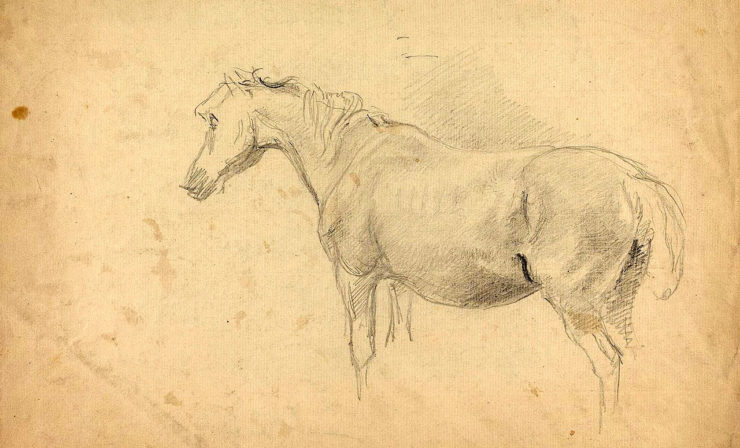

Recently on Twitter, one of the artists I’ve followed for years—since Livejournal, in fact—joined a thread of other artists, all sharing a phenomenon that is apparently common in the visual arts. It’s called “the mind horse.” The challenge is to draw without a reference, and the principle is that every artist has a horse in their mind, that they will revert to when asked to draw a horse. The kicker is that that horse almost never resembles the real thing.

Or does it?

This thread pings my mind in so many different directions. Visual: how hard it really is to draw an accurate portrait of anything, and how many different ways it’s possible to get a horse wrong. What the individual eye sees when it looks at a horse. Size and mass. Shapes: the oblong of the head, the ellipse of the body, the straight lines of the legs. Ears at the top. Mane. Tail.

Poses. Every artist has iconic positions. Standing with head up and mane blowing in the wind. Slouching in a back pasture. Performing in some way, with or without a human in the frame.

Drama. Running, racing. Rearing. Prancing.

Glimpses. A head, a flag of tail. A hoof. A nose. An eye. The big liquid eye of the horse that draws the observer in, like a gate into a dark and gleaming world.

Every artist, in every medium, has their own style, their own preferred tropes and habitual themes. Some of them solidify into a cultural standard, like Hollywood perceptions of the horse. The Hollywood horse always rears. They make constant whinnying noises. They gallop everywhere, and when they stop, they rear. And whinny.

The Hollywood horse is a mind horse. It’s a sketch, a shorthand. A handful of behaviors that creates the impression of Horse. Even in films and series that purport to be about or focused on horses, this shorthand persists, regardless of how factually incorrect it is. It’s myth that perseveres because it’s easy and simple and viewers are conditioned to accept it.

Writers have a whole universe of mind horses. Tropes and themes that they revisit over and over, examine and reexamine in work after work. Assumptions—personal or cultural—that inform their plots and characters and settings. They’re labor savers when they work, and traps when they don’t. The hard part is knowing which is which.

With horses at least, it’s fairly easy to get the facts right. There’s a legion of resources online, and horse people as a demographic love to share what they know. So, in their own unique way, do horses themselves.

The more you know about horses, the closer your mind horse comes to the real thing. It’s a blessing, when you think about it—as compared to, say, the mind novel that you’re trying to write, versus the on-the-page kludge that you keep getting left with. Horses are solid and concrete and consensually real. You can point to the one in the pasture and say, “Horse.” And people will acknowledge that yes, that’s a horse, all right.

The other kind of mind horse, the horse of the mind, is a little more complex. That’s the horse as they are in their essence—as a twitter commenter observed, quoting Terry Pratchett, “Taint what a horse looks like, it’s what a horse be.” That’s the essence of the beast, what makes it a horse, even before you see the four hooves and the mane and the tail.

For the writer, that’s the real challenge. To write well enough and believably enough that the casual reader will accept the horse as it is, and the expert will allow as how, hm, not bad, can’t quibble that too much. The well-written horse satisfies both ends of the spectrum—and can do it in a handful of well-chosen words, just as an artist can embody Horse in a single well-drawn line.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.