“Better a storm crow than a carrion bird.”

–Range of Ghosts, Elizabeth Bear

This is not a review. The Powers That Be here at Tor.com have asked me to write about Elizabeth Bear’s Eternal Sky trilogy as a whole now that it’s available in its entirety for your reading pleasure. Because I love it, you see. I love it so much, now that it is done, that the small criticisms I may have had for the middle book fade into insignificance: it has the kind of conclusion that raises up everything that has gone before, that adds fresh meanings to previous events in the light of new knowledge, new developments, new triumphs and griefs.

I will tell you what I did, when I reached the final page of Steles of the Sky and closed its covers and recovered my emotional balance long enough to stop weeping.

I went looking for music. Not just any music, but music that recalled the sweep and scale of the steppes and the world of the Eternal Sky. It seems inevitable that I should’ve ended up listening to traditional Mongolian music, given the debt that the Qersnyk in Bear’s trilogy owe to Mongolian culture—but this marks the first time I can remember that a novel set in a fantasy world has prompted me to seek out music and art from the cultures that influenced its creation. Because the world that Bear’s created here, in its depth and detail and richness and possibilities, makes me want to know more both about it, and about its influences: it invites its readers to think on broader, stranger, vaster canvases than those to which they’re accustomed.

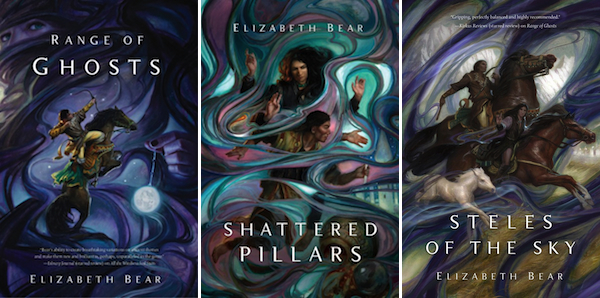

Talking about something one loves deeply, as a critic or a reviewer, involves making oneself vulnerable. It is always easier to discuss something’s flaws, its technical successes and failures, than it is to talk about the intensely personal impact of the emotional reaction it evokes. When it comes to Elizabeth Bear’s Eternal Sky trilogy, that emotional reaction strikes me extremely hard. Range of Ghosts, Shattered Pillars, and Steles of the Sky comprise, as a unity, the most powerful story I’ve read in years: a story that subverts the expectations of epic fantasy even as it uses them to create a narrative with mythic resonance and force. I read Range of Ghosts two years ago, and it felt to me like the epic fantasy I’d spent my whole life waiting to read: waiting without ever knowing what precisely I was missing.

Epic fantasy has long been dominated by Tolkien and his inheritors. In recent years epic has come to be represented in the wider sphere by Crapsack World deconstructions of heroes and heroic arcs, in a retreat towards a grim and grey sort of “realism” that deprives fantasy of much of the element of wonder that makes it fantastical. But the Eternal Sky trilogy sidesteps both of these tendencies to go its own way: a way filled with wonder, amazing world-building, heroism and tragedy—and also filled with grit, emotional realism, and a light, ironic, humane sense of humour.

And mythic grandeur: Lee Mandelo said it best in her review of Steles of the Sky:

“[T]he centrality of the mythic, the real import of religion and faith in this novels [is] what makes them stand out as far and above the most fascinating and true-to-label ”epic“ fantasies I’ve read in recent years. These novels recall legends; rather than backgrounding religion as merely part of the landscape, Bear’s Eternal Sky books present genuine and world-structuring (literally) conflicts between religions—none of which are more or less concrete than the others. This interrelation of faiths, of figures and gods and divinities, is the source of much of the power of the climax and denouement of Steles of the Sky.”

Bear sets her trilogy in a world inspired by Central Asia and the Silk Road, by the Chinese kingdoms and Tibet and the Mongolian steppe and the caliphates of Turkey and Iran. The scope of the story stretches the length of a continent, and the peoples of the Celadon Highway and the wider world are varied, diverse, vibrant, and rarely predictable: from the Lizard Folk with their woman-king to an all-female order of scholar-priests in the Uthman Caliphate; from the deadly suns of Erem to the city of Tsarepheth in the lee of a dormant volcano. There are megafauna and ghulim, intelligent bear-people and intriguing tiger-people (the Cho-tse) with complicated relationships to their god. There are dragons and treaties and sacred horses, curses and wizardry and demons, loyalty and treachery, plague and war, love and death.

The trilogy opens with vultures, and it ends with them, too.

The prose is honed, lustrous, precise and pointed as a knife-blade. If it weren’t so sharply visceral, I’d call it “polished” or “elegant,” but it has violence as well as grace. Chiselled, perhaps, is one word for it: it draws me back and sweeps me along with it every time I open a page. It doesn’t efface itself, and I love it for its descriptive brilliance.

But most of all I love this trilogy for its characters. Its many, many characters, all of whom, even the antagonists, feel like real people with real motivations and desires and complexities. Temur, heir to the Great Khagan, hunted by assassins, determined to find Edene, the woman he promised to marry; Samarkar-la, who gave up her position as the elder sister of the Rasan emperor for the chance to have power in her own right as a wizard; Edene, who escapes from captivity to raise an army from the ruins of deadly Erem; Hong-la and Tsering-la, wizards of Tsarepheth who struggle to treat demonic plague and protect refugees; Brother Hsiung and the Cho-tse Hrahima, Temur and Samarkar’s travelling companions. More, many more, all with their own histories and heroisms and regrets.

Saadet, who shares her body with the spirit of her twin brother after he dies, who has vowed vengeance on Temur; Ümmühan, the slave poetess and scholar whose songs and betrayals topple caliphs and affect the fate of armies.

I loved, towards the end of Steles of the Sky, that—reunited—Edene and Temur and Samarkar make a family unit, a political unit, that’s stronger together than it is apart; that Samarkar and Edene’s friendship is fledgling but real. I loved the presence of gods and goddesses, of dragons bound by treaty and battles in the sky, of Samarkar saying “I had an itch in my religion,” and Temur making his great, his terrible, his inevitable bargain with Mother Night.

I don’t have words to express how much, and how deeply, this trilogy affected me. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to go start reading Range of Ghosts again.

Range of Ghosts, Shattered Pillars, and Steles of the Sky are available now.

Read excerpts from all three novels (and other works by Elizabeth Bear) here on Tor.com

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. Her blog. Her Twitter.