In many ways, the 1970s were the first golden age of superheroes on TV. You had Wonder Woman and The Incredible Hulk, not to mention stuff like The Six-Million Dollar Man and The Bionic Woman.

In addition, two TV movies were produced as back-door pilots based on Marvel’s heroes Spider-Man and Dr. Strange. The former had been done in animation (complete with iconic theme song), and also in some amusing live-action shorts on the kids show The Electric Company (which was your humble rewatcher’s first exposure to the character), while the 1978 TV movie was the sorcerer supreme’s first time being adapted into another medium.

Both, unfortunately, share issues with pacing and with grokking the source material.

“That character in the clown suit, he worked out pretty good”

Spider-Man

Written by Alvin Boretz

Directed by E.W. Swackhamer

Produced by Charles Fries & Daniel R. Goodman

Original release date: September 14, 1977

In a New York City that looks a lot like Los Angeles, a doctor walks out mid-exam without a word, and a lawyer does likewise in the middle of closing arguments. The two of them then rob a bank and crash their getaway car into a brick wall, leaving the pair of them comatose. Two thugs take the money from the car before any emergency services show up.

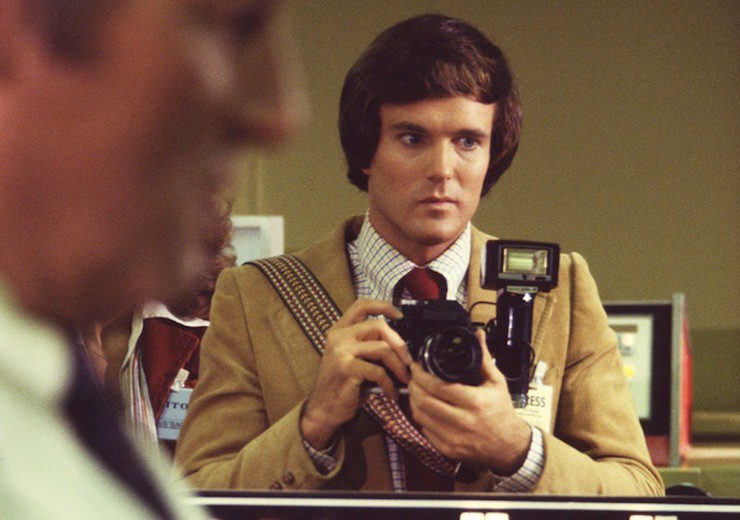

Grad student Peter Parker is trying to sell photos to the Daily Bugle, but J. Jonah Jameson says they’re too arty and not newsworthy. Jameson refuses to send Parker on an assignment—he’s only talking to him because he respects that he’s working his way through college.

Parker goes to his college lab where he and his lab partner Dave are working with radiation. After Parker can’t accept a delivery due to not having the money to pay for it, he and Dave continue their experiment, during which a spider gets into the radioactive chamber. Said spider later bites Parker.

While walking down the street, Parker is pursued by a car down an alley (he senses that the car’s about to hit him before it happens). He leaps out of the way and crawls up the wall, much to his shock. Meantime, the car is driven by a judge who just robbed a bank and crashed the car. Parker was too busy gawping at his newfound powers to notice the two guys who take the money, but he does talk to the cops, including the cigar-chomping Captain Barbera.

Parker experiments with his powers, crawling all over the outside of his house. Miraculously, nobody sees him. He then tries to do it in the middle of town for no compellingly good reason, and he stops a purse-snatching by virtue of scaring the crap out of the thief by crawling on the wall.

Rumors of a “spider-man” spread like wildfire, and when Parker hears from Jameson about said rumors, he says he knows all about the person in question, and he can get pictures. Jameson is dubious.

Parker talked about a costume, so he goes home and somehow sews one. (Where he got the money for the fabric and sewing equipment when he can’t come up with $46 to pay for lab equipment is left as an exercise for the viewer.) He sets up his camera to take photos automatically and brings them to Jameson. While at the Bugle, word comes in of another respected person committing a robbery and slamming his car into a building. No staff photographers are available, so Jameson reluctantly sends Parker.

While there, he uses his spider-strength to free the thief—a professor named Tyler—from being pinned by the steering wheel, then he offers to give Tyler’s daughter Judy a lift to the hospital. Unfortunately, the EMTs bump Parker and knock the film out of his camera, exposing it and ruining his pictures.

Tyler has no memory of what happened. Barbera is suspicious of this, and also of Parker just showing up at the last two crime scenes.

Judy says that her father was seeing a self-help guru named Edward Byron, and the two of them go to one of Byron’s meetings, where his notion of self-help is less new-agey and more tough-lovey, as he comes across as a drill sergeant more than a guru. Parker expresses skepticism at the efficacy of Byron’s program and leaves.

However, Byron is using the members of his program. They all get a special lapel pin, and he broadcasts a signal over that pin to control the people. Byron sends a command to Tyler to kill himself before he can tell the police about him, but Spider-Man manages to save him.

Parker creates artificial web shooters in his college lab, er, somehow, and then checks out Byron’s HQ after hours as Spider-Man. He’s met by three Asian guys wielding shinai. Spider-Man beats them mostly by confusing them by crawling on the walls, though they give him a run for his money.

As Parker, he returns to see Byron, saying he wants to give the program a chance. Byron gives him a lapel pin. He goes home and uses his unusually fancy home computer set up (how he can afford this and not be able to pay for his lab equipment remains an exercise for the viewer) to discover the signals Byron is sending out.

Byron gives the mayor an ultimatum—give him $50 million or he’ll make ten people commit suicide. The meet is set up, and ten people—including Parker—prepare to kill themselves. Parker does so by going to the top of the Empire State Building, but the curved, pointed fencing that is there to keep people from doing that very thing pokes Parker’s pin and knocks it off.

Returned to his senses, he goes to Byron’s HQ and trashes the antenna he’s using to broadcast his signal. The three kendo dudes, having already gotten the crap kicked out of them by Spider-Man, let him in without a fight, and Spidey finds Byron being hypnotized by his own beam, since trashing the antenna turned the signal inward, er, somehow. Spider-Man says he should go to police headquarters and turn himself in, which he does. Meantime, Barbera arrests Byron’s two thugs, who give Byron up in a heartbeat (so even if Byron confessing via hypnotic suggestion isn’t considered a viable confession, he’ll probably still go to jail).

Parker gives Jameson pictures of Spider-Man with the three kendo dudes and goes off with Judy hand in hand.

“I am several hundred years too old to be all right”

Dr. Strange

Written, produced, & directed by Philip DeGuere

Original release date: September 6, 1978

The Nameless One approaches Morgan Le Fay—who has been trapped for hundreds of years by the sorcerer supreme, who goes by the name of James Lindmer—and gives her three days to kill either Lindmer, whose powers are waning, or his successor, if he winds up passing on the mantle before Morgan can get to him.

Morgan and her prominent cleavage both agree readily and they come to Earth. Morgan takes possession of a college student named Clea Lake and has her push Lindmer over a railing onto the street. However, he is still a strong enough sorcerer to heal himself and he walks away.

Clea continues to see Morgan in mirrors and have nightmares and such. For his part, Lindmer has his acolyte, Wong, seek out Dr. Stephen Strange, who is destined to be his successor.

Waking from a nightmare, Clea sleepwalks and is almost hit by a cab. She’s taken to East Side Hospital, where she’s put in the care of Strange. She has forgotten who she is, and she didn’t take her purse with her. She’s also deathly afraid to go to sleep. (Strange refuses to prescribe meds for her, but the head nurse tries to dispense them anyhow, as that’s SOP, which leads to Strange and the hospital administrator butting heads.)

Lindmer comes to the hospital to check on Clea—using his magic to coerce people into letting him into places, which isn’t very heroic, but whatever—and he also talks to Strange for a bit, giving him a business card that has a logo that matches the design on the ring that Strange wears. Said ring was willed to him by his father—both his parents died in a car crash when Strange was eighteen—and he’s never taken it off.

Clea is given thorazine so she can sleep by the administrator, and she lapses into a coma. Strange goes to Lindmer in the hopes that he can help her, and Lindmer shows him how to release his astral form. The astral realm is where Clea’s spirit has gone, and Lindmer teaches Strange a simple spell to cast if he meets resistance. (He does, he invokes it, the problem goes away. Cha cha cha.)

Despite having traveled to an astral realm to rescue a comatose woman from a demon, Strange is skeptical about this world of magic (dude, seriously?) and he rejects Lindmer’s offer to take up the mantle of sorcerer supreme.

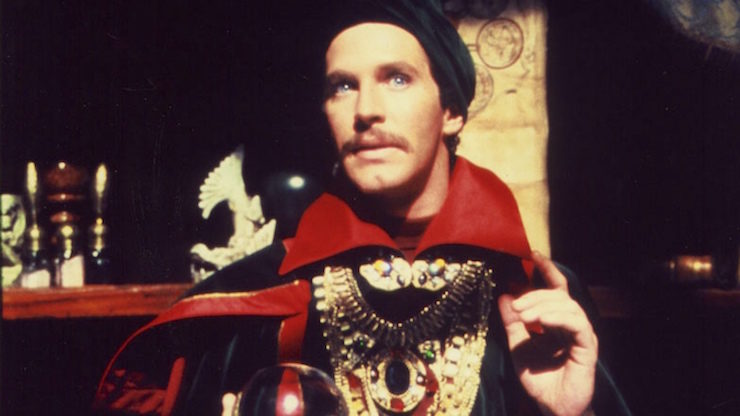

Morgan manages to penetrate the wards of Lindmer’s home (thanks to unwitting aid from Strange and a cat) and entraps both Lindmer and Wong. She then possesses Clea while she and Strange are on a date and Morgan tries to seduce Strange (both literally and figuratively), including putting him in an outfit very similar to what he wears in the comics. However, while Strange is initially entranced by her slinky red dress and mighty mighty cleavage, he eventually refuses her (after making sure to give her a smooch first). Lindmer reveals that he let Morgan trap him so that Strange could see for himself what the stakes are.

Strange stops Morgan, and the Nameless One punishes her.

Clea has no memory of what happened, and when she’s released, she and Strange have the exact same conversation they’d had previously about whether or not to go out on a date, which is only a little creepy, and Strange agrees to become sorcerer supreme—though he apparently doesn’t give up his day job. Even as the Ancient One passes Lindmer’s power onto him and gives him a doofy purple outfit with a bright yellow starburst (which looks nothing like what he wears in the comics, and also, ew), he still keeps his gig at the hospital.

And then he and Clea see Morgan pushing a self-help program.

“Ignorance has been a kind of protection for you”

Both these movies were back-door pilots, but only one led to a series. Spider-Man had two abbreviated seasons from 1978-1979. Dr. Strange was not picked up.

The two movies share a great deal in common. They both take place in New York City, but are very obviously primarily filmed in Los Angeles. (Seriously, the two cities look nothing alike, why do people keep insisting on trying to make L.A. look like NYC?) At least they filmed at the actual Empire State Building for Parker’s almost-suicide, and Dr. Strange makes good use of second-unit photography to disguise itself as being in New York better than Spider-Man does.

They both have leads who have a certain charm, but it’s very low-key, and results in them leaving much less of an impression than they should.

But most of all, both films show only a cursory understanding of the source material, and simplify the storylines a little too much. Both characters have strong origin stories in the comics, and both origins are utterly botched here.

In the comics, the main reason why Parker decides to use his powers to fight crime is because his inaction leads to the death of his uncle Ben. In the movie, he has no such motivation, and he only seems to create the costume because he word-vomitted in Jameson’s office and somehow talked himself into the costume. But he has no reason to actually become a crime-fighter except that it’s because the script calls for it. The creation of the web-shooters is also given absolutely no explanation.

Similarly, in the comics, Strange is indeed a doctor, and an arrogant sumbitch he is, until an accident costs him the use of his hands. No longer able to do surgery, he travels to the East to find a guru who will heal him, and finds more than he bargained for. In the movie, Strange is a lothario, but actually a decent sort (mostly), and he was destined from jump to become a sorcerer.

In each case, the adaptation removes any sense of character journey. Instead of a Peter Parker who is a nerd who is picked on by other kids, and who sees being a hero as a release, a way to become what puny Parker never could be, we just get an ordinary-ish grad student who is struggling to make ends meet. Instead of a kid who gets heady with power and then has a comeuppance when his newfound arrogance gets his father-figure killed, we just get a guy who gets powers and, uh, becomes a superhero and stuff.

Strange doesn’t go through any real changes. His world changes around him, but he’s still the same guy at the end that he is at the beginning, except now he has powers and an awful costume.

On top of that, both movies have pacing issues. Dr. Strange isn’t too bad in that regard, but Spider-Man is almost disastrous in its first half hour, as we spend way too much time watching Parker and his lab partner play with radiation, and the spider getting irradiated, and then Parker getting his powers, and then him taking a nap and dreaming about what happened so we can watch it all over again, and make it stop already!

Plot issues up the kazoo here, too. Why does Morgan only have three days to stop Lindmer? Byron is moving quickly because he doesn’t want the police to figure out that all the robbers are part of his program, but the cops never even come close to the possibility of figuring that out. (Then again, Barbera and Monahan mostly just stand around and make snarky comments. At no point are either of them ever seen to be doing much by way of policework.) Why does Lindmer let himself be captured by Morgan? How is it that Parker can create a costume and web-shooters and has a computer that can detect Byron’s microwave, yet he has to borrow $46 from his new girlfriend?

Hilariously, both have almost interchangeable female leads, as Eddie Benton’s Clea and Lisa Eilbacher’s Judy are both remarkably similar in personality and looks (the former being mostly pretty dull, all told, and mostly you wonder what Parker and Strange see in either of them), and both have our heroes working for old white men who complain a lot and don’t like our heroes very much.

The actors do the best they can with the material. The movie’s Jameson—like everything else—is toned down, but David White does decently with it anyhow. (I love him asking if he can step on Spider-Man the way he would a spider.) Michael Pataki is fun as the cigar-chomping Barbera, Hilly Hicks has a relaxed charm as Robbie Robertson, and it’s amusing to see Robert Hastings—the voice of Commissioner Gordon in Batman: The Animated Series in the 1990s—as a cop. Nobody ever went wrong casting Clyde Kusatsu or Jessica Walter in anything. The former’s Wong is more assistant and helper than the stereotypical manservant he was in the comics, and the latter manages to rise above the rather risible writing of her character to be genuinely seductive and menacing. And hey, that’s Michael Ansara as the voice of the Ancient One!

Ultimately, though, these movies are much like the main characters: affable, but less than they could be.

They were not the only characters to be adapted in this era, though. Both Captain America and Howard the Duck had their turns in the sun, the former on television, the latter on the big screen. We’ll look at them next week.

Keith R.A. DeCandido is not ready for prime time.