We would probably technically call Yod, the being at the center of Marge Piercy’s He, She and It, an android—an entirely man-made creation in the shape of a human—but Piercy opts for cyborg. It’s a telling choice in a book that’s full of them: a cyborg is an augmented human, a more-than-person. And Yod, though he believes he is a person, and a male, is more than either.

In the mid-21st century setting of Piercy’s novel, artificial intelligences that can pass as human are illegal. Lesser AIs—smart houses that carry messages and act as guards; robot messengers; even human-shaped creations with lesser intelligences—are a normal part of life, but Yod is a secret, created in a private lab. The tenth in a line of cyborg attempts, Yod is the only one of Avram Stein’s creations to function as planned. Some were too dumb; some were terribly violent, the result of the shock of consciousness, which Yod remembers being terrifying.

And wouldn’t it be?

Imagine appearing in the world with all the information, data, programming a human would think an AI needs—an AI built to appear human, with introspection, desires, and a great drive to defend, snapping into existence like a light. Avram’s co-programmer, Malkah, considers this and builds an awareness delay into Yod’s systems, so that not everything happens at once. This approximation of human growth makes all the difference.

But how much can programming replicate the process of learning, of experiencing the things that make you who you are? Piercy is interested in this question, but maybe more in the reverse: are humans just as programmed as her cyborg, and if so, how do these things relate?

In the realm of narrative psychology, a person’s life story is not a Wikipedia biography of the facts and events of a life, but rather the way a person integrates those facts and events internally—picks them apart and weaves them back together to make meaning. This narrative becomes a form of identity, in which the things someone chooses to include in the story, and the way she tells it, can both reflect and shape who she is.

This quote comes from Julie Beck’s fascinating Atlantic article “Life’s Stories,” which explores recent research about how the narratives we create for our lives can shape who we are. Normal, healthy adults, a professor of developmental psychology says, “can all produce a life story.”

Can you program that—or its equivalent? How can a consciousness act like a person when it comes alive in one fell swoop, without living the stories that make people who they are? How would an AI tell the story of who it is?

Avram, on some level, has considered this. He invites Shira Shipman, Malkah’s granddaughter, home to Tikva to work with Yod on his behavior. After years working for a corporate “multi,” where behavior is highly regulated and controlled, Shira finds it absurd that everyone refers to Yod as “him,” but as she works with Yod, practicing everyday human interactions, Yod grows. He becomes less literal, more adaptable, able to read people and understand their strange idioms and metaphors. Living through more moments that become part of his life story, he becomes more like a person.

Running parallel to the tale of Shira and Yod is the “bedtime story” Malkah leaves for Yod in the Base (Piercy’s version of the internet). She tells him about Joseph, a golem created in 17th century Prague to protect the Jewish ghetto. Joseph is a lumbering creature, a giant man possessed of incredible physical strength, but as he goes about his duties, he listens, and he learns. He has many questions, but not the ones a child would ask:

Why do parents love their children? How does a man pick a wife? Why do people laugh? How does someone know what work to do in the world? What do the blind see? Why do men get drunk? Why do men play with cards and dice when they lose more than they win? Why do people call each other momser—bastard—when they are angry and again when they are loving? You little momser. Why do people say one thing and do another? Why do people make promises and then break them? What does it mean to mourn?

These are not questions with easy answers; the best way to answer them is by living. But Malkah does the next best thing when she tells Yod the story of this other being who asked them. Her story is lesson and warning, a cautionary tale about being alive and at the mercy of your creator: unlike Yod, Joseph has not been given the capacity to change himself.

Malkah’s story is as much a part of Yod’s programming as any of her technical work. We are all programmed with stories: stories about our families, our countries, our world, ourselves. People have invented a million stories to explain the world; those stories then become part of people, of who we are and what we value, and the cycle repeats, each of us telling and creating and retelling, changing the details as we learn. By telling Yod the story of Joseph, she gives him a creation myth—a key piece of programming—of his own: You are not the first of your kind. Someone was here already. Learn from their mistakes.

Malkah is the reason Yod is a success, not just because she considered the terror of the cyborg equivalent of birth, but because she balanced Avram’s egotistical desire to create in his own image. Avram programmed Yod to be strong, logical, protective; Malkah gave him the capacity to change himself, a need for connection, “the equivalent of an emotional side.”

There’s a temptation to read this as a sort of gender essentialism, Avram providing the stereotypical masculine side of things, Malkah the feeling-side often attributed to women. But Piercy’s focus on how we’re shaped takes it back another step: these things aren’t inherent, but part of social programming. Yod, a fully conscious being that never had a childhood, comes to full awareness already imbued with the things that both men and women, in his world, are programmed to value and consider. He is both, neither, the kind of boundary-transgressor “Cyborg Manifesto” author Donna Haraway may have imagined when she wrote, “The cyborg is a kind of disassembled and reassembled, postmodern collective and personal self.” (Piercy name-checks Haraway in her acknowledgements, and the influence is clear.)

Malkah and Avram are just as much products of society as Yod is a product of their experience and knowledge; their input into Yod’s mind is a reminder that we too are programmed, told stories about who and how we should be. Piercy isn’t being reductive, but reflective of a flawed world that insists on different stories for and about men and women. By giving Yod both stories, Malkah frees him to choose the things that are—or become—important to his own existence.

And by telling this story largely through Shira’s eyes, Piercy crosses the human/machine boundary, giving us a compelling argument for the way people are programmed by the narratives we choose to value. Shira believes her life irrevocably shaped by the relationship she had with Gadi, Avram’s son, when they were young. It ended badly, and Shira told herself that she could never love like that again. It is one of her defining stories—but stories can be retold, personal myths reworked.

Early in the book, Malkah reveals to Shira that a key piece of her family mythology—the idea that each woman gave her child to her own mother to raise—was something Malkah made up to explain Shira’s mother’s disinterest in being a parent.

Shira found herself staring with slack jaw. “Are you telling me you weren’t raised by your grandmother, back to the tenth generation?”

“It was a good story, wasn’t it?” Malkah said proudly. “I thought you enjoyed it.”

But Shira felt as if all the rooms of her childhood had suddenly changed place. She was annoyed, even angry with Malkah for having lied to her, for making her feel foolish. In storybooks, bubehs made cookies and knitted; her grandmother danced like a prima ballerina through the webs of artificial intelligence and counted herself to sleep with worry beads of old lovers.

“It was a good story.” Malkah’s pride in her creation—something she built to shield her granddaughter, as Avram built Yod to shield Tikva—runs smack up against Shira’s version of how the world is. As does her relationship with Yod, who is like neither her silent, closed-off ex-husband or the ever-performing Gadi. Shira’s work with Yod is for his benefit, but it undoes the programming she gave to herself, freeing her from the limits imposed by the story of Gadi, the story of her controlling corporate job, the story of her old life.

And this, maybe, is where the programming Malkah gives Yod makes him the most human: like Shira, he is able to change himself, to rewrite programs, to find a way around things he learns to fear. He can become someone other than who he was created to be. The tertiary story in Piercy’s novel reflects this work, but on a bigger scale: two other characters subvert expectations of motherhood, destruction, and rebuilding, working to rewrite the world’s story by putting narrative power back into the hands of people rather than corporations.

Yod is a person, and he has control of his own narrative, but he also completes his programming. The two things can’t be pulled apart, only reshaped, reformed, changed. What he wants is not what his creator and his world, want for him, and in that tension, he finds his own story. If a cyborg can reprogram himself, so can we all. Under the guise of a taut, thoughtful cyberpunk thriller, Piercy explores the stories that make us who and what we are—and the possibility that we can all change if we tell ourselves new stories, find new programs, value new ways to be.

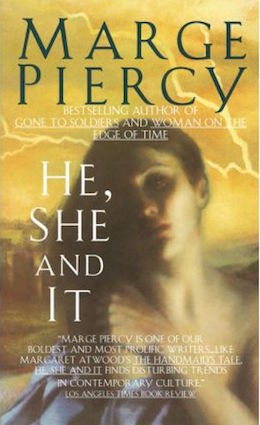

Molly Templeton wishes this book had a better cover, so more people might be inspired to pick it up at random.