Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

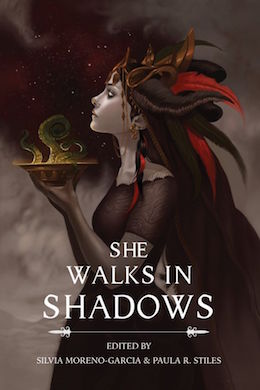

Today we’re looking at Premee Mohamed’s “The Adventurer’s Wife,” first published in the 2015 anthology, She Walks in Shadows, edited by Silvia Moreno-Garcia and Paula R. Stiles. Spoilers ahead.

“The men had built a door—as if all the world, Mr. Greene, was a hut, yet it had been built with no way in, and the men had chopped a door into the hut.”

Summary

Henley Dorsett Penhallick, renowned for fifty years as the pre-eminent explorer and adventurer of his age, has died, leaving behind a surprise widow. What’s the surprise? No one knew the self-styled bachelor had a wife! Soon after the funeral—too soon to be seemly, Greene thinks—his editor sends him to interview the lady before their competitor papers get first crack at the “crystal-like droplet that rolls down her wan face.”

Greene finds her alone in the ivy-draped house: a petite woman with hands sheathed in black silk, face obscured by a thick veil. Guilty at disturbing her, he stammers his way through an introduction. After a long pause, she lets him enter. The smell of incense and flowers is overwhelming—funeral arrangements fill a parlor and spill into the hall. The stairs draw his attention, for each step hosts an exotic wood carving. Dominating the landing is a world map with hundreds of brass pins, flagging all the places Penhallick visited.

They’ll take tea in the kitchen, Mrs. Penhallick says, if Mr. Greene will forgive the informality. She’s doing for herself at the moment, having given the house servants a week off. Greene asks: Has she no family she could stay with?

No one nearby.

Greene surreptitiously records the practiced assurance with which she makes the tea, and the care she takes to drink hers without disturbing her veil and revealing her face. He admits that many journalists who corresponded with her husband never met him. The widow’s not surprised. Penhallick was a very private man. Why, few family and friends knew of their marriage. There was no announcement, though it was recorded in the local registry.

Before Greene can respond, she removes hat and veil. He freezes, then gulps burning tea to hide his shock. She’s no “purse-mouthed old bat from a leading family but a girl with the huge, steady eyes of a deer and burnished young skin as dark and flawless as the carved mahogany jaguar on the third stairstep.” A bright scarf wraps her head. He stammers, swallows. She smiles at his discomfiture. If he wants her story, come see the house.

She leads him to the map, and points out a pin in a borderless expanse of Africa. Her name is Sima, and that was her home, a beautiful place fifty thousand years old when the nation of the white man was in its infancy. Ten years before, Penhallick came there and explored the holy ruins near her village. At night he’d tell stories by their fire. Some of her people, including Sima, he taught English. What a collector he was, hands always darting out for a rock, fossil, flower, or feather. The villagers told him he mustn’t take anything from the holy ruins, though he could draw and copy inscriptions.

When Sima was grown, he returned. Against her father’s wishes, she followed Penhallick and the village men to the ruins, a circle of eight stone towers with a gate of basalt blocks. Elder Olumbi told Penhallick that their ancestors built it for old gods who couldn’t speak, but could nevertheless command. Men who’d only worked wood and clay now carved stone. They didn’t know just what they were doing, only that they had to do it. When they were done, the old gods entered our world with their terrible servants, the shoggoths, which men cannot see. They wrought wanton destruction until foreign magicians drove the old gods back to their unholy realm.

Sima later saw the adventurer pry loose a carving of a thing with snakes for its face. Though she knew he must take nothing from the ruins, she held her tongue. What calamity could possibly follow so small a theft? Yet soon Penhallick grew pale and restless, walking at night and talking to himself.

When three years later he returned again, he looked like “a drought-stricken animal about to die.” He seemed surprised when Sima told him there’d been no disasters during his absence. That night she accompanied him to the ruins, where he replaced the stolen carving and begged for the curse he’d brought on himself to be lifted. The ground moved and roared like a lion. The curse clung. He asked Sima’s family to let her come with him as his wife; they consented. The two married and returned to America.

Penhallick now traveled to Miskatonic University with his African notebooks. He brought back notes from one of their old books. The rituals he’d recite from it at night seemed to shake the house! But he recovered. He began to talk of new adventures they’d pursue together. But his doom was still with them. She learned a word unknown in her own language, which was penance.

When she falls silent, Greene asks how Penhallick died, if not from his illness.

Eyes suddenly hard, Sima says that her husband struck a devil’s deal with the old gods, and the cost was his life. They sent a shoggoth to collect payment.

The poor girl’s mad, Greene thinks, mind snapped by her isolation in a strange land. Preparing to leave, he remarks that it’s a pity Penhallick died childless.

Why, Sima never anything of the sort. Part of the deal for her freedom was Penhallick’s life, but she was well-compensated with a child.

Greene gets out a confused “But…” before something comes racing downstairs, unseen except for the brass pins it tears from Penhallick’s map in its wake.

What’s Cyclopean: Cheltenwick seems like he’d appreciate—even demand—purple prose, but Greene doesn’t provide it.

The Degenerate Dutch: It’s unclear whether Henley keeps his marriage secret because he’s just that private, or because his friends and family would so thoroughly disapprove of his African bride. Greene can’t imagine where they could have gotten legally married.

Mythos Making: Ignore the curse on the mummy’s tomb if you want, but mess with shoggoth-infested ruins at your peril.

Libronomicon: Henley gets a book from Miskatonic to help with his shoggoth problem. It doesn’t help.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Greene listens to Sima’s story, and decides she’s gone mad from grief. She hasn’t gone mad.

Anne’s Commentary

[AMP: My psyche’s taking a break this week at a lush resort in primordial Australia, while a Yith historian wears my body to consult the anthropodermic books in the John Hay Library. No worries—my good friend Carl Kolchak has volunteered to write this week’s commentary, eager to follow in the footsteps of fellow journalist Greene in interviewing the fascinating Mrs. Penhallick. So long as those footsteps stop short of invisible maws, of course.]

Greene disappeared long before I was born, back when adventurers really did venture into regions unknown to men of pasty complexions, who were the only men whose knowledge counted. It’s not surprising that such superior explorers routinely considered indigenous experience questionable and indigenous warnings superstition-tainted. I’m here, alive and mostly intact, to tell you: Always listen to the locals. And if they start running, run faster, because it’s always good to have someone between you and whatever you’re all running from.

Get pictures first, though.

Greene wasn’t the only journalist who disappeared while on assignment to Mrs. Penhallick. The first couple years after her husband died, three others vanished from editorial ken. Then Mrs. Penhallick herself went missing. A grocer’s delivery boy said she must’ve gone home to Africa, because she was a black African under her veils, and she kept African snakes upstairs, he’d smelled them. People didn’t believe the boy about Mrs. Penhallick, because why would Henley Dorsett Penhallick wed a black woman? They believed him about the snakes, though, because searchers opened a second floor bedroom that exhaled a reek so foul several passed out. Good thing Mrs. Penhallick had taken the snakes with her, or the searchers would’ve been easy prey sprawled on the hall carpet.

Mrs. Penhallick—Sima—never returned to her husband’s house. She sold it through a realtor in Boston, and that was the last anyone in his hometown heard of her. Now, wherever she went afterwards, you’d figure she’d be dead by now, right? Wrong. Never assume someone who’s messed around with old gods must die of something as merely natural as superannuation.

No, Sima never died. A century later, she’s Professor Penhallick, lately installed as Chair of Xenocryptobiology (special interest in macroinvertebrates) at Miskatonic University; looking little older than Greene’s girl-widow, bold scarf now knotted through a crown of braids. She sighed when I mentioned him during our recent meeting in her MU office. “It’s difficult being a new mother with no one to instruct you,” she said. “Not that my mother or aunts could have done so. My child itself had to show me how to feed it .”

“By eating the servants?” I conjectured.

“Just so, I’m afraid.”

“Then Mr. Greene.”

She smiled. She understood how freely she could speak to me, since nobody believes a damn word I write. “He was a godsend.”

“What did it eat between reporters?”

“Sometimes I had to be stern. Children can’t always have what they like best. Stray dogs or cats, mostly.”

“Or stray people?”

“Sometimes.”

Her voice sank in those two syllables. “You regretted it?”

Though Sima’s voice remained low, her eyes met mine steadily. “I regretted the stray people. What had they done to deserve my child’s hunger?”

“You didn’t regret the reporters, though?”

“Now, Mr. Kolchak. Where I was born, we have leeches. They’d latch on my ankles, I’d pull them off, but I wouldn’t kill them, I’d let them go. They couldn’t help sucking blood. It was their nature.”

I might have imagined the shift of air around my own ankles, but I moved the conversation on fast: “And your husband? Any regrets there?”

Her face relaxed back into a smile more chilling than any snarl could have been. “Not after the instant I realized he meant to give the old gods my life in exchange for his. It was as if I had seen him bathed gold in sunbeams, but the sun came from my eyes. His own true light welled from inside him, gray, sick moonbeams. He saw less than he thought he did, so he put aside my people’s wisdom. He stole from the old gods’, and they were right to curse him. It could not be right for me to bear the curse for him.”

“But didn’t others bear it for you?”

“What they bore was for my child, not for me. A very different thing, you’ll understand.”

“I don’t have any—kids, Professor.”

“Use your imagination, then.”

Given I already imagined nuzzling at my right knee, I didn’t want to give the faculty more rein. “Point taken. Well, thanks for your time.”

I was at the door when Professor Penhallick said, “Mr. Kolchak, about my child? I keep it frozen now. The ethereal shoggoths are more sensitive to cold than the cruder ones the Elder Race fashioned in Antarctica. Cold lulls them to sleep, lets them dream unfamished. They like to dream. I like to save resources.”

As a potential resource, I had to nod approval of her frugality. Then I beat it the hell out of there.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I first read this story a while back in She Walks in Shadows, but was reminded of Premee Mohamed’s work not only by CliftonR’s recommendation in our comments, but by “More Tomorrow,” her delightfully disturbing tale of time travel and grad student exploitation. “The Adventurer’s Wife” is similarly a story that might sit on the edge of other stories—how often, in this Reread, have we had direct the saga of some overconfident adventurer retrieving ill-advised artifacts?

More, in Lovecraft we’ve found stories of adventurers retrieving ill-advised wives, their nature revealed as ostensibly obscene punchlines. Martense breeds with Martense, degenerating into animalism. Arthur Jermyn’s mother turns out to be a (talking, sapient) white ape. Marceline’s true nature is revealed dramatically as not merely gorgon, but “negress.”

Sima tells her own story—willing, now that her husband has died, to be a revelation but not a secret. She comes from what might be a literary “lost world,” a place on the African map where white men haven’t yet managed to mark borders. No Afrofuturist Wakanda, though, Sima’s land is a forgotten guard post. Perhaps it was one of the first places rebuilt after the last ravening of the old gods. They build with clay, never moving stone; each object has its place, carefully preserved. And for good reason, it turns out. Still, it sounds like a frustrating place for an adventurous girl to grow up, and I can’t really blame Sima for finding Henley exciting despite his poor judgment. Bringing him through an antique store must be worse than dragging along a toddler: Don’t touch that. Don’t touch that either! It’s a miracle his bedroom isn’t already full of one-legged mummies and dog-eared copies of The King in Yellow.

But then, maybe she has other reasons to leave. Henley trades his life for Sima’s “freedom.” Freedom from what? From the “cries in the night” and “blood on the sand” that Henley expects as the result of his theft? From some amorphous vengeance that would otherwise have been visited on his family? From the constraints of life with her people? And then, our ultimate revelation isn’t in fact Sima’s heritage but her child’s. Olumbi’s story suggests that her people are sympathetic neither to the old gods nor to their “servants” the shoggothim. Yet Sima considers herself “well-compensated” by a shoggoth baby. Half-shoggoth? After all, she doesn’t merely deny that she’s childless, but that Henley died “without issue.” The mind reels.

Actually, the mind really wants the story of Sima dealing simultaneously with the absurdities of her late husband’s culture while trying to raise an invisible alien baby. Note that Sima glosses Henley’s unnamed country as “the nation of the white man,” singular. Exoticization goes both ways.

It’s an interesting choice, because it moves the shoggothim from legendary, all-destroying monsters to people. Not only must Sima see them that way to love and raise one, but they must see her as one to let her do so. Unless this is more of a changeling exchange—after all, paying with one’s life doesn’t always involve dying. In either case, while the ending could be interpreted as a shocker along the lines of “Arthur Jermyn,” there does seem to be more going on here. At least, Sima herself doesn’t seem entirely distressed at the way things have worked out.

Greene, on the other hand, is going to have a hell of a time writing that article, even assuming he’s not about to get gobbled by a hyperactive blob of juvenile protoplasm. Crystal-like droplets indeed.

[ETA: I just realized: it cannot be a coincidence that our narrator shares Sonia Greene’s surname. No good place to stick this in above, but it’s a nice touch.]

Next week, we move from adventure to tourism in Robert Silverberg’s “Diana of the Hundred Breasts.” You can find it in The Madness of Cthulhu as well as several other anthologies.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.