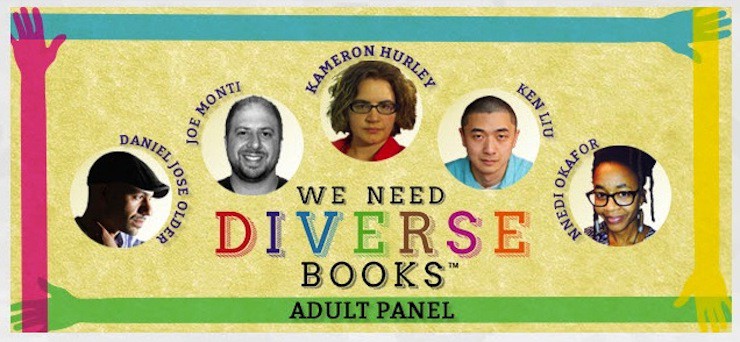

A year after its establishment, the We Need Diverse Books movement brought two engaging panels to BookCon 2015, partnering with bestselling authors to address the need for greater diversity in sci-fi and fantasy and children’s literature. In the panel In Our World and Beyond, SFF authors Kameron Hurley, Ken Liu, Nnedi Okorafor, and Daniel José Older, along with Saga Press Executive Editor Joe Monti, discussed the obstacles to depicting full representation of marginalized characters in SFF.

The panel discussed whether SFF should be political, and even tackled the term “diversity” itself—how politically correct it is, and the difference between a U.S.-centric diversity movement and the adoption of more global perspectives. Read on for the highlights!

Diversity is Truth

From the start, Older (author of Half-Resurrection Blues) established that “diversity is about the truth. When we’re not writing books that show the [truth] of the world, we’re lying. A lot of the history of literature has been the lie of a non-diverse world.”

Hurley (The Mirror Empire) recalled having a similar experience when she first read SFF, thinking “Wow, everyone’s lying to me” about space being populated only with white men. In fact, she pointed out, “if you live in a space where everyone is homogenized to be the same, that’s a political thing they did…. I grew up in an SF dystopia.” When told that her books were “niche, feminist books full of brown people,” Hurley responded, “The audience is the world. I’m proving the audience exists. It’s stupid that we have to prove the truth.”

Liu (The Grace of Kings) stepped in to add that he’s actually a little uncomfortable with the word “diversity” and how it has been used: “Often it’s been exoticized that if you look a certain way, there’s a certain story expected of you. That’s problematic.” He advocated that, instead of all trying to go against one normal curve (as on a graph), we should turn the world into a scatter plot: “Individuals are not diverse. Collectively, we are.”

Okorafor (The Book of Phoenix) shared her experience growing up, in which all of the fantasy she read was populated by white characters. The only nonwhite characters were nonhuman creatures or aliens. “When I looked back,” she said, “I noticed that I migrated towards those books that did not have human characters, because I could relate to those characters more than the white characters. I didn’t see reflections of myself in what I was reading.” Diversity, she said, is necessary for readers.

“To not see [diversity] represented in fiction is not true, and is bad business,” Monti said. “Once you start publishing toward a wider audience, you’re going to get a wider audience.”

Should SFF Be About Social Commentary or Fun?

The recent controversy around the Hugo Awards prompted moderator Marieke Nijkamp to ask the panel whether they believed SFF was political.

“I wish it went without saying,” Older responded, “but SFF has always been a political endeavor. But it’s always been a very colonial, racist, political endeavor. It’s a normalized form of politics, that especially white dudes are used to seeing themselves destroy the world and that being a victory and a good thing. That’s not political to them, that’s how it should be.” “The status quo is not a neutral position,” Hurley added.

Conversation turned to counter-narratives that push back against the status quo–not to please certain people, Older clarified, but to talk to each other. That dialogue requires consideration of “diverse rhythms, diverse narrative structures, diverse ways of being, diverse conflicts.” Hurley added that pushback begins not at reaching parity, but simply reaching 1 in 3 people. “You’re getting through to people,” she explained, “you’re making people uncomfortable. There’s this thinking [by white men] that ‘you’re gonna do to us what we did to you,’ and I think that’s where they’re coming from. I see that in feminism all the time: ‘Women are gonna treat men the way men treat women,’ that fear they have. And we’re like, ‘No, we’ve learned. You’ve taught us well!'”

Liu took a different tack, explaining that some pushback comes from people assuming that political fiction will be written with the same narrative structure as a political screed, when that’s not the case. “Fiction persuades by experience,” he said. “It’s a way to get you the reader to experience a different way of thinking and looking at the world. The power of diverse fiction is that it helps you and everybody to realize just how colored the lens through which they look at the world is, that there are other ways of thinking, living, and being. They are just as valid, just different from yours. What is the point of reading SFF, other than to experience these different modes of thinking?”

Okorafor has found that when she or fellow Nollywood (the Nigerian Hollywood) colleagues have worried about the consequences of presenting sensitive issues, she’s suggested, “Why don’t you write it as SFF?” In this way, they have been able to present issues that are either highly sensitive or have been beaten into the ground so much that people don’t want to hear about them—in short, to make them new again.

How to Unpack Discussions of Diversity in SFF

For one, calling something diverse is using politically correct language, Hurley pointed out. “Instead of just saying ‘diverse,’ say what you’re actually saying,” she said, pointing to examples of a table of contents that has only white men on it, or writers who share the same class background. The next step in the discussion of diversity is to go from being “nice” (i.e., raising the issue) to “getting right in people’s faces.”

“The use of euphemisms is problematic,” Liu agreed. “We’re very interested in being polite, because we think it’s the only way we can be taken seriously.” He added, “I like to say in SFF that every dystopia is a utopia for certain people. We have to find out who those people are” and why they get upset when the status quo is challenged.

Older referenced Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s closing speech at the PEN World Voices Festival, in which she said that in the U.S., “the fear of causing offense, the fear of ruffling the careful layers of comfort, becomes a fetish.” This emphasis on comfort creates silent forms of censorship, Older said: “When we look at the publishing industry and how white it is, we have to understand there is [a form of] censorship at work.”

Monti pointed to the old adage that the golden age of sci-fi is 12. A recent editorial in Strange Horizons has challenged that number, claiming 29 is the golden age. In the same vein, Monti said, “The so-called minority are going to be the majority.”

“The diversity movement on the whole is a very U.S.-centric movement,” Liu pointed out. “To truly get the full range of human experience, we have to look beyond the U.S…. Real diversity, whatever that means, has to be the kind of all-encompassing vision of all of humanity, not the few percent who… are able to claim their words are the best.”

How to Avoid Stereotypes or Token Characters

“Before I wrote God’s War, I probably did eight years of research into the Middle East, Judaism, Islam, Catholicisim, and all sorts of fabulous other things,” Hurley said in response to an audience question about how to not fall into the trap of stereotyping nonwhite characters. “You’re gonna get stuff wrong. You talk to as many people as you can, you do as much research as you can, you have beta readers—no matter how well you do it and how good your intentions are, you are going to get something wrong…. Know that you’re gonna screw up, and be OK with it, and do better next time.”

“One of the things that I’ve found really helpful,” Liu said, “is for those of us who don’t belong to the majority culture in the U.S., all of us seem to have a kind of double-gaze. We can see and experience the world in our own way, but we can take on the view of the majority with fairly good accuracy—far better than the other way around. It’s actually very helpful, because the way we avoid stereotyping white ways of thinking is because we can embody that consciousness in a way that isn’t seen as research, as trying to do something exotic or strange, it’s just treated as ‘we are trying to learn the way the world works.'” The key to avoid stereotyping is to try to exhibit and inhabit that point of view the way people already do with the white perspective.

And if you’re strapped for cash and unable to travel, Okorafor said, “I ilke to go to a restaurant. Listen to people, eat the food, take in the aromas and the talk.”

Takeaways for the Audience

“Please don’t be quiet,” Hurley said, whether it’s in-person or on social media. “It’s by being loud and persuasive and awesome that has gotten us this far.”

“What you can do as readers,” Liu said, “[is] don’t give up, and demand more books that are actually good, that reflect the reality you live in.”

“If you don’t see an example of what you want to write out there, don’t let that stop you. Just create your own path,” Okorafor said. “Beat your own path. It’s harder—you have no examples to follow—and that’s fine. The obstacles are there, but there are always ways around it, over it, under it.”

Older read Okorafor’s novel Zahrah the Windseeker “to make sense out of shit” when he was an unpublished writer, “trying to figure out if this was even possible or feasible.” He pointed to her novel as an example of inspiration, as well as Antonio Machado’s poem that goes Caminante, no hay camino / Se hace camino al andar (“There is no road, lonely wanderer / The road is made as you march”). “History came from people of color taking risks,” he said. “We cannot forget that.”

Sounds like it was a good discussion.

Interesting topic with no simple answers; which is good honestly.

Real life isn’t made up of simple answers.

I liked how they all emphasized that it has to be good & not just ‘diverse.’ That diversity can enhance good writing but that that writing is not good simply for being ‘diverse.’

I am sorry for breaking convention on the care & feeding of certain internet creatures but having been inspired by Jo Rowling’s recent posting to a less than Christian christian church I felt that this quote from Mark Twain is pertinent:

“It is better to keep your mouth closed and let people think you are a fool than to open it and remove all doubt.”

Kato

@@@@@ Kato: good quote.

Thinking I’m glad to have missed comment #2.

Max Livingston & Brent Weeks is doing a decent job of showing diversity in good writing.

Lois McMaster Bujold is becoming better at including non-white ethic diversity. She’s always had one of the best physically handicap characters, but his world was very European.

And while the Betan’s are very accepting of everything, the most we have meet are European in description.