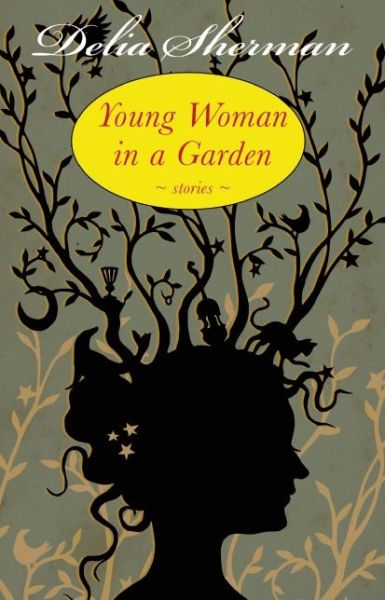

In her vivid and sly, gentle and wise, collection of short stories, Delia Sherman takes seemingly insignificant moments in the lives of artists or sailors—the light out a window, the two strokes it takes to turn a small boat—and finds the ghosts haunting them, the magic surrounding them. Here are the lives that make up larger histories, here are tricksters and gardeners, faeries and musicians, all glittering and sparkling, finding beauty and hope and always unexpected, a touch of wild magic.

A long anticipated first collection of fabulous stories with ghosts, fairies, artists, and even a merman—Delia Sherman’s Young Woman in a Garden is available November 11th from Small Beer Press. Read an excerpt from a story titled “Walpurgis Afternoon” below!

Walpurgis Afternoon

The big thing about the new people moving into the old Pratt place at Number 400 was that they got away with it at all. Our neighborhood is big on historical integrity. The newest house on the block was built in 1910, and you can’t even change the paint scheme your house without recourse to preservation committee studies and zoning board hearings. Over the years, the Pratt place had generated a tedious number of such hearings—I’d even been to some of the more recent ones. Old Mrs. Pratt had let it go pretty much to seed, and when she passed away, there was trouble about clearing the title so it could be sold, and then it burned down.

Naturally a bunch of developers went after the land—a three-acre property in a professional neighborhood twenty minutes from downtown is something like a Holy Grail to developers. But their lawyers couldn’t get the title cleared either, and the end of it was that the old Pratt place never did get built on. By the time Geoff and I moved next door, it was an empty lot where the neighborhood kids played Bad Guys and Good Guys after school and the neighborhood cats preyed on an endless supply of mice and voles. I’m not talking eyesore, here; just a big shady plot of land overgrown with bamboo, rhododendrons, wildly rambling roses, and some nice old trees, most notably an immensely ancient copper beech big enough to dwarf any normal-sized house.

It certainly dwarfs ours.

Last spring, all that changed overnight. Literally. When Geoff and I turned in, we lived next door to an empty lot. When we got up, we didn’t. I have to tell you, it came as quite a shock first thing on a Monday morning, and I wasn’t even the one who discovered it. Geoff was.

Geoff’s the designated keeper of the window because he insists on sleeping with it open and I hate getting up into a draft. Actually, I hate getting up, period. It’s a blessing, really, that Geoff can’t boil water without burning it, or I’d never be up before ten. As it is, I eke out every second of warm unconsciousness I can while Geoff shuffles across the floor and thunks down the sash and takes his shower. On that particular morning, his shuffle ended not with a thunk, but with a gasp.

“Holy shit,” he said.

I sat up in bed and groped for my robe. When we were in grad school, Geoff had quite a mouth on him, but fatherhood and two decades of college teaching have toned him down a lot. These days, he usually keeps his swearing for Supreme Court decisions and departmental politics.

“Get up, Evie. You gotta see this.”

So I got up and went to the window, and there it was, big as life and twice as natural, a real Victorian Homes centerfold, set back from the street and just the right size to balance the copper beech. Red tile roof, golden brown clapboards, miles of scarlet-and-gold gingerbread draped over dozens of eaves, balconies, and dormers. A witch’s hat tower, a wrap around porch, and a massive carriage house. With a cupola on it. Nothing succeeds like excess, I always say.

I like to think of myself as a fairly sensible woman. I don’t imagine things, I face facts, I hadn’t gotten hysterical when my fourteen-year-old daughter asked me about birth control. Surely there was some perfectly rational explanation for this phenomenon. All I had to do was think of it.

“It’s an hallucination,” I said. “Victorian houses don’t go up over night. People do have hallucinations. We’re having an hallucination. QED.”

“It’s not a hallucination,” Geoff said.

Geoff teaches intellectual history at the university and tends to disagree, on principle, with everything everyone says. Someone says the sky is blue, he says it isn’t. And then he explains why. “This has none of the earmarks of a hallucination,” he went on. “We aren’t in a heightened emotional state, not expecting a miracle, not drugged, not part of a mob, not starving, not sense-deprived. Besides, there’s a clothesline in the yard with laundry hanging on it. Nobody hallucinates long underwear.”

I looked where he was pointing, and sure enough, a pair of scarlet longjohns was kicking and waving from an umbrella drying rack, along with a couple pairs of women’s panties, two oxford-cloth shirts hung up by their collars, and a gold-and-black print caftan. There was also what was arguably the most beautifully designed perennial bed I’d ever seen basking in the early morning sun. As I was squinting at the delphiniums, a side door opened and a woman came out with a wicker clothes basket propped on her hip. She was wearing shorts and a t-shirt, had fairish hair pulled back in a bushy tail, and struck me as being a little long in the tooth to be going barefoot and braless.

“Nice legs,” said Geoff.

I snapped down the window. “Pull the shades before you get in the shower,” I said. “It looks to me like our new neighbors get a nice, clear shot of our bathroom from their third floor.”

In our neighborhood, we pride ourselves on minding our own business and not each others’—live and let live, as long as you keep your dog, your kids, and your lawn under control. If you don’t, someone calls you or drops you a note, and if that doesn’t make you straighten up and fly right, well, you’re likely to get a call from the Town Council about that extension you neglected to get a variance for. Needless to say, the house at Number 400 fell way outside all our usual coping mechanisms. If some contractor had shown up at dawn with bulldozers and two-by-fours, I could have called the police or our Councilwoman or someone and got an injunction. How do you get an injunction against a physical impossibility?

The first phone call came at about eight-thirty: Susan Morrison, whose back yard abuts the Pratt place.

“Reality check time,” said Susan. “Do we have new neighbors or do we not?”

“Looks like it to me,” I said.

Silence. Then she sighed. “Yeah. So. Can Kimmy sit for Jason Friday night?”

Typical. If you can’t deal with it, pretend it doesn’t exist, like when one couple down the street got the bright idea of turning their front lawn into a wildflower meadow. The trouble is, a Victorian mansion is a lot harder to ignore than even the wildest meadow. The phone rang all morning with hysterical calls from women who hadn’t spoken to us since Geoff’s brief tenure as president of the neighborhood association.

After several fruitless sessions of what’s-the-world-coming-to, I turned on the machine and went out to the garden to put in the beans. Planting them in May was pushing it, but I needed the therapy. For me, gardening’s the most soothing activity on earth. When you plant a bean, you get a bean, not an azalea or a cabbage. When you see that bean covered with icky little orange things, you know they’re Mexican bean beetle larvae and go for the pyrethrum. Or you do if you’re paying attention. It always astonishes me how oblivious even the garden club ladies can be to a plant’s needs and preferences. Sure, there are nasty surprises, like the winter that the mice ate all the Apricot Beauty tulip bulbs. But mostly you know where you are with a garden. If you put in the work, you’ll get satisfaction out, which is more than can be said of marriages or careers.

This time, though, digging and raking and planting failed to work their usual magic. Every time I glanced up, there was Number 400, serene and comfortable, the shrubs established and the paint chipping just a little around the windows, exactly as if it had been there forever instead of less than twelve hours.

I’m not big on the inexplicable. Fantasy makes me nervous. In fact, fiction makes me nervous. I like facts and plenty of them. That’s why I wanted to be a botanist. I wanted to know everything there was to know about how plants worked, why azaleas like acid soil and peonies like wood ash and how you might be able to get them to grow next to each other. I even went to graduate school and took organic chemistry. Then I met Geoff, fell in love, and traded in my PhD for an MRS, with a minor in Mommy. None of these events (except possibly falling in love with Geoff) fundamentally shook my allegiance to provable, palpable facts. The house next door was palpable, all right, but it shouldn’t have been. By the time Kim got home from school that afternoon, I had a headache from trying to figure out how it got to be there.

Kim is my daughter. She reads fantasy, likes animals a lot more than she likes people, and is a big fan of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Because of Kim, we have two dogs (Spike and Willow), a cockatiel (Frodo), and a lop-eared Belgian rabbit (Big Bad), plus the overflow of semi-wild cats (Balin, Dwalin, Bifur, and Bombur) from the Pratt place, all of which she feeds and looks after with truly astonishing dedication.

Three-thirty on the nose, the screen door slammed and Kim careened into the kitchen with Spike and Willow bouncing ecstatically around her feet.

“Whaddya think of the new house, Mom? Who do you think lives there? Do they have pets?”

I laid out her after-school sliced apple and cheese and answered the question I could answer. “There’s at least one woman—she was hanging out laundry this morning. No sign of pets, but it’s early days yet.”

“Isn’t it just the coolest thing in the universe, Mom? Real magic, right next door. Just like Buffy.”

“Without the vampires, I hope. Kim, you know magic doesn’t really exist. There’s probably a perfectly simple explanation for all of this.”

“But, Mom!”

“But nothing. You need to call Mrs. Morrison. She wants to know if you can sit for Jason on Friday night. And Big Bad’s looking shaggy. He needs to be brushed.”

That was Monday.

Tuesday morning, our street looked like the expressway at rush hour. It’s a miracle there wasn’t an accident. Everybody in town must have driven by, slowing down as they passed Number 400 and craning out the car window. Things quieted down in the middle of the day when everyone was at work, but come 4:30 or so, the joggers started and the walkers and more cars. About 6:00, the police pulled up in front of Number 400, at which point everyone stopped pretending to be nonchalant and held their breath. Two cops disappeared inside, came out again a few minutes later, and left without talking to anybody. They were holding cookies and looking bewildered.

On Wednesday, the traffic let up. Kim found a kitten (Hermione) in the wildflower garden and Geoff came home full of the latest in a series of personality conflicts with his department head, which gave everyone something other than Number 400 to talk about over dinner.

Thursday, Lucille Flint baked one of her coffee cakes and went over to do the Welcome Wagon thing.

Lucille’s our local Good Neighbor. Someone moves in, has a baby, marries, dies, and there’s Lucille, Johnny-on-the-spot with a coffee cake in her hands and the proper Hallmark sentiment on her lips. Lucille has the time for this kind of thing because she doesn’t have a regular job. All right, neither do I, but I write a gardener’s advice column for the local paper, so I’m not exactly idle. There’s the garden, too. Besides, I’m not the kind of person who likes sitting around other people’s kitchens drinking watery instant and listening to the stories of their lives. Lucille is.

Anyway. Thursday morning, I researched the diseases of roses for my column. I’m lucky with roses. Mine never come down with black spot, and the Japanese beetles prefer Susan Morrison’s yard to mine. Weeds, however, are not so obliging. When I’d finished Googling “powdery mildew,” I went out to tackle the rosebed.

Usually, I don’t mind weeding. My mind wanders, my hands get dirty. I can almost feel my plants settling deeper into the soil as I root out the competition. But my rosebed is on the property line between us and the Pratt place. What if the house disappeared again, or someone came out and wanted to chat? I’m not big into chatting. On the other hand, there was shepherd’s purse in the rose bed, and shepherd’s purse can be a real wild Indian once you let it get established, so I gritted my teeth, grabbed my Cape Cod weeder, and got down to it.

Just as I was starting to relax, I heard footsteps passing on the walk and pushed the rose canes aside just in time to see Lucille Flint climbing the stone steps to Number 400. I watched her ring the doorbell, but I didn’t see who answered because I ducked down behind a bushy Gloire de Dijon. If Lucille doesn’t care who knows she’s a busybody, that’s her business.

After twenty-five minutes, I’d weeded and cultivated those roses to a fare-thee-well and was backing out when I heard the screen door, followed by Lucille telling someone how lovely their home was, and thanks again for the scrumptious pie.

I caught her up under the copper beech.

“Evie dear, you’re all out of breath,” she said. “My, that’s a nasty tear in your shirt.”

“Come in, Lucille,” I said. “Have a cup of coffee.”

She followed me inside without comment and accepted a cup of microwaved coffee and a slice of date-and-nut cake.

She took a bite, coughed a little, and grabbed for the coffee.

“It is pretty awful, isn’t it?” I said apologetically. “I baked it last week for some PTA thing at Kim’s school and forgot to take it.”

“Never mind. I’m full of cherry pie from next door. “She leaned over the stale cake and lowered her voice. “The cherries were fresh, Evie.”

My mouth dropped open. “Fresh cherries? In May? You’re kidding.”

Lucille nodded, satisfied at my reaction. “Nope. There was a bowl of them on the table, leaves and all. What’s more, there was corn on the draining board. Fresh corn. In the husk. With the silk still on it.”

“No!”

“Yes.” Lucille sat back and took another sip of coffee. “Mind you, there could be a perfectly ordinary explanation. Ophelia’s a horticulturist, after all. Maybe she’s got greenhouses out back. Goodness knows there’s room enough for several.”

I shook my head. “I’ve never heard of corn growing in a greenhouse.”

“And I’ve never heard of a house appearing in an empty lot overnight,” Lucille said tartly. “About that, there’s nothing I can tell you. They’re not exactly forthcoming, if you know what I mean.”

I was impressed. I knew how hard it was to avoid answering Lucille’s questions, even about the most personal things. She just kind of picked at you, in the nicest possible way, until you unraveled. It’s one of the reasons I didn’t hang out with her much.

“So, who are they?”

“Rachel Abrams and Ophelia Canderel. I think they’re lesbians. They feel like family together, and you can take it from me, they’re not sisters.”

Fine. We’re a liberal suburb, we can cope with lesbians. “Children?”

Lucille shrugged. “I don’t know. There were drawings on the fridge, but no toys.”

“Inconclusive evidence,” I agreed. “What did you talk about?”

She made a face. “Pie crust. The Perkins’s wildflower meadow. They like it. Burney.” Burney was Lucille’s husband, an unpleasant old fart who disapproved of everything in the world except his equally unpleasant terrier, Homer. “Electricians. They want a fixture put up in the front hall. Then Rachel tried to tell me about her work in artificial intelligence, but I couldn’t understand a word she said.”

From where I was sitting, I had an excellent view of Number 400’s wisteria-covered carriage house, its double doors ajar on an awe-inspiring array of garden tackle. “Artificial intelligence must pay well,” I said.

Lucille shrugged. “There has to be family money somewhere. You ought to see the front hall, not to mention the kitchen. It looks like something out of a magazine.”

“What are they doing here?”

“That’s the forty-thousand-dollar question, isn’t it?”

We drained the cold dregs of our coffee, contemplating the mystery of why a horticulturist and an artificial intelligence wonk would choose our quiet, tree-lined suburb to park their house in. It seemed a more solvable mystery than how they’d transported it there in the first place.

Lucille took off to make Burney his noontime franks and beans and I tried to get my column roughed out. But I couldn’t settle to my computer, not with that Victorian enigma sitting on the other side of my rose bed. Every once in a while, I’d see a shadow passing behind a window or hear a door bang. I gave up trying to make the disposal of diseased foliage interesting and went out to poke around in the garden. I was elbow-deep in the viburnum, pruning out deadwood, when I heard someone calling.

It was a woman, standing on the other side of my roses. She was big, solidly curved, and dressed in bright flowered overalls. Her hair was braided with shiny gold ribbon into dozens of tiny plaits tied off with little metal beads. Her skin was a deep matte brown, like antique mahogany. Despite the overalls, she was astonishingly beautiful.

I dropped the pruning shears. “Damn,” I said. “Sorry,” I said. “You surprised me.” I felt my cheeks heat. The woman smiled at me serenely and beckoned.

I don’t like new people and I don’t like being put on the spot, but I’ve got my pride. I picked up my pruning shears, untangled myself from the viburnum, and marched across the lawn to meet my new neighbor.

She said her name was Ophelia Canderel, and she’d been admiring my garden. Would I like to see hers?

I certainly would.

If I’d met Ophelia at a party, I’d have been totally tongue-tied. She was beautiful, she was big, and frankly, there just aren’t enough people of color in our neighborhood for me to have gotten over my liberal nervousness around them. This particular woman of color, however, spoke fluent Universal Gardener and her garden was a gardener’s garden, full of horticultural experiments and puzzles and stuff to talk about. Within about three minutes, she was asking my advice about the gnarly brown larvae infesting her bee balm, and I was filling her in on the peculiarities of our local microclimate. By the time we’d inspected every flower and shrub in the front yard, I was more comfortable with her than I was with any of the local garden club ladies. We were alike, Ophelia and I.

We were discussing the care and feeding of peonies in an acid soil when Ophelia said, “Come see my shrubbery.”

Usually when I hear the word “shrubbery,” I think of a semi-formal arrangement of rhodies and azaleas, lilacs and viburnum, with a potentilla perhaps, or a butterfly bush for late summer color. The bed should be deep enough to give everything room to spread and there should be a statue in it, or maybe a sundial. Neat, but not anal—that’s what you should aim for in a shrubbery.

Ophelia sure had the not-anal part down. The shrubs didn’t merely spread, they rioted. And what with the trees and the orchids and the ferns and the vines, I couldn’t begin to judge the border’s depth. The hibiscus and the bamboo were OK, although I wouldn’t have risked them myself. But to plant bougainvillea and poinsettias, coconut palms and frangipani this far north was simply tempting fate. And the statue! I’d never seen anything remotely like it, not outside of a museum, anyway. No head to speak of, breasts like footballs, a belly like a watermelon, and a phallus like an overgrown zucchini, the whole thing weathered with the rains of a thousand years or more.

I glanced at Ophelia. “Impressive,” I said.

She turned a critical eye on it. “You don’t think it’s too much? Rachel says it is, but she’s a minimalist. This is my little bit of home, and I love it.”

“It’s a lot,” I admitted. Accuracy prompted me to add, “It suits you.”

I still didn’t understand how Ophelia had gotten a tropical rainforest to flourish in a temperate climate.

I was trying to find a nice way to ask her about it when she said, “You’re a real find, Evie. Rachel’s working, or I’d call her to come down. She really wants to meet you.”

“Next time,” I said, wondering what on earth I’d find to say to a specialist on artificial intelligence. “Um. Does Rachel garden?”

Ophelia laughed. “No way—her talent is not for living things. But I made a garden for her. Would you like to see it?”

I was only dying to, although I couldn’t help wondering what kind of exotica I was letting myself in for. A desertscape? Tundra? Curiosity won. “Sure,” I said. “Lead on.”

We stopped on the way to visit the vegetable garden. It looked fairly ordinary, although the tomatoes were more August than May, and the beans more late June. I didn’t see any corn and I didn’t see any greenhouses. After a brief sidebar on insecticidal soaps, Ophelia led me behind the carriage house. The unmistakable sound of quacking fell on my ears.

“We aren’t zoned for ducks,” I said, startled.

“We are,” said Ophelia. “Now. How do you like Rachel’s garden?”

A prospect of brown reeds with a silvery river meandering through it stretched through where the Morrisons’back yard ought to be, all the way to a boundless expanse of ocean. In the marsh it was April, with a crisp salt wind blowing back from the water and ruffling the brown reeds and the white-flowering shad and the pale green feathery sweetfern. Mallards splashed and dabbled along the meander. A solitary great egret stood among the reeds, the fringes of its white courting shawl blowing around one black and knobbly leg. As I watched, openmouthed, the egret unfurled its other leg from its breast feathers, trod at the reeds, and lowered its golden bill to feed.

I got home late. Kim was in the basement with the animals and the chicken I was planning to make for dinner was still in the freezer. Thanking heaven for modern technology, I defrosted the chicken in the microwave, chopped veggies, seasoned, mixed, and got the whole mess in the oven just as Geoff walked in the door. He wasn’t happy about eating forty-five minutes late, but he was mostly over it by bedtime.

That was Thursday.

Friday, I saw Ophelia and Rachel pulling out of their driveway in one of those old cars that has huge fenders and a running board. They returned after lunch, the backseat full of groceries. They and the groceries disappeared through the kitchen door, and there was no further sign of them until late afternoon, when Rachel opened one of the quarter-round windows in the attic and energetically shook the dust out of a small patterned carpet.

On Saturday, the invitation arrived.

It stood out among the flyers, book orders, bills, and requests for money that usually came through our mail slot, a five-by-eight silvery-blue envelope that smelled faintly of sandalwood. It was addressed to The Gordon Family in a precise italic hand.

I opened it and read:

Rachel Esther Abrams and Ophelia Desirée Candarel

Request the Honor of your Presence

At the

Celebration of their Marriage.

Sunday, May 24 at 3 p.m.

There will be refreshments before and after the Ceremony.

I was still staring at it when the doorbell rang. It was Lucille, looking fit to burst, holding an invitation just like mine.

“Come in, Lucille. There’s plenty of coffee left.”

I don’t think I’d ever seen Lucille in such a state. You’d think someone had invited her to parade naked down Main Street at noon.

“Well, write and tell them you can’t come,” I said. “They’re just being neighborly, for Pete’s sake. It’s not like they can’t get married if you’re not there.”

“I know. It’s just.… It puts me in a funny position, that’s all. Burney’s a founding member of Normal Marriage for Normal People. He wouldn’t like it at all if he knew I’d been invited to a lesbian wedding.”

“So don’t tell him. If you want to go, just tell him the new neighbors have invited you to an open house on Sunday, and you know for a fact that we’re going to be there.”

Lucille smiled. Burney hated Geoff almost as much as Geoff hated Burney. “It’s a thought,” she said. “Are you going?”

“I don’t see why not. Who knows? I might learn something.”

The Sunday of the wedding, I took forever to dress. Kim thought it was funny, but Geoff was impatient. “It’s a lesbian wedding, for pity’s sake. It’s going to be full of middle-aged dykes with ugly haircuts. Nobody’s going to care what you look like.”

“I care,” said Kim. “And I think that jacket is wicked cool.”

I’d bought the jacket at a little Indian store in the Square and not worn it since. When I got it away from the Square’s atmosphere of collegiate funk it looked, I don’t know, too sixties, too artsy, too bright for a forty-something suburban matron. It was basically purple, with teal blue and gold and fuchsia flowers all over it and brass buttons shaped like parrots. Shaking my head, I started to unfasten the parrots.

Geoff exploded. “I swear to God, Evie, if you change again, that’s it. It’s not like I want to go. I’ve got papers to correct; I don’t have time for this” —he glanced at Kim—“nonsense. Either we go or we stay. But we do it now.”

Kim touched my arm. “It’s you, Mom. Come on.”

So I came on, feeling like a tropical floral display.

“Great,” said Geoff when we hit the sidewalk. “Not a car in sight. If we’re the only ones here, I’m leaving.”

“I don’t think that’s going to be a problem.”

Beyond the copper beech, I saw a colorful crowd milling around as purposefully as bees, bearing chairs and flowers and ribbons. As we came closer, it became clear that Geoff couldn’t have been more wrong about the wedding guests. There wasn’t an ugly haircut in sight, although there were some pretty startling dye jobs. The dress code could best be described as eclectic, with a slight bias toward floating fabrics and rich, bright colors. My jacket felt right at home.

Geoff was muttering about not knowing anybody when Lucille appeared, looking festive in Laura Ashley chintz.

“Isn’t this fun?” she said, with every sign of sincerity. “I’ve never met such interesting people. And friendly! They make me feel right at home. Come over here and join the gang.”

She dragged us toward the long side-yard, which sloped down to a lavishly blooming double-flowering cherry underplanted with peonies. Which shouldn’t have been in bloom at the same time as the cherry, but I was growing resigned to the vagaries of Ophelia’s garden. A willowy young person in chartreuse lace claimed Lucille’s attention, and they went off together. The three of us stood in a slightly awkward knot at the edge of the crowd, which occasionally threw out a few guests who eddied around us briefly before retreating.

“How are those spells of yours, dear? Any better?” inquired a solicitous voice in my ear, and, “Oh!” when I jumped. “You’re not Elvira, are you? Sorry.”

Geoff’s grip cut off the circulation above my elbow. “This was not one of your better ideas, Evie. We’re surrounded by weirdoes. Did you see that guy in the skirt? I think we should take Kimmy home.”

A tall black man with a flattop and a diamond in his left ear appeared, pried Geoff’s hand from my arm, and shook it warmly. “Dr. Gordon? Ophelia told me to be looking out for you. I’ve read The Anarchists, you see, and I can’t tell you how much I admired it.”

Geoff actually blushed. Before the subject got too painful to talk about, he used to say that for a history of anarchism, his one book had had a remarkably hierarchical readership: three members of the tenure review committee, two reviewers for scholarly journals, and his wife. “Thanks,” he said.

Geoff’s fan grinned, clearly delighted. “Maybe we can talk at the reception,” he said. “Right now, I need to find you a place to sit. They look like they’re just about ready to roll.”

“Walpurgis Afternoon,” excerpted from Young Woman in a Garden © Delia Sherman, 2014