Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

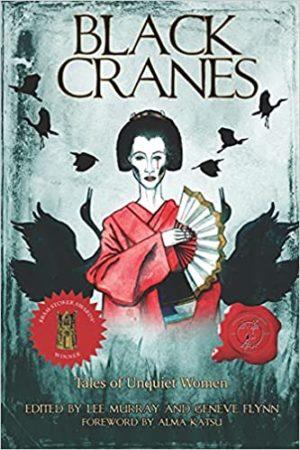

This week, we cover Grace Chan’s “The Mark,” first published in Lee Murray and Geneve Flynn’s Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women, winner of this year’s Shirley Jackson award for best anthology. Spoilers ahead, and content warnings for domestic abuse, rape, unwanted abortion, and genital self-harm.

“My husband of ten years is a stranger.”

For Emma Kavanagh, things haven’t been right for months. She has trouble pinpointing the problem, but the air itself feels “spongy, each molecule bloated with turgid energy.” Lightning storms have plagued the region this summer, producing purple bolts but no rain. It’s as if “some god has reached down, and, with a colossal finger, nudged the Earth, and now everything is sitting two degrees off-kilter.”

One morning, when her husband James returns from his run and strips to shower, she notices a strange mark at the base of his sternum. It looks like a stamp, with “the muted redness of an old scar,” but touched by a stray sunbeam it “gleams silver.” James says it’s nothing, a birthmark he’s had forever, but after the intimacy of ten years of marriage, Emma knows this isn’t true. James leaves for work; she lies in bed, smelling something like bleach, something like burning metal, not quite either. A text from her fellow PA at a gastroenterology practice finally rouses her to the effort of getting up.

That night she—dreams?—that she pulls the sheets back from James’s chest and sees that the mark isn’t flat but raised. She touches it, realizes it’s a zipper pull. When she pulls on it, “the skin of [her] husband’s torso divides soundlessly, like the front of a hoodie, revealing a black, gaping gash.” Before she can examine what lies within, the loud banging of her bathroom pipes wakes her. James isn’t in bed. From the sound of it, he’s pacing around the apartment, “a curious rhythm to his steps.” The footsteps give way to a musical sound “like someone tapping a beat on the rim of a drum with a pair of chopsticks.” It muffles James’s murmur, so she can’t make out his words. Creeping to the bedroom door, she does pick out her own name. Confronted, James claims he’s talking to a new client. Back in bed, Emma realizes he wasn’t holding a phone.

March 8 is the anniversary of the death of Emma’s miscarried daughter. She stands in what was the nursery, now a library, examining the scant memorabilia of Jasmine’s semi-life, and that of Jade, whom Emma aborted three years previously—James convinced her the time was wrong for them to become parents. Jasmine they wanted, but she died at 17 weeks gestation. Emma believes the wanted child died because they aborted the untimely one. She must make amends through penance, which involves her thrusting the corrugated handle of a broken flashlight into her vagina, despite the “monstrous pain.”

On a cold April night she wakes to find James on top of her, eyes glassy. He doesn’t respond when she says his name. As he moves above her, she watches the mark, “a triangle, beautiful in its symmetry. Raised around the edges and silvery-red.”

Emma and James host his business partner Nish, a new client, and their two wives for dinner. Emma notes how James laughs at the client’s jokes and compliments his wife on her knowledge of classical history. All the while his “flat and waxy” hand fidgets on the table, creasing his napkin, flopping like a pale fish. Hers rests beside it, “small and dark and neat.” She presses her pinky to his, finding his skin “cold as dead meat” before he moves away. After dinner, while the others talk, Emma breaks from dishwashing to look into the back yard. James has always been an avid gardener, but this year he’s neglected it.

Everything falls into place as soon as Emma realizes the bizarre truth. That electrified air she’s been feeling is “charged with radio waves transmitting messages to [James’s] system.” His 4 a.m. calls must actually be him checking in with whatever intelligence agency has “commissioned him.” The mark? That’s “the final stitch in his fabrication.”

Buy the Book

Summer Sons

She’s told no one the truth; she’ll pretend everything’s normal until she figures out what to do. She watches James go through the motions of his daily routine, but even his face isn’t right. His eyes are too far apart, his eyebrows tattoo-dark, his thinning hairline restored to fullness. And the moles by his left nostril? Completely gone.

Emma asks James if he remembers Jasmine’s first sonogram and how the Irish sonographer was excited to meet a Mrs. Kavanagh until she saw from Emma’s “black hair, chestnut skin, single-lidded eyes” that she was no fellow Irishwoman. James, however, the sonographer “adored” and kept asking about his Irish relatives. James says he doesn’t remember any of that. How could he forget, Emma asks, about how the sonographer “started implying that you’d bought me from some third-world slum?”

“You always read too much into these little things,” James replies. Emma’s skin prickles at how “hollow” and “alien” his voice sounds.

That night she watches it sleep. It lies flat and still as a corpse, though it breathes. Its fingernails look “like plastic discs, glued on.” The mark gleams, “tempting [her] to touch it and tug it and watch everything unravel.” Emma has brought a metal spoon into the bedroom. She presses its edge into the soft flesh below his left eye. As she suspected: There are wires, and as she digs around the eye socket, cold conducting fluid wets her fingers.

“In the back of [her] mind, [Emma] wonders where the real James has gone.”

What’s Cyclopean: The problem with James intrudes itself as scent: “sort of like bleach, sort of like burning metal.”

The Degenerate Dutch: James’s superficial friends opine that the #MeToo movement’s “breadth is its weakness.”

Weirdbuilding: Emma’s opening description of an off-kilter world, nudged by some god with a “colossal finger,” echoes a cosmic horror image that hasn’t lost its power for being frequently invoked.

Libronomicon: Less commonly invoked in weird fiction is Hemingway. But Emma has in her drawer baby socks, never worn.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The ambiguity between “real” extra-mundane horror and what looks an awful lot like schizophrenia symptoms is somewhat on point, given that difficulty telling what’s real is itself a schizophrenia symptom. [ETA: Anne sees alternate diagnoses, also plausible.]

Anne’s Commentary

In an interview on HorrorAddicts.net, Grace Chan notes that she is “fascinated by both the expanse of the universe and the expanse of our minds.” Because her Aurealis Award-nominated story, “The Mark,” proves her to be a seasoned explorer of the second expanse, I wasn’t surprised to learn that in addition to writing fiction, she’s also a doctor working in psychiatry. Asked by interviewer Angela Yuriko Smith which of her characters best represents her, she replies:

I think I put a kernel of myself into every story…and then I craft a new character around that. Emma Kavanagh, from The Mark, is a character whose perspective and pain is silenced by society. I drew on the experience of women of colour, of being unheard and unseen, because your voice isn’t the right one for the room.

The most pointed example Emma gives of her invisibility and inaudibility is the way her sonographer lost interest in “Mrs. Kavanagh” as soon as she saw Emma was Asian, not Irish like herself. With Mr. James Kavanagh, on the other hand, the sonographer engaged in an animated conversation about his Irish connections. I imagine Emma on the examination table feeling not like the mother-to-be center of attention but like an inconvenient slab of meat needing probing. To make matters worse, James shrugs off her remembered sense of slighting with “You always read too much into these little things.” To him, the microaggression was no aggression at all, just the sonographer “trying to be nice.”

James’s cumulative dismissals must amount, for Emma, to a macroaggression. Or to no aggression at all, because you aggress against other people, not against one more accessory to your busy professional life. A major accessory, responsible for laundry and arranging business dinners and having children at the right time and not before, but still. Accessories need to be reliable, and Emma has been that. Her gastroenterologist employer, coincidentally (but tellingly) also named James, refers to her as the “queen of his office” because he does rely on Emma, but he does it “tongue-in-cheek,” condescendingly.

Trying to characterize the ambient wrongness of her last few months, Emma describes the air as “bloated with turgid energy.” Weird storms have plagued the summer, bringing clouds that bear no rain, only “purple branches” of lightning. Eventually she pins the wrongness on James. He’s become or been replaced by a mechanical doppelganger of the man she married—the electrical disturbances are “radio waves” his controllers (minions of some shadowy intelligence agency) use to communicate with him! Or—

Or does the “turgid energy” represent Emma’s own accumulated resentment? Is she herself not a rainless (barren) cloud pounding the arid earth with thunderbolts of repressed rage? By projecting her inner emotional world upon the natural world, has Emma committed that good old pathetic fallacy on her way to becoming an unreliable narrator?

That’s the crux of the story. Is Emma right, or is she experiencing a mental breakdown? Perhaps she’s diagnosable as a victim of Capgras, a delusional misidentification syndrome in which the patient believes someone close to them has been replaced by an identical impostor. It’s a tough question to answer. Evidence mounts that James is an impostor, either a replacement for the original or the original morphed into a truer representation of his automatonic self, of his essential otherness from Emma, which is also Emma’s otherness from him and his world. Problem is, it’s Emma citing the evidence. Does James bear the Mark of the Zipper-Pull, or is it a birthmark she now conjures into something new and sinister? Is his skin as cold as dead meat, are his features distorted, does he have wires for nerves and conducting fluid for blood, or are these merely Emma’s addled perceptions? For the ultimate horror, does he lie passive while she spoon-gouges out his eye because he’s an it, an insensate machine, or because Emma’s slipped him one hell of a mickey?

Does it matter to the impact of the story whether what Emma experiences is real or whether she suffers from delusions? Whether James is a Stepford husband, a pod-person, an android agent of shadowy ill-intenders? Or whether he’s “just” a slyly oppressive jerk of a husband? The background tragedies of aborted Jade and miscarried Jasmine, coupled with the ongoing trauma of racism, may give Emma fuel enough for a mental breakdown. Her terrible ritual of self-torturing atonement via flashlight dildo may be an ongoing expression of her disorder. Or—

She may be perfectly sane (apart from the flashlight thing): Stepford husbands, pod-people, and android imposters exist, and one of them is sleeping in her bed.

My preference for “real monster” stories over “all-in-their-head” stories can be overcome by the power of a subtle and/or novel approach. Chan leaves it to the reader to decide which “The Mark” is; pushed, I’d go with delusion over android, but I’d rather relax in the ambiguity. Ultimately, if a character (or actual person) has an unshakeable belief in their delusion, then the horror of that delusion is more than real enough for them—and for the happily susceptible reader.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I picked “The Mark” from Shirley-Jackson-winning Black Cranes based on reading the first couple of pages. Emma’s description of an unreal-feeling world, of trying to reassure herself that the sky wasn’t simply a surface glued over a false skeleton, reminded me of The Hollow Places. It’s a classic moment of cosmic horror: everything that makes for a comfortable, comprehensible reality is mere illusion, and the only thing worse than knowing is having the illusion ripped away and being forced to confront—or just acknowledge—whatever’s underneath.

But Emma’s in a much worse situation than Kara. No trustworthy friend by her side, let alone another Asian-American woman who might share similar experiences and check her fears. No haven of weirdness to return to, let alone a welcoming home. “There’s something horribly wrong with my husband.” Honey, there’s been something horribly wrong with your husband the whole time. It’s just that now he’s also an android. An almost-convincing surface illusion, with something terrible and hungry—and demanding that you cook dinner—underneath.

He is an android, yes? I have a rule, only occasionally broken, which is that whenever a story tries to raise doubts about the in-universe reality status of fantastic elements, I err on the side of the fantastic. This is for my own sake: I vastly prefer fantasy and horror over mimetic fiction about people suffering from mental illness. I’m good with fantasy and horror about people suffering from mental illness, in which category this certainly seems to fall. After reading the whole thing, it reminds me less of The Hollow Places and more of “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

Emma’s had very little choice in her life—perhaps it’s even the surface illusion of a life, stretched over something empty. Her job consists of responding to one James’s demands; her home life consists of responding to another’s. She mentions her parents’ approval of her husband’s nose, never any attraction of her own, suggesting that if not strictly an arranged marriage (unlikely given their differing backgrounds), it was an encouraged marriage. Abortion is the center of so many conversations about women’s right to control our own bodies, but it’s clear that James was the driving force behind hers, making her among the few who regret getting one.* She seems way too used to holding still and dissociating while James rapes her. Her “penance” (oh god that was a hard scene to read, in a story full of incredibly hard scenes) seems like a desperate attempt to reclaim control.

Against all that, cutting through the surface to find wires and circuits underneath seems like it might be a relief.

My interpretation, not terribly well-supported by the text but fitting better than either “just horror” or “all in her mind,” is that it’s not government agents, but Emma’s own misery, that’s marked James and turned him into whatever he’s become. The only way she could gain control of anything was to gain control of reality itself, and make her tormenter into something that she feels like she’s allowed to hate. If he’s not her original husband, then she’s allowed to question, allowed even to destroy. It’s a permission that she desperately needs, and—real or otherwise—she’s given it to herself.

*Note: I’ve addressed abortion here given the central role it plays in the story, but want to note that we are not interested in debating abortion rights or morality in the comments section. Comments to that effect will be considered off-topic.

Next week, will the people who want the evil book find it? Will the people who don’t want it manage to avoid it? Join us for Chapter 3 of John Connolly’s Fractured Atlas.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Many years ago I read a comic book where the protagonist, married to a career woman who has no time for her husband, one night sees blue light spilling from a slit in her skin as she sleeps. The slit widens and a beautiful, naked, alien looking hairless blue woman emerges, has sex with the protagonist, and goes back into the skin come morning. The career wife wakes with no knowledge of what happened. This goes on every night for a while until the husband hides the career wife’s skin. The blue wife, perforce, is now his all day as well as all night, but can’t go to work so works from home over the phone or something (it was many years ago). I believe the denouement was that one day the husband found blue light spilling out through a slit in his own skin.

I obviously immediately thought of that comic book while reading this reread.

No comments this week, shame! I liked what Ruthanna said about erring on the side of the fantastic. It’s the only way for the story to keep going, right, because otherwise Emma will just go to prison. Plus, I’m all for interpreting things in a way that DOESN’T just give us one more example of “mentally ill lady is homicidal” even if she would be justified.

I’m excited to pick up this anthology, it sounds amazing.