“Banquets are extremely important occasions,” said Mr. Noah, “and real food—food that you can eat and enjoy—only serves to distract the mind from the serious affairs of life. Many of the most successful caterers in your world have grasped this great truth.”

How many of us have wanted to enter, really enter, the worlds we have built, be they built with toys or words or fellow playmates? And find those worlds filled with copious amounts of hot chocolate, adorable talking dogs, and a parrot with a tendency to quote the Aenead?

Okay, maybe not the parrot. But otherwise?

Because in The Magic City, Edith Nesbit allows her two child protagonists, Philip and Lucy, to do just that, creating one of her most delightful, laugh out loud novels, in a return to the style that had served her so well in previous books.

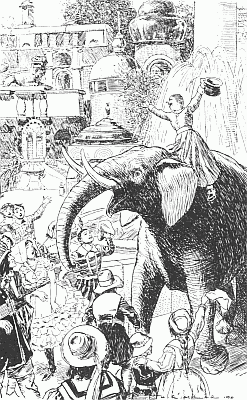

The novel opens with Philip discovering that his considerably older half-sister Helen, who is also his guardian, is about to marry Lucy’s father, combining the two households. Lucy is excited; Philip is not. Severely traumatized by the move, he is outright rude to Lucy—and everyone else—and turns to building cities from Lucy’s toys, much to the distress of Lucy’s nurse, who does not think Philip should touch any of them, and hits him, threatening to destroy his cities. An upset Philip decides to look at the cities by moonlight. Which is lucky, because as we all know, moonlight is the time when magical things happen—including getting dragged into toy cities and finding that they are quite, quite real.

Naturally, like any magical country, the place does have a few flaws. For one, the laws of banquets decree that in the city, first everyone must be served with fake wooden toy food before the real food gets served, which is equivalent to massive torture if you’re a young kid flung into a magical land by mistake. For two, Philip doesn’t get to enjoy the magical land by himself—a curious Lucy has followed him, and no matter how much he resents her presence (which is quite a lot) he can’t make her leave. For three, as Mr. Noah, from a toy Noah’s Ark, solemnly informs them (with some difficulty; he’s not used to thinking since he doesn’t have to do it often, and the process distresses them) they believe that Philip just might be the Prophesied Deliverer.

And as all good Deliverers must, this means Philip must perform a quest. Specifically, he must finish seven tasks—alone or with help—starting with slaying a dragon. (In an unintentional foreshadowing of later steampunk novels, the dragon just happens to be a clockwork dragon. Yes, really. I will publicly admit that I cackled. ) And, to become the deliverer, he must complete these tasks before his enemy and rival, the Pretender-in-Chief to the Claimancy of the Deliverership can do so. (To save everyone the effort of trying to say this every few pages, her title is promptly shortened to the Pretenderette.)

Completing the tasks requires Philip and Lucy to explore the world that Philip has—however inadvertently—created with his toys and tales. This is a child’s world, where certain dangers can be combated with child logic. (For instance, if you are facing fierce lions that were once toys, you can tie them down, and then lick and suck the paint off their legs, which will weaken the lions and allow you to break them apart. I can think of no other book—well, children’s book—that advocates licking an enemy to destruction.) It also means grand adventures seized from books and imaginary plays—adventurous islands, rushing rivers, waterfalls, desert journeys, and happy islanders focused on playing games, who use poor graduate students as nearly-slave labor. The graduate students apparently find physical labor easier and more desirable than studying math. As I said, a child’s world, although Nesbit takes a moment or two to take a few well aimed potshots at the British university system.

And, outside of the banquets, the world is also filled with marvelous food—endless hot cocoa served with large dollops of comfort food, assuming that you are willing to sit through rather questionable banquets first. The end result is a glorious mix of Oxford jokes, desert journeys, enchanted islands, magical rivers, very tiring sloths, and, oh, yes, some barbarians from Gaul and Julius Caesar, somewhat more kindly disposed towards women than his usual wont.

(Exactly what Nesbit’s obsession with Caesar—this is about his third appearance in her novels—was, I don’t know, unless she felt that he would be a reliably recognizable historical figure. But here he is, again, not assassinated yet.)

But this is not merely a story of magical cities and toys come to life, but also a story of learning how to make friends and take responsibility and grow up. As Philip learns, his toys can only help him to a certain—very limited—extent. (Like, say licking paint off toy lions.) For actual assistance and ideas, he needs humans, and to a lesser degree, the parrot. This is made even more explicit by the end of the novel, when Philip and Lucy realize who their enemy is.

Which is also when Nesbit takes a moment to drop in more of her frequently brutal social commentary. As it turns out, the Pretenderette has become a villain for a few different reasons: for one, she honestly thinks, in the beginning, that this is all a dream, and therefore, whatever she does doesn’t matter. For two, she has never been loved. And for three—she has been a servant. A job, as it turns out, that she has hated—largely because of the way her employers treat her, and because she has spent her life, as she says, watching others get the fat, while she gets the bones. Like Philip, she did not become evil by accident, but by circumstances, and Nesbit makes it clear that the English class structure can and does foster bitter resentment.

Which, admittedly, does not make the lower upper class Philip any more likeable at the start of the book. Lucy calls Philip, with reason, the “hatefullest, disagreeablest, horridest boy in all the world,” and I can’t help but think that she has a point. (On the other hand, he is of the firm belief that cherry pie is appropriate breakfast food, and I also can’t help but agree with him there.) He also, to his misfortune, knows absolutely nothing about girls, which is not helpful when you are trying to travel through a magical land with one. And he is frequently, if understandably, afraid.

Philip’s bad behavior is not completely unreasonable—he’s upset and scared about losing the home he has shared with his older sister, a nearly perfect parent, for all of these years. This both allows child readers to easily identify with him—who at that age isn’t scared of a major family change?—and allows Philip to do some rather less reasonable self-justification for being just awful. Readers are, however, warned: when Philip faced the dragon, I was cheering on the dragon, and not because of my general love for dragons—Philip is just that awful.

But he changes.

The often cynical Nesbit had never allowed her only slightly less awful Bastable children to change; and if the children in the Psammead series had learned something from their many, many errors—or tried to—they did not learn that much, and their basic personalities never changed.And she does not make the mistake here of giving Philip a complete personality change. But she does allow Philip tolearn to change his outwardly behavior—and learn to make friends with Lucy—in one of her few examples of maturity and growth.

Speaking of Lucy, she’s another delight in this book: spunky, adventurous, fast thinking, compassionate, quick to call Philip out for being a jerk, and brave; my only real complaint is that the book’s focus on Philip relegates Lucy to a secondary character.

As always, I have other quibbles. After finishing the book, I had to question just how Lucy ended up as the nice child and Philip as the child with the multiple issues—although I suppose this is Nesbit’s quiet way of defending her own tendency to neglect her children. Still, Lucy’s self-confidence, under the circumstances, seems a little odd. And 21st century kids may find the references to some of the toys confusing—I had to ask my mother several tedious questions when I initially encountered the book, and she had to send me to the librarian. (Which just goes to show that librarians know EVERYTHING.)

But these quibbles aside, The Magic City is one of Nesbit’s best books, an assured, often hilarious romp through an imaginary world, brimming with magic and my chief complaint was having to leave it at the end.

Mari Ness hasn’t yet managed to step into imaginary worlds, but she’s keeping an eye out for fantastic portals—which is why she has temporarily abandoned her central Florida residence for a stop at World Fantasy Con this week. This also means her answers to comments will be a bit delayed.