Welcome back to the replay of Chrono Trigger! Last time we covered the destruction of Zeal, and ended with your first major battle with Lavos…

It’s a trope that the older we get, the more we fear death. All these years later, Crono’s death during that first confrontation with Lavos still shocks me. Usually, the repercussions of any gaming death are easily fixable with a continue or extra life. He’s the main character. He’s not supposed to die, right? But no, Crono was really dead. For a silent hero, Crono’s actions sang volumes just by his willingness to sacrifice himself without a moment’s hesitation. Even Magus, the arch villain until that point, appears shocked. And if you’re strong enough, you can go fight Lavos again without Crono and beat the game.

Originally, Chrono Trigger writer, Masato Kato, wanted to keep Crono dead. To continue the mission, the party would actually have to recruit a younger version of Crono. But Square deemed it too depressing and requested that the rest of the story be written in a way that he can still be saved. Depending on your perspective, the next sequence was either the most intriguing rescue mission devised, or the cheesiest part of the game. The characters use a time egg to initiate the eponymous “chrono trigger” and save Crono’s life. I really liked it and even if it was a bit deus ex machina, I thought it was a clever use of time travel, though it did make me wonder, if they could freeze time like that, why not also kill Lavos in the process?

It’s after this point that Chrono Trigger essentially becomes open world and open time. You can go anywhere, anywhen, and undertake multiple sidequests. It’s one of my favorite parts of the game because many of the adventures are character-driven segments that reveal more about your party members. I also appreciated how every decision you make impacts the ending and the way the quests play out. If anything, it’s an allegorical representation of time with all its branching pathways.

The Second Trial and the Origin of Robots

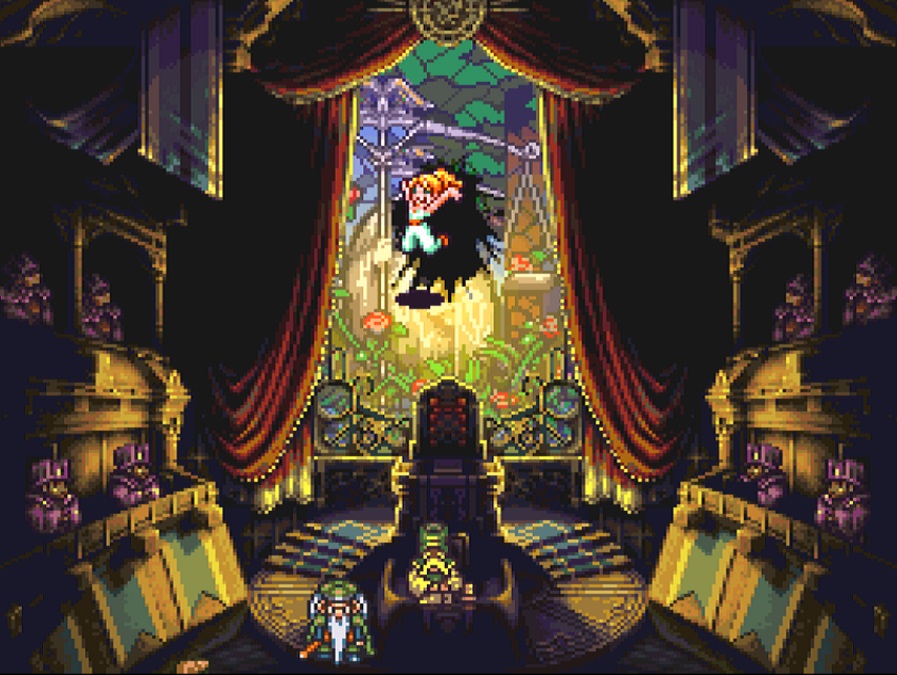

Almost every character gets a subquest, and my favorites were those involving Marle and Robo. In the first part of the retrospective, I wrote about how much I enjoyed the trial sequence. I didn’t know there was actually a second trial and it was Marle’s father, the king of Guardia, who was put in front of the jury. Accused of stealing a rainbow shell, a powerful relic that could be crafted into the best weapons, the trial only happens if you find it in the past and leave it with the king of Guardia at that era for safeguarding. In that sense, you’re responsible for the judicial woes of the monarch in the present. While the trial is short lived (you prove his innocence in a race against the clock), it leads to a touching reconciliation between Marle and her father—they’d been alienated since her mother’s death. Marle crashes through the stain glass window above the court room in an action scene befitting her character; it shows how she goes against the traditional mold, breaking sacred rites to do what is right, consequences be damned.

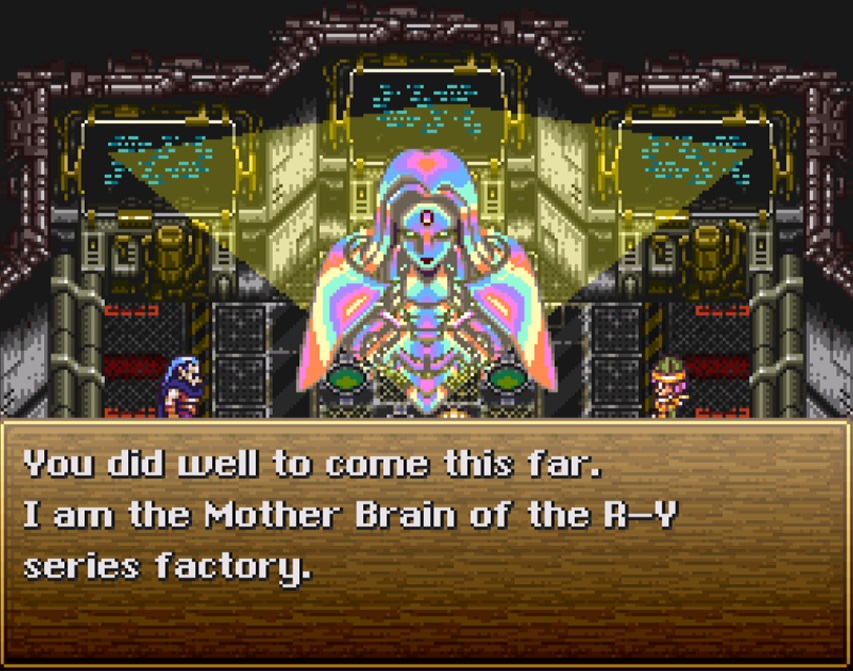

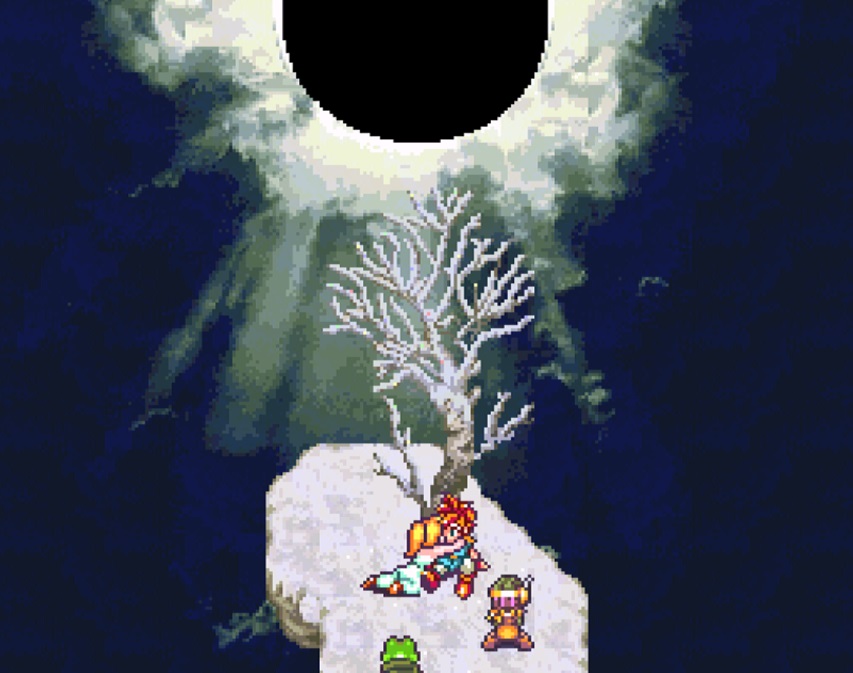

There are also two sidequests in which Robo plays a key role. The first involves a desert bereft of plantation, which he spends four hundred years reforesting. It’s one of the most graphic representations of your team’s effect on time, visually altering the map and giving life where there was none. His efforts take on an even more tragic light considering that in a few hundred years, his work would be rendered futile by Lavos’s awakening. Robo’s more despondent sidequest involves discovering his true identity in the apocalyptic future. His actual designation is Prometheus, and under his original programming Robo was to live among the humans, study them, and bring back the knowledge to the other robots in order to make the remaining people easier targets. It seems like the ultimate betrayal, a Terminator-esque twist, until we find out the future is much more complex than we’d thought. Lavos is still alive, and his children will eventually need to feed. “This world COULD sustain them…if humans were not around,” Mother Brain states. If humans continue to survive and consume Earth’s resources, Lavos would have no choice but to start sending out Lavos seeds to other planets. As Mother Brain sees it, the destruction of humanity could potentially save other worlds, since it would give Lavos no reason to leave.

Even though we had to take Mother Brain down, I couldn’t help but feel regret and sorrow. To Mother Brain, this made sense and was carried out after logical analysis pushed her in this direction. The machines could coexist with Lavos, even creating their own utopia, but the humans could not. The anthropocentric perspective is the only thing that justifies your annihilating the mechanical force, similar to the way you destroyed the Reptites in the past. Are we the good guys only because we’re human?

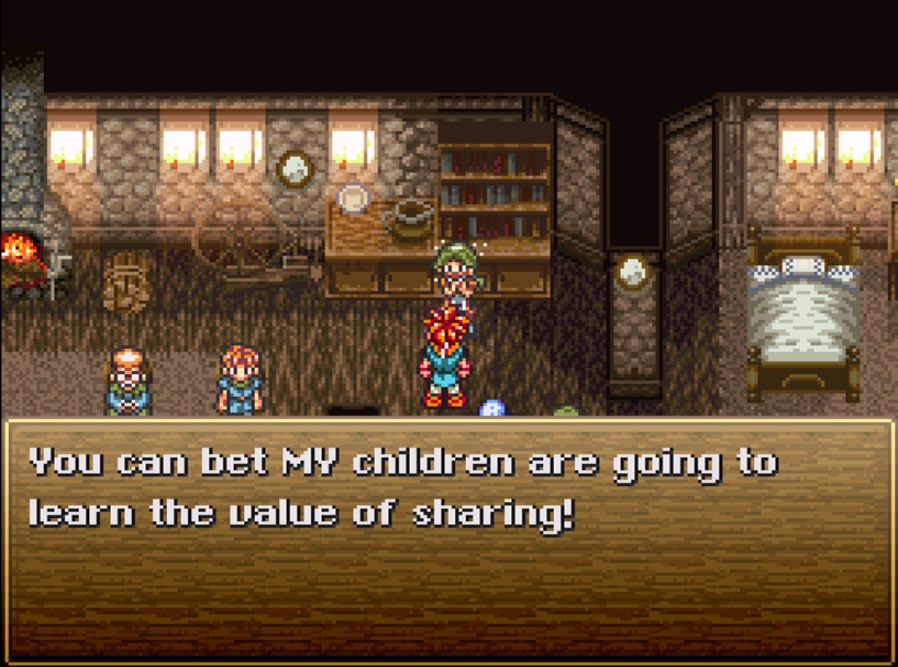

One of the most wry commentaries on human nature happens in the moon stone quest. You’re trying to re-energize the rock over several million years so that you can wield its power to create some rare weapons. It’s stolen in 1000AD and you track it down to the mayor of Porre, a miserly scrooge whose own family can’t stand him. He uses his money to make a mockery of those around him and even offers you ten gold to dance like a chicken. If you go back four-hundred years, meet the wife of the then mayor (the greedy one’s ancestor), you can change destiny with a simple gift. She loves jerky and when she finds out you have some, she offers you money in exchange for it. If you generously offer it to her for free, she’s so touched by your kindness, she promises to teach her children to be just as giving. When you jump back to the present, the mayor will hand you back the moon stone without requiring anything in exchange. On top of that, his family loves him for being so gracious and he seems an overall happier man. One act of kindness had huge repercussions throughout the generations.

(As a bit of an aside, the whole scene reminded me of a point I saw highlighted in Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises versus Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies. Both films cover the devastation wrought on Japan during World War II. But whereas Miyazaki’s ultimate message is of hope, Takahata’s is one of despair in The Kingdom of Madness and Dreams Miyazaki himself speculates how different each filmmaker’s work would be had they had different past experiences.)

If there’s two complaints I had about the final sequence, it’s that neither Ayla nor Crono get a special sidequest. I would have expected Ayla to have some kind of backstory with Kino. And despite Crono being the silent hero, I would have really enjoyed finding out more about who he is, what his relationship with his family is, and why he likes cats so much.

Cats are the Secret Rulers of Chrono Trigger

There are cats everywhere in Chrono Trigger. If you return to the ruins of Zeal in 12,000BC with Magus in your group, Janus’ cat Alfador will follow you around. And in Magus’ sidequest involving Ozzie and company, a cat will actually help you vanquish them. Cats have apparently won their secret war with dogs, as there are no canines present throughout the entirety of Chrono Trigger. We can even speculate that just as dogs really run the world behind Silent Hill, it’s very well possible cats are pulling the strings and their real goal is to let the humans get wiped out by Lavos so they can take over. Sorry, robots.

Yasunori Mitsuda

I’d be remiss in writing a retrospective/replay without mentioning Yasunori Mitsuda’s brilliant soundtrack. There was a period of time when I had heavy insomnia and the only thing that would consistently put me to sleep was the first CD of the 3 CD OST of Chrono Trigger. I know those tracks both consciously and subconsciously as my sleep patterns were intertwined with their melodies. Mitsuda himself, who often slept at his studio, stated that several of his dreams were inspirations for his music. He specifically did not want his tracks to fit into a genre, instead, drawing on personal themes. There’s a quality to each of them that reminds me of a reverie, a timeless sense which is part of their appeal. This ranges from Frog’s theme, streaming with nobility and loss, to Crono’s brave and bombastic track, to the intangible tragedy and intricacy of Schala’s chorus. Unfortunately, Mitsuda suffered a devastating loss when forty in-progress tracks were lost after his hard drive crashed. The stress might have been one of the factors resulting in his stomach ulcers, and he eventually needed help from Final Fantasy maestro Nobuo Uematsu to finish it up. How different would the game feel if those forty tracks had survived? Would there be any significant changes?

I wonder if there is a corresponding library for musical composers like that in Sandman for books that exist only in dreams.

Choices

One of the most innovative features Chrono Trigger gave players was the New Game+ feature, which let you restart the game with all your powers intact. You didn’t have to worry about level-grinding and could instead focus on changing history to get one of the multiple endings (thirteen when I last checked, but there could be more on the DS remake). Depending on when you defeat Lavos, you’ll get a very different universe as a result. If youbeat the game before you kill the Reptites, for example, you will usher in a new Dino Age where everyone is reptilian.

This type of freedom can be both liberating and upsetting—liberating in that you can go and do whatever you want to get a unique experience; disturbing in the sense that you might not get the complete experience. As more and more games have so many variables with different players getting divergent results, this is less like a film, where interpretation defines the experience, and more like having a unique scenario play out depending on player choice. Chrono Trigger uses this mechanic to its advantage with the New Game+ that encourages multiple playthroughs and further exploration.

But on some of the modern RPGs, they’re so vast, I feel compelled to consult FAQs and strategy guides to make sure I don’t miss anything significant even though I really don’t like using them. Chrono Trigger’s sequel, Chrono Cross, is full of instances where a “wrong” decision will prevent a given character from joining your team for the rest of the game. I can think of several contemporary games where I missed big story points other gamers raved about because of different choices I’d made. In this case, it’s more a reflection of how eager I am to experience all the main storylines of a game rather than a critique in itself of the genre. I can’t blame a given title for being too grand. In fact, I relish in the knowledge that my decisions actually impact the storyline and often live with choices that resulted in heartbreaking consequences (Dragon Age, Heavy Rain, Mass Effect, Witcher II, and Suikoden II come to mind). The potential for multiple narratives intertwining in manifold directions spurred on by the player was almost perfectly executed in Chrono Trigger, remarkable considering it came out over twenty years ago. It’s no wonder it’s considered one of the greatest games of all time.

In many ways, games were my myths growing up, the narrative language that helped me to bond with other players across religion, ideology, and race. Games like Chrono Trigger were my universal translator, the cross-cultural myth I shared with almost anyone who played it. I just wish there was a New Game+ for real life.

Peter Tieryas is the author of United States of Japan (Angry Robot, 2016) and Bald New World (JHP Fiction, 2014). His work has appeared in Electric Literature, Kotaku, Tor.com, and ZYZZYVA. He travels through time at @TieryasXu.