The cold equations of “realism,” some claim, suggest there is little scope for women taking an active and interesting role in epic stories set in fantasy worlds based in a pre-modern era. Women’s lives in the past were limited, constrained, and passive, they say. To include multiple female characters in dynamic roles is to be in thrall to quotas, anachronisms, Political Correctness, and the sad spectacle and dread hyenas of wish-fulfillment.

Is this true?

Let’s leave aside the argument that, in fantasy, if you’re going to include dragons you can also plausibly include women in a range of roles. That’s absolutely correct, although it veers uncomfortably close to equating women’s presence in epic narrative to that of mythical creatures. As an argument to include women it’s not even necessary.

Of course there are already many fascinating and memorable female characters in epic fantasy, with more being added every year. So, yes, write women—write people—however you want, with no limits and constraints.

More importantly, any cursory reading of scholarship published in the last fifty years uncovers a plethora of evidence revealing the complexity and diversity of women’s lives in past eras and across geographical and cultural regions.

I’m not suggesting the legal and political situation of women has been universally equal to that of men across world history, much less equivalent in every culture. And this essay is not meant to represent a comprehensive examination of women’s lives (or what it means to be called a woman) in the past, present, or cross-culturally. Far from it: This represents the merest fractional fragment of a starting point.

My goal is to crack open a few windows onto the incredible variety of lives lived in the past. How can women characters fit in epic fantasy settings based on a quasi-historical past? How can their stories believably and interestingly intersect with and/or be part of a large canvas? You can model actual lives women lived, not tired clichés.

Here, mostly pulled at random out of books I have on my shelves, are examples that can inspire any writer to think about how women can be realistically portrayed in fantasy novels. One needn’t imitate these particular examples in lockstep but rather see them as stepping stones into many different roles, large and small, that any character (of whatever gender) can play in a story.

Hierarchy, Gender, and Stereotype

No other society now or in the past holds to the exact same gender roles as modern middle class Anglo-American culture. Gender roles and gender divisions of labor can vary wildly between and within cultures. For example, textile work like weaving and sewing may be seen as a domestic and thus womanly occupation, or it may be work men do professionally.

In addition, many societies hold space for and recognize people who do not fit into a strict gender binary. Genderqueer and transgender aren’t modern Western ideas; they are indigenous, include third gender and two-spirit, and can be found all around the world and throughout the past. Sexuality and gender may be seen as fluid rather than fixed, as variable and complex rather than monolithic and singular.

Don’t assume gender trumps every other form of status in the division of social power and authority.

Among the Taíno, “Name and status were inherited from one’s mother, and social standing was reckoned such that women might outrank men, even if men usually held political power.” [Fatima Bercht, Estrellita Brodsky, John Alan Farmer, and Dicey Taylor, editors, Taíno: Pre-Columbian Art and Culture from the Caribbean, The Monacelli Press, 1997, p. 46]

Sarah B. Pomeroy writes “In the earliest Greek societies, as known through epic, the principal distinction was between aristocrats and commoners. Thus, the hero Odysseus rebukes a common soldier, Thersites, for daring to speak up to his social superiors, whereas he treats his wife Penelope as his equal.” She contrasts this with the Classical democratic polis in which “all male citizens were equal, but […] the husband ruled the wife and children.” [Sarah B. Pomeroy, Women in Hellenistic Egypt, Wayne State University Press, 1990, p 41]

Furthermore, while the culture of Athens is often taken as the standard among Greeks of the classical era, the situation of women in Sparta at the same time was quite different, notoriously so to the Athenians: Spartan women owned property and managed businesses; daughters inherited together with sons (possibly not a full share); women received education and physical training.

Views of the distinction between public and private spheres play out differently in every society. Modern Western cultural notions aren’t universal.

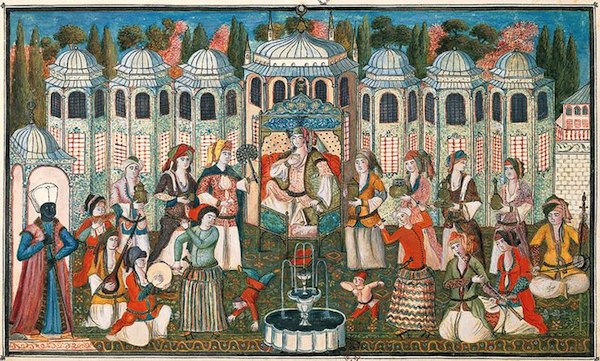

“(I)n the Ottoman case, conventional notions of public and private are not congruent with gender. […] The degree of seclusion from the common gaze served as an index of the status of the man as well as the woman of means. No Ottoman male of rank appeared on the streets without a retinue, just as a woman of standing could maintain her reputation for virtue only if she appeared in public with a cordon of attendants.” [Anne Walthall, editor, Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History, University of California Press, 2008, p 85]

Out-group interactions become even more complicated if people have differing expectations for appropriate or presumed behaviors. For example, if women traditionally own houses and household goods but outsiders see ownership and exchange only in terms of men interacting with men, they may refuse to negotiate with women or be unable to see women as having authority, a situation that happened more than once when Europeans interacted with various Native Americans nations or when outsiders attempted to understand the status of royal women in Genghis Khan’s and other steppe empires.

Remember that across generations a culture can and often does change. Cultures in contact or collision influence each other in ways that may benefit or disadvantage women. People (women as well as men) travel, sometimes of their own volition and sometimes because they have no choice. Cultures, languages, religions, foods, and technologies move with individuals as well as with merchants or armies. Exchange and transmission of ideas can happen in many different and often subtle ways.

Class

Women of lower status rarely appear in the sources that have come down to us (this is true for lower status men as well, of course). A lack of evidence does not mean such women never had interesting or dramatic lives. Many, of course, died young from any number of causes. Many worked brutally hard and were abused throughout often brief lives. But that is never all they were. Rebellion, innovation, success, and ambition can be part of life at every level, and occasionally we find precious glimpses of these usually neglected and forgotten women in the historical record.

American readers are, I hope, familiar with the stories of Harriet Tubman and Ida B. Wells. Both of these remarkable and change-enacting women were born into slavery.

Born in 1811, Fujinami was the daughter of a trooper, and she entered service in the women’s quarters of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1837 as a messenger: “Although messengers ranked so low that they did not have the right of audience with the shogun’s wife, they performed a variety of tasks, some of which could be quite lucrative. They accompanied the elders who acted as the wife’s proxy in making pilgrimages within the city and performed low-level chores for the transaction agents. On an everyday level, they served in the guard office, took charge of opening and shutting the locked door between the women’s quarters and the male administrative offices, negotiated with male officials, and guided visitors to various reception rooms.” [Walthall, p 178]

In 14th century Norwich, Hawisia Mone became part of the Lollard movement, declared heretical by the church for (among other things) its insistence on the equality of men and women. Her existence is known to us because, after her arrest, the church recorded her adjuration of her beliefs, which, even as she is forced to recant, suggest a questing, inquiring, and radical mind: “every man and every woman being in good lyf out of synne is a good prest and hath [as] much poar of God in all thynges as ony prest ordered, be he pope or bisshop.” [Georgi Vasilev, Heresy and the English Reformation, McFarland, 2007, p 50]

“In March 1294, Marie the daughter of Adalasia, with her mother consenting and cooperating, rented herself to Durante the tailor (corduraruis) for three years. Marie was fourteen years old and needed her mother to make this contract legal. […] [She] placed herself in scolarem seu discipulam, as a student, so the emphasis was clearly on education. Marie wanted to acquire the necessary skills to be a seamstress, or her mother wanted this for her. Durante and his wife [although nameless, the wife is treated in the contract as an active partner in the craft] agreed to teach her the craft, feed and clothe her, and keep her in sickness or in health, and in return for all of this teaching and food, they expected one livre for at least the first year.” [Steven A. Epstein, Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991, p 77]

Epstein goes on to add: “Most guilds seem not to have prevented their members from taking on female apprentices, despite the potential problems of mature women exercising their skills without being a member of the guild.”

Law

It’s easy to talk about the legal disabilities women often labored under (and still labor under), and these are very real and very debilitating. But it is also important to understand that people find ways to get around the law. Additionally, not all legal traditions pertaining to women match those of Classical Athens or early Victorian England. “Modern innovations” are not necessarily modern. Napoleon’s civil code restricted married women’s property rights, for example; so much for his sweeping reforms.

In pharaonic Egypt “married women retained full rights to their own property and could engage in business transactions like money-lending without the need of the husband’s approval. This freedom extended to the ability of either party to terminate a marriage unilaterally, without being required to specify any grounds.” [Jane Rowlandson, editor, Women in Society in Greek and Roman Egypt, Cambridge University Press, 1998. p 156]

In tenth century Saxony there is “plenty of evidence that women accumulated, transmitted and alienated predial estate […] as a matter of course.” [K.J. Leyser, Rule and Conflict in an Early Medieval Society, Blackwell, 1979, p 60]

In medieval Valldigna, Spain, Aixa Glavieta “went to court six times until she forced the Negral family return to her the terrace with two mulberry trees” which the head of the Negral family “had unfairly taken from her for one arrova of linen which she had owed him, although the leaves produced by these two mulberry trees alone (and which he had sold immediately) were more than enough to settle the debt.” [Ferran Garcia-Oliver, The Valley of the Six Mosques: Work and Life in Medieval Valldigna, Brepols, 2011, p 166]

In the medieval Islamic world, “Women appear as both claimants and defendants in cases requiring record and recourse […] Although women were often represented in court or in a business transaction by a proxy or agent, often a male relative of immediate family, they just as often actively participated in these transactions. They appeared in court in person irrespective of the gender of the other participants, in cases which they initiated or in which they themselves appeared as defendants.” [Gavin R. G. Hambly, editor, Women in the Medieval Islamic World, St. Martin’s Press, 1999, p 248-249]

Economy, Trade, and Business

Documents discovered at the ancient site of Niya (in Xinjiang, along the southern rim of the Taklamakan Desert) and dating from circa the 3rd-4th centuries CE give a glimpse into the daily life of that time. Most concern themselves with legal and business transactions.

“Women participated fully in this economy. They initiated transactions, served as witnesses, brought disputes to the attention of officials, and owned land. They could adopt children and give them away, too. One woman put her son up for adoption and received a camel as milk payment. When she discovered that her birth son’s master was treating him as a slave, she took her son back and sued his adoptive father, stipulating that the father henceforth had to treat the boy as his son and not a slave.” [Valerie Hansen, The Silk Road, Oxford University Press, 2012, p 48]

Royal Persian women in the Achaemenid era were well known in ancient times as property holders and estate owners. They maintained and managed workforces, provided rations (including special rations for mothers), and leveraged their wealth to support their own status as well as that of relatives. [Maria Brosius, Women in Ancient Persia, Clarendon, 1996]

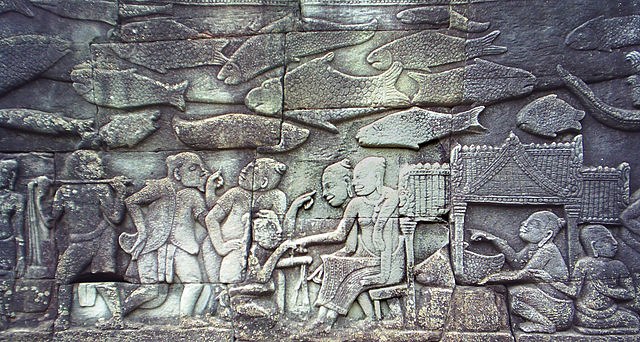

In the late 13th century, Chinese envoy Zhou Daguan visited Angkor in Cambodia, at that time the center of the powerful Khmer Empire. He wrote an account of his travels, including a discussion of trade.

“The local people who know how to trade are all women. So when a Chinese goes to this country, the first thing he must do is take in a woman, partly with a view to profiting from her trading abilities.” [Zhou Daguan (translated by Peter Harris), A Record of Cambodia: The Land and Its People, Silkworm Books, 2007. p 70]

Politics and Diplomacy

If you can’t find numerous examples of women who have ruled nations, principalities, and local polities, you’re not looking hard enough. So instead let’s move on to roles women might play in politics and diplomacy:

“From trade it was not a great step to diplomacy, especially for those who had been both commercial and sexual partners of foreign traders. Such women frequently became fluent in the languages needed in commerce. Thus the first Dutch mission to Cochin-China found that the king dealt with them through a Vietnamese woman who spoke excellent Portuguese and Malay and has long resided in Macao. […] Later the Sultan of Deli, in Sumatra, ordered ‘a most extraordinary and eccentric old woman’ named Che Laut to accompany John Anderson on his embassy to various Sumatran states. She was ‘a prodigy of learning,’ spoke Chinese, Thai, Chuliah, Bengali, and Acehnese and knew the politics of all the Sumatran coastal states intimately.” [Anthony Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce 1450 – 1680, Silkworm Books, 1988. pp 165-166]

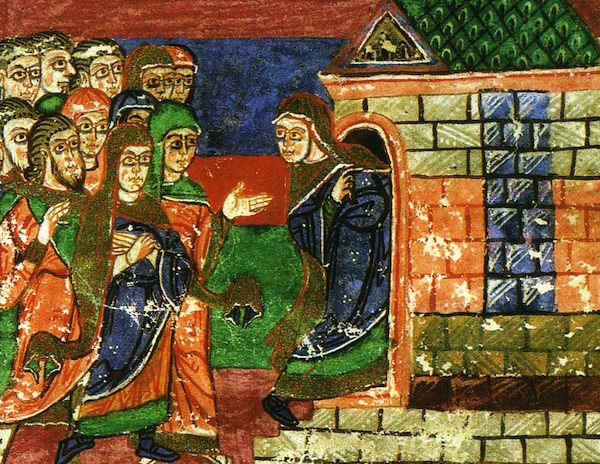

“When the monastery was hallowed, king Wulfhere was there, his brother Aethelred, and his sisters Cyneberg and Cyneswith. […] These are the witnesses who were there, who signed upon Christ’s cross with their fingers and agreed with their tongues. First was king Wulfhere, who first sealed it with his word […] ‘I, king Wulfhere […]’”

There follows a list of the people who witnessed, including, “And we, the king’s sisters, Cyneburg and Cyneswith, we approve and honour it.” [Anne Savage, translator, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, Dorset Press, 1983, pp 48, 50]

“A second misunderstanding of the nature of Ottoman society is the erroneous assumption that the seclusion of women precluded their exercising any influence beyond the walls of the harem or that women were meant to play only a narrow role within the family, subordinate to its male members. […] In a polity such as that of the Ottomans, in which the empire was considered the personal domain of the dynastic family and the empire’s subjects the servants or slaves of the dynasty, it was natural that important women within the dynastic household–particularly the mother of the reigning sultan–would assume legitimate roles of authority in the public sphere.” [Walthall, p. 84]

Marriage

Women who make dynastic marriages can be written as passive pawns, or they can be portrayed as canny political players who function as ambassadors from their birth dynasties to the dynasties they marry into. Genghis Khan’s daughters were married into neighboring tribes and kingdoms but remained at the seat of power as their husbands were sent to war. Authority was left in the daughters’ hands while the men fought and died in the Great Khan’s service—and were replaced by new husbands.

Nor were women isolated once they made diplomatic marriages. It is vanishingly rare for a woman of high birth who is sent to the court of her husband to bide alone in the fashion of a stereotypical ’50s housewife, vacuuming and popping Valium in isolation as a barrage of advertisements remind her that her social capital is measured by the spotlessness of her man’s shirt collars. A woman of high birth in any stratified society will have companions and servants commensurate with her position. They are usually strongly loyal to her because their status rises and falls with hers.

She will also usually retain important ties to her birth family, and will be expected to look after their interests. Stratonice, a daughter of Demetrios Poliorcetes (son of Antigonus the One-Eyed), married first Seleucus and then his son Antiochus (the first and second of the Seleucid emperors). Yet in public inscriptions she emphasizes her role as a royal daughter rather than as a royal wife or mother. She later married one of her daughters to her brother, Antigonus Gonatus, an act that benefited Antigonid authority and power.

If a woman is severed from contact with her family then there can be little benefit in making a marriage alliance. Women forced into an untenable marriage may seek redress or escape. Princess Radegund was one of the last survivors of the Thuringian royal family, which was systemically destroyed by the Merovingian king Clothar in the 6th century. He married her, but after he had her sole surviving brother killed she managed to leave him by fleeing to a convent (and eventually becoming a saint).

The marriage customs and living arrangements of women in lower social strata are not as well known, but one may safely state that they varied widely across time and region. Nuclear families composed of a bride and groom in their own solitary household are rare. Extended families living together have been the norm in many places and eras, and young couples may live with either the groom’s or the bride’s family. Some marriages were arranged while others were made by the participants themselves. Age at marriage varies. The Leave it to Beaver isolate nuclear family often pops up in fiction set in societies where such an arrangement wouldn’t be viable or common.

A note about mothers and sons (and the relationship of young men and old women) and how it can relate to power and trust. In many cases the one person a lord, prince, king, or emperor could absolutely trust was his mother: only she, besides himself, had full investment in his success. If a woman and her son got along and trusted each other, his elevation and his access to power benefited her, and he in turn could benefit from her wholehearted support and from her experience and connections, including to her natal family, whose power and influence were affected by her son’s success.

For example, already in close alliance with his mother, Olympias, Alexander the Great clearly was able and willing to frame political relationships with older women in a similar fashion.

“He appointed [Ada] to the governership of Caria as a whole. This woman was the wife of Hidrieus—and also his sister, a relationship in accordance with Carian custom; Hidrieus on his death-bed had bequeathed her his power, government by women having been a familiar thing in Asia from the time of Semiramis onward. She was subsequently deposed by Pixodarus [and] remained in control of Alinda only, one of the most strongly defended places in Caria, and when Alexander invaded Caria she presented herself before him, surrendered the town, and offered to adopt him as her son. Alexander did not refuse the offer.” [Arrian (translation by Aubrey de Sélincourt), The Campaigns of Alexander, Penguin, 1971, p 90] Recall that Arrian was writing in the second century C.E.

Alexander also captured the household of Persian king Darius III and, besides treating them with respect, folded them into his own household as a way of marking his right to assume the title of Great King in Persia. He famously did not immediately marry or rape Darius’s widow or daughters as a form of “conquest,” but there was one relationship he did care about replicating at once: “Darius’s mother, Sisygambis, was, much more than Ada, treated like a second Olympias.” [Carney, p 93-94]

Such considerations are also true of mothers and daughters. Relationships might be close, or estranged, and certainly high status women and their daughters understood how authority and influence could be enhanced through advantageous political marriages.

“It is surely no coincidence that the most powerful queen mothers [in the Ottoman court] were those with several daughters […] Kösem (1623-52) had at least three […] The queen mother arranged the marriages not only of her own daughters but also of the daughters of her son and his concubines. […] Kösem’s long carer gave her considerable opportunity to forge such alliances. In 1626 or thereabouts she wrote to the grand vizier proposing that he marry one of her daughters: ‘Whenever you’re ready, let me know and I’ll act accordingly. We’ll take care of you right away. I have a princess ready. I’ll do just as I did when I sent out my Fatma.’” [Walthall p 93]

Women could and would defend their daughters when needed:

In 1224 Erard II, “a baron of some importance in southern Champagne […] sold his wife [Emeline]’s dowry for a substantial sum of money, effectively dispossessing his stepdaughter who was in her early twenties and ready for marriage.” Soon afterward Erard seals a legal document in which conditions are clearly laid out requiring him to repay Emeline and to provide a dowry for his stepdaughter, a document which includes contingencies for divorce (presumably if he does not meet his obligations). Emeline herself is supported by her own powerful mother and a brother. [Theodore Evergates, Feudal Society in Medieval France: Documents from the County of Champagne, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993, p 45]

Divorce

The mechanisms and ease of dissolving a marriage vary across eras and regions, and in some situations women had as much (or as little) freedom to divorce as men did, as in the Egyptian example mentioned earlier. Here’s another fascinating example:

“Karaeng Balla-Jawaya […] was born in 1634 to one of the highest Makassar lineages. At the age of thirteen she married Karaeng Bonto-marannu, later to be one of the great Makassar war leaders. At twenty-five she separated from him and soon after married his rival, Karaeng Karunrung, the effective prime minister. At thirty-one she separated from him, perhaps because he was in exile, and two years later married Arung Palakka, who was in the process of conquering her country with Dutch help. At thirty-six she separated from him, and eventually died at eighty-six.” [Reid, pp 152-153]

Note how Reid states that “she separated from him” rather than “he divorced or discarded her,” and note how much that changes how the story is read.

War and Physicality

All too often the sole determiner of whether women “belong” in epic fantasy is whether they took up arms, despite the presence of many menfolk who aren’t warriors or soldiers in historical epics. Kameron Hurley’s essay “We Have Always Fought” comprehensively explodes the idea of women as universal non-combatants. My spouse, an archaeologist with a specialty in militarism and empire, often points out that on frontiers and in revolutions where every body is necessary to success, women step up in diverse ways because that’s what is needed. If women can take on traditionally ‘male’ roles in times of duress then they are, in fact, capable of doing those things at any time. It is cultural pressures that restrict them.

Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire, was famously killed in battle against forces led by Tomyris, queen of the Massagetae.

“The widow of Polypherchon’s son Alexandros—a woman named Kratesipolis—maintained and controlled her late husband’s army, and made successful use of it in the Peloponnese. Her very name, which means “city-conqueror,” may have been adopted by her to commemorate her capture of the city of Sikyon in 314 BC. […] Kratesipolis’s ability to maintain and direct the actions of an army, as well as govern two important Greek cities, demonstrates that she possessed both the resources necessary to employ the soldiers and the authority and respect required to keep under her own control both army and wealth.” [Kyra L. Nourse, Women and the Early Development of Royal Power in the Hellenistic East, dissertation, 2002. pp 214 – 215]

“Cynnane was the daughter of Philip II and his Illyrian wife, Audata. […] [her] mother taught her to be a warrior, and she fought in Philip’s campaigns against the Illyrians. In one of those battles, she not only defeated the enemy but also confronted and killed their queen. [She] would later pass the military training and tradition she had received from her mother on to her own daughter, Adea Eurydice.” [Elizabeth Donnelly Carney, Women and Monarchy in Macedonia, University of Oklahoma Press, 2000, p. 69]

In Vietnam, the famous Trưng sisters led a (briefly) successful rebellion against the Han Chinese. At that time “women in Vietnam could serve as judges, soldiers, and even rulers. They also had equal rights to inherit land and other property.”

Burials of some Sarmatian women (first millennium B.C.E.) include weapons. Although we cannot be sure what the presence of weapons in such graves symbolizes it is common for women in nomadic cultures to ride as well as men and to be able to defend their herds and grazing territories. [See the work of Jeannine Davis-Kimball.]

A Dutch traveler to Southeast Asia remarked on the presence of palace guards who were women: “When the [Mataram] king presided at an official audience he was surrounded by the 150-strong female corps, all carefully selected for their beauty and all skilled in the use of pikes, lances, blowpipes, and muskets.” Later, the Thai kingdom included “a battalion divided into four companies, comprising four hundred women in all. Recruited at the age of thirteen, they served as guards until they reached twenty-five or so, after which time they continued as royal attendants and supervisors. Their leaders were women of proven courage and loyalty handpicked by the king, and the corps itself was a model of organization and military prowess.” [Walthall, pp. 23 & 31]

It was deemed unexceptional in these societies for women to be given weapons-training and employed as palace guards. All-women military companies also appear, for example, in the West African kingdom of Dahomey in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Female athletes are not a creation of the Soviet bloc and Title IX. Among the Taíno there are documented reports of teams of women engaged in a ballgame that was played across the entire region of Mesoamerica. Women from the Santee Sioux, Crow, Hidatsa, Assiniboine, and Omaha nations (as well as others) played a game called shinny, similar to field hockey. Spartan women exercised and engaged in physical contests in a similar manner to Spartan men, to the outrage of the conservative Athenians.

Read the life story of 17th century Frenchwoman Julie D’Abigney, here retold with enthusiasm.

Women’s Work

The most basic division of labor in human society is based on age. Most societies exempt children from work expected of adults, and many skills and professions need years of training (and physical maturity) to attain competence.

Many societies see the tasks necessary to creating community as gendered:

“[In the world of the Hodenosaunee] each person, man and woman, had an important function. Men were hunters and warriors, providers and protectors of the community. Women owned the houses, gathered wild foods, cooked, made baskets and clothing, and cared for the children. Spiritual life […] included a priesthood of men and women Keepers of the Faith who supervised religious rites and various secret organizations that performed curing and other ceremonies.” [Alvin M. Josephy, 500 Nations, Knopf, 1994, p 47]

“Generally, several male smiths in a town will work iron and wood, while at least one female member of the family will work clay.” [Patrick R. McNaughton, The Mande Blacksmiths, Indiana University Press, 1993, p 22]

But gender division may not correspond to modern American stereotypes nor to quaint Victorian notions of feminine daintiness and frailty (however patriarchal the society may be).

“Until the mid- to late-nineteenth century, almost everywhere in France, at least half the people working in the open air were women. […] women ploughed, sowed, reaped, winnowed, threshed, gleaned and gathered firewood, tended the animals, fed it to the men and children, kept house […] and gave birth. Housekeeping was the least of their labours. […] All along the Atlantic coast, women were seen ploughing the fields, slaughtering animals and sawing wood while men stretched out on piles of heather in the sun. In the Auvergne, in order to clear the snow, milk the cows, feed the pig, fetch the water, make the cheese, peel and boil the chestnuts and spin the cloth, women rose earlier and went to bed later than men […] At Granville on the Cotentin peninsula, women fished, repaired boats and worked as stevedores and carpenters. In the Alps they were yoked to asses and hitched to ploughs, and sometimes lent to other farmers.” [Graham Robb, The Discovery of France: A Historical Geography, Norton, 2007, pp 103-104]

Acting as merchants as well as selling and buying in the market is typical women’s work in many cultures while in some cultures women engage in business through male intermediaries. Women in agricultural communities often barter or trade on the side. Who controlled these earnings varies from culture to culture.

Hebrew financial ledgers from medieval Spain include ledgers belonging to women, “and include lists of loans and properties […] [Two of the women who have ledgers] appear as widows engaged in managing the extensive business dealings of their deceased husbands, but the very fact that they managed substantial financial estates indicates that this was an accepted phenomenon, and speaks of their own status.” [Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe, Brandeis University Press, 2004, p 111]

“By the Ur III period [21st century B.C.E.], large numbers of women and girls were working in temple and palace workshops as weavers, producing a great variety of different textiles which were traded widely as well as supplying the needs of the temple itself.” [Harriett Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p 160]

Cooking is a classic example of women’s work often treated as too mundane to be worthy of epic (unless it is performed by a male chef). Dismissing the seemingly ordinary daily chore of cooking ignores its foundational role as a means by which life and strength is perpetuated as well as a skill that may be respected and celebrated.

Now five score wives had Susu Mountain Sumamuru,

One hundred wives had he.

His nephew, Fa-Koli, had but one,

And Sumamuru, five score!When a hundred bowls they would cook

To make the warriors’ meal,

Fa-Koli’s wife alone would one hundred cook

To make the warriors’ meal.

In the annotation to these lines, the translator notes what is implied in the text and would be understood to the audience: “Fa-Koli’s wife [Keleya Konkon] is a powerful sorceress.”

The ability to feed people is not trivial but powerful.

[Fa-Digi Sisòkò, translated and notes by John William Johnson, The Epic of Son-Jara, Indiana University Press, 1992, p 93 & 138]

Health, Life Expectancy, and the Role of Women in Medicine

In 1999 I attended an exhibit on “the Viking Age” at the Danish National Museum. As you entered the exhibit room you immediately faced a row of skeletons placed one next to the other to compare height and robustness. Demographers had measured average height by examining burials from the Neolithic through the 20th century. The height of the skeleton representing the early Middle Ages (10th century) almost matched the height of the skeleton representing the 20th century. Height declined after the 12th century, and the shortest, least robust skeletons came from the 17th and 18th centuries. It turns out that, in this region, health and nutrition were better in the so-called Dark Ages than at any other time up until the present.

Demographics can turn up other unexpected localized features:

“There is however one demographic feature to be observed in early Saxon aristocratic society which can be traced more clearly—the respective expectations of life for adult men and women. In collecting materials for the history of the leading kins in the tenth and early eleventh centuries, it would be difficult and rather purblind not to notice the surprising number of matrons who outlive their husbands, sometimes by several decades and sometimes more than one, their brothers and even their sons.” [Leyser, p 52]

Although she lived slightly later, imagine the iron-willed Eleanor of Aquitaine who in her late 70s twice crossed the Pyrenees first to collect a granddaughter and then to escort young Blanche to her affianced husband-to-be, the heir to the throne of France. Women weren’t “old at 30,” and despite high rates of mortality in childbirth (and all the other sources of mortality that plagued the world then and in all too many areas still do now) some lived to a reasonable age even by modern standards.

Of course health and hygiene vary tremendously worldwide.

“If Southeast Asians [in the 14th-17th centuries] also lived longer than Renaissance Europeans, as seems likely, one important reason may have been a lower child mortality. […] The relatively good health of Southeast Asians in the age of commerce should not surprise us if we compare their diet, medicine, and hygiene with those of contemporary Europeans. For the great majority of Southeast Asians serious hunger or malnutrition was never a danger. The basic daily adult requirement of one kati [625 grams] of rice a day was not difficult to produce in the country or to buy in the city. […] The care of the body, the washing and perfuming of the hair, a pleasant odour of the breath and the body, and neatness and elegance in dress were all matters of great importance […]” [Reid. p. 50]

“The Japanese lifestyle was also healthful because it was hygienic, certainly compared to either Europe or the U.S. in the mid-nineteenth century. Bathing was a regular part of life by this time, people customarily drank their water boiled in the form of tea, and they carefully collected their bodily wastes to be used as fertilizer.” [Susan B. Hanley, Everyday Things in Premodern Japan, University of California Press, 1997, p 22]

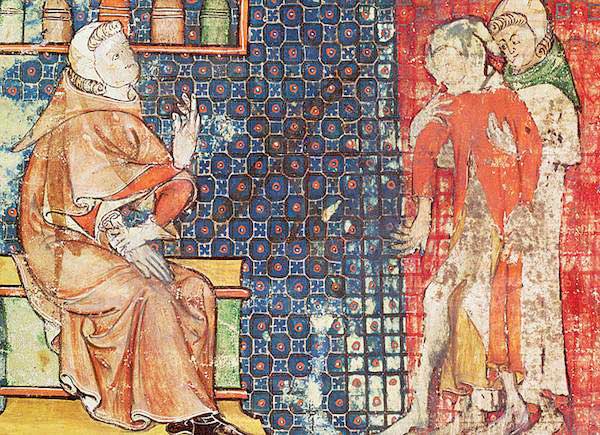

Women were not universally passive recipients of male medical knowledge nor were they always dependent on male expertise and institutions. In the medieval Islamic world women appear in the historical record as doctors, surgeons, midwives, and healers, and well-to-do women in the Islamic world appear as patrons of hospitals and charities, especially those that benefit poor women. In the 12th century in the Holy Roman Empire, abbess Hildegard of Bingen wrote copiously about spiritual visions and about music, and her writing included the scientific and medical works Physica and Causae et curae. She also corresponded with magnates and lesser people from all over Europe, made three preaching tours, and defied the abbot who ruled over her convent by absconding with some of the nuns to set up a new convent in a place of her choosing.

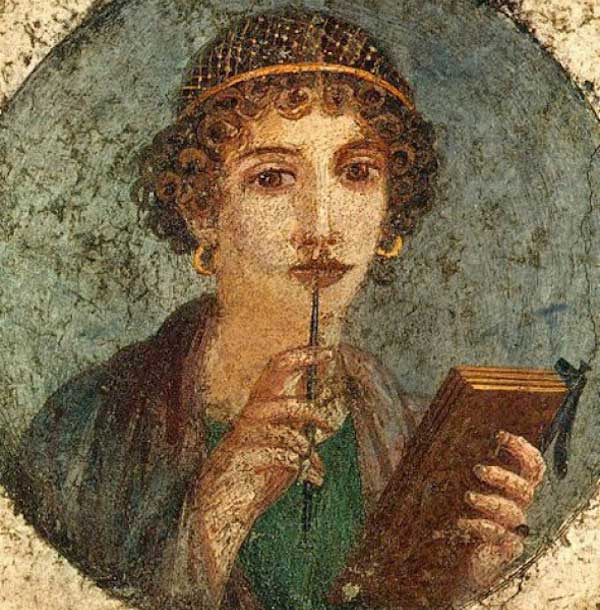

Education and Literacy

We’re all familiar with stories where the son gets thorough schooling while his sister is not even taught to read because it’s not a skill that’s valued in a bride. But many women throughout history were educated, and not every culture has seen literacy as a “male” virtue.

Enheduanna, the daughter of Sargon of Akkad, was a high priestess (an important political position) and a composer and writer of religious hymns that remained known and in use for centuries after her death (23rd century B.C.E.)

In the second century B.C.E. a certain Polythroos son of Onesimos made a gift to the city of Teos to use for educating its children, including “three grammar-masters to teach the boys and the girls.” [Roger S Bagnall and Peter Derow, editors, The Hellenistic Period: Historical Sources in Translation, Blackwell Publishing, 2004, p 132]

“Since the beginning of the Safavid period, the art of reading and writing, calligraphy, and composing letters was common among the women of the court, who used it for personal correspondence as well as for diplomatic activities.” [Hambly, p 329]

16th century Nuremburg midwives seem to have commonly been given printed copies of their oath and of baptism regulations, suggesting it was expected for them to be literate. A manual called “The rosegarden for midwives and pregnant women” was in popular use, and the knowledge midwives had in these circumstances would have been similar to that of physicians of the time, within their specialty. [Barbara A. Hanawalt, editor, Women and Work in Preindustrial Europe, Indiana University Press, 1986, chapter 6]

Sex and Modesty

Sexual mores vary over cultures. The puritanical, post-Victorian mindset prominent in 20th century USA is unique to a specific era, and is in fact unusual.

Here’s a folk proverb from the territory of Savoy: “No house was ever shamed by a girl who let her skirts be lifted.”

Zhou Daguan, the 13th century Chinese envoy whom we’ve met before, was startled by many things Khmer; for example, the unapologetic sexual feelings expressed by women.

“If a husband doesn’t meet his wife’s wishes he will be abandoned right away […] If the husband happens to have work to do far away, if it is only for a few nights that is all right, but if it is for more than ten nights or so the wife will say, ‘I’m not a ghost—why am I sleeping alone?’”

Bathing customs also come in for scrutiny. Modesty doesn’t mean the same thing across cultures, and nudity is not always linked to sexuality.

“Everyone, male and female, goes naked into the pool. […] For people from the same generation there are no constraints.” And, even better (from his perspective): “women […] get together in groups of three to five and go out of the city to bathe in the river. […] You get to see everything, from head to toe.” [Zhou Daguan, pp 56, 81].

Seen across time, premarital and extramarital sex are not rarities; they’re common and, in some cases, expected. Some cultures have no restriction on premarital sex because marriage is not, in those cultures, about sexual access, nor is a woman’s virginity a universally prized commodity.

There can be policy reasons for extramarital sexual relations as well.

“Plutarch preserves an anecdote that implies that Alexander encouraged Cleopatra [his sister] to take lovers rather than remarry, much as Charlemagne later did with his daughters.” [Carney, p 90]

Sex work, too, must be considered with nuance rather than the Playboy-bunny-style courtesan and willing-or-thieving whore who turn up with odd regularity in science fiction and fantasy novels.

“Among people who believed that simple fornication or adultery by married men with unmarried women was not all that bad, prostitutes might be just another sort of service worker. They could be part of networks of women within towns, associating with other servant women if not with their mistresses. One London case involved a prostitute who gave other women information about the sexual prowess (or rather lack of it) of potential marriage partners, reporting ‘that certain young men which were in contemplation of marriage with them had not what men should have to please them.’ One man sued her for the damages he sustained in losing the opportunity to marry a rich widow.” [Ruth Mazo Karras, Sexuality in Medieval Europe, 2005. p 107]

Don’t despair, however. You can totes have your sexy spy women who use lust to destroy the enemy.

Kautilya’s The Arthashastra (written no later than 150 CE) is an extensive handbook for the art of government, and a pretty ruthless one at that (Machiavelli, eat your heart out). Besides wandering nuns (ascetic women) acting as roving spies, the section “Against Oligarchy” suggests using lust to weaken the bonds between a council of chiefs whose solidarity the king wishes to disrupt:

“Brothel keepers, acrobats, actors/actresses, dancers and conjurors shall make the chiefs of the oligarchy infatuated with young women of great beauty. When they are duly smitten with passion, the agents shall provoke quarrels among them. […]” [Kautilya (translated by L.N. Rangarajan), The Arthashastra, Penguin, 1987, p. 522]

Lesbians exist throughout history (and thus certainly before history began to be recorded), although their presence isn’t as well documented as sexual relationships between men. Writer Heather Rose Jones’s “The Lesbian Historic Motif Project” does so much so well that I am just going to link you to it.

Also, please remember there is no one universal standard of beauty. The current Hollywood obsession with thinness is a result of modern food abundance. In societies with high food insecurity, heavier women may be perceived as healthier and more attractive than their thin counterparts. It’s not that slender women could not be considered beautiful in the past, but if every girl and woman described as beautiful in a book is thin or slender according to modern Hollywood standards (which have changed a great deal even compared to the actresses of the 1920s), or if weight-loss by itself is described as making a character beautiful, then this is merely a modern USA-centric stereotype being projected into scenarios where different beauty standards would more realistically apply. This should be equally obvious in terms of other aspects of perceived beauty, like complexion, hair, features, body shape, and ornamentation.

Any cursory read of world literature reveals an emphasis on male beauty and splendidness as well. In Genesis, Joseph is described as “well built and handsome,” which gives Potiphar’s wife at least one reason to make unwanted advances toward him. In his book The Origins of Courtliness: Civilizing Trends and the Formation of Courtly Ideals 939-1210 (University of Pennsylvania, 1985), C. Stephen Jaeger notes that “An impressive appearance was all but a requirement for a bishop.” He goes on to note the example of Gunther of Bamberg (died 1065) who, it was said, “so far surpassed other mortals in ‘formae elegentia ac tocius corporis integritate’ that in Jerusalem great crowds gathered around him wherever he went in order to marvel at his beauty.” I don’t make this stuff up, people.

Rape

Oh, everyone knows how to write about rape. It’s a popular way to include women in an epic fantasy or historical narrative, whether written in explicit detail or merely implied (as in all those Conan comics of the 70s). Fantasy novels are littered with raped women, possibly more raped women than women serving any other plot function except sex work. (And wouldn’t that be an interesting statistical survey?)

If you must include rape (and there can be reasons to include rape), know that there’s nothing new, bold, or edgy in writing violent scenes from the point of view of the person who is inflicting harm, suffering, and fear; that’s the status quo. Flip the lens. Try writing from the point of view of those who survive, and not only as a revenge fantasy or “I became a warrior because I was raped.” Consider how people endure through terrible trauma and how some are broken by it while others are able to build a new life for themselves. Consider how ripples spread through an entire family or village or society.

Not all cultures offer the same treatment to women captives, either.

“‘Generally,’ as the eighteenth-century French traveller [in North America] J.C.B. put it, ‘savages have scruples about molesting a woman prisoner, and look upon it as a crime, even when she gives her consent.’” [James Wilson, The Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native America, Grove Press, 1998, p. 141]

Gives one a different perspective on the word ‘savage,’ doesn’t it?

Children

It’s not remotely unrealistic (or anti-feminist, as I was once told) to include pregnant women, children and the care of children, and women wanting children in books as matters of interest and importance.

Stories about the stigma of being a barren woman also matter, because for many women having a child was a necessary and/or desperately desired part of life. At the same time, a childless wife might well have other valuable qualities or connections; her status wasn’t necessarily only contingent on her ability to bear a child.

In polygamous societies stories abound of the tighter bond between children of the same mother as opposed to children who had the same father but a different mother. Sunjata was close to his full sister, Kolonkan, who went into exile with him and used her magic (and her skill at cooking) to aid him. Alexander the Great was known to be close to his full sister, Cleopatra, who acted in his interest after he left Macedonia and who, after his death, was considered an important potential marriage partner for the generals vying for control of his empire because her children would be heirs to the Argead dynasty (the ruling dynasty of Macedonia at that time, which died out when all the remaining descendants of Alexander’s father, Philip II, were murdered).

Not all mothers are nurturing and selfless. Some women are willing to sacrifice a child to hold on to power for themselves. After the death of her husband (and brother) Ptolemy VI, Cleopatra II married another brother, Ptolemy VIII, even though on coronation day he murdered her young son by Ptolemy VI. When Ptolemy VIII then also married her daughter by Ptolemy VI, she and her daughter, now co-wives, competed ruthlessly for power in a contest that eventually resulted in the brutal death of yet another son. In contrast Cleopatra VII (the famous Cleopatra) nurtured and protected her children as well as she was able, raising her eldest son Caesarion (by Julius Caeser) to co-rule with her; after her untimely death he was murdered by Octavian’s agents even though she had arranged for him to escape to the east in the hope of putting him out of reach of the Romans.

Not all women in the past got pregnant and had an unending stream of pregnancies broken only by death in childbirth. Various forms of (more or less successful) birth control have been practiced for millennia. The plant silphium, grown in coastal Libya, is said to have been such an effective contraceptive that it was over-harvested until it became extinct.

Not all women pined for children. Some were perfectly happy without them, and/or dedicated themselves to work or religious matters that specifically prohibited them from childbearing.

Some women, for a variety of reasons, never married.

Single Women

The most clichéd and thus commonest ways to portray single women in fantasy are as women in religious orders or as sex workers. Ugly spinsters who can’t get a date also appear, although in actual fact looks are rarely as important in the marriage market as family connections and money. A common reason that a woman might not marry was that she simply could not afford to or, depending on marriage customs, could not attract an acceptable suitor because of a lack of aforesaid family money and connections.

Enslaved women have often lived in a state of enforced singleness, whether or not they are free from sexual demands (and in almost all cases they are not). Americans are most familiar with the horrific history of the trans-Atlantic chattel slave trade, but slavery has existed in many different forms for millennia. In Europe, for example, slavery continued throughout the Middle Ages, waxing and waning depending on the region and era, and many women were transported great distances from their original homes. Of course human trafficking still goes on today in appallingly high numbers.

Many single women in past eras were employed as domestic servants, but not all were. Some had their own work and households. Throughout the Middle Ages in Europe there were always single women who “had their own smoke,” to use a phrase from the late medieval period in Germany that referred to their ability to support themselves in a household of their own. In Paris, single women and/or widows “found practical, economic, and emotional support in their companionships with other unattached women. […] The Parisian tax records [of the 13th century] support this anecdotal evidence of female companionship by offering us glimpses of women who lived and worked together for years.” [Judith M. Bennett and Amy M. Froide, editors, Singlewomen in the European Past: 1250-1800, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999, p 85 & 193]

Some women didn’t marry because they did not want to marry and had the means to refuse, even in cultures where marriage was the overwhelming outcome for most.

“Ai’isha (bint Ahmad al-Qurtubiyya d. 1010) was one of the noble ladies of Cordova and a fine calligrapher […] She attended the courts of the Andalusian kings and wrote poems in their honour. She died unmarried. When one of the poets asked for her hand she scorned him:

1 I am a lioness, and I will never be a man’s woman.

2 If I had to choose a mate, why should I say yes to a dog when I’m deaf to lions?”

[Abdullah al-Udhari (translator and author), Classical Poems by Arab Women, Saqi Books, 1999, p 160]

A Final Word

Women have always lived complex and multivariate lives. Women are everywhere, if only we go looking. Any of the lives or situations referenced above could easily become the launching point for a range of stories, from light adventure to grimmest dark to grand epic.

Our current discussions about the lives and roles of women are not the first round. In the late 14th century the newly widowed Christine de Pisan turned to writing as a means to support her family. She is most famous for two books defending “the ladies.” To quote from Wikipedia, she “argues that stereotypes of women can be sustained only if women are prevented from entering into the conversation. Overall, she hoped to establish truths about women that contradicted the negative stereotypes that she had identified in previous literature.” Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Pisan was writing in 1405 C.E.

Women have been written out of many histories, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t present. In the epilogue to his book The Secret History of the Mongol Queens (Crown, 2010), anthropologist Jack Weatherford writes “Only grudgingly and piecemeal did the story of the daughters of Genghis Khan and of Queen Manduhai the Wise arise from the dust around me, and only hesitantly and somewhat unwillingly did I acknowledge that the individuals whom I had never studied in school or read about in any book could, in fact, be figures of tremendous historic importance” (p 276).

If we don’t hear about them, it’s hard or even impossible to see them. It’s not only male writers who leave out women; female writers do it too. We all do it because we’ve been told women didn’t and don’t matter unless they were allowed to be like men and do like men, or to support men’s stories, or unless men found them sexually attractive or approved of them. We’re told women were passive and repressed and ignorant and therefore empty. But it isn’t true.

Women’s stories don’t trivialize or dull a narrative. They enrich it. They enlarge it.

It’s easy to place women into epic fantasy stories—and more than one woman, women who interact with each other in multifarious ways and whose stories are about them, not in support of men. In my Tor.com essay “Writing Women Characters,” I elaborate on my three main pieces of advice for those who wonder how to better write women characters:

- Have enough women in the story that they can talk to each other.

- Filling in tertiary characters with women, even if they have little dialogue or no major impact on plot, changes the background dynamic in unexpected ways.

- Set women characters into the plot as energetic participants in the plot, whether as primary or secondary or tertiary characters and whether in public or private roles within the setting. Have your female characters exist for themselves, not merely as passive adjuncts whose sole function is to serve as a mirror or a motivator or a victim in relationship to the male.

Where does that leave us?

David Conrad’s essay on female power in the epic tradition quotes from djeli Adama Diabaté’s telling of the Sunjata story, the Mande epic of the founder of the empire of Mali in the 13th century. [Ralph A. Austen, editor, In Search of Sunjata: the Mande Oral Epic as History, Literature, and Performance, 1999, p 198]

It is a foolish woman who degrades womanhood.

Even if she were a man,

If she could not do anything with a weaver’s spindle,

She could do it with an axe.

It was Maghan Sunjata who first put a woman in government in the Manden.

There were eleven women in Sunjata’s government,

[From among the] Nine suba women and nine nyagbaw.

It was these people who first said “unse” in the Manden:

“Whatever men can do, we can do.”

That is the meaning of unse.

Kate Elliott is the author of numerous fantasy & science fiction novels, including Black Wolves, Cold Magic, Jaran, and the YA fantasy Court of Fives. You can find out more about her work at her website. Many thanks to Ellen B. Wright, Liz Bourke, Aliette de Bodard, Cheri Nagashima, and Ann Marie Rasmussen for comments and encouragement on this piece.