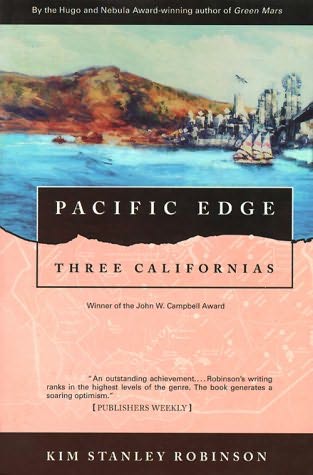

Pacific Edge (1990) is the third of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Three Californias trilogy. (Don’t scroll back thinking you must have missed posts on the first two—you haven’t.) The idea of the Three Californias is that Robinson wrote three novels all set in the fairly near future, 2065, and all set in Orange County, California. Three possible futures, three ways the world might be, three angles on the same place, with one recurring character and some recurring themes and motifs—The Wild Shore is post-nuclear, The Gold Coast is cyberpunk, and Pacific Edge is utopian. All of them begin with the characters disinterring something from the twentieth century.

I’ve often said that Pacific Edge is the only utopian novel that works, that shows you the world, that feels like a nice place to live, and that works as a story. The problem with utopias is that they don’t change, and because in science fiction the world is a character, the world has to change. You can write a story set in utopia, but it has to be a small scale story of love and softball, because when you’ve got there, there’s nowhere to go. (It does occur to me that you could have a tragedy of the end of utopia, which would essentially be Paradise Lost, which might be an interesting thing to do as SF. But I can’t think of an example.) The typical thing to do with utopia is the story of a visitor being shown around, and while there are interesting variations on that (Woman on the Edge of Time, Venus Plus X) it’s usually pretty dull. What Robinson does with Pacific Edge is to tell a small scale story—a fight to preserve a hilltop, romance, softball, architecture—and embed within it in diary form the story of how the world got from here to there. Because that story is there, in italics, commenting and underlining, the whole book gets grounded, and we see the world change.

Not everybody likes Pacific Edge. Sasha, after gobbling up the other two, choked on this one, saying it was boring. I don’t find it boring in the least—the one I find boring is The Gold Coast, his favourite, which leads me to wonder if anyone really likes all three. As well as doing different futures and different styles of SF, Robinson does different prose styles. The Wild Shore is stylistically a lot like Pangborn’s Davy, and before that Twain, very folksy and American. (My favourite bit in The Wild Shore is Tom teaching the kids that Shakespeare was the greatest American ever, and England one of the best states.) It’s also California as neo-wilderness. The Gold Coast is all slicked down and Gibsonian, and all about making money and weapons. And I realised on this read that Pacific Edge is stylistically very like Delany.

What makes Pacific Edge utopian is not that the multi-nationals have been disbanded and everything is small scale, socialist, green, and quietly high-tech. (There’s even a Mars landing watched from Earth, as in Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain, which makes me wonder if that’s an obligatory ingredient in a left-wing SF utopia now.) What does it is that in the major conflict of the novel, the two alternatives are leaving the mountain as wilderness and parkland, or building a commercial zone with restaurants and parkland. Even the worse option is really surprisingly nice. In the personal conflict too, Kevin and Alfredo both in love with Ramona, the resolution is surprisingly low key and peaceful. When Kevin talks about an intensity of feeling lost with all the communal living and talking it out, he’s right. It’s Tom who grounds the novel, both connecting it to the past and the wider struggle, and it’s Oscar, the lawyer from Chicago, who makes the general athleticism and communal homes seem plausible by being fat and living alone.

The central core of the novel is Tom —Tom links past and present, as he links all three books. Tom in the past meditates on utopia and hope and ways of getting from here to there. Tom’s misery in the internment camp in a near-future US that seems closer now than it did in 1990, grounds the general cheer of the actual utopian sections. Central to Tom and to what Robinson is doing is his meditation on his eighties Californian childhood, growing up in utopia, in a free country full of opportunity, but a utopia that was grounded in exploitation in the Third World and pollution of the planet. The key sentence, as he vows to work for a better world is: “If the whole world reaches utopia, that dream California will become a precursor and my childhood is redeemed.” That’s imperialist guilt in a nutshell, but in this book with its small scale issues of water in California and softball games we’re constantly being reminded that the rest of the planet is there, in a way that’s quite unusual in anglophone SF.

Robinson’s ideas on communal living, and his green lefty ideology generally, are better conveyed and more appealing here than when he comes back to them in Forty, Fifty, Sixty trilogy. I’m mostly in broad agreement with Robinson—and I think it’s worth saying that when discussing a political novel. I can imagine people who truly believe that profit is the greatest good getting quite angry with this book, but I can also imagine it making them think. With the later trilogy, I was gritting my teeth even where I agreed and rolling my eyes where I didn’t—in Pacific Edge I think he found the right balance to make the world interesting and the ideas thought-provoking. I don’t think for a picosecond that everyone will want to live communally, but I didn’t think “Oh come on!” when I saw it here, and only noticed it especially because of remembering how it broke my suspension of disbelief in Sixty Days and Counting. There’s a little of Robinson’s mysticism, and no sign of Christianity—which seems weird now I think of it, but which I didn’t notice while I was reading.

1990 is twenty years ago now, so there are ways in which this feels like yesterday’s tomorrow. Computers and telephones aren’t personal and ubiquitous, and the connections he imagines across the world—houses twinned with other houses—seem quaint, as do the messages left on the TV. I’m quite used to this feel in older SF, but these are books I read when they came out, I think of them as being fairly recent. It’s odd to think how much more the world is connected together right now than Robinson imagined it would be in fifty-five years. We’re no closer to utopia—or if we are, then not the one Robinson was after.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

I think it is probably more appropriate to call the California books a triptych rather than a trilogy. They are thematically linked, but not structurally or in terms of plot.

Your timing is also off. KSR didn’t have an eighties childhood in California, but a sixties childhood. That makes a huge difference, especially for someone who grew up in Orange County, as he did. Several authors from that generation saw and were clearly marked by the rapid transition from orange groves to strip malls.

This is definitely my least favorite of the three books. The tension just doesn’t work for me, though perhaps I need to go back and read it again as a full grown adult, rather than someone in his twenties.

I should reread the trilogy, it’s been a while. This was certainly my favorite book of the three – I remember the world building reminded me of Ecotopia by Ernest Callenbach.

This is also my least favorite of the three, for reasons you’ve mentioned: even the bad options aren’t really so bad, so the stakes don’t feel particularly high.

Strikes me that Arthur C Clarke’s The City and the Stars is essentially an end-of-utopia novel, since there’s nothing particularly wrong with life in Diaspar, except for the occasional problem of people like Alvin showing up.

I like them all….

I gave up halfway through the first softball game. I never bothered with the other two, but if nobody likes all three I’ll give them a shot.

I didn’t find this one boring, but I did find it less interesting than the other two (or the Science in the Capitol trilogy, for that matter). I agree it’s more interesting than most utopian novels, but that’s not a high bar to clear. The Gold Coast is the only one of these that I’ve re-read, though I plan to re-read all three eventually.

Demetrios: I wasn’t talking about Robinson but his character, Tom, who was, according to the text, born in 1984.

I definitely think that it’s true that no one likes all three of these books – and also that while Robinson has written several of my favourite books ever, he’s also perfectly capable of writing books that I can’t stand, i.e. The Gold Coast. I did enjoy Pacific Edge, but The Wild Shore is the best of the three in my opinion; something about the depiction of the world really grabbed at me much more in that one.

(Although I didn’t think that the second and third books of the Science in the Capital trilogy were great, I have read and re-read Forty Signs of Rain many times. Picking it up four days after Hurricane Katrina may have had something to do with how intensely apt it seemed, though.)

Jo: Ah, I reread it and I see I misunderstood a pronoun reference. My comments about KSR’s Orange County childhood are still relevant though. In the mid-50s, OC was largely agricultural and semi-rural, but by the early 70s it was almost fully incorporated into the SoCal urban sprawl.It seems like every modern author who lived there during that period has to write about it at some point.

I’m still not real keen on this one. The Wild Shore is probably my favorite, though that appreciation is colored by factors not directly connected to the book. KSR was my freshman writing instructor at UCSD in 1980 and I eagerly grabbed the book when I found it over whatever break it was when it was released. I wound up reading quite a bit of it on the train down to SD and found myself looking out the window and identifying locations from the book. All of that made it very personal for me.

I think Aldous Huxley’s last novel, Island, is a utopian novel where the utopia ends (or rather, is destroyed) by the end. It’s almost SF, in a mystical sort of way.

Maybe they’re utopias all three of them?

I liked all three books, and was a little less involved in this one than the others, but I agree that it’s a really interesting approach to utopia. I didn’t see it as a low-stakes story; to me at least, the idea that the utopian revolution has pretty much succeeded but that it took a whole lot of work, and that there are (and may always be) plenty of people who’d like to drag things back down – and they’re not supervillains, they’re just typical money-driven people of our time – was unsettling, because there clearly wasn’t going to be a big final conflict that you could win and then feel safe after.

Also, I wonder if other people found the death scene in the ocean as moving as I did. It’s not anyone’s fault and it doesn’t really have anything to do with the story (except kind of theoretically, by making the point that in a utopia people will still die and won’t like it, even though they would’ve had a worse fate if they’d been in one of the other two books)… but it’s still suspenseful and tragic, at least for me.

One of the most absorbing things for me about the three (trilogy, tryptich, or what you will) is how they announce KSR’s career and concerns. We’ve had occasional authors whose careers focused on one area of personal concern (pre-Dune Herbert is about ecology, for instance), and KSR is “about” “development”.

When I think of utopia stories I always go back to BF Skinner’s Walden Two. As a story it is kinda lame, but the sheer prescriptiveness and purity of vision is thrilling.

I’d like to give this book a chance – I think the question of whether modern utopias are by necessity not inclusive of the whole population is key.

Count me as another person who didn’t like The Gold Coast but liked the other two. (Anyone here who didn’t like The Wild Shore, but did like the others?)

I need to reread this one now that I’ve lived in California.

Sorry for the late response, but I’m the person aleistra was looking for — didn’t particularly care for The Wild Shore, loved The Gold Coast and Pacific Edge.

And for another data point: in the early 90s Robinson was one of my favorite authors, and Pacific Edge was probably my favorite novel of his. But I completely gave up him after Antartica and the reviews which indicated the next book he wrote was even more preachy.

Colomon: Some of his books are preachy, but he has written some brilliant books since Antarctica, especially Years of Rice and Salt.