Chabi doesn’t realize her martial arts master may not be on the side of the gods. She does know he’s changed her from being an almost invisible kid to one that anyone—or at least anyone smart—should pay attention to. But attention from the wrong people can mean more trouble than even she can handle.

Chabi might be emotionally stunted. She might have no physical voice. She doesn’t communicate well with words, but her body is poetry.

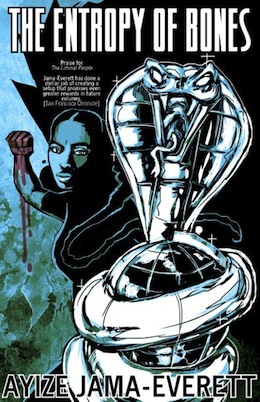

Ayize Jama Everett’s The Entropy of Bones is available August 25th from Small Beer Press! This spellbinding novel shares a setting—the present day, layered with magic—with Jama-Everett’s The Liminal People and The Liminal War, but it stands well on its own.

Chapter One

The Time I Choked Out a Hillbilly

Last time I’d been this deep in the Northern California hills I was on a blood and bar tour in a monkey-shit brown Cutlass Royale with Raj. Now I was distance running from the Mansai, his boat, to wherever I would finally get tired. From Sausalito to Napa was only sixty or so miles if I hugged the San Pablo Bay, cut through the National Park, and ran parallel to the 121, straight north. About a half a day’s run. Cut through the mountains and pick up the pace and I could make it to Calistoga in another three hours. From downtown wine country I’d find the nicest restaurant that would serve my sweaty Gore-Texed ass and gorge myself on meals so large cooks would weep. The runs up were like moving landscape paintings done by masters, deep with nimbus clouds hiding in craggy sky-high mountains. Creeks hidden in deep green fern and ivies that spoke more than they ran.

Narayana Raj had taught me in the samurai style. You don’t focus on your enemy’s weakness; instead, you make yourself invulnerable. My focus was to be internal. In combat, discipline was all. But in the running of tens of miles, that discipline was frivolous. My only enemy was boredom and memory. Surrounded by such beauty, how could I not split my attention? Nestled in the California valleys, I found quiet, if not peace.

I also found guns. Halfway between Napa and Calistoga, the chambering of a shotgun pulled my attention from the drum and bass dirge pulsing in my earbuds. The woods had just gone dark, but my vision was clear enough to notice the discarded cigarette butts that formed a semicircle behind one knotted redwood. Rather than slowing down, I sped up and choke-held the red-headed shotgun boy hiding behind the tree before he had time to situate himself, my ulna against his larynx, my palm against his carotid. He was muscular but untrained. Directly across from him was an older man, late thirties, dressed for warmth with one of those down jackets that barely made a sound when he moved. His almost Fu Manchu mustache didn’t twitch when he pulled two Berettas on me. I faced my captive toward his partner.

“Wait… ,” Berettas said, more scared than he meant to sound.

Drop them, I commanded with my Voice. The gun went down hard. I used the Dragon claw, more a nerve slap than a punch, to turn the redhead’s carotid artery into a vein for a second. When he started seizing, I dropped him. To his credit, Beretta went for the kid rather than his weapons. I continued my run, mad that I’d missed a refrain from Kruder and Dorfmeister.

As an indication of where my head was, I confess to not thinking about the scrap until a week later. Finishing the run, swimming ten miles a day, keeping the Mansai in shape, and avoiding my mother at the other end of the pier as much as possible, covered the in-between time. Even when I went back up the same route for my big run, the redhead was an afterthought.

It was only when I hit Calistoga, almost desperate for my calorie load for the run back to the Bay, that I had to deal with the consequences of my chokehold. I liked hitting up the nice tourist joint restaurants for grub when I was sweaty, and paying cash for double entrée meals. The place smelled of wood and fire, but most of the fixtures were constructed out of industrial iron and brass. Servers dressed in white shirts and black slacks prayed the heavy-fingered piano player’s jazz standards would cover the clang of their dropping silverware on the brass tables. Most patrons came in dressed in custom suits and designer dresses. Me, I’ve always been a sweats ’n’ hoodies girl. Usually I was the most out-of-place-looking person in the spot. But not that day.

I was devouring two orders of BBQ oysters, fries, and half a broiled chicken when a bear-looking man walked in. Seriously, he was 6’9″, three hundred pounds of muscle with another twenty-five pounds of fat for padding. He was local. I’d seen skinnier versions of his face in the area, long in the cheekbones, bullet marks where eyes should be. He wore a large red flannel shirt and Carhartts fit for a bear. But what stood out was his facial hair. It made a mockery of any other beard I’d ever seen. His hair started on his head and covered every part of his face, from pretty close to his eye sockets to well past his collar line. It seemed almost bizarre that a mouth existed under all that fur. But it made him easy to read. As soon as he saw me, the hair moved into a smile. All the waitstaff and bartenders seemed to know him. It wasn’t until he sat at my table facing me that I saw any relation to the redhead in the woods. I’m not usually one for weapons, but I palmed my butterfly knife on the off chance the bear tried to maul me in public.

“What do you weigh in at? One hundred and twenty pounds? Sopping wet?” he asked after it became obvious I wasn’t going to stop eating.

And you care because?

“I’m just wondering where all that food goes,” he said with a laugh. “What? You one of those bulimics or something?”

Mind not talking about gross shit while I’m eating? I snapped.

“Apologies. Didn’t realize you were so sensitive.”

The waitress delivered a slice of key lime pie and a glass of red wine so casually I knew she’d supplied the same to him dozens of times before.

That’s going straight to your hips, I said while shoving a handful of fries in my mouth. He laughed for a while before he could take a bite of pie.

“I knew this teacher, Filipino chick or something. One of those goody-goodies. Worked at a private school in Frisco. Coached soccer, taught all day, would drive up here and take dirt samples all around my vineyard, acres and acres. All for her thesis. She never broke a sweat.” He looked at me like I was supposed to get it. I kept eating.

“Turned out she had this hyperthyroid condition. Made her super strong, super fast, sped up her metabolism something fierce…”

Like a superhero, I said, laughing and chewing my chicken.

“Exactly,” the bear growled back. “Only if she hadn’t have gotten it fixed, it would have killed her.”

Believe me, I was listening for the threat. I stopped eating and stared the bear down. To his credit, he didn’t blink. But he didn’t keep eating either.

I get the sense you’re trying to tell me something, I said after I pulled my arms under the table.

“Then you misconstrue me entirely, young lady. I’m filled with nothing but questions.”

Better you ask straight away, then.

“Was that you that choked out my nephew not nine miles from here while his uncle stood by and watched?”

Your nephew the sort to chamber a pump-action on a jogger while she’s minding her own damn business?

“It took him two days to fully recover.”

But he recovered. I leaned back in my chair, spinning my knife to my wrist, ready for whatever came next. The waitress poured another glass of Syrah.

“My brother, the one with the mustache, said he’d never seen anybody adjust to a threat as quick as you did.” I nodded. “He’s been in Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan. But you impressed him. My nephew took a different path. Did six years in Angola—the prison, you understand, not the country. Another three in San Quentin before he got smart about his game. You got the drop on him, and he saw you coming. Now you eat like a horse, but aside from that you don’t say much, seem tough as nails and can obviously handle yourself. Type of business I’m in, I can’t help but ask if you’re looking for work.”

* * *

First time I met Narayana the entire pier was being threatened by snakes. Some idiot independent filmmaker decided he wanted to make a sequel of a movie that he didn’t own the rights to. He was shooting it “guerilla style,” meaning without a script, a proper crew, or a clue. Oh yeah, and it involved snakes on a boat. The majority of houseboats on our Sausalito pier were like the one I grew up in, more house than boat. You’d have better luck finding alcoholics and ’80s radicals living off the grid in those forever-moored houses than a sailor or anyone with a hint of grit in them. So when the pock-faced twenty-something filmmaker’s snakes escaped after a drunken wrap party, let’s just say things got chaotic.

Screams of panic didn’t rouse my mom from her drunken snoring back then. But I got curious. Not yet fully dark and all I could see were squirming shadows darting to and fro on the dock, in the bushes, out of people’s boats, falling in the water. Some of the snakes were thinner than a pencil and lightning quick; some moved so heavily across the port they seemed to dare you to touch them. Folks were grabbing their children and pets and locking themselves in their boats or trying to run past the snakes to get off the pier. I turned to go back inside when a coil hissed at me.

It was a hooded cobra. Don’t ask what kind, I wouldn’t be able to tell you. I just know it was banded, tan, and hissing. It stood between me and the walkway that went down to my houseboat. I tried backing up but in doing so I dragged my foot, a sound that agitated the snake. It raised its head a little more and hissed in a lower tone than I thought it would. What freaked me out more was that I thought I heard my name in its hiss.

I didn’t have time to focus on it. From behind me, a man five inches shorter than me and two shades darker appeared. His arms were so muscular and veiny they looked like a knot of rebar. But they were as skinny as his legs. What little hair he had was a deep red and mostly near his temples. He wore an Ice Cube Predator shirt and carried a large metal trash can. I couldn’t figure out which one I should be more cautious of: the snake or the man. He didn’t give me a choice.

“Hold this,” Narayana told me as he took the lid and handed me the can. With circular steps that never left the dock, the tiny man pushed lesser snakes out of his way with his foot until he was able to squat at arm’s length of the coiled cobra. What noise, cold, and chaos had been all around disappeared in the distance as I watched this stranger speak in angered tones to this snake in a language I almost understood. After a while, he seemed to get frustrated. So he slapped the snake. Hard. The snake hissed lower, I swear almost speaking. He slapped it again. It opened its mouth in time with the tides, methodically quickly.

Again, Narayana slapped its head. I didn’t see it strike. I didn’t see it move. But Narayana did. Faster than a bullet he raised the trash lid. The snake’s mouth made a harsh thud against it, but before it could fall to the deck, Narayana grabbed its head with his other hand. He stood with it as the snake’s body, more than double his length, flopped and fought. But it was useless; his rebar hands would not let go. He held it close to his face, staring in its eyes, and spoke to it in a thick accent.

“I’m free. Tell your masters.” He threw it hard in the trash can and slammed the lid on top. If he noticed me, he didn’t say anything as he grabbed the can from my hands. But I couldn’t forget him. Not ever.

* * *

The bear’s name was Roderick. His brother, Dale. His nephew was Matt, though I’d call him Shotgun forever. Together they ran a failing vineyard on one part of their property and a pot farm on the more secluded side. The side I’d been running through. They could have had a bed and breakfast on the property if they wanted to. It was gorgeous in that it was both spacious and hidden. Terraced rows of vines were what you could see from the road, but behind their three-story ailing farmhouse, dense tree growth hid acres of cultivated marijuana growing in clusters.

Roderick and Dale gave me a tour of the lands early the following week. They explained their situation as the gusty valley winds pushed earth and water to our backs. We paced rows of deformed vines of grapes as Dale spoke. Roderick would only reach his hands out and caress the plants like sickly lovers.

“We’ve got a plague of nymphs,” Dale’s half-humorous voice trickled out from under his mustache. “They are these almost invisible baby insects. They live in the roots and pervert the growth of the vines. Somehow they’ve encouraged the growth of this invasive tuber. Every time we think we’ve chopped it all away, the nymph-tuber combo comes back. They, well to be honest, they’re destroying us.”

“Fucking organic certification,” Roderick mumbled, kicking one of the many deformed pale gray vines out of his way.

“We don’t know the cause,” Dale snapped at his brother. “We just know we can’t use any inorganic pesticides to combat them. That’s how we came across our secondary income stream.”

Neither one said much more until we arrived at a giant red and gray barn with two massive doors far out of view of the freeway.

“It used to be a slaughterhouse for sheep when our grandparents bought the property,” Dale said by way of explaining the sign on the door: “Sheep’s tears.” I ignored it, more captivated by the smell. Inside the barn was a good 50 x 70 feet filled with rows of marijuana plants and PVC pipes. Huge floodlights hung from the ceiling and the plants glistened, refracting light like they were made of green crystals instead of whatever the hell makes up weed.

“What do you think?” Roderick asked.

I think your nephew better get that shotgun off me unless he wants to get dropped again, I said as I inspected the plants.

“God damn it!” Roderick yelled toward the roof. “Matt, you get your ass down here and apologize before I crack your fool jaw my damn self.”

Dale came to my side just as his brother mounted the stairs.

“Upstairs is the nursery. Originally we were going to use the oil from the plants as an insecticide. It’s been used for centuries as a…” I just looked at him. “Ok, so that was probably some wishful thinking Roderick and I used to get started. But then Matt got out of lockup with all these connections.”

“I’m sorry I aimed at you,” a shamed Matt said quickly as he came down the stairs. He said no more and instead rushed over to a large cistern and started misting the plants.

I’m not a smoker, I told the three of them later at the brass restaurant, which Dale was a part owner in.

“Can’t be with those lungs,” Shotgun Matt quipped.

I mean I don’t know any more about your product than what you’ve told me today. My mom would burn a blunt occasionally before she had her come-to-Jesus moment, but the bottle was more of her thing even then.

“We’re not asking you to grow the stuff.” Roderick the bear smiled.

“We need protection,” Dale said. I could see Shotgun’s ego shrinking up under his nut sack as I smiled.

Say more, I whispered, looking at Shotgun.

“Look, we got Mexican problems.” Shotgun spat out quickly so as not to offend the kitchen staff. “We’ve got ninety acres of farmland. Those plants you saw today are just one strain. We’ve got five patches hidden throughout the property. But these damn Mexicans keep coming through and stealing our crops. That’s why we were out in the woods when you came on us. Not only do we have to fight back bug blight on the grapes and tend to the others, we’ve got to scare off Mexicans.”

How do you know they’re Mexican? I asked, sipping tea.

“Huh?” Shotgun was confused. “What? I thought you were some kind of Asian or something…”

Yeah, Mongolian and Black. I’m not taking offense. You’re saying Mexican. All I’m saying is you know how?

“Who else would steal a man’s weed?” Dale smacked him in the head hard before I could react. Roderick put his calm voice on before speaking.

“Jail will do horrendous things to a man’s sense of reason. Look, we’re not looking for bodies. We don’t want a war. But we’re fighting for survival, literally. This year’s grape harvest is down thirty percent. Last year it was fifteen percent. Without those green buds, we’d have already gone under. All we need from you is to do…”

What I do best.

* * *

I’ve always wanted to sing but when I was born I couldn’t even cry. My mouth made the shapes, my heart mourned. But there was no sound. I should have been able to speak. I was healthy. I could hear fine; sure, I’ve always been light for my age, but it’s not like I don’t eat. My mother says I hit my social markers a little late. I was shy. That’s the understatement of the decade. I wasn’t shy, I was terrified. All it takes is four kids chasing you around a schoolyard trying to get you to do the one thing you can’t do to cancel all thoughts of education as a safe refuge.

I was on the boat experiencing what can only be described as multiple slow-motion mule kicks to my lady parts when I first got my Voice. My mother was not one to hold back anything so she told me what to expect with menstrual cramps. But her words did nothing to prepare me for the persistent Muay Thai jabs to my womb, or the splitting headache that was threatening to vibrate my teeth out of my mouth. Even the slow swaying motion of the ocean against the docked houseboat was enough to make me nauseous. I thought my body was going to split open, I thought something was wrong with me; this wasn’t the way it was supposed to be. I knew all of this period drama is pretty typical, but then there’s the added dimension of not being able to speak. Not being able to scream it out, or even cry it out. I wasn’t about to gain a voice just so I could complain about my period. Or so I thought.

“Girl, what you need to do is calm down and take this pill,” my mother told me when she came into my room, hazel eyes already flushed with irritation.

You don’t understand how much this hurts, I screamed in my mind.

“Shit, girl, you think this is bad, try childbirth. Now take this damn pill.”

Think you could bring me some damn water since I can’t stand up?

“That’s the only ‘damn’ I’ll be allowing from you today. Pull it together, Chabi. This is just the beginning of your womanhood,” she said as she left my room to get some water at the kitchen upstairs.

That was the first day I ever spoke without using my lips. I couldn’t really reflect on it, or even understand what happened until the pain meds kicked in, but even then I thought I was dreaming it.

It wasn’t until I was at school a couple of weeks later that it happened again. The fact that I couldn’t speak somehow meant that I belonged with kids that couldn’t hear. At the Marin County School for the Deaf I was a star among the students for being able to hear and still sign; I still found it the most oppressive environment in the world at age twelve. It didn’t help that I was the darkest, poorest, most four-lettered signing child that had ever crossed their path. My mother’s frequent temper tantrums on school grounds coupled with her inconsistent payments didn’t do much to endear me to the administration. There wasn’t much Mom could do about it. She worked as a hotel receptionist from the day my father left her. I had a three quarter scholarship; guess they didn’t have a lot of half-black half-Mongolians on their brochures. But that quarter was a bitch to get around for Mom. The hotel where she worked paid well enough, but the only place in the Bay where we could afford a two-bedroom was the houseboat, permanently docked and forever in need of repair. The end result: a mute, dark-skinned Asian-looking scholarship kid among the wealthiest white deaf kids in California. Tween social relations being what they are, compassion was a hard currency to come by. Even deaf bitches from San Rafael can throw shade on the playground. So when Callie Mills decided to trip me while playing a game of volleyball I wasn’t planning on doing any more than signing for her to fuck off. But I face-planted hard and nearly broke my nose. The pain and the anger triggered that Voice again.

Touch me again and everybody here will know why your dad shows up with a different chick every week, you skank whore, I thought-said-projected-felt, getting up from the ground and staring at her. Callie began putting her hands to her ears with a look of revulsion, almost unconcerned with me, and then stopped. She saw my gaze hadn’t shifted, and so did everyone else. Then the tears came. When you’re deaf and crying, it’s hard to be comforted: you can’t really read what people are signing to you behind a shield of tears. I didn’t care at the time. My nose was still bleeding. So I added fuel to the fire.

And you better stop telling people the only reason I’m here is because my mom gives the dean head or I’ll break your fingers. That was it, my first fully intentional “sentence” someone else heard. Her tears turned to panic screams as she threw herself on the court and began ripping at her ears. No one cared about my bloody nose after that. In fact, no one would look at me after that.

* * *

The job itself was beyond easy. The two weeks of waiting would have driven most people crazy, or, more to the point, drove Shotgun Matt nuts. His uncles demanded he follow my lead and I needed only flash a disconcerting look if he ever challenged my authority and the former con stepped in line. I surveyed the land and walked the five fields of marijuana a few times in silence before I found the only spot on the property, about one hundred feet behind the nursery, where I could either see, hear, or feel each of the plots. Unfortunately for Shotgun, it was near a nest of deformed nymph growth that smelled… particular.

It looked like a mushroom decided to molest a grapevine, and the grapevine was fighting back. Every time Roderick and his brother hacked at it, the growth just spread its fleshy purple, green, and white phalanges out farther into their property. Left alone it grew in a semicircular pattern around a huge boulder, creating an almost throne out of the stone that gave off the scent of crushed grape, mashed mushroom, and some foreign incense. It worked for me but I think the smell drove poor Shotgun crazy. It was a constant reminder of how and why his mostly legit family was growing criminal crop.

If that wasn’t the cause for his lunacy, maybe it was my stillness. My routine was to hang at the Mansai until around three p.m. Then I’d run the seventy-ish miles to the farm. I run faster at night so I’d usually make it around 12:30. Dale would just be coming off his guard/tending shift. A large plate of food would be waiting in the nursery: usually a full roasted chicken and mashed potatoes. After a genuine effort to get me to share more about myself, Dale’s fatigue would get the better of him. To keep him quiet I’d take the jacket and sleeping bag he offered. But it was my katas that kept me warm and alert. By two in the morning, I’d be so energized and focused that a once-over of each weed plot on the property took a total of ten minutes. Then I’d sit on the nymph rock, focus my breathing, still myself, and train myself to notice the exact moment when night turned to dawn.

That would be when Shotgun showed up, namesake in one hand, microwaved breakfast sandwich in the other. I knew my senses were sharp when I recognized the ping of his loose muffler a quarter a mile down the freeway. Frustration would set in the second he was done tending to the plants. He seemed surprised to not be allowed a headlamp to read. He didn’t know how to just sit and wait.

“In his defense,” Dale told me after he took over his nephew’s shift, “he was locked up for a while. I think the young man has had enough of waiting.”

I’ve had enough of excessive sighing and tantrum page turning, I said, looking down from the rock to where the older man sat. His dark plaid jacket was only slightly zipped so I saw the strap of his holster. His weapons of choice, the twin Berettas, were constantly with him.

“I’ll do my best to make up for my family’s inadequacies, my lady.” Only a gay man could flirt with a woman so casually. But it was his measured reasoning I appreciated above his flattery. Dale sat quiet, always awake, and always alert. But he was never excessive in his concern. His nephew carried a shotgun and held it like he was under enemy fire. Dale concealed two weapons with illegal hollow-point rounds but would only reach for them if he knew it was time to bring the pain.

I sat and imagined the stories of the nymph growth. I’m not prone to fancy but the growth fascinated me. I’d looked up the word “tuber” and eventually Wiki-trolled my way to the term “rhizome.” The idea of an underground growing mushroom/potato that could have been growing for hundreds if not thousands of years resonated with me. It made the idea of trees, growing upwards searching for a sun they could never reach, seem arrogant. The rhizome stayed underground, quiet, growing out instead of up, growing with whatever was around it instead of pulling from around it to break through the very earth. Here was an unseen, quiet changer of fortunes that represented massive amounts of power. If I sat long enough, still enough, it encroached on my lap. If it was truly as pervasive as Roderick swore, then it ran underneath all their property, spreading in its haphazard fashion, choosing other growth to interact with at random. I felt/imagined the white thin tubers interacting with the roots of the large spruce Dale rested on early one morning. In that connection, the growth knew all there was to know about Dale: how he’d been discharged from Naval intelligence because a hated subordinate found him in bed with his lover. How Dale evened the score by guaranteeing the subordinate would never advance beyond the rank of yeoman. How he worked in private intelligence in Yemen, South Korea, and Pakistan for five years until he realized the information he was securing was open to anyone willing to pay. Anyone. How he left it all, bought into the restaurant in his hometown, and worked this vineyard with his hunter/hippy of an older brother and tried his best to care for his dead sister’s kid.

The knowledge came without asking and was in no way verified. But it was felt, like when I got a kata right or when I was in perfect running stride. I didn’t even focus on the man; the knowing came just by keeping my senses open, like the knowing of the weed stealers.

Seven on the ridge two and a half acres away, I said after almost two full weeks of sitting. As expected, Dale was up with both Berettas in hand before I even knew what I was saying. I witnessed the statement coming from my non-mouth with my Voice in the same time that Dale heard it.

Wait, I told him as I stood. Call your brothers in now and we’ve got war. I’ve got this.

“You’ve got seven, possibly eight guys?” he asked, already following behind me as I ran in the early morning light toward the southeastern field.

If you stay quiet, yes, I whispered.

I cut into the dense pine that hid a half-acre of weed plants and disappeared up a tree before Dale could protest. I heard his feet shuffle on the soft ground as I did my first Tarzan leap from one tree trunk to another. But Dale did right and took cover where he was. By my ninth jump I’d perfected my technique so I didn’t shake the receiving tree at all.

The marijuana plants were planted less in rows and more in concentric circles, navigating around all sizes of sage bushes, berry patches, and large pines. Shotgun was partially right: three of the seven were Mexican; the rest were white. Locals, if their accents were to be believed; all of them had guns. I waited until Dale came in range with his weapons before I made my move. That gave them time to spread out. They were disciplined thieves, snipping buds in teams of two. It was only good fortune the terrain was with me. With all of them desperately snipping, no one noticed my descent from the massive sequoia. I choked the first one out in between clippings. His partner only noticed a prick on his neck, then he was out. I signaled to Dale to grab their guns, then moved to the next two, who harvested closer to a thick raspberry bush out of view from the others.

I let the large Mexican see my fist and when he raised his thick Adam’s apple to speak I shoved it into his mouth. Falling on his knees caused such a thud his partner had to look over. All he saw was my head-butt causing three grand in dental bills. The last three were closer now. It would have been easier to play it straight but I wanted the challenge. I gathered three stones, half palm sized, and launched them in the thieves’ direction. All three hit, but only two went down. The last, another local, twirled, confused by his own pain and fallen friends. I pounced on him quick, covering the distance between us without regard to sound, and finally choking him out with a hush.

All good? I asked Dale as he came up from the berry bushes holding the guns of the others. His breathing was even but his eyes were wide. Before he could say anything I went around salamander-smacking the small of the thieves’ backs, keeping them both paralyzed and unconscious. That snapped Dale back into business mode and he began searching wallets.

* * *

“Walking up hills both ways again, huh?” was what my mom said when she heard about me getting kicked out of school. I didn’t help my case by telling her I wanted to go to a normal school. I couldn’t figure out how I was “speaking,” but it was all I ever wanted and I wasn’t trying to question it. I did my best begging impression to Mom in her room, the loft section of the houseboat. She was seeing what I was trying to demonstrate to her. Namely that somehow I was speaking. I could see her trying to logic out what was happening, why I’d been going to the deaf school in the first place, but every time she got close to an answer, her deep red forehead would smooth, her forever light-purple-stained lips would cease their endless dance, and her chest would relax. After that, whatever acknowledgment of my former state disappeared. It was like she never even knew I was mute in the first place. She looked… into me, trying to see what was missing, what she couldn’t understand. I would’ve tried to help her, honestly. If I had any clue myself.

“You want to go to public school, you’ve got to learn how to fight.” To her credit, Mom grew up in East Oakland in the crack era. For her, public school and fighting went together like wine and bottles.

Got it. I knew the perfect teacher.

* * *

Narayana began taking notice of me after the snake incident. He’d taken on a bit of hero status around the pier. I was just one of his rescues. He’d gone into people’s houses with a machete and diced snakes. Apparently he also had some violent words with the “director” as well. But it wasn’t his violence I was after. It was his eyes: eyes that could stare down a cobra and not flinch. I caught a glimpse of that stare and I wanted to adopt it.

He’d only spoken to me one time since then. Mom was looking at a DUI, and while she was able to avoid Marin’s finest, her seat belt and car door got the best of her entangled and suspended as she tried to get out of the car. I heard her in the parking lot attached to the port, a good two hundred feet from our front door, screaming and cursing up a storm. I went out to help her and had to deal with her wild swings and violent sobs. At the scrap of grass in the middle of the cement parking lot, probably intended to be something more than a place for houseboat dogs to shit and piss, Mom’s meaty breast slipped out of her dress. I tried to help but then she fell. I was able to get her to her feet again, but was losing her when Narayana appeared, again out of nowhere, and grabbed her other side. She struggled against him, but only for a second. He dragon-clawed her, but in a gentle way. She seized for a second and then passed out. I didn’t have voice at the time to say anything. Instead I watched as he took all her weight and carried my mom back to the house. He put her in the bed without a word. It was only when he left that he spoke, voicing his phone number, and waited until I nodded acknowledgment.

“Ever again, you call. No one talk? I know you. I come.” And once again, he was gone.

* * *

There’s a feeling you get when someone really hears you, you know? You can do all that eye contact, attentive body language stuff, but if you’re not paying attention, people really know no matter what you do. I seemed to be able to force that attention, to make people pay attention to me. And that attention was so strong, people understood what I was saying, thinking… something. But when I tried to use the phone, the illusion failed. It felt like a mental trick played on me by the world.

I ran out the house in my Crocs and the clothes I slept in, a pair of jean shorts and a gray wife-beater a size too big. I ran over to the Mansai, the authentic old-school twenty-five-foot hunk of junk with more power than a small brown man was supposed to be allowed to have in this country. Narayana terrorized the clueless and novices alike in the S.F. bay with that ship when he first docked in our harbor, but after a few months he seemed happy to just have its menace on the waves as a potential threat.

The afternoon cold was beginning to roll in but Narayana stood on his deck shirtless with the snake-destroying machete and sliced paper-thin sheets of watermelon, not nicking the deck in the slightest. He thought weighing more than one hundred and ten pounds was a sign of American gluttony and on his 5’3″ frame, he was probably right. Even though he rubbed cinnamon oil on his arms and legs every day, his skin still seemed slightly ashen to me.

Cool, I said once I realized what he was doing.

“It’s practice,” Narayana said amiably, right before he did some wild overhand right swing with a machete, and delivered a pancetta-thin slice of watermelon this time to my nose. “I have little caramel downstairs. In between slices tastes good. You want?”

The slice was in my belly before half his sentence was done. Narayana just laughed at me.

My mom says I can go to regular school, I said tentatively suddenly frightened of what would happen if Narayana stopped “hearing” me.

“And why shouldn’t you?” he said after another slice. I looked up in delight to see him judging the slice with his eyes closed. He let the edge of the blade roll up and down the light green of that watermelon with his machete, never far away from him. That blade was sharp, but the machete was nothing special, just a farm implement. With that blade, he recorded every ridge, bump, and crease of the fruit. And once he memorized those indicators, Narayana once again chopped a leaf of watermelon off the fruit with an overhand right and would not nick his deck. Only this time he his eyes were closed, and he sent the slice directly into my face. I caught it half with my hands and half with my mouth. The fruit was almost gone by the time he opened his eyes.

But she says I can only go if I learn to fight. He was halfway through another blind swipe when Narayana froze and broke posture entirely.

“Why me?” he asked. I took his help onto the deck and looked at the man as though he were feverish.

Um, not a lot of Indian men I know spend their afternoons chopping fruit with machetes. Or call it training. He smiled and sat on his ever-present cooler. It was attended to with religious fervor, never to be absent of its holy sacraments of Jack Daniel’s and Coca-Cola. Sometimes I think those two ingredients were the only spices to his life the United States offered Narayana.

“But why do you want to practice for what I am practicing for?”

Because no one fucks with you and you don’t even know it. I have never seen you nervous or out of your depth. Ever. I still remember when that group of yuppies almost crashed into you out by San Rafael and how you went all pirate and jumped on their ship. Yeah, that right there. I gotta learn how to carry myself like that.

“You want to hijack ships?” he asked in earnest. My mom told me he used to be a pirate. I thought it was a joke until I looked online and found out booty was still getting plundered and cannons were still being fired on the open seas. Only now it was the poor, the desperate, and the insanely brave who dared become pirates. I saw Narayana differently after that.

No. But I want people to know I can and will in a second if the situation calls for it. I want to be like you.

Something about the reflection of the light from his blade to his face made Narayana look menacing in that moment. He saw me flinch and let the machete down on the deck gently. He turned and went to his ratty green-and-yellow lawn chair and poured himself a Jack and Coke. He offered me one, but I declined. That earned me a little more respect in his eyes. Still, Narayana sat and watched the sun go down behind San Francisco before he said anything in English.

“You do what I say? Everything. Anytime. Never a ‘no’ from you to me. You become mine. I lend you to your mother. If she’s drowning and I’m drowning, you save me. I don’t recommend this path for anyone, being under me. Go find a dojo, something like that. They teach you how to fight good.”

That I had to think about for a second. Was good good enough?

What’s the difference between some dojo guy teaching me and you? Like what’s your style? You do kung fu? Tae kwan do?

“There is no name to what I know,” Narayana said, taking a long sip from his cup. “Kung-fu, your muay Thai, these arts teach you how to break bones. What I do breaks the memory of bones. People do not heal from the wounds I inflict. There is no humanity in what I teach, only fire and sharp flexible pain. I travel the world for sixty-eight years, and this is the only discipline that makes me humble before it.”

Get the fuck out of here. I laughed. My mom was thirty-three. Narayana looked maybe five years older than her.

“The practice,” he said, showing off his taut skin.

Excerpted from The Entropy of Bones © Ayize Jama-Everett, 2015