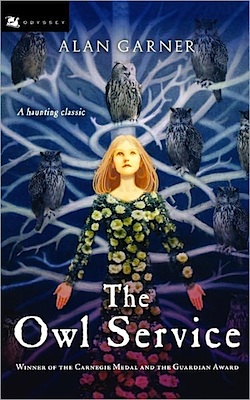

Alan Garner’s The Owl Service is the spookiest book you’re ever likely to read about a set of dishes. It’s also about Welsh nationalism, British class snobbery, the Mabinogion, teenage angst, family secrets, the sixties (it was written in 1967), the Power of the Land, and the broodiest, most sinister housekeeper outside of a Daphne du Maurier novel.

It starts off, not with a bang, but with a scratch. Teenaged Ali, sick in bed in her Welsh country house, complains that there are mice scratching in the attic. Gwyn, the housekeeper’s son, climbs up to investigate, and brings down a set of dishes with a strange pattern on them. Ali is immediately compelled to trace the design on the plates, cut up the tracings, and assemble them into little paper owls—which keep disappearing. The scratching gets louder. Gwyn’s mother, Nancy, becomes unaccountably furious about the dishes. The pattern disappears off the plates, and then they start falling—or being thrown, but no one will admit to throwing them.

Roger, Ali’s stepbrother, finds a huge rock in the valley with a strangely smooth, perfect hole right through it. He tries to photograph it, but it never comes out right. The pebble-dash finish falls off an interior wall, revealing a painting of a woman. Then the painting, like the pattern on the dishes, disappears. The ladies in the shop murmur to each other in Welsh, “She’s coming.” Eccentric old Huw Halfbacon, caretaker of the property, shuffles around the edges of the action, muttering cryptic things like “Mind how you are looking at her,” and “Why do we destroy ourselves?”

And then things get really creepy.

The Owl Service is one of those very British books where the author lets you figure things out for yourself. A lot of the book is bare dialogue: no exposition, no background, just a fly-on-the-wall—or ear-to-the-keyhole—view, so the reader is in the same position as Gwyn and Ali and Roger, trying to understand what’s going on without all the information at hand, and scrambling to make sense of events that make no sense, so that the full, sinister truth comes through the haze only gradually—and is all the scarier for that.

The spare style also lets Garner pack a lot of complexity into a mere 225 pages, without getting bogged down in explanations or analysis. At the heart of the book is the story of Blodeuwedd, a tale in the collection of Welsh mythology known as the Mabinogion, in which the hero Lleu Llaw Gyffes, cursed by his mother so that he can’t take a human wife, contrives to have a woman made out of flowers. When she betrays him with another, he has her turned into an owl.

The three teenaged protagonists, it emerges, are re-enacting the tale of Blodeuwedd. And they’re not the first ones, either: the story has been played out over and over, most recently in their parents’ generation. Throughout the book, there’s a sense of currents gathering to a head, of chickens (or owls) coming home to roost—deadly ancient powers, but also contemporary social and personal ones. Gwyn, Ali, and Roger are all driven by forces and patterns they don’t understand or know how to resist, much of which has to do with their parents.

Ali is a cipher, entirely preoccupied with not upsetting her mother (who is the force behind much of the action—most of the other characters dance around her demands, and fear her disapproval—but never appears in scene). When asked what she wants to do with her life, Ali can only answer with “mummy’s” expectations of her. Ali’s has been nearly drained of selfhood before the book even opens: she’s an empty vessel, vulnerable to the malevolent forces contained in the owl plates.

Ali’s new stepbrother, Roger, comes off as a thoughtless, casually condescending twit, hobbled by his class snobbery and the long-held pain of his mother’s abandonment. But Roger is also a photographer, and when he can overcome his prejudices and his father’s affably condescending view of the world, he’s able to truly see what’s going on around him.

And then there’s Gwyn. Ali and Roger are English, visiting the Welsh valley with their parents on a summer holiday, but for Gwyn the summer’s stay is a homecoming to a place he’s never been: his mother, Nancy, left the valley before he was born, but has never stopped talking about it, so that Gwyn knows the landscape better than the city of Aberystwyth, where he’s grown up and has a place at the prestigious grammar school.

Gwyn is caught between worlds on more than one level: Nancy castigates him for speaking Welsh “like a labourer,” but also threatens to pull him out of school for putting on airs and siding with Ali and Roger over her. Ali and Roger, for their part, treat Gwyn like a friend when it suits them, but Roger, in particular, doesn’t hesitate to pull rank, sometimes nastily, when he feels Gwyn is getting above himself, while Ali saves her haughtiest lady-of-the-manor manner for Nancy, who in turn does her best (along with Ali’s offstage mother) to quash the incipient, semi-covert romance that Ali and Gwyn have going.

By all rights, Gwyn should be the hero of The Owl Service: he’s a working-class underdog with the intelligence and cultural connections to solve the enigma of the plates. But Gwyn is trapped, too: the pain inflicted on him is too deep, and he can’t transcend his justifiable rage to break the curse laid on the three of them.

The Owl Service is full of contradictions: It draws on ancient myth and contemporary social forces in equal part, and twines past and present together. It’s theoretically a children’s book, but assumes a fair bit of sophistication and intelligence of its readers. There’s no overt gore, but it’s scary enough to make a hardened adult (well, this hardened adult) jumpy in dark stairways for weeks after reading it. And even though it’s set in the summer, this is the perfect book to give you the shivers on a Halloween night, or in the dark and windy days of November.

Elisabeth Kushner is a writer and librarian in Vancouver, BC. She’s a little creeped out now by owls. And dishes.