While The Amazing Spider-Man didn’t have too much in common with its Raimi-directed predecessors, at the core it was still fundamentally a Spider-Man tale—with power, responsibility, monsters, and coming-of-age angst. And keeping that in mind, there were certain themes we all recognized and re-explored with this new version of Peter Parker, Aunt May, and the rest of the gang. Now, which film handled which theme with more deftness or subtly isn’t really what struck me the most. It was one theme overall that these films have tackled altogether.

More specifically, it was how many times ordinary people catch Spider-Man when he falls.

Spoilers for Amazing Spider-Man ahead.

Perhaps this wasn’t so obvious with Sam Raimi’s first film; we hadn’t seen the web-slinger on screen before, and it was a post 9/11 world, one that was incredibly conscious of how New York City was portrayed. (Don’t forget, the World Trade Center was removed from the film entirely, and the initial teaser that showed a web strung between the two towers was immediately pulled from circulation.) That moment where Peter has Mary Jane in one arm and a bridge car full of kids in the other, comics fans might have been expecting a repeat of the infamous “Night That Gwen Stacy Died,” but the Green Goblin is foiled on two fronts: a barge is hurrying below to come to the rescue, and when all hope seems lost, civilians on the bridge begin pelting the supervillain with every heavy piece of trash they can get their hands on.

The message was anything but subtle to a 2001 audience. The line “you mess with one of us, you mess with all of us” seemed like an outstretched hand to every New Yorker who had suffered in the wake of 9/11. The fact that both Mary Jane and the hostage group survive is a harder, more pointed blow; Gwen Stacy may have died in the original comics, but in New York City, our New York City, we would never let our hero down when he needed us most.

You could have called it a reaction to the times and left it there, but then Spider-Man 2 hit screens. Spider-Man has to stop a runaway subway train, but it takes all his skills and his strength combined. When it’s over, it looks as though he might fall to his death, but hands reach out from broken windows and hold him fast. Peter Parker is borne like an ancient hero back through the train’s crowd and lain gently to the ground. When Doc Ock demands that everyone stand aside, the whole population of the car (and true to New York City, it is a wealthy diversity of people) step into Octavius’ path to guard their friendly neighborhood walking wounded.

He protects us, so we must protect him.

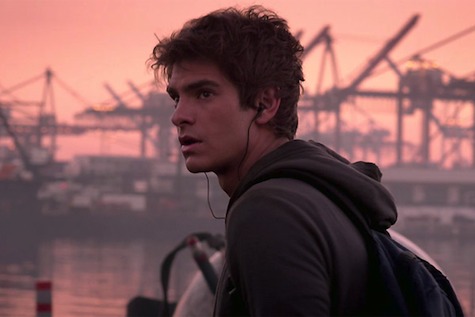

And while Spider-Man 3 was too much of a mess to add anything to the dialogue, The Amazing Spider-Man easily added its voice to this heartfelt trend. Spider-Man gets shot, and he’s not going to make it to Oscorp Tower in time to save the city. But one man remembers the debt he owes to the red and blue costumed hero: his son was saved by Spider-Man from a burning vehicle. So he gets every crane in New York lined up to give Spidey a clear path to his goal. And when Peter misjudges the distance he has to travel, that man is there to catch him when it looks like he might not make it to the next crane.

Much thought has been given to what permission we give to superheroes in comics. Alan Moore might be most famous for asking us all “Who watches the Watchmen?”, and it’s a question that needed to be asked, if the amount of scholarship it has provoked is any indication. If superheroes actually existed, the power that they could wield would likely be too easy to abuse. And most superheroes do what they do without asking if their help is called for: Bruce Wayne essentially makes himself the lone sheriff of Gotham, and the Avengers do not ask if they are doing more hurting than helping when they cause an estimated 160 billion dollars of damage to Manhattan.

But when Spider-Man is hurt, when he is weak, when he cannot make it on his own, we are always there to help. Even if the newspapers call him a villain and tell us we should shun him, even if the Mayor thinks that the way of showing our appreciation should be by offering him a useless key to the city. In essence, we are giving Peter Parker the permission to be our protector by taking on the responsibility that Uncle Ben always triumphed. If we want Spider-Man to be there for us, then we have a responsibility to be there for him.

What makes him so special, then? Why does Spider-Man command such personal devotion in his city? It could be because he is so very young. One of the most striking lines in Raimi’s films comes when the passengers of the train stare down at the unmasked hero, and one person from the crowd says what everyone is undoubtedly thinking: “He’s just a kid. No older than my son.” Peter Parker isn’t made of the big level drama that Tony Stark, Superman, and Captain America encompass; he’s just as likely to be there when you’re getting mugged as he is when some skyscraper is about to crumble. Spider-Man’s sense of justice is wrapped up in everyday, tangible things. Because he’s still in high school and he’s not a billionaire, and the safety of his streets are a real concern for him.

He doesn’t come with a moniker like “Invincible” or “Incredible.” He’s “Your Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man.”

And because that sensibility is something that we can all relate to, we enter a contract with Spider-Man that we simply don’t have with other heroes. In the latest film, before Captain Stacy tells Peter that he was wrong, that Spider-Man’s help is needed in New York City, he arrives to lend a hand right as the Lizard is taunting Peter for having no one. And the captain’s retort is more telling to us than it is to anyone on screen: “He’s not alone.”

Peter Parker is never alone because he has us. Because he’s not a dark knight or a super solider or an alien who’s faster than a speeding bullet. He lives around the corner from you, he goes to school, he’s a good kid. And sometimes he’s there to make sure that no one breaks into your house in the middle of the night.

So you better be there when he needs saving, too.

Emmet Asher-Perrin does think that Raimi’s Spider-Man had the better soundtrack. You can bug her on Twitter and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

The Avengers argument is silly. What’s the alternative? Let the invasion happen because fighting is too expensive? Who foots the tab when the invasion flattens the city and enslaves the populace? Who cares at that point?

Still, the crane scene in ASM is really good. Ever so slightly cheesy, but I prefer it to the train scene. Both are good, but for some reason, the cranes work better for me. I think it’s because it’s not followed by Doc Ock pushing the people aside anyway; the people just get their moment of triumph and it’s not stolen from them.

Of the first three movies, the saving of Spiderman after he stops the train is the scene I remember most and is my absolute favorite. Yes, we all have responsibility for each other, in Spidey’s world and our own.

@Tesh Yeah, the Avengers argument is kind of lame. “Oh, no! The lives of nearly everyone on the entire planet were saved at the cost of $160 billion! It’s too much! Take my life instead!”

I mean, seriously, the closest analogy we have for this kind of thing is an act of war. If, I don’t know, Denmark invaded New York, are we just going so say, “Ah, screw it, we’d blow up half the city kicking you out, you can have it”?

Beyond that, our friendly neighborhood government’s plan was to nuke our own city, which I think would have cost more (especially in lives lost) than the Avengers.

That was a lovely piece. And, not to get too Comic Book Guy here, it helps articulate why the death of Ultimate Spider-Man hit me so hard: no one was around to help him out. That seems like a betrayal of the character to me.

Peter Parker isn’t made of the big level drama that Tony Stark,

Superman, and Captain America encompass; he’s just as likely to be there

when you’re getting mugged as he is when some skyscraper is about to

crumble

While I agree with your general point as a description of Spiderman as characterised in these movies, I’m not sure I would agree that it’s as distinct from other recent superhero movies as this implies; the Plain People of Gotham very much get their moment of moral integrity at the end of The Dark Knight, to my mind.

The Spidey 2 subway* scene . . . well, didn’t make me weepy, but I was breathing deep and swallowing hard. It showed a respect for common people that you don’t find in many superhero movies.

There was a similar scene in Superman 2. When it looks like General Zod and company have killed Superman, a bunch of pissed-off Metropolian working stiffs pick up stuff and advance menacingly on the renegade kryptonians. I thought that utterly rocked. Those folks fully know what Zod and company are capable of, but are ticked off enough at the seeming demise of their hero that they go in anyway. (They are literally blown away, but props to them anyway.)

* Though seems more like a forgotten El that somehow survived into the Oughts.

P.S. What Emmet said about the Dark Knight. The criminals and decent folk alike show they aren’t the cowards and sheep that the sociopathic Joker imagines them to be.

Emily,

I just cannot let your comment of soundtracks go. True its an opinion and so now i must share mine

Comparing danny elfman to james horner it cannot be done. Elfman has the edgy modern classical whilst horner is classical thru and thru but still capable of fitting his score to the genre at hand.

Comparing elite composers just cant be done. Im all for bashing and smashing hans zimmerman but john williams and howard shore and i think ive lost my point in the swirl and rhythme of wonderful music…

@1 and 3 – Well, I think that actual argument to be made there is “the Avengers might have offered their help to the US army and people whose job it is to actually protect us rather than going off and making the decisions on behalf of everyone in the world.” It’s not quite a black and white situation there. There’s also the fact that the Avengers were likely (I’d say definitely in the Hulk’s case) responsible for crushing a fair amount of civilians while they took down alien threats, considering how many skyscrapers were taken apart.

I’m not saying that I actually care about that in the context of the film, because I was just as happy to watch them take the Chituari apart. But if we’re going to have a logical disucssion about it, there’s a heck of a lot to discuss….

@@.-@ – Ouch. Yes to all about Ultimate Spider-Man. That just hurts.

@5 and 6 – I agree with the comment about TDK to an extent – my feeling on it is that the people of Gotham are not specifically intending to help Batman fight crime in that moment. They are standing on their own against the Joker, and I doubt the man who made the choice to throw the remote out the window was thinking “On behalf of Batman!” as he did it. So I agree in terms of emotional resonance, though I’m not sure the situations are exactly the same in theme. Of course, arguments can be made for how Batman is subconsciously affecting Gotham, so I guess it’s easy to go back and forth on this one…

@7 – Hey, I love me some James Horner. I love every composer you named there, in fact. But while you can’t compare Elfman to Horner in terms of musical style and training, you can compare them as soundtrack composers. Personally, this was just not my favorite Horner score, and I felt that the Elfman theme captured the feel of Spider-Man better than Horner’s theme. It’s entirely opinion – one’s reaction to soundtrack music is usually entirely instinctual, at least it is in my case.

“Well, I think that actual argument to be made there is “the Avengers might have offered their help to the US army and people whose job it is to actually protect us rather than going off and making the decisions on behalf of everyone in the world.”

— not practical, in the context of the situation as outlined in the film. No time.

More broadly, serious fighting in a densely populated area always means civilian casualties, usually fairly massive ones — and that’s without WMD. Take a look at what a WWII-era city looked like after some intensive urban combat. Or Seoul in 1951, or for that matter Falluja more recently.

It’s a cost of doing business. You try to minimize collateral damage, but winning and minimizing your own force’s casualties come first.

This is a really nice article I enjoyed reading it, it has definitely made me realise that the “You mess with one of us…” line in the original Spider-Man movie isn’t quite as vomit-inducingly cheesey as I thought, given the context of the 9/11 disaster. I still don’t like it, but I get it.

With that said…

The ‘Subway Scene’ in the second movie and the ‘Crane Scene’ in this new film just make me want to claw at my face. They are completely over sentimentalised and incredibly unrealistic.

One of the previous commentators mentioned the angry mob going after Zod and the gang in Superman. Now that is a situation with a tinge of realism to it, when facing oppression and even overwhelming odds you can always rely on people to get angry, form a mob, and smash stuff.

Or what about the second film in Nolan’s Batman trilogy, where ordinary people dress up as Batman and go hunting bad guys, vigilante-style, with shotguns. How does that end? With one of them getting tortured and strung up by the neck by The Joker.

I appreciate the new Batman trilogy has a maturer theme throughout (and probably a higher Age Cert.) but if the makers of Spider-Man cannot include Joe Public in the film without a tinge of realism or without making me lose my lunch all over the cinema, then they just shouldn’t bother including those scenes.

At the end of the day I don’t think (though I’m sure a comic book expert will call me out on this) Spider-Man ever relied on the public in the comics or the cartoons. In fact I’d probably go as far to say he was much maligned by most of the public (and the police.. and the media..). Instead Peter Parker found most of his support (indirectly) from his Aunt and his friends… and… of course… from Uncle B ;)