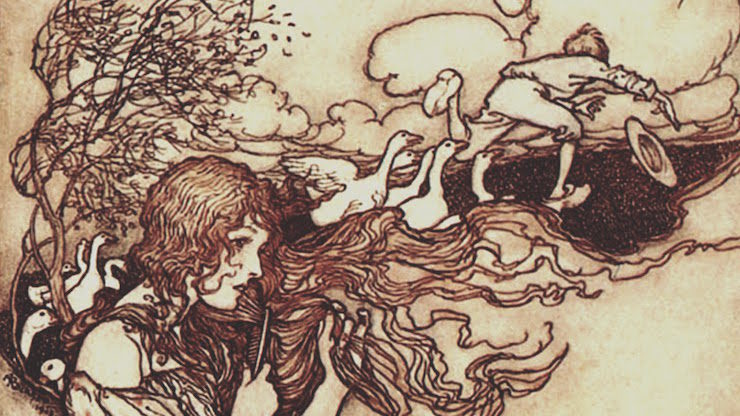

In many ways, “The Goose Girl,” collected by the Grimm Brothers, is the quintessential fairy tale—containing magic, a talking animal, unexpected brutality, swift changes of fortune, a false bride, and a happy ending.

Except for one minor detail: Are we really supposed to be cheering on the heroine? Really?

It’s not that I can’t sympathize with the poor girl, who does go through quite a lot. As the tale starts off, she’s about to head off to a foreign country to marry a complete stranger, escorted only by a single waiting-maid, not the military escort a princess could reasonably expect. Anne of Cleves, for instance, was accompanied by 263 attendants and 228 horses when she made her way to Henry VIII, and she was considered a minor princess. And although the princess’ mother does send her off with some nice clothes, a few jewels, and a talking horse, those presents also include a rag stained with three spots of blood. Three talking stains of blood, at that, which is disturbing however kind the intention. Books make a much nicer present and are more fun to take on a trip. I’m just saying.

And as it turns out, her mother is not exactly great at choosing servants: just one hour into the trip, the waiting-maid refuses to get the girl a cup of water, announcing that she has no plans to be a servant, which, ok, then, why did you sign on for this trip? And also, queen, for the record, next time try to find a servant who is willing to put in at least one day before dropping the profession. Just a suggestion. A few hours later, and the waiting-maid forces the princess to exchange clothes and horses. When they finally arrive at the palace, the prince naturally assumes that the woman dressed in royal clothing must be the princess, and greets the maid as his bride. Great planning there, queen.

Anyway, the waiting-maid immediately arranges to have the talking horse killed. That would be depressing, except that the princess manages to save the horse’s head, which decides to respond to all of this by talking in rhymes even though technically IT’S DEAD, which creepy, but not really the important part here. The princess is sent out to help a boy called Conrad (in most English versions) tend the geese, something that would go better if she weren’t constantly distracting Conrad by blowing his hat around. On the other hand, this gives the king his first clue that something might be up, letting him discover the deception.

It’s a great story, with just a few little questions, like, why did the horse wait until he was dead to start identifying the princess through rhymes? Mind you, I’m by no means certain that people would have paid more attention to a living talking horse than a dead talking horse—in fact, arguably people would and should have paid more attention to a dead talking horse—but the time to speak up, horse, was not when you were dead and hanging on a gate, but when you first arrived in the courtyard and the prince was greeting the maid.

Also, how, exactly, did the waiting-maid think she would get away with this? In other tales of false brides, the false bride and the prince (or king) generally live in a distant kingdom. In this case, the marriage between the prince and the princess was arranged, suggesting that the two kingdoms have some sort of communications system. Letters, perhaps, brought back and forth by ambassadors or traders. And the two kingdoms don’t seem to be all that far apart—there’s nothing to indicate that the princess and her maid needed to spend a night at an inn or something on the way.

Which in turn suggests that someone from the kingdom of the princess might have visited the palace, or watched the members of the royal family ride through the streets, and noticed a slight problem. Then again, maybe the waiting-maid counted on everyone being nearsighted. Eye-glasses were certainly around when this tale was recorded, but not all that common, and one blurry face seen at a distance looks rather a lot like another blurry face seen at a distance.

And speaking of questions, why did it take little Conrad so long to inform people that his new coworker was talking to a dead horse that talked right back to her? This is the sort of thing that needs to be reported to HR, like, immediately. Or the fairy tale equivalent of HR. Get your fairy godmother on the way, now.

But it was not until I was an adult that I started to really question the story, noticing a few small things along the way, like:

- That blood thing. Specifically, that talking blood thing. Even more specifically, the old queen is sitting around, leaving drops of talking blood in handkerchiefs, not exactly an ability associated with most queens, in or out of fairy tales.

- The princess herself has the ability to summon the wind and send hats flying through the air.

- Come to think of it, this is not a very nice way to treat poor Conrad.

- Not to mention the grimness (I know, I know, but I can’t resist the pun) of the chambermaid’s fate: to be placed stark naked into a barrel lined with sharp nails, and then be dragged behind two horses in the city streets. It means death, and a painful death. And come to think of it, why exactly does the chambermaid voice such a cruel punishment? Is she simply so foolish or self-absorbed that she fails to realize what’s going on? Or just too nearsighted to tell that she’s near the princess? Or, is she aware that this is a trap, and thus, frantically trying to come up with a punishment that sounds deadly but might offer a hope of escape—after all, at least her head will be on her shoulders after getting dragged through the streets? Probably not, since the punishment includes the rather foreboding words “until she is dead,” suggesting that survival is probably not an option here.

Or—is the princess somehow compelling her to speak?

I hate to cast aspersions on fairy tale characters. Really, I do. But looking at all of the above—and adding in their ownership of a talking horse—I can only conclude that both the princess and her mother are practitioners of magic, something generally frowned upon in many fairy tales unless performed by a good-hearted fairy—that is, someone not entirely human. Oh, certainly the Grimms recorded the occasional exception—as in their version of Cinderella, or in “Brother and Sister,” and a few other tales. (And it should be noted, in this context, that in their version of Cinderella, the stepsisters have their eyes plucked out by birds apparently summoned by Cinderella.) But for the most part, magic is associated with evil.

So consider this, instead: the waiting-maid has spent her entire life hearing tales of the old queen’s magic—tales that, as we find out, are quite, quite true. She is sent off to an unknown land with the princess, without guards or other servants, rather suggesting that the queen thinks the princess is magical enough that she doesn’t need protection. And there’s this whole issue of a talking horse.

Is the maid, perhaps, only trying to assert herself against the princess for her own safety? And, having succeeded, bravely chosen to do what she could to defend an unknown kingdom against the dark magic of the queen and the princess? A princess who would—days later—compel her to speak her own doom? As the person standing up against magic, isn’t she, perhaps, the true heroine of the tale?

The Grimms, it must be noted, were particularly proud of this tale, which, they declared, was more ancient, beautiful and simple than the corresponding French story about Bertha, the betrothed wife of Pepin, as further proof of the superiority of German culture and traditions. (Proving the superiority of German culture and traditions was one of their main motivations.) They also pointed proudly to the story’s insistence that nobility was inborn, and could be maintained even after a distinct drop in social class—a frequently heard theme after the French Revolution. An insistence that also affirmed that displacing royalty was at best a temporary situation—in another echo of events after the French Revolution, but before World War I.

It all makes the tale not simply the happy story of a princess who uses her powers to control the winds, make dead horses talk, and arouse suspicions about just what is going on here, but rather more a story about what happens to those who try to overthrow the rightful government. Even if that rightful government is working evil magic. Royalty has power, the tale says, and will be able to use that power against those who try to overthrow them.

Or perhaps it is just a tale of a princess who uses her magic to get her rightful role back.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.