In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

It’s summer reading time again, and there is nothing better to read on a hot day than a pulp adventure story—a tale designed to keep your attention, no matter what distractions you might encounter. “Doc” Smith was a pioneer of the subgenre of the space opera, and with his exuberant and action-filled stories, he made that subgenre an immediate success. The Skylark of Space is his first novel, and is filled with adventures on Earth, in space, and on far-away worlds—enough adventures to fill a whole series packed into a single, slim volume.

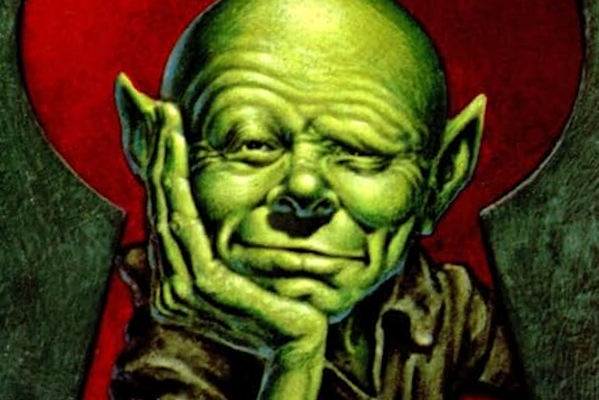

The copy of The Skylark of Space I reviewed is a reissue from Pyramid books, printed in 1968. The book was obviously a success for them, because they’d gone through six printings during the previous decade. The cover is a nicely composed impressionistic painting by Jack Gaughan, who had also illustrated Pyramid’s reprints of Smith’s Lensman series.

Smith reportedly wrote The Skylark of Space in his spare time from 1915 to 1921, and had (uncredited) assistance with the first parts from the wife of a friend, a woman named Lee Hawkins Garby. It first appeared in Amazing Stories magazine in 1928. The story takes many turns in a short number of pages, starting as a tale of invention (in the vein of earlier stories featuring characters like Frank Reade, Jr, and Tom Swift). It then becomes a space adventure (one of the first that attempted to realistically portray an interstellar journey) as the heroes chase kidnappers into the far reaches of space, and must escape the fierce gravity of a dead star. Then the book becomes a planetary adventure (owing more than a little to the influence of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ tales of John Carter of Mars, which had begun appearing in 1911) as the heroes stop at a far-off world for fuel, and are drawn into a local political struggle. The story then takes a detour into a wedding scene that would be right at home in a romance novel, only to return fully to adventure with a gigantic aerial battle featuring futuristic weapons.

The Skylark of Space had three sequels: Skylark Three, which appeared in Amazing Stories in 1930, Skylark of Valeron, which appeared in Astounding in 1934 and 1935, and the later Skylark DuQuesne, which appeared in Worlds of If in 1965.

I’ve previously reviewed Smith’s entire Lensman series, including the prequel books Triplanetary and First Lensman, which covered the founding of the Lensmen and Galactic Patrol; the three adventures of Kimball Kinnison, Galactic Patrol, Gray Lensman, Second Stage Lensmen; and Children of the Lens, which covers the final battle with Boskone and the Eddorians, where the children of Kimball Kinnison and Clarissa MacDougall take center stage. There was an additional book, Masters of the Vortex, set in the same universe as the Lensman series, but with different characters. Once again, as with the Lensman books, I must thank Julie at Fantasy Zone Comics and Used Books for finding this novel for me.

About the Author

Edward Elmer Smith (1890-1965), often referred to as the “Father of Space Opera,” wrote under the pen name E. E. “Doc” Smith. I included a complete biography in my review of Triplanetary. Like many writers from the early 20th century whose copyrights have expired, you can find quite a bit of work by Doc Smith on Project Gutenberg here, including The Skylark of Space.

Scientific Breakthroughs

It was impossible to live at the start of the 20th century without seeing daily life transform before your eyes, especially in cities. Electric trolleys glided down the streets, while elevators allowed the construction of higher buildings. Electric lights replaced gas and oil lamps. Conversations across long distances were made possible by telephones. Telegraphy, no longer confined to wires, could be transmitted by radio. Everywhere, cars and trucks replaced horse-drawn carriages and wagons. Powered tractors replaced mules and oxen in the fields. Indoor plumbing made life more comfortable. Entertainment now included moving pictures and audio recordings on discs called records. Turn-of-the-century inventors like Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Wright Brothers had become heroes, and the public remained eager for news of the latest advances.

And at the same time daily life was transforming, scientists were pushing the boundaries of human knowledge, promising even greater advancements in the future. The work of German theoretical physicist Albert Einstein (1879-1955) shocked the scientific world with new and exciting ideas grounded in solid mathematics. His papers addressed the nature of light, relativity, electromagnetic fields, gravitation, and the relationship between mass and energy. His formula for mass-energy equivalence, E=MC2, suggested that staggering amounts of energy could be released if only scientists and engineers could figure out how to do it. At the same time, he theorized that objects could not move at speeds greater than the speed of light. Einstein’s theories provided a new way of looking at the universe, undermining ideas and assumptions that had been accepted since the days of Sir Isaac Newton. And in 1919, British astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington made observations during a solar eclipse that showed, as Einstein had predicted, gravity could indeed bend light.

Doc Smith was well aware of Einstein’s work, having studied chemical engineering at the same time Einstein was introducing his new theories. His fictional element X, which powered the spaceship Skylark, was certainly inspired by Einstein’s famous formula, E=MC2. At the same time, Smith also mentions Einstein by name even as he became one of the first of many science fiction writers to ignore Einstein’s theoretical speed of light “speed limit,” as it would have made impossible the interstellar voyages he described, and would have significantly reduced the size of his fictional playground.

The Skylark of Space

The book opens in the Washington, DC area, set in an unspecified future with helicopters, supersonic aircraft, and experimental spaceships, but with landmarks still recognizable to the reader. Dick Seaton is a research chemist at the Rare Metals Laboratory, who discovers the mysterious metal “X,” which releases huge amounts of kinetic energy when brought in contact with copper and an electrical current. On his way out, Dick notices that Marc DuQuesne, another chemist, is also still working. Dick hops on his motorcycle and travels up Connecticut Avenue to visit his fiancée, Dorothy Vaneman, who lives in Chevy Chase. [All this local detail owes itself to the fact that, as he was starting the book, Smith himself was working in DC as a chemist at the National Bureau of Standards while doing graduate work at George Washington University.] Dorothy’s family is wealthy, but she thinks Dick is quite a catch—tall, athletic, smart, brave, and not unhandsome in a square-jawed way; a man with a “vivid personality, fierce impetuosity, and indomitable perseverance.”

Dick’s best friend and tennis partner is an engineer who has inherited a huge fortune, M. Reynolds Crane, known to his friends as Martin. Dick finds that the mystery metal only works when exposed to the electrical field generated by a machine DuQuesne runs in his nearby office, a machine Dick knows how to reproduce. When Dick tells Martin about what his recent discoveries, Martin offers to finance Dick’s further research, but they need a way to legally get the X sample out of the government lab. So Dick puts it into a bottle for the regular auction that the lab uses to dispose of surplus material, the two of them purchase it, and Dick quits his government job.

DuQuesne, however, has seen what the two friends are doing, and is the first character in the book to identify exactly what has happened: Seaton has discovered the secret of total conversion of mass into energy. And DuQuesne and his associates, Brookings and Chambers, want that secret for themselves. DuQuesne, whose nickname is “Blackie,” is described as having black hair, heavy black brows that connect over his nose, and a thick black beard that shows even after a close shave (dark hair was often used in the pulps of the day to indicate a sinister nature). Through his actions, we quickly see that DuQuesne is not just an ordinary villain; he is a rather extraordinary character, brilliant, competent, honest, but at the same time utterly amoral. He knows that he and his partners must steal the material Seaton removed from the laboratory, and even coldly suggests that murdering Seaton would make their work easier.

Dick becomes utterly engaged in his new project, and Martin conspires with Dorothy to pry him away from the lab to ensure he gets rest and proper meals. Meanwhile, Brookings and Chambers steal some of the X material, and attempt to have minions experiment with it, but blow up an entire town in West Virginia when the experiments go wrong. They come crawling back to DuQuesne, putting him in charge of their future efforts with what remains of the X material. Meanwhile, Dick develops a rocket pack powered by the X material, and nearly meets his end zipping around in the sky. He and Martin decide to build a spaceship, the Skylark. They also invent some other devices, including an “object compass,” which can indicate the direction to a special bead no matter what the distance, and also “X-plosive” bullets that have tremendous destructive power (did I mention the hyper-competent Dick also happens to be a champion pistol marksman?). DuQuesne leads a burglary and acquires more of the X material, killing two Crane employees in the process, but still cannot find all of it. He also manages to steal plans to their inventions. Dick and Martin, however, quickly figure out what is happening and who is behind it.

Brookings, Chambers, and DuQuesne start building their own spaceship based on Dick and Martin’s plans, and try to sabotage the Skylark construction by supplying them with substandard steel. But Dick and Martin start construction of another spaceship in secret using their own more reliable suppliers. Soon both organizations have a working spaceship powered by the X material. Dick makes sure Dorothy has one of their tracking beads, worried about possible kidnapping. And his fears are borne out when DuQuesne uses his spaceship to kidnap Dorothy. During her struggles to escape, the ship is accidentally launched into space at full speed, tearing its way through space, the acceleration rendering its crew unconscious. Dick and Martin, using their object compass, are stunned to find that the spaceship is already halfway out of the solar system, moving at the speed of light. When Dick says that nothing can move at that speed, Martin replies that Einstein’s theory is still just a theory. It takes them two days to collect enough copper to power the Skylark and fully stock it with provisions, and by the time they are ready to take off, the object compass tells them Dorothy is 235 lightyears away.

On DuQuesne’s ship, after 48 hours of brutal acceleration, the fuel is consumed, and the occupants awaken. DuQuesne realizes what has happened, reveals additional fuel that was not in the engine, and begins to plan a voyage home. Dorothy meets another captive, the beautiful Margaret Spencer, former secretary to Brookings, who had taken the position to uncover dirt on the man who had ruined her father’s business. One of the crewmembers, Perkins, panics and becomes a problem, and DuQuesne guns him down in cold blood. And then they find they are caught in the gravitational field of a “dead star,” an object that sounds like what we would now call a black hole.

But just as things look hopeless, Dick and Martin arrive on Skylark to rescue them, although escaping the dead star uses most of their fuel as well. DuQuesne promises not to interfere or try to escape in a way that would put the others at risk—and the dastardly scoundrel turns out to be true to his word. The adventurers land on a planet looking for copper to use as fuel, only to find the world rich with element X. Then they land on a planet that owes a lot to the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs. It is inhabited by green but attractive men and women who wear very little clothing, and happen to have just invented a knowledge-transferring machine that allows Dick to communicate with them. Their new friends are royalty (as are many strangers in Burroughs stories), and need help to fight their enemies. As the book barrels to a close, there are romances, strange marvels, and massive airborne battles—events I will not summarize in detail to avoid spoiling the fun.

Final Thoughts

The Skylark of Space is anything but high literature, and its characters and situations lack any semblance of nuance. But the story is compelling, and the adventures keep you turning pages right up to the end. I enjoy Smith’s Lensman books, but this one is even more fun, and is a nice, self-contained tale.

I’d like to hear the impressions of others who have read the book. And as always, if you have any other pulp adventures you want to discuss, the floor is open.

I did enjoy reading the Skylark books as a kid, though I personally prefer the Lensman books–those I’ll come back to occasionally, whereas these I won’t.

It’s possibly worth mentioning that Marc DuQuesne makes a return in Ryk Spoor’s Grand Central Arena books. Kind of, anyway, though I’m unclear on the details. I have the first volume but it’s on my TBR pile.

These books were actualy the first non-comics books I read on my own, at the age of 8. I read their synopsis about giant spaceships and colossal battles in a magazine, and was immediately captivated and asked my parents to order those books asap.

In the following year I re-read them at least 4-5 times.

Even then, as absolutely fascinated I was by the spectacle of the giant battles, wondrous inventions and super-evil villains, some things gave me pause.

Now, as an adult, watching back, I can’t unsee the terrible racial attitudes of the day (the books actually kinda advocate *eugenics*, even without talking about more modern concerns like representation or equality or such things), and a certain approach to genocide as the solution for any conflict. The protagonist from time to time ponder and suffer on the choice for a whole 5 minutes before going with it while explaining why it’s absolutely unavoidable.

Genocide that scales quite quickly from nations in the first volume up to a full galaxy in the last.

Luckily, after this first dip I sampled a much wider range of SF and mainstream narrative and once I got over the general lack of gigantic space battles described in purple prose, more modern SF helped me get a wider comprehension of moral issues…

It’s definitely a book of its time, but Skylark is still fun, and I occasionally re-read it. Yes, there are some elements that haven’t stood the test of time very well, but of what literary work is that not true?

(Minor note: I seem to recall at least one edition of Skylark Three that advertised itself as the third volume of the sequence, when in fact it’s the second. Be wary of numbers in your titles.

I enjoy these as well. The first book is probably the best one. The stakes scale enormously over time, as you would expect from Doc Smith.

Just like @2 Fizz, as an adult reader I find I have to turn a blind eye to the eugenics, genocide, and idealized, totalitarian government, but the adventure bits in between are inventive and tremendous fun.

One of the things that I get a kick out of now is the blend of mechanical and “force” based technology. The idea that an advanced machine would need banks and banks of pedals, keys and dials to operate seems quaint now, while at the same time, the telepresence allowed by those machines are not fully realized yet today, a hundred years later.

I tried to find the “official” publisher ebook versions recently, but because these are in the public domain its pretty difficult to figure out which ones are based on the print novels. Now that I think of it, I’d love to see the difference between the original magazine versions versus later hardcover and paperback editions… (did “Gharlane of Eddore” ever take that on? I can’t find anything on the internet so far)

As others have said, Doc Smith books are a product of their time and have to be read with that in mind. Saying that, if you can accept certain elements that are problematic from a 21st century viewpoint they are great fun. Lots of romance and fights, space battles and exciting stories. The good guys are really good, the ladies are actually quite competent even if they do fall into the “damsel in distress” at times, and the bad guys are really bad. DuQuesne is a fascinating character in that he is a match for the two protagonists, but is absolutely ruthless. Even then he has a strong moral code, it’s just not the same as ours. He will lie and cheat and scheme and murder to gain his objectives, but he keeps his word and only resorts to other less savoury means when there is no other way. He’s also happy to work for the common good if it’s to his advantage and will put his whole self into the endeavour. In a later book he even calls on our heroes for help when he discovers a threat he can’t handle. Of course it’s selfish, it’s interfering with his own plans….

What I find interesting is that as the antagonist he doesn’t fall into the trap that most modern stories do. For some reason modern writers always feel the antagonist has to turn on the heroes when it’s to their advantage to keep their word. We all love a bad guy, but they all make utterly stupid decisions so the good guys can win. Usually it’s a betrayal at the worst possible moment, or breaking their word when it seems advantageous, when as DuQuesne shows, keeping your word and not actually switching sides at the last minute always works out better.

When Skylark was first published in Amazing Stories (August 1928), the issue also included the prose adventure of Anthony “Buck” Rogers in the 25th century. That became a comic strip in Jan. ’29, and sent its hero into space for the first time in Jan. ’30. Tor readers probably know that, but it’s worth mentioning!

The eugenics are creepy– the green people are what you might get if the Nazis were right and not kidding themselves. The green people have bred themselves into physical and moral superiority. Conveniently, the physical superiority is for a planet with lower gravity than earth, so the earth people are stronger anyway.

By some coincidence, the folks the good green people are fighting are a darker shade of green.

Another angle is theosophy, a style of occultism which turns up in other authors, too, notably Heinlein and Clarke. One example is the ideal of eternal marriage.

I love both this and Lensman (Lensman better for many reasons).

With regards to Nancy’s comment I note that in this series if you’re humanoid you’re good and if you’re a Fenachrone (space nazis?) or worse a Chloron you are presumed to be evil.

In Lensman there are many non-humanoid good guys and we are explicitly told by a (human) Lensman on several occasions that he looked past the physical shape and saw that “this was a MAN” (in a positive sense).

@2 haven’t read any but the first of the Skylark books, but it sounds like the later ones are more problematic than the first.

@5 I think DuQuesne ended up being a more interesting character than the heroes!

@6 It is Amazing to find that both Buck Rogers and the Skylark series started in the same issue of the magazine.

@9. Like you I have loved the “Doc” Smith books for years. DuQuesne became one of the most popular SF villains back when these stories first appeared in the pulps.

My library had 3 of Doc’s books — Skylark 3, Spacehounds of the IPC and Triplanetary. I read either S3 or SHIPC first. TRP was lost for awhile and then suddenly reappeared. I found both Skylark 3 and Skylark of Valeron very enjoyable. SofV involves the 4th dimension and I went crazy trying to figure out a direction perpendicular to our 3 dimensions. Skylark DuQuesne is OK but is the low man on the totem pole.

I went crazy trying to find SofS after I read S3. It was several years before I discovered that SofS had been published in paperback by Pyramid Books. I mail ordered it directly from Pyramid and it took over 2 months before it arrived! I died a little every day when the mailman came.

I didn’t learn about the Lensman series until several years later.

Just like a lot of others out there I have loved Skylark and Lensmen for years. And since you mentioned Burroughs, his John Carter of Mars were read first, followed by Skylark and Lensmen. I have read and have purchased them all, in paperback. Of all the ‘space opera’, Lensmen is my favorite. And even though Asimov was chosen, my favorite is still those by Doc Smith, over Asimov’s Foundation novels., as the best ever written!

Supersonic airplanes? Where? Crane and Seaton take a biplane to test the x-plosive pistol ammunition, as I remember it. And the word doesn’t occur in the Project Gutenberg ebook.

Mrs. Garby’s contributions were credited in the magazine publication and the early book publications. The text was considerably revised for paperback publication, and her name was dropped at that time. (Comparing those versions is interesting, much bigger differences than with most books.)

I think the last book of the Skylark series, Skylark Duquesne, is perhaps Smith’s best work. Duquesne actually exhibits some character development. Although at the end…I imagine he and Hunky are heading off for a major tragedy. He appears to have failed to notice the problem that brought the Eddorians low — bad news does not flow upwards in authoritarian organizations, leading to the people at the top making huge mistakes.

I suppose it could be viewed as a genocide problem. I think of it slightly differently, as a biological determinism problem — the Chlorans are just inherently evil, as are the Fenachrone. Apparently the Llurdi aren’t. Mind you, that Chloran galaxy just ready to leap to many other galaxies was a valid existential problem probably not amenable to lesser solutions.

“Skylark of Space” was revised a couple of times during its long run to update the technology (at least from 1921 to the 1960s) and play down some of the problematic racial aspects. I believe the Gutenberg edition has the original text. The Pyramid paperback reprint has the latest version.

I’ve read the Skylark and Lensmen series multiple times. I find it interesting that the ultimate solution in both is the total extermination of the enemy species.

Perhaps interesting is not the best word.

Well, Seaton’s party does move the Chloran planet that attacked Valeron back to it’s home solar system rather than destroying it. The Llurdi continue to share solar systems with the Jelmi, though on a more equal basis. Storm Cloud manages to bring something like peace between Dhil and Lune. First Lensman Samms sends the Petrinos home with their fleet intact after they attack Earth. The Subspace Explorers make peaceful contact with the Justiciate (or at least the psiontists there) despite the destructive interactions of their earlier encounters. Etc.

So killing everybody isn’t the only way he knows to resolve conflicts. Still, the bigger conflicts end up being resolved that way fairly often.

It’s stated that Eddorians just “can’t” be any other way than the way they are, nor can the Fenechrone. That doesn’t really match any actual experience with races or cultures, but we’ve only had contact with one race, the human race. Behavior at that level, in us, isn’t much controlled by genetics.

@12 It appears the editors did some updating in the paperback edition of Skylark of Space that I read. There was indeed mention of supersonic aircraft, and instead of a biplane, the heroes fly a helicopter to test the X pistol. So instead of Smith being ahead of his time, someone was tweaking the story after the fact.

Another reason to love the writers and writing at tor.com–a shout out to E. E. Smith! Spacehounds of IPC lives green in my memory of my youth just as what you describe–a fun, fast-moving pulp space opera. The hyper-competent characters in this book are many, even interplanetary. But the stand out is Steve-from creating a bow to mining a comet, Steve triumphs over all.

@15 The “editor” was Doc himself. He said on numerous occasions that the Pyramid version was his preferred version.

@16 Spacehounds of the IPC was Doc’s favorite book. In fact he considered it his best SF novel.