Though he wanted to love it, an old friend of mine grew irritated with the N64 version of Rogue Squadron because after getting bombarded with unseen TIE Fighter missiles, he threw up his hands saying the game was “way too hard.” For him, a Nintendo Star Wars experience should be more like the films: fun, with action and adventure that’s easy to experience and quick to digest.

And because Rogue Squadron (the entity) exists in that 1996 video game and also in this 1997 novel, my friend’s frustration might be the most perfect metaphor for how to think about the X-Wing novels. They’re fun, and chocked full of great Star Wars stuff, but after a while, they start to seem like a lot of hard work.

To be clear, revisiting these books has been both surprising and reassuring. Surprising, because I actually expected to find them more tedious at 32 than I did at 14, and reassuring because it’s nice to know I had good taste back then, too. Like a lot of the authors writing in the Star Wars expanding universe, Michael Stackpole treated what he was working on like a work of historical fiction. As Hilary Mantel is currently imagining the machinations of the War of the Roses court of Henry VIII with Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, or Jim Shepard gives us a sideways historical look at the invention of the guillotine in “Sans Farine,” the events of Star Wars are treated with equal attention to detail and literary research. A long time from now, in an anthropology class far, far away that future historians might confuse all these Star Wars books for actual historical texts of something.

But, unlike actual historical fiction, Star Wars books don’t have original documents; instead there’s just the Star Wars movies and/or other Star Wars books. With certain established events changing because of new films or George Lucas actually re-writing history, it’s easy to see how these books start to sink into a swamp of continuity problems. And even though the X-Wing books are fairly isolated insofar as they don’t feature “main” characters or even “important” historical incidents, after a few entries you start kind of scratching your head contemplating how a compelling story can be told in this galaxy if it doesn’t involve people fighting the man.

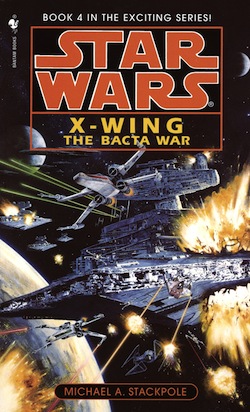

Picking up where they last book left off, The Bacta War reintroduces us to Corran Horn and his main hobbies, which are: (1) convincing himself he doesn’t want to become a Jedi Knight, and (2) going back to prison Lusankya and liberating his buddy, old man General Dodonna. In case you forgot, General Dodonna (he’s a person and his first name is Jan) was the bearded dude who explained to everyone how to blow up the Death Star in A New Hope while suspiciously kind of mispronouncing Leia’s name.

Corran’s desire to go back and liberate this prison is a passion shared with the rest of Rogue Squadron, since it all dovetails nicely with their desire to get control of the supply of Bacta away from cartel on Thyferra. However, none of the legitimate government officials actually want to back this idea for a lot of political reasons which are actually not worth getting into. Stackpole (and many of the other expanded universe novelists) do a great job of convincing us the galactic politics are what the makes the galaxy go around, but it only becomes interesting when a small group of people stands up to those rules and says “no.” This works in the original Star Wars, and um…works in a Star Wars book, too.

Rogue Squadron can no longer officially be part of The New Republic because they have decided to make a hit on something The New Republic can’t support. So, just like in their old Rebel Alliance days, the Rogues are going to have to make do with what they can cobble together; everything from special parts to a secret base and Rogue squadron becomes more rogue than ever! All of this is totally fantastic and actually makes for one of the most fun reads of the series so far. But it’s not my favorite, and that’s because it feels a little bit like a reset button, and there something happening here which seems to infiltrate a lot of big speculative franchises and it weirds me out.

Babylon 5’s fifth season wandered a bit because the story became about establishing a government. The beginning of Battlestar Galactica’s third season began with depicting day-to-day life on a newly established colony. In both of these cases, things needed to get blown up in order for everyone to be interested in everything again. Hell, even every third or so James Bond movie features the secret agent “going rogue” in order to make everything exciting.

Having action-adventure stories suddenly become about politics—however fanciful—creates a weird identity crisis within the storytelling mechanism. Star Trek: The Next Generation writer Morgan Gendel once told me that one of his goals with the episode “Starship Mine,” was to have Picard “kick a little more ass.” Do we always have to destroy civilization to make things more fun? Well, probably not, but the biggest difference between Star Trek and Star Wars is the former pulled off having long, dull conversations as the centerpieces to excellent hours of television, simply because you’re dealing with an hour and not two. Space politics for a whole novel? No way! Let’s get those Rogues off the grid!

The Star Wars prequels are largely about space politics and how a government unravels, while the Star Wars Expanded Universe novels—at least the ones that helped keep the Force alive in the ’90s—are also about space politics. In a way, it shouldn’t be too surprising that the prequels turned out the way they did, because if George Lucas had been reading some of these books (come on, maybe he did) he’d be like “I guess this is what the fans want.”

To be fair, The Bacta War, even with its space politics and “unimportant” characters still has more romance and heart that the Star Wars prequel films ever did. There’s a little notion I like at the beginning of this one, where Corran is thinking back on the “holodramas” that “painted the Jedi as villains.” Not only do I love thinking about these propaganda movies being directed by Palpatine (remember when he felt bad about everything?) but I also like the thought Corran has after it. In recollecting his childhood impressions of the Jedi, Corran remembers thinking of them as “vaguely romantic, but too sinister.”

I love this description, because it makes them sounds like pirates. And even though it would be crappy to be a real pirate, and playing a realistic video game about pirates would get old, we all know how we feel about pirates: they’re fun.

Which is the same way we think about mixers, rebels, and rogues.

Ryan Britt is a longtime contributor to Tor.com.