A few months ago, I turned pro.

By “turned pro,” I mean that I got my novel picked up by one of the major publishing houses in a three-book deal.

I don’t want to overstate what that means. It’s the first step on a long road, and future sales and the conditions of the marketplace may consign me to the remainder rack quicker than you can say “Myke who?”

But it is, for me (and I suspect for most aspiring writers) the main line I sought to cross making the majors, getting picked for the starting lineup.

Put me in coach, I’m ready to play.

Like most of the folks reading this, I was serious and committed, pushing hard for years (all my life dreaming about it, fifteen years seriously pursuing it) with little movement. When I was on the other side of that pane, trying desperately to figure a way in, I grasped at anything I could, looking for the magic formula.

There isn’t one, of course, and everyone told me that, but I never stopped looking.

Now, having reached that major milestone (with so much further to go), I sit and consider what it was that finally put me over the top. Because the truth is that something clicked in the winter of 2008. I sat in Camp Liberty, Baghdad, watching my beloved Coast Guards march past Obama’s inaugural podium on the big screen, and felt it click.

I bitched and whined to anyone who would listen about how unfair life was, about how I just wanted a chance to get my work before an audience, but I knew in my bones that I’d crossed some line. Somehow, going forward, things would be different.

I’ve thought a lot about that time, that shift, and I think I’ve finally put my finger on what changed. The near audible click I heard was my experience in the US military surfacing, breaking the thin skin of ice it had been gathering against for so long. The guy who landed back in the states was different from the one who left. He could sell a book.

We’re all different. We all come at our goals from different angles. I can’t promise that what’s worked for me will work for anyone else. But before I went pro, I wanted to hear what worked for others. I offer this in that same spirit. So, I’ll give you the BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front) as we say in the service: You want to be successful in writing and in life?

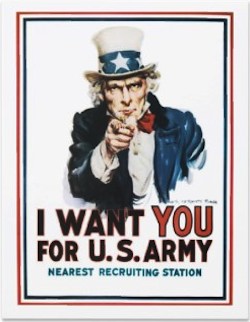

Run, do not walk, to your nearest recruiting station and join up.

I’m not kidding.

Let’s put aside the practical benefits that seem tailor made for the full time writer. Forget the fact that I get full coverage health insurance for $50 a month. Never mind the fact that I get discounts on everything from housing to travel to food to buying cars and cell phone plans. Pay no attention to commissary and gym privileges on any base in the country.

My experience in the military (as a contractor, paramilitary civilian and a uniformed officer) facilitated my writing in three important ways: It taught me the value of misery, it made me focus on quantifiable results, and it made me hungry for challenges, the more seemingly impossible, the better.

Are you sitting comfortably? That might be your problem.

Steven Pressfield is an incredibly successful author. His novel The Legend of Bagger Vance became the film of the same name, and his novel Gates of Fire is widely thought to be the definitive work of historical fiction on the Battle of Thermopylae. Pressfield also wrote The War of Art, which is the only self-help I’ve ever read worth the paper it was printed on.

In The War of Art, Pressfield talks about his experience as a US Marine and how it helped him succeed as a writer. The greatest thing he learned in the Corps? How to be miserable.

“Marines derive a perverse satisfaction from having colder chow, crappier equipment, and higher casualty rates than any outfit of dogfaces, swab jockeys or flyboys . . . The artist must be like that Marine . . . He has to take pride in being more miserable than any soldier or swabbie or jet jockey. Because this is war, baby. And war is hell.”

The human condition is to seek comfort. We want to be well fed and warm. We want to be approved of and loved. We want things to be easy. When something is rough on you, the natural instinct is to avoid it.

You put your hand on a hot stove, you pull it away. Who volunteers to alternately shiver and boil in a godforsaken desert, showering in dirty water until you have perennial diarrhea? Who volunteers to get shot at? Who volunteers to give up your right to free speech and free association? To live where and how you want? To willfully place yourself at the whim of a rigidly hierarchical bureaucracy?

But ask yourself this: Who volunteers to labor in obscurity for years with only the slimmest chance of success? Who gives up their nights and weekends, dates and parties, for what amounts to a second job that doesn’t pay a dime? Who tolerates humiliation, rejection and desperate loneliness?

Why the hell would anybody ever do that? Because it’s worth it, of course. When you’re standing at attention in your finest at a change of command, when someone shakes your hand on the subway and thanks you for your service, when you look in the eyes of a person and know they’re alive because of you, it’s worth everything you went through and more.

The same is true of writing. When you see your name in print, when someone reacts to your writing in a way you’d never expected, tells you it influenced them, changed them, transported them, inspired them, it’s well worth it.

But that part is fleeting. It’s the misery that endures. I know writers who’ve published a half dozen novels only to be dropped for mid-range sales. Others, despite dazzling popularity, couldn’t make enough to keep a roof over their heads. I’ve seen commitment to the discipline wreck friendships, marriages, minds. There are dazzling moments, to be sure, as clear and glorious as when the battalion CO pins the commendation on your chest in front of your whole family.

But it’s as brief and fleeting as that, and before you know it, it’s back to the mud and the screaming and the hard calls with no time to think it through. You have to love that mud. It has to define you. You have to be proud to be covered in it. You have to want it bad enough that you can override your desire to seek comfort. When there’s work to be done, you don’t call your friends to go out to drink and bitch. Instead, you sit down and work.

Because if it ain’t rainin’, you ain’t trainin’, and you love that mud. Because you’re a damned marine.

Oorah.

My point is this. Uncomfortable? Miserable? Wondering why you bother?

Glad to hear it.

Because you’re exactly where you need to be. The fire that’s burning you is the crucible where the iron is forged. I can’t promise you that it’ll hold up under the repeated blows waiting for it when it emerges, but there’s only one way to find out.

This is the chief reason I have avoided writing groups and online workshops. There’s a lot of great advice to be had in them, but the temptation to use them as group therapy is strong. In my floundering days, I spent a lot of time seeking ways to comfort myself in the face of the seeming impossibility of writing success. Instead of using fellow writers as sounding boards for questions of craft, I leaned on them to share dreams and pains, to know that I wasn’t alone in my loneliness and fear of failure.

And that’s not going to get you where you need to go. Work will. You relieve the discomfort (usually at the expense of work) and you take yourself out of the zone where your best work is performed and spend precious time that could be dedicated to honing your craft.

Remember Pressfield’s point. This is war. It’s not supposed to be a picnic.

This post originally appeared on John Mierau’s blog, here.

Myke Cole is the author of the military fantasy Shadow Ops series. The first novel, Control Point, is coming from Ace in February 2012.