He hugs a log to his chest. He does not want to look towards the forest. He hears a crackle. He hears feet crisp on frost. He freezes.

He sees a shadow cross the wall, a thing of not-here-or-thereness, like a person’s body without any bones or meat. It comes very close. He feels its hot wet breath. He smells damp fur and raw flesh and dead leaves burning. It is a death-in-winter, carrion scent. Something touches his shoulder. He shudders. A black feather whiskers past him and curls at his feet. Whatever it is that stands behind him sighs: a long, slow, drawn-out sound of grief. Then it is gone. It steals back to the forest. Tom listens until he can no longer hear the cold little bone-like crunch of its feet. He stands in the darkness for a long time. His heart pounds and his hands tremble.

After a while, he knits up his courage. He hurls himself towards the cottage door, not stopping to see what haunts after. He clutches the firewood so fiercely that a splinter works into his finger. There is hardly any blood, but still a wound has been started.

When he reaches the door, he runs inside. His breath is rattling out of his body.

His mother is storing the shopping on the shelves. The kettle hums amidst clouds of white steam. But when Tom’s mother turns and sees him, her face goes colourless; she drops the apple that she’s holding. Her hands fly to her mouth. She says, with horror in her voice, “Tom?”

Tom feels tears slide down his cheeks. He can’t understand his mother’s reaction. Nor can he bring himself to speak of the wintry creature out by the wood stack. He hasn’t the words to try to describe it; not half of the words he would need.

His mother says, “But if you are my Tom, my own Tom—” She comes close and her hands roam his cheekbones, his ruffled fair hair, the rough fabric of his sleeves. “—and, oh, my darling, you’re cold as death—but if you are my Tom, then who’s that boy in your bedroom?”

She runs to the bedroom: a sharp, sudden motion. Tom trails behind, uncomprehending.

There, by the woodstove, another boy is sitting cross-legged on Tom’s little bed. He has the same pale hair as Tom, the same round shape to his features. His eyes are cornflower blue, like Tom’s. But a restless energy hangs about him: like a wolf about to spring, or a storm building over the land, steeped in electric voltage. Tom thinks, I am not like this. How could you think this boy was me?

The boy looks at Tom with no expression. He shows no curiosity. He blinks very slowly, like an animal. His hands make little fists around the sheets.

Tom’s mother touches his shoulder. He can feel that her pulse is racing. “Come away,” she whispers. And they leave the boy there. They tiptoe meekly out of the room, back towards the kitchen.

For a time, his mother is on the telephone, talking to the rector and then to a priest. She talks in a harsh and violent whisper. Tom can hear the voices of the rector and the priest: plain, flat, calm, denying. At length, the phone goes back on its hook. His mother covers her face with her hands. Tom sits at the table. He tries to be still. He says, “Can I have something to eat?”

He is given bread with butter and jam. He licks the seedy jam off his fingers. He is mouse-quiet; he can see his mother is thinking. He cuts more bread to toast over the fire.

The other boy comes creeping, step by shuffled step, from the hall. Out of the corner of his eye, Tom sees him, but does not react. He simply stares straight ahead at the fire. The bread gets brown and hot and smells of warm grain sweetly roasting. The other boy licks his lips. Tom ignores him. He spreads the bread with yellow butter—on any other day his mother would reprimand him for eating up all their ration—and deep-red strawberry jam. The jam and butter melt together. The other boy holds out his hand.

At first Tom resists. If he is hungry enough, he thinks, he will go eat someone else’s bread and jam. But he is a lonely child. He has no playmates. He has often wished for a sister or a brother who would go with him to skim rocks off the shores of Loch Leighin; who would lie in the grass staring up at the clouds and say, “Look, that one is like a rabbit,” and point out aeroplanes as they pass. All this Tom wants, and though he feels a sullenness at seeing the boy look so like him, he still cuts a slice of bread from the loaf. He warms it briefly over the fire, and carpets it with butter and jam. He holds it out, the butter leaking on his fingers, and the other boy snatches it from his hand.

The boy wolfs the bread down. He eats like a savage. This is something Tom’s mother says: Close your mouth and chew your food. Don’t eat like a savage. But the boy forces his food down fast. His mouth hangs open. When Tom offers him more bread, he tears into it, then scuttles in close to stick his hand in the jam pot. He eats in fistfuls, bread and jam.

“Don’t do that,” Tom tells him sternly.

The other boy stares at him wide-eyed. Perhaps he has never had someone to tell him how to chew his food, someone to butter-and-jam his bread. Patiently, Tom shows him the whole process. Then: how to measure out tea, prime the kettle, pour the milk, dip his bread into the warm-smelling mixture so that it is soft in the mouth and delicious.

By this time, Tom’s mother is watching. She sits in the corner, her arms gently folded. She seems tired now, and not very angry, though her mouth has the unhappy curve it gets when her nerves have been stretched to their end. When it is late—far past Tom’s bedtime—she gathers the two children and tucks them side-by-side into Tom’s bed. She sits by the woodstove. Embers are burning. She tells a story about twin ravens that sit on a wise king’s shoulder. One is called Dreaming, and the other is Thought: that is what she says. Tom is lulled by the sound of breathing that is not his own. He watches his mother bend close to the stove-side. Its cinderous lighting turns her hair red. She is still speaking, still telling a story.

Tom does not dream of wolves. When he wakes, he sees the other boy beside him, sleeping soundly, halving the bed.

The next day, Tom’s mother asks over breakfast, “Where did you come from? Who is it that brought you here?”

The boy says nothing. He stuffs bread into his mouth, and beans, and eggs. He stares at her with a dumb, silent expression. His eyes don’t look blue anymore. By afternoon they have turned gold instead: a dark green-gold that is strange to gaze at. His face, too, has changed, grown thinner. He looks gaunt. His hair curls fox-red. Tom accepts these alterations. He is not bothered by the shape-changing. It is a relief, in fact. He had found it strange to look at his reflection. Now the boy is merely a boy: Tom’s brother.

Leynmouth’s rector comes by the house that morning, and later on the Catholic priest from St Sadde’s. They both have cursory words with Tom’s mother. They drink their cups of tea and pat Tom on the head. They ignore the other boy. Politely, they chat with Tom about what he would like for Christmas. When they leave, Tom’s mother slams the door behind them. She looks like thunder. She gets on the phone again at once. In an hour a stranger knocks on the door: a white-haired, wizened, age-smelling old man.

“I am the man you wanted,” he says to Tom’s mother. He is wearing a stained coat and a broad-brimmed hat.

He peers at the boy who is not Tom. The boy who is not Tom peers back, his gold eyes dense, flat, and guileless. He touches the brim of the old man’s hat, as though he has not seen a hat before. The old man says, “And what is your name, my lad?”

“Tom,” the boy confidently answers.

Indignation rises in Tom. “It isn’t ever!” he says. “Tom’s my name. Your name can’t be that.”

A cloud of doubt flickers over the other boy’s face. “Tom. Tom,” he says again. There is a tone-deaf timbre to his voice. Tom wants to hit him.

“Tom,” Tom’s mother hurries to interject, “he likes your name so much. Perhaps you can share it a little? You can be Tom without an h, as you are, and let him be Thom with an h in. You remember what I have told you, that sharing is the act of a gentleman.”

Reluctantly, Tom subsides in his chair. He glares across the table at the new-labelled Thom. Thom gazes happily at him.

The old man places his hand on Thom’s head. Thom’s red hair curls up under his fingers. The old man winces and grimaces. “Yes,” he says. “He is one of them.”

“And you can say that, can you, with just a touch?”

The old man taps the side of his face. “There’s some have the sight, and some have it deeper, the sight that goes down under your skin. I tell you now, he is a child for the woodpile. But fetch iron if you will, a horseshoe or skillet.”

Tom does not know what a child for the woodpile is. He does not like the thought of it; he thinks of the splinter in his finger, the smell of cut wood, the single drop of blood coming out of him. He watches the man reach into his coat pocket and rummage about as though looking for a stray sixpence. Indeed, he does pull out a sixpence, and a bit of sea-glass, and what looks like a bird’s bone, then a tin toy soldier and a rusted iron nail. He lays them out on the table in front of Thom.

Thom examines the objects curiously. He gives cursory attention to the sixpence and the toy soldier; he hums when he touches the piece of sea-glass; and when he sees the bird’s bone, he chirps like an infant kestrel. But the nail—the nail receives his full fascination. His eyes open wide, as though he’s seen a rare piece of treasure. His breath comes short. After a moment’s heavy covetousness, he reaches out to snatch the nail up.

For a moment, Tom does not recognize the sound Thom makes as shrieking. It sounds like an animal-sound or a bird-sound. But then, most things sound the same when they are wounded. And Thom is wounded: his hand is burnt, as Tom sees when his mother gently uncurls Thom’s hand. The nail has left a mark: a charred white line of dead flesh.

“You see,” the old man says, sounding grim. “Cold iron. He cannot resist it. I tell you, that one has the curdling power. He’ll sour your milk and set fire to your washing. He’ll bring the birds and wolves to your house.”

Tom’s mother stands for a long time, looking. Tears drip down Thom’s pointed chin. At last, Tom’s mother goes to the cabinet. She fetches butter and herbs and cloth. She binds up Thom’s hand where the burn is welted. She smooths her fingers through his curls and says, “Now, we’ll have no more caterwauling,” which is what she says to Tom when he has fallen down and scraped his shin.

The old man turns a fierce countenance on her. “And what if your own child was dead?” he demands. “Or taken off in the woods, under the hills, and you not to see him again? Would you so happily take a changeling, then?”

So there: the word is finally outened. Tom knows its meaning very well. Every child in Leynmouth is taught to beware those other folk that used to live in the wood and are but lately gone; or that linger, maybe, under the ground; or that wait for their name to be said unawares so that they can then come into the world. Their state of half-being arrests people, scares them. And children know that what those folk love is to steal a child of less than ten years, and to leave in its place their own sickly child. That false child will fail, and die, and be coffined. What becomes of the real child: unclear. He goes off into the woods with them, never to be seen again. Meanwhile, the changeling takes his place, dies here in his stead.

So that is Thom: the changeling. The other folk brought him. Tom sensed them, smoke-like in the lengthening shadows. They sighed in the night; they smelt of the winter. But they left Tom behind. They did not take him. He stares down at his hand, at the splinter still bedded in his finger. The blood has dried. The pain remains. Why, he wonders, did they not take me?

His mother murmurs, “Dear, dear.” Thom’s head rests against her arm. Her warm hand still strokes his red-gold hair. Perhaps Thom has never had a mother. Who knows, Tom thinks, how those folk live there.

“You’d best put him out,” the old man warns. “What life is there for such as him here? No life at all. His own folk did not want him. He brings death into your house.”

“That’s enough,” Tom’s mother says. She stands up, very flashing-eyed. “Put him out or no, it’s my business. You’ve done what you came to do, and spoken. Now you can leave again.”

Tom has never seen her hurl someone into exile before. The old man pulls his coat back on and puts his cap on his white head. He gathers up his trinkets and exits the house with hard, hobnailed footsteps. But the iron nail, he leaves on the table behind him. Tom’s mother takes it and turns it between her fingers, with a hard expression, as though it were something distasteful, something dead.

She puts it into her pocket and sits down by Thom. He curls up beside her. He has stopped weeping, though tears blotch his skin. All at once, Tom’s mother looks very tired. She says to Tom, “Would you mind so much, having a brother, just for a little bit?”

Tom examines the sleepy face of Thom. His dangerous eyes are heavy-lidded. Before, when the touch of iron had burned him, he had looked at Tom just for an instant. A look of betrayal, a look that said: You let me be hurt. You, myself, my kin. Now Tom feels a certain demand. The weight of it presses down on him, some kind of oath he’s already sworn without realizing it. We are brothers, he thinks, and it can’t be helped. I will not let you be hurt again.

To his mother, he says, “But will he talk? Will he order me about? Will I have to be nice to him?”

His mother smiles. “Perhaps. I don’t know yet.”

“When he gets older, will he go back to his kin?”

Then the smile droops. “We must never speak of that, Tom. Not to him. Not to anyone. Do you promise?”

“I promise,” Tom says. He would not like it if someone reminded him that he had been left on a stranger’s doorstep, that his folk had crept home through the night without him. That would be hurtful. It would break the oath he has sworn, an oath between brothers, vague and solemn.

All the same, he senses that this new promise will not stand for long. He already presses against his limits: swollen with secrets that stretch his skin. He looks at this frail thing, his little brother. This not-quite-human bundle of limbs. He should feel love. Instead, he feels tired. Unequal to the task. Somewhere deep inside him, a twinge of dread begins.

Since the war, the folk of Leynmouth have not been so superstitious. Still, they have lived a long time with superstition. All their lives have been steeped in it, spent beside the peril of the forest. At times, along the ridge of the almost-black woodline, dogs and birds have been found dead. No one can say for sure what killed them. And so a certain legend resounds.

It is no surprise, then, that word gets around about Thom. When Tom and Thom go into town, other boys throw rocks at Thom’s head. Very small rocks, ripped-up road rubble, but hard and sharp-edged. Shops close their doorways, shutter their windows. “Sorry, my lad,” says the shopkeeper, who, in summer, had given Tom an apple. “Best go elsewhere. Bad for business.” He acts like Thom is not there at all, like Thom is a shadow that Tom casts.

“They think that your brother will rot their apples,” Tom’s mother says, when he comes back and tells her of these proceedings. “They think he will cause their milk to curdle, and crack all the shells of their eggs.”

When Thom comes back from town bleeding at the eye, Tom’s mother forbids them to go back to Leynmouth. “I’ll do the shopping till they find their senses,” she says. Still, trouble finds its way up to their doorstep. There are notes tied to bricks tossed through the window. There are straw crosses, and holly branches bound with white thread. These are signs to keep off the Devil. There is the dead bird that Tom and Thom find nailed to the broad painted wood of the door, its eyes like filmy black ice chips, its fine-boned wings outspread.

It is not clear to Tom how much of this Thom understands. Thom will say only their shared name. He says it for all communication. He cries when hurt; he cries over his burnt hand, though Tom’s mother rubs beeswax salve into it and sings him nursery songs made up of nonsense.

At night, when the two of them are tucked up in bed, she tells them stories. She tells them of the great king under the mountain who sleeps with a mistletoe sprig through his heart and a crown of holly berries on his head.

The midwinter nights grow long and spiny as frost. Snow compounds snow with its odd permanence. Tom starts to dream of wolves again. Now, though, when he wakes in the night, Thom is beside him. Often, he is not sleeping. Tom thinks, He sees into my dreams. That is what wakes him. He wonders if Thom has dreams of his own. Perhaps he does not, and they share Tom’s dreams.

One night, not long after Christmas, Tom wakes from the same wolf-troubled dream. In his dream, the snow is up to his knees. The wolves are passing all around him. They are as tall as he is, fast and sleek. Their eyes are dense and gold as birds’ eyes. They shake the snow off their pelts and pace on either side of him. He curls in the snow, brought low by terror. He hugs his arms around himself. Just when he smells the woodsy, rotting wolf-breath and feels its warm damp on his skin, he snaps awake.

Thom is watching him. In the dark, his eyes look like amber. He says, “There are no wolves in the wood. So why do you dream it?”

“I don’t know,” Tom says. “It’s just a dream.”

He turns on his side and resumes his sleep.

In the morning, when Tom wakes again, Thom is still talking. He goes on talking in a not quite natural manner, as though he is pruning the words from some overgrown tree. When she hears Thom at the breakfast table, chatting carefully, Tom’s mother drops her coffee cup. But all she says is, “Would you like some more sausages? Tom? Thom?”

Thom says, “Yes, please.”

For the rest of that winter, Thom practises speaking. He has a strange way of speaking in stories. Perhaps he has absorbed it from long nights of Tom’s mother’s fables. Perhaps it is how his own people speak. If Tom says to him, “Look where that old crow is sitting! I bet I could strike him from his tree with a pebble,” Thom is apt to respond, “The old king Mark had a daughter who kept ravens: Forthright, Sanctity, and Seacraft. So she called them. Each one would fly around the world and say to her exactly what it had seen. And if you said a wrong word to her ravens, or shook a weapon, and if her ravens hapt to see, then the daughter of King Mark would come to you at night.”

“And then?”

“Then she would curse you. So your heart would turn to a piece of seed, and one of her ravens would pluck it up.”

“Mum says there’s no such thing as curses,” Tom says, but all the same he throws no pebbles at the crow in the tree.

Another time they are trudging, as they often trudge, through the snow round Loch Leighin’s boundary. Winter is no bar to Thom. He likes the cold, and will carelessly leave his coat and hat until Tom’s mother runs after: “You’ll catch your death, what are you thinking?” Thom will allow her to button him into his coat—but then loses his mittens or scarf, shedding them indifferently.

Tom doesn’t care for the cold. It hurts his bones. But he can’t admit that without wounding his infant bravery. So instead he walks with Thom along the woods and the icy lakeside. “In summer there are fishes,” he says to Thom. “In summer there are flowers. I carry my rod and catch the fish. I lie in the grass and I count aeroplanes.”

“What is ‘aeroplanes’?” Thom asks him.

“Where you come from, don’t they have aeroplanes?”

He realizes that he has broken his promise. He is not meant to ask about where Thom comes from, an inhibition imparted daily by the climate of chill round the topic. He wishes the words back, feeling shame.

But Thom looks at him calmly. “The old king Tistram had a beautiful son. More beautiful than all the world was the son of this king. But he was alone, since no one in the world could match his beauty. He grew sad and sold his soul to the sorcerer Lopt, who gave him a white seabird’s wings. Tistram’s son thought he would fly from this world. But it did not work. He was too heavy.”

“So what happened?”

“He fell to the earth and died. But the earth would not bury him, because of his beauty. So it gave him to the sea, but the sea would not bury him, because of his beauty. So it gave him to his father, the old king Tistram, who placed his son’s body in a place where the birds could come and eat. So all the birds of the world came and ate him up, and were more beautiful for it.”

Tom says, “That’s a horrid story.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. Can’t you see why it’s horrid?”

“No.”

Sometimes Tom thinks Thom seems much older than him. They are the same size; they have the same bedtime; often Tom will recognize an object—a lamp, a motorcar, a coal scuttle—and Thom will not know what it is. As though Thom is an infant, new in the world, where Tom is old and confident. And yet Thom will tell stories rife with corpses, with broken swords and madness. Thom’s stories have ghosts and gruesome trials, sad gods; they end in suffering. Sometimes they have no ending at all. They are not proper stories.

“When it’s summer,” Tom says, “we’ll stay outdoors forever. I’ll show you the aeroplanes then. You’ll see. They look like birds.”

“Summer,” Thom says.

He says the word in a way that suggests it’s foreign, like wireless, petrol, telegraph, heat. Tom wants to ask, Is there not summer where you come from?, but it seems an absurd thing. Summer is not set to one location. There is summer in the woods and summer in Leynmouth; there is even summer in the mountains to the north. Green surfaces and spreads across the dead grass of hillsides. Gorse shows where the frost has been. There is nowhere on earth immune to summer.

That night, when Tom wakes from his wolf-dream, Thom asks him, “Why are there always wolves in your dreams?”

“I don’t know.” Tom hunches his shoulders inwards.

Thom says, “I don’t dream.” It sounds like a secret, something confided to the air that their shared breath heats.

Tom asks, tentatively, “Where you come from, do the people not dream?”

“We don’t sleep. Not like you do. We might sleep for a season, or for a whole century, maybe.”

“For a hundred years?” Tom cannot believe it.

“We get tired.” Thom’s eyes flicker.

“Do you miss the place that you came from?” Tom asks him.

Thom tells him a story. “When Prince Uther was still in his regency, he fell in love with a night-blooming flower that grew upon the King of Arth’s barrow. So he changed the flower into a young woman, and she was very pure and fair, and he carried her off to his own splendid castle. But so strong was her own nature, so great was the sympathy of earth and root and stem, that the flagstones of Uther’s castle cracked under her footsteps. Every sort of sapling broke through the stones. Brambles overtook Uther’s towers, and a river rose up from the seat of his throne, and a multitude of strange fish swam in it, and great beasts lumbered in the shadows of the forecourt. And though the young woman could never again be a night-blooming flower, she could rule over all of this.”

Silence hangs in the still, dark air. “I don’t understand,” Tom says.

Thom shrugs. He fingers the scar on his palm. “Sometimes I don’t understand things that you say.”

Tom senses it is not the same somehow. But he does not know how to say the difference between his descriptions of gas stoves and kettles and the strangeness of Thom’s stories. Instead, he says, “Do you not mind when I ask you about it?”

“Why would I mind?”

“Mum says I shouldn’t. You might be sad. That’s what she thinks.”

Thom blinks slowly. His eyes are wide, bright, foreign. He says, “I’m sad anyways.”

After that, they talk often about Thom’s homeland. They talk about it quietly, in secret, so that Tom’s mother won’t hear them. She’s the one it would make sad, Tom thinks. This must be the logic to her prohibition. For Thom does not mind the talking-about-things. He will go on at length, lost in description. Tom learns that in the land where Thom lived, there is not bread, or milk, or even bacon. There aren’t even apples—“not the kind you have here, white when you bite them. Only gold ones that taste like cold, sweet water.”

“That doesn’t sound very nice.”

“You haven’t tasted them.”

Even the water that runs through Thom’s homeland is different. It is white as snow, and very pure. “But cold,” Thom says. “Everything is cold there.” The nights last for thirteen or fourteen hours. Sometimes there are nights that go on for years, and no one can predict when they will come. One day the sun does not rise in the east, and then you know that night has come. The sun travels elsewhere. The birds stay asleep. “We have, in my home,” Thom says, “many birds. They sleep all through the long, long nights. But when the sun’s out, they sing in mortal words, and tell us our fortunes, and speak with our gods.”

Thom is astonished to learn that Tom thinks himself uncomprehended by birds. “You are just not singing to them right. Listen.” He whistles, low and complex. A dark winter bird, something close to a crow, echoes it back from the branch of a crooked sapling. Tom tries, but he can’t make the same sort of bird sound. He feels a hollow resentment grow.

There are times when Tom wonders if Thom’s being entirely truthful. Tom’s mother has told him not to tell lies. The Devil is the breeder of lies, she tells him. He pictures the Devil: a beekeeper in a back garden, keeping and tending his hives, while lies fly out in little black swarms, wild and venomous and alive. That is what a lie is like, in your belly. When you spit it out, it puts its sting in your tongue, poisons you as it takes flight. So he does not lie if he can help it. But Thom, he thinks, Thom might lie. In Thom’s stories of his homeland, there are always sweet apples and red grapes and wine, and milk, and tree-sap-coloured honey, and a kind of warm syrup that smells of pine. All of the men there feed on nectars. But Tom has seen Thom at supper, and knows he sucks the marrow out of beef bones. He likes lamb shanks. He delights in the pinkest part of the meat. He drinks the bloody juice from his plate. Tom can’t imagine him drinking wine, or eating fruit steeped in flower water. He remembers the carrion smell at his shoulder when he stood at the woodpile that November night. That was the smell of a hawk or a vulture. A hunter. So when Thom describes the mild tastes of his homeland, Tom thinks, Are you lying?

Once, after Thom tells him how each tree in the forest used to be a courtier under the old king Gawain, and each courtier in turn asked the king for a gift, and that gift was the gift of never dying, and the old king Gawain made it so that they would not die, but would live forever in the bodies of trees . . . When Thom has finished telling this story, Tom turns to him and asks, “Did you make that story up?”

“What do you mean?”

“Are you lying to me?”

Thom doesn’t blink. “And what if I was?”

“The Devil is the breeder of lies. You mustn’t tell them.”

Thom considers this statement. “Why not?”

Tom flounders. The conclusion ought to be obvious. Yet Thom appears not to see; he stares at Tom and waits for an answer.

“I don’t know why,” Tom says. “You just shouldn’t tell them.”

When no further answer is forthcoming, Thom turns away. A sullen air settles on him. “Where I come from,” he says, “the Father of Lies is our favourite god. Every year there is a festival devoted to him. Everyone tells all the lies they can and their lies become more and more beautiful. At the end of the festival, the man who has told the most beautiful lies gets a gift.”

“What does he get?”

“His lies become true.” Thom scuffs his foot against a snow bank. He squints up to where the sky is barraged by birds. The birds are black, and then all at once they have left. The sky is white where the clouds blunder low. All other colour has been leached from that landscape. Thom alone stands out from the snow, with his wolf-like eyes and his wild red hair.

By the time the snow starts melting, Leynmouth similarly thaws in its treatment of Thom. No longer are there stones aimed at his head, though the shopkeepers hold fast—Thom may press his face to the glass of their windows when they’re not looking, but they will not let him in.

“Could you really,” Tom asks him, “curdle their milk? If you wanted to?”

“I don’t know,” Thom says. He appears uninterested in the subject.

“Could you crack the shells of their eggs?”

They are walking through town. Thom stops at a window. He leans forward. His breath clouds the glass. His boots scrape the pavement. It is the butcher’s shop, where several half-pigs hang in the window: skinless, their bones exposed. The white fat on them glistens.

Tom swallows. He does not like to look at the pigs. He thinks of the wolves tackling prey in the forest. He thinks of the things that older boys have said about what happened elsewhere in the war. “Never mind,” he says. “Let’s go.”

Thom doesn’t move. He licks his lips. He is more than usually hungry, since winter began to fade. The new warmth seems to make him leaner. The longer sunlight thins him down, makes his face look sharp, his arms like sticks. “When the sorcerer Lopt was a child,” he starts . . .

“Never mind,” Tom says again. “I don’t want you to tell me a story.”

“I thought you liked my stories,” Thom says. For an instant, a look of despair crosses his face; ends Tom’s impatience. Tom reaches out to touch Thom’s hand. He thinks to himself: Kin. He feels the white scar that bands the palm there: Not kin.

They walk home through the mud streets of Leynmouth. The snow-melt turns the fields into fens, segments the earth in splinters and shudders of rivers.

That evening, when they are dressing for bed, Thom pulls an unbroken egg from his pocket. Perhaps he has stolen it from the kitchen. It looks like quite an ordinary egg. Thom holds it flat, balanced in his palm. “It’s for you,” he says. “A gift.” He is whispering: this is a transaction between them.

In Thom’s palm, the egg begins to crack. First the fragile china skin splits, like the crust of ice on the lake when springtime erupts from under it. Thom holds his hand still and lets the egg shudder. A little gilt beak comes out of it, and then the curve of a wing, pearl-coloured. A bird pushes out, bit by bit: not a dull, plain bird, like a goose or a chicken, but something iridescent. Its eyes are amber-gold. Its silver wing-tips are sharp. It is so small that it can fit entirely in Thom’s palm. Tom watches its pinprick claws flex and curl.

“Oh,” he says. “Can I hold it?” He keeps his voice quiet, so as not to scare the bird.

Thom shifts the bird out of Tom’s reach. “Only I can handle it. If you were one of the folk of my country, then you could have one of your own. In my country, the air is full of them.” The bird blinks and makes a cooing sound. Thom holds it close and strokes it.

“Can we keep it? We could keep it in a cage in the corner.”

Thom doesn’t answer. He carries the bird to the window and undoes the latch that sticks the pane shut. A gust of raw wind gets in, smelling of places where the ice is still thick on the ground. Thom slips the bird out the window. It clings to the ledge. He whispers to it, bending close. He whistles. It takes flight: wings like knives in the darkness.

“It’s too cold for birds,” Tom says. Resentment prickles. “And I wanted to keep it. Now it will die out in the wood.”

“No,” Thom says. “It will live.”

“Will it go back to your kin, to the people in the forest?”

“Yes. Or hunt in the dark.”

“Will you go back to your kin?”

Thom breathes out against the window. His breath leaves the glass frosted. He puts his pale hands there, paints warm, empty prints. He says, “I can’t go back. I don’t know the way back.”

“Back through the woods?”

“Yes. It’s a long, hard journey.”

“Will you stay here with us, then? Forever?”

Thom sighs and climbs into bed. “Forever?” he says. “Here is a story about forever. In the reign of the old king Eothred . . .”

Tom waits for his mother to bring them warm milk and pull the blankets up over the bed. He does not pay attention to the thread of Thom’s story. Thom’s voice is hoarse. It sounds thin. Tom watches as moths lay siege to the gas lamp. Their wings are soft. The light makes them look red. They make a sound like birds in the dark. Their shadows seem to reach out, covetous and insubstantial. He shifts, very nervous, just for a moment.

“That is what is meant by forever,” Thom says.

Thom coughs a great deal through the end of winter, grows ever more hungry. He is listless by the time that spring begins. But he was pale before, and always starving—always small in Tom’s cast-off clothing, always a little too thin. And, anyways, this is the sickening season. Tom himself gets ill, and then gets better. There isn’t a name for what ails him—just illness. So it is with Thom. Tom’s mother says, “He’ll come out of it.”

But Thom doesn’t. The days drag on. The air warms and the wind thickens, bringing rain up from the south, bringing mayflies that die on lamps. Thom is hot, often feverish. In the late bluish evenings, he lies in bed. He tires very fast during the day. He lies in the shade, his eyes slack-lidded.

“Is this summer?” he asks Tom one day. They are out in the garden. In spite of the weather, the trees are still bare. Come a fortnight, they’ll all clot up with blossoms. Tom can see it on the branches, all the dark buds there.

“Not yet,” he says.

“It’s so warm here.” Thom lets his head drop back to the ground. They are both lying in the flat grass. Tom can smell the growing heat that will backbreak the winter, the spring coming up from under the earth. Birds are returning, too, from their travels: crowds and crowds of sparrows, and swallows overflowing with song. He wonders what Thom understands of their noise. From time to time an aeroplane soars past, larger and farther out than a bird, and Tom points it out, but thinks, Thom does not really care.

He resents Thom’s sleeping all the time. He does not like the worry with which his mother stares at Thom when she thinks that no one is looking. He has heard her on the phone to Leynmouth’s doctor. He has heard her crying in the other room. He regrets his impatience, his small resentments. He wishes for an end to Thom’s illness.

“When summer comes,” he tells Thom, “we’ll go into the woods. We can find the place that you came from then.”

Thom doesn’t reply. He plucks at the grass. Where he closes his hand around it, it withers and dies. He seems oblivious to this.

“We could go now,” Tom says, “but I am frightened of wolves. They roam in the winter.”

“There are no wolves,” Thom says. “Not here.”

“Do you really mean it when you say that?”

Thom looks at him. “Wolves only live in other places. Dark places. Here they’re a story to frighten you with.”

Tom wonders: Am I frightened? He is frightened, yes. He wants to hide from them. But now when he dreams of wolves, there is another instinct. He wants to bury his face in their thick grey fur, to feel their warm pelt under his cheek and breathe in that strong rank wintry smell.

He doesn’t tell Thom this. He asks instead, “Will you be happy there? If we find the way back to your country? It won’t be as warm as it is here, will it?”

Thom shifts. He stares up at the clouds as they scud through the air, pursued by sunlight. “No,” he says. “It will be winter. It is always winter there.”

Thom begins to cough in spasms that unsettle his small body. At night, his coughing shakes Tom awake. He sees Thom’s bright eyes right upon waking, and wishes he could go back to sleep. Their bed is increasingly filled with feathers: white feathers, soft as down. Tom is not sure what they mean. He likes to think that the white bird Thom hatched comes back to visit while they sleep, and breathes out the air of that other country where winter is everlasting. He pictures its wings, now speckled like eggshells. Its breast is frost-coloured, pure and clean, and it sings a song like the wind on the mountains. It digs its claws, its hard bone claws that have been hunting, into the bedpost. Its song is also a hunter’s song, and when Tom imagines it, he feels his heart seize. He thinks, I have not heard this song before. But I have waited all my life to hear it.

He suspects that, in reality, Thom coughs up the feathers. It is a part of his sickening. Tom has never coughed up feathers whilst ill, but it seems possible that this is how folk sicken, off in the wood, off in that other country. He says nothing. He sweeps up the feathers. Off they go: out the window, into the warming breeze.

“Will Thom die?” he asks his mother. This, too, seems possible. He has a notion of dying. He has seen animals dead in the fields. Dying is what his father did in the war. He wonders if men are like birds and sheep, if when they die the flesh goes off them till they are just bones you turn up in the weeds. Bones, white and rough and thin. He thinks that men cannot be like this. Men are men. They are not made of the same stuff as birds and sheep. There is something else to them.

His mother says, “I don’t know, my darling.” She does not reassure him. Neither does she remind him of what legend says: a changeling is not put in the world to live. They have not spoken of this before, though it hangs over them. Nor do they speak of why those folk did not take Tom. Tom thinks, sometimes, about that animal breath. His finger hurts where the splinter pierced it. He thinks of the single black feather drifting past him.

Now Thom eats only bowlfuls of beef broth. He is only bones and skin. He lies in bed and his breath is a rasp. Tom’s mother cleans Thom’s sweat off him. She collects the feathers that rise from his mouth, and she does not ask questions. Except: “Should I take you homewards?” which she asks more than once. Mute, fretful, Thom shakes his head. It is not clear that he knows what she’s asking. He mutters often to himself, but Tom cannot understand what he’s saying.

“He does not know the way back to where he came from,” Tom tells his mother. He feels important. Thom entrusted him with things that she doesn’t know: with stories, with secrets.

“Does he not? And what else has he told you?”

“About the sorcerer Lopt,” Tom says. “About a boy who put wings on his body and a woman who was once a flower. About the wolves that don’t live in the wood. He says they live in other kinds of places.”

Tom’s mother puts an arm around his shoulder. Her arm is warm, but heavy as lead. “And what isn’t there can’t hurt you, can it? You see, wolves are only a legend.”

Tom stiffens. “Thom can curdle milk,” he points out. “That’s what the shopkeeper says. He can make the grass die. Is that a legend? He can crack the shell of an egg.”

“Yes.” His mother sighs, a drawn-out sound.

“Is Thom going to die because his folk did not take me?”

“Of course not. Did he tell you that?”

“Was he always going to die when the winter was over?”

“No.” His mother’s arm tightens on his shoulder.

“Didn’t you know, though? How could you not know?”

It is the first time he has made his mother cry. He sees the tears move like ice that has melted. He feels cruel. He feels like proving a point. He squirms out from under her arm. “You did know. You did know. You tested him. You made him take hold of iron, and it burned him. How could you?” he asks. “I wanted him to be my brother. But he can’t be. The dead can’t be our kin.”

He runs from the room. He leaves Thom coughing, small white feathers coronating his head. Tom runs from the cottage and slams the door behind him. The night air is calm and cool and wet. Tom sits on the step of the little stone house. He watches the moon make inlets in the clouds’ sediment. The land under them looks lifeless: a flat black sketch of trees and hills. A mess of earth. Dead. The air is so warm that his breath does not frost it.

He thinks about the wolves. Where are they, if—as Thom insists—they’re not in the wood? Somewhere further, in the same far place as Thom’s bird, in that other country? He pictures them: hunting-eyed, light-footed, and lethal. Just a few feet from him the wood begins, and beyond it. . . . He can hear the thrumming of their great paws. He can hear the drum of their heartbeats pounding, a low-down rhythm that he longs to feel in the cage of his chest. Their grave eyes search for him.

He stands. He starts forwards, not sure of himself. He goes towards a point he can dimly sense. Steadily, now, he picks up speed. Above him, the moon sleeps in darkness. He hears birds calling all around him. He listens for the single note he needs, the note he has not heard before, unmelting and solid. I am here, he wants to shout. I am here; I am coming. Take me, take me. Fear shuts his throat and closes his voice. Still, something in him makes a sound. Soon he is running, swift as the wolves. The wood enfolds him, cold and hard, hastening him towards his homecoming.

“Tom, Thom” copyright © 2016 by K. M. Ferebee

Art copyright © 2016 by Rovina Cai