In the same world as Everfair, a brutal king plagued by visions of the Black people he slaughtered in Congo attempts to destroy the spirits haunting him using an inventor’s powerful but unproven machine . . .

Author’s note: This story was difficult for me to write, and it may be difficult for you to read. Because it’s told from the viewpoint of Leopold II of Belgium, a notorious creep, it includes instances of antisemitism, misogyny, and racist name-calling. In fact, the n-word appears twice within this story’s first paragraphs. Please shield and/or heal yourself from the nasty effects of that sort of hatefulness however you can.

Versions of this story have appeared in Nightmare Magazine; The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2017 published by Mariner Books; Making History: Classic Alternate History Stories published by New Word City; and the anthology Our Fruiting Bodies published by Aqueduct Press.

“A chemical process for converting natural rubber or related polymers into more durable materials via the addition of sulfur or equivalent curatives or accelerators. These additives modify the polymer by forming cross-links (bridges) between individual polymer chains.”

Brussels, 1898

Another black. A mere illusion, Leopold knew, but he flinched out of the half-naked nigger’s path anyway.

Of course Marie Henriette noticed when he did so. The quick little taps of the queen’s high-heeled slippers echoed faster off the polished floor as she hastened to draw even with him. “My dearest—Sire—”

Leopold stopped, forcing his entire retinue to stop with him. “What do you wish, my wife?” He refused to turn around. Once he had done so, and had seen then no sign of the savage who’d just the moment before brushed past him—through him—with a fixed and insolent stare.

Not much longer till he would be rid of his ghosts for good.

The queen reached for his sleeve but held her hand back to hover above the gold-embroidered cuff. “Are you quite sure you need to do this? Are you sufficiently well?”

He had wondered whether to tell her about his appointment with Travert. In the end he hadn’t, dreading an increase in court gossip. “The Museum of the Congo is important to my legacy. We will not be late for the dedication, Marie,” he objected in his usual mild tone. She said nothing further, and he resumed his progress down the passage to the palace’s exit.

Outside, the sky’s silver overcast was brighter than any light Leopold had experienced in more than a month. Perhaps he ought not to have confined himself so long. It didn’t seem to have decreased the apparitions. Nigger visions had plagued him night and day. Sometimes they held up their bleeding, handless arms accusingly, shaking them in his face. Gore fountained and dripped from their wounds, yet the carpets over which they passed remained stainless. Illusion only, but it would be a relief to be done with them.

He settled himself comfortably in the royal steam barouche. Marie Henriette hesitated a moment before climbing in beside him. Her fondness for horses was well known, but Leopold had explained patiently the need to show support for the manufacture of rubber and its essential role in modern mechanization. Absently he patted the reinforced fabric of the seat cushion: water repellent, elastically resilient, warm to the touch as—

Involuntarily he jerked away. He met the eyes of Driessen, his personal physician, taking the opposite seat. Poorly concealed concern peered back at him. Deliberately the king set his hand back on the spot from which he’d removed it. When he could turn his head casually, as if taking in a passing prospect, he saw nothing more than a vague cloudiness roiling the air of the steam barouche’s interior. Arriving at the site of the museum and disembarking from the machine, he left it behind.

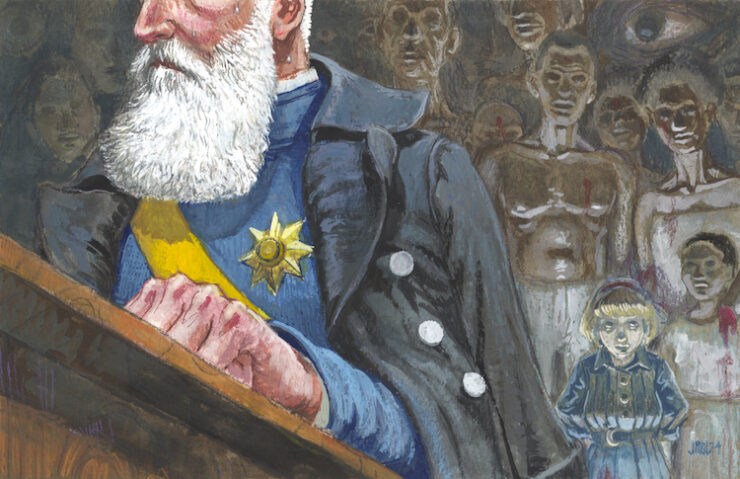

The quiet crunch of the gravel walk comforted him. Climbing granite steps to the half-circle portico where he would speak, Leopold threw back his shoulders and gave Driessen and Marie Henriette what he hoped was a reassuring smile. Approaching the podium, he pulled his memorandum pad from his military-style jacket’s inner pocket and opened it to the relevant page. He looked out at an audience abruptly filled with hundreds of weeping black faces and with a cry let it fall to the ground.

A stifled gasp came from his queen, counterpoint to the sobs only he could hear. Then the pad was set into his nerveless hand, his fingers bent to curl around and hold it. Driessen. The physician was asking him something. Leopold nodded—he hadn’t heard the question clearly, but assumed it concerned his welfare. He would go on with his speech. Noblesse oblige.

“Learned and generous contributors to our great enterprise,” he began, “the enlightenment of the savage inhabitants of heathen Africa: it is with joy I invite you today to enter with me the magnificent edifice created to shelter the fruits of our noble laboring.” Continuation became easier with every word. With his mental faculties fully exercised by the demands of his oratory, Leopold’s visions faded till they were virtually invisible. To convince himself those faint specters were truly immaterial, he had only to remind himself that mere minutes remained now till the appointment.

Travert was sallow-skinned and pitiably slight—also balding and bespectacled. Perhaps a clandestine Israelite? Quite likely. They were everywhere, and for the most part harmless. This one waited on the king in one of the museum’s private rooms, which Leopold found rather plain. Undistinguished paneling, ugly gas lamps affixed to it such as he would never choose. The smell of some crude cleaning compound troubled his nostrils.

The Jew bowed deeply. “Majesty,” he began, “I am mindful of the great favor you do me in granting me permission to share with you my new invention. The variable pressure ethereo-vibrative condenser displays the most interesting principles discovered to date in the field to which I’ve devoted so much study, so much—”

Mary Henriette wrinkled her pretty brow. “But were you not hired to oversee the care of the inhabitants of the museum’s model village?” In the confusion following the king’s public appearance she had shed her attendants and somehow insinuated herself into the room, taking a seat at Leopold’s side. “I’m afraid I see no connection between that and your—elusively gyrating—whatever you may say.” Her white shoulders shrugged off their covering of lace. “The king is busy. He has been ill, overwrought—”

Driessen coughed meaningfully into his fist.

“My queen,” said Leopold, “this very illness is the cause of my curiosity regarding Dr. Travert’s investigations. They may perhaps be of help in curing me—” He swept one shapely hand in the little Hebrew’s direction. “—by means he was just about to explain.”

“Yes, of course.” The bald head ducked in acknowledgement. “You see, my condenser renders palpable the vaporous emanations of the spirit world so that they may be, ah, dealt with in a corporeal manner: jailed, burnt, buried, dissected—”

“It is due to evil spirits you’ve gone on so poorly? You never told me!” Marie Henriette twisted and leaned toward the king. Her breasts huddled forward, threatening to spill over the loose confines of her satin bodice. “Let me bring my confessor to you—tonight, after supper!”

“Why?” demanded Driessen.

Leopold dragged his eyes to where Driessen rocked heel to toe, toe to heel. His brusqueness was to be expected. The royal physician tolerated this latest attempt at reconciliation with Marie Henriette, but made no secret of his cynicism in regard to her.

“Why?” the queen retorted. “To disavow the guilty sorrows such things find attractive. You will feel much better, dearest, once you’ve relinquished your burden of sin.”

But Leopold had done nothing wrong. The casualties in the Congo were necessary to the extraction of its wealth. He looked at Marie Henriette as blandly as possible. With age her fascination was shrinking. “Perhaps,” he temporized. “However, first we’ll try Travert’s method.” It seemed more certain, more scientific.

Though there was one point about which he worried. “You have tested the procedure?” he asked.

“Naturally. With the access to your African subjects you have so kindly granted I was well able. In fact, I have prepared a demonstration for you to view before your own condensation. It only remains for me to outline for you the particulars of the apparatus’s operation and we’ll get started.”

It required the full force of Driessen’s insistence to make the self-aggrandizing Jew realize he could deliver this outline while simultaneously enacting his far more germane demonstration.

Of Leopold’s personal guard only Gagnon, its head, had entered the room with him. In the crowded corridor they joined the rest of the detachment, descending thence via unfinished steps to a basement, where the odor of the cleaning compound threatened to overwhelm him, though he couldn’t determine if it affected anyone else. After they had negotiated several jogs and branchings, Travert called a halt to the procession and unlocked a large wooden door in the passageway’s right-hand wall.

The space they entered held charcoal-colored benches, one covered in a jumble of equipment: glass tubes, snakelike hoses, metal fixtures glittering in the scanty light falling from small windows near the room’s bare rafters. Its far end was obscured by a brown velvet curtain. Travert drew that aside to reveal a lectern and, looming behind it, a tall, narrow booth. Or a cage—that might be a better word for it, since bars of brass stretched from its raised floor to a height crowned with a barrel-like tank and some geared apparatuses he couldn’t quite descry.

Travert swung the cage’s barred door open as they approached. A pale face seemed to coalesce behind it, to shiver and deform itself. Then Leopold realized this was but his own reflection. The bars were backed with smooth panes of leaded crystal, as its inventor explained. At length. They helped to hold in certain vibrations that it was desirable to contain in order to concretize the evanescent portion of the targeted phenomenon. Certain chemicals in combination with steam-driven increases in atmospheric pressure wrought bridging chains of causality between the captive spiritual energy’s various potential states and resulted in manifestations tangible to all.

Before the fumes of whatever nauseating substance was so prevalent here bested his control completely, a scuffle at the room’s entrance ensued. “Ah! Here is my favorite now—” Meeting a couple of men halfway back along the room’s length, the Hebrew urged them onward. Between the pair of them the men propelled a struggling nigger woman who slapped and kicked them ineffectually, screeching at them an endless stream of what were doubtless heathen maledictions. Reaching the cage they flung her inside. Like a wild beast she leapt snarling to her feet and charged the door—but Travert speedily shut and secured it.

Her stink fought strenuously against the chemical scent overlaying everything else. Raising to his nose a cologne-soaked handkerchief he hoped would block these disagreeable odors, Leopold leaned forward to scrutinize the lectern to which Travert now advanced. It had been modified by the addition of a peculiar wheel like a gleaming halo, and several switches and levers. Manipulating one of these, the doctor set off a low, heavy-sounding hum. The king looked an inquiry.

“Power from that rank of batteries to your right”—Travert pointed to a row of crates formed of some black, dull-surfaced metal—“primes the mechanism while the generators build up sufficient steam.” The nigger wench had ceased her wailing imprecations and sunk to lie sullenly on the cage’s bottom. “Much as when the heat and pressure employed in vulcanization collects prior to . . .” Ensorcelled by his own arcane activities, Travert allowed the explanation to trail away. Frowning, he slid a yellow-enameled lever down to a position approximating that of a neighboring blue one.

“Go on,” Leopold commanded. His stern tone woke Travert from his trance.

“Whatever manifestations Fifine accords us—”

“‘Fifine’?”

The doctor’s sallow cheeks blushed like a maiden’s. “My name for the subject—I must call her something, and her African name is far too outlandish.”

With the nipples of her flat dugs aimed at the cage floor like dusky arrowheads, the drab resembled no Fifine Leopold had ever known. And he had known a few. But let the man indulge his fancy. “Very well. What would you tell us about the manifestations of this ‘Fifine’?”

“The condenser will render them visible, palpable, subject to study and measurement. From mere ectoplasmic excrescences they will be focused and solidified—”

“Yes, yes.” The soft hum stealing out of the rafters had been growing steadily louder. Leopold pitched his invitation above it. “Driessen, if you will do the honors?” The royal physician laid his hand over the Israelite’s and gave the lectern’s wheel a swift spin. It connected to the apparatus above the cage by a series of looping belts and toothed cogs, all of which now began to turn. They did not cease to do so when the wheel did.

Brushing his hands together as if to remove invisible soil from his fingers, Driessen released his hold, and Travert deserted his lectern for a new post directly before the cage. He addressed its occupant. “Fifine? You are prepared for a demonstration?”

Leopold was taken aback to hear a reply in French. “How can you ask such a stupid question?” He looked to make sure: yes, it was the nigger herself who answered! “The harm you have caused me with your condenser has no cure. Haven’t I told you? Yet you persist in destroying all that remains to me of those I love.”

Travert’s cheeks reddened again. “Fifine! Must I gag you? I haven’t touched a hair upon your head! What will His Majesty think?” He turned an embarrassed countenance to the king.

“I think that you had better get on with things.”

The doctor returned hurriedly to the lectern, ignoring the nigger woman’s yammering—as he ought to have done from the first. A red lever was moved to a position paralleling the blue and yellow. Clouds of fog descended from the cage’s ceiling, grey and black. The terrible odor increased, forcing Leopold to retreat to lean upon a bench a few feet back. There was naught to see nearer anyway: coiling smokes filled the cage and obscured its contents.

For long moments nothing more happened. Then the laboring noise of the condenser’s growling motors ground slowly down to silence.

Gradually the clouds within the cage cleared, disclosing the slumped form of the black on its still-murky bottom. And—other forms? Smaller shapes were scattered around the large one. Did they stir? Yes! Leopold drew closer. A quiet chirping rewarded him. Ghostly birds hopped and fluttered through the dissipating mist. Like dusty sparrows on some plebian roadway they pecked at their fellow prisoner, soon rousing her.

An odd expression came over the woman’s face. On a white Leopold would have taken it for a compound of regret and delight. Of course the lower orders were incapable of such complicated mixtures of emotions. If he hadn’t known this for a fact, however, he would have been hard pressed not to attribute such feelings to her as she petted the hopping, shadow-tinted birds with the most delicate of touches. Under the machine’s noise and the twittering the bird things emitted he caught her whispered murmurs and cooed nonsense.

The doctor approached him. “The flock has thinned considerably since our first experiment.”

“Indeed?” Leopold imagined the cage busy with the dull-plumed little birds. “What became of them?”

A pursing of his lips made obvious Travert’s Oriental ancestry. “They furnished us with material for several informative experiments. But have you comprehended the procedure so far? The carbon and other additives being linked to the interacting surface of the manifestations and showing us thereby their outlines—”

Would the man never cease droning on? Stifling his exasperation, Leopold glanced significantly toward Driessen, who stepped forward and placed a silencing finger on the Jew’s thick lips. “Enough!”

A moment Travert’s jaw dropped and hung open; a moment his ungloved hands twitched in the barely breathable air. But then, not being mad, he composed himself and motioned the nigger’s escorts to come with him to open up the cage.

Reluctant as she had appeared to enter the brass and crystal enclosure, “Fifine” made yet more difficulty about leaving it. One of the doctor’s assistants gripped her wooly head, even bringing himself to insert his fingers in her gaping nostrils; the other secured her kicking feet. But they had to call for a third man to grasp her wildly flailing arms before they managed to eject her from the room.

Leopold’s eyes followed the disturbance toward the door, but came to rest on his queen. The sight of her, almost as green and pale as the walls against which she sought refuge, moved him to hold out a welcoming hand. She ran quickly to catch it up. “I’m so sorry you’ve been put through such an ordeal, Marie,” he apologized. “You need not remain longer if it pains you.”

“I could not desert you!” Her refusal to leave gratified the king. He caressed her plump wrist, intending to raise it to his lips.

WHACK!

Leopold jumped involuntarily. The doctor reacted to his stare with a guilty shift of his eyes, hefting up the meter stick he carried. “My apologies. I missed my mark,” said Travert. “For your convenience it will naturally be best to clear the condenser’s apparatus immediately, and as we’ve conducted plenty of trials already with this sort of specimen—” He gave a Levantine hunch of his shoulders and returned to clubbing down the dingy birds shut with him inside the cage. Only four remained active, but they gave the Jew an inordinate amount of trouble, their cries loud and frantic as they flew erratically about. The flat crack of the stick meeting bare metal sounded again and again.

Travert’s three assistants reappeared and soon dispatched the last of the vermin in a flurry of high-pitched little shrieks. The Jew then had them shovel out the corpse-like refuse.

At last Travert indicated with a bow that the condenser’s cage was ready for Leopold to enter. Driessen walked in before him, examining the situation. “His majesty will require a chair,” the royal physician declared.

Seated upon a velvet-covered, spindle-legged stool, Leopold found the unpleasant odor increased. The cage’s door shut, and the heliotrope in which he’d drenched his handkerchief barely compensated for the intensified smell, which filled the surroundings like a half-live thing. After an interval of building noise above his head, he heard a subtle hiss and looked up to see the dark, descending smoke.

Would it affect him, a European, as it had the quasi-animal “Fifine”?

Rotting greyness clogged his eyes, his nose, and when he tried breathing through it, his mouth. Stoic determination fled. The king gagged and fainted.

A cool breeze woke him. Refreshed, he opened his stinging eyes to gaze upon a little garden planted with tropical trees, bushes, and flowers—doubtless the produce of his Congolese holdings. He had designed several such gardens to fill the museum’s courtyards. One of Gagnon’s men must have carried him here so he’d more easily revive. Certainly the fresh air was an improvement, and the scene that met his eyes far more pleasing than that of the stuffy cellar: fat stems held nodding blooms of cinnabar, violet, and gold, and broad leaves, some veined in white or pink, quivered softly on all sides.

It was proper that the guard, having brought him here, had departed, but where were Driessen and the queen? Was he actually alone? How odd. No—through the foliage Leopold glimpsed a young girl approaching him. Comely enough, though her final steps showed her to be clad in a boy’s shirt and trousers.

“Hello. I’m Lily.” A frank, open expression sat with habitual ease upon her healthful features.

Meaning to announce his royal status in a charming yet authoritative manner, Leopold was suddenly rendered voiceless: the girl’s left leg had that second become a pulpy mess of gore and bone. His throat filled with vomit. He choked it down.

“Ah. My injury disturbs you. You haven’t yet had time to get used to it as I have.” The girl gazed ruefully down at her shattered limb. “Your soldiers shot me last October, during our rescue of King Mwenda, and I died that very night. Nearly six months now, isn’t it?”

Leopold gaped at her. He must have looked exceedingly foolish. Chief Mwenda had led a rebellion against the king’s Public Forces. “You are a—a gh-gh-ghost?”

“Isn’t it obvious?” She flicked a careless hand at the red ruin on which she stood. Impossibly.

A ghost, then. But she was not black—an English Miss, to judge by her accent. A white girl—though perhaps not of Europe? Of Everfair, then, the Fabians’ damned infestation of a colony wreaked on lands they’d bought of him? Yes! Had not Minister Vandelaar told him recently of an attempt by those traitors to aid that black brute’s escape? Though temporarily successful, it had, so the intelligence minister said, cost the rebels of Everfair an important casualty.

Which would be this Lily. Lily Albin, as he recalled now. Daughter of the rabble’s leader, a hoyden suffragette.

Was this to be his sole manifestation?

Where were the sooty multitudes who had haunted him all this while, whose silent groans had pestered him so, bidding fair to drive him mad? As he understood Travert’s method, if the nigger ghosts could not be condensed, they could not be got rid of.

The girl answered as if he’d asked his questions aloud. “Do you think you have any control of who you see?” Her eyes whitened like a blind woman’s. “Or how? Or what?”

Rising from beneath the thin scent of the garden’s flowers, the mephitic cleaning compound’s fumes assaulted him anew. They couldn’t have traveled here from the cellar—he must still be inside it! In the condenser’s cage! How could he have forgotten? The stool he sat on was the same. The rest of what he experienced, the vegetation and the building heat, might be nothing more than an hypnotic nightmare induced by that quack Travert.

He swung his head from side to side, peering around the foliage, looking for the Jew or one of his assistants. Shouldn’t they be waiting nearby?

The girl Lily laughed. The ivory hollow beneath her neck flexed like the foaming pool below a waterfall. “You thought the condenser would cure you?” She subsided to a low chortle. “Of course you did. Why else submit? But whatever gave you the idea?”

He should humor her. He wiped away a trickle of sweat. His attendants must return soon—or, no, he was asleep and would soon wake. How long had the nigger “Fifine” lain prostrate? Despite his more sensitive and highly evolved nervous system, he surely ought to begin to recover momentarily. He stood up from the stool and thrust aside some obscuring boughs to get a better look around. His entourage remained absent, but a flickering motion just out of sight impelled him forward. A manlike shape, glistening in the patchy sunlight as if made of ebony. He walked swiftly toward it for several meters.

Then he stopped.

The garden was not small. The museum’s walls did not enclose it. Nothing did. It was a jungle, not a garden.

Why should this frighten him? Dreams could not hurt or kill him. He would not die.

He reversed his path. Now that he was thinking clearly he realized how stupid he’d been to leave the spot where he first found himself. But when he returned it was to see his seat occupied by the dead girl. “I hope you don’t mind? Easier for me than standing.” With smiling casualness she gestured again at her mangled leg.

Ever the gentleman, Leopold refrained from pressing the claim of his superior birth, though the oppressive warmth and the burgeoning smell of the cleaning compound threatened to overwhelm his senses. He put a hand out to halt the world’s swaying and flinched back from the pricking thorns of the branch he’d grasped. He stared in pain and surprise at the blood welling quickly out of many little wounds—his sacred essence! Wrapping his handkerchief around the cuts seemed to do no good; if anything they bled more fiercely than before, specks of scarlet growing wider, wetter, joining to make of it one sopping, crimson banner.

His Russian cousins could perish as a result of such small injuries. And he?

“Oh, I don’t believe you’re done for just yet.” The ghost Lily gazed up at him with blank eyes. “Though with so much blood you’ll be creating many more _____, of greater power. As you will come to find.”

He didn’t understand the word she had used. “I beg your pardon? More—more—what do you say?”

“_____!” Again she gave her chilling laugh. “The ones you expected to find here instead of me.”

The nigger spirits, she meant. He thought she nodded. “Those spawned so far wait with your retinue for you to waken.”

The stink and heat and dizzying sway worsened. He fell to his knees. He felt the hot blood soak through his trousers where they sank into its spreading pool. He must rouse himself out of this trance now, then let the Jew doctor’s assistants deal with executing whatever this abominable treatment had brought forth. Leopold strove with all his might to wake.

“But no one will be able to do anything to your _____, to even touch them. Except for you.”

He was lying on his side. He tried to sit up. What did she mean? “Fifine’s” dirty-looking little birds had been easily dispatched.

“Ah, but have you the sort of relationship with your dead that she does?” The ghost girl seemed to have lain down next to him, for her face was but centimeters away. “No. You do not.”

With those words her white face sprang suddenly nearer—or did it swell with decay? Tightening like a mask, it slipped rapidly to one side and receded on a tide of blackness. Then that tide, too, receded.

His eyes were open. Grey clouds parted to reveal the cage’s tarnished ceiling. Leopold lay now on his back, looking heavenward. He lifted his wounded hand: no sign of injury remained.

“Your Majesty!” The Jew rushed to his side, Gagnon and Marie Henriette right behind him. The dream was over.

Or was it? A haze of darkness formed above them. Gradually it lowered and interposed itself between the king and his attendants, forming at last into the likeness of a group of soot-skinned savages. Which, as before, no one else appeared to see. Which, it seemed obvious now, no one else ever would.

There were three of them: a handless young buck; a withered old granny with her head staved in; a child with only stumps for legs and no feet. They closed around him, clumsily lifting him from the cage’s floor. Leopold’s scalp crept as he felt the soft resilience of their nonexistent flesh. He retched convulsively and shoved away the tiny hands, the yielding arms. These newly palpable horrors.

All his life Leopold had known himself to be as brave and strong as he was good and handsome. All his life till now.

“Sire!” The oily voice of Travert intruded itself into the king’s thoughts.

“My dearest!” The queen, too, sought his attention.

Leopold opened eyes he hadn’t realized he’d shut. The ghosts were defiantly visible. But still, always, only to him. Ignoring the phantoms’ reproachful gazes, he leaned on the arms his supporters offered, letting them lead him out of the condenser. As if the weeping niggers reaching to interrupt his passage with their weak and truncated limbs weren’t present. As if they made no actual contact. As if the king didn’t understand himself doomed till death to feel, over and over, the hideous warmth of their touch.

“Vulcanization” copyright © 2024 by Nisi Shawl.

Art copyright © 2024 by Jabari Weathers

Versions of this story have appeared in Nightmare Magazine; The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2017 published by Mariner Books; Making History: Classic Alternate History Stories published by New Word City; and the anthology Our Fruiting Bodies published by Aqueduct Press.

Buy the Book

Vulcanization