“I have something to tell you,” my wife says this morning, “and it’s going to make you sad. But I want to make sure I tell you before you hear it from somewhere else.”

“Okay.”

“David Bowie is dead.”

For a second, I sort of quit breathing. Whatever I’d imagined she was going to tell me, this was nowhere on the list. It feels impossible.

David Bowie is a peculiar icon, the sort that causes people to toss out important-sounding terms: savant, freak, chameleon, impostor, genius—the consummate performer of our time. While many pop stars understand that they have the ability to change clothes and become someone new, Bowie understood that all people spend their lives doing this. And so every couple of years he changed his costume, his face, his poetry, his sound, and he showed us the way. He showed us that we all had universes inside of us.

* * *

I cannot remember a time when I didn’t know David Bowie. My memories of watching Labyrinth on television at a tender age are so deep, it’s impossible to say when I first observed it. But it wasn’t until I was a teenager that I discovered his library of music. This might seem odd, since I come from a family of musicians—but my parents rarely pushed music on me (unless we were road tripping in the car and three-part harmonizing to The Beach Boys), and Bowie is not an artist who you truly learn from what they play on the radio. It took some time before I had my hands on copies of Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane, and what I learned from them blew the whole world wide open:

It’s okay to feel like an alien while you’re here.

As every good genre fan is wont to do, I went back into the lore, read every interview I could get my hands on and listened to every single album. I found thousands of photographs, hundreds of impossible jumpsuits and haircuts. And the strange part was—I loved all of it. (And I do mean all of it; the stadium crowd-pleasers, the experimental walls of sound, the industrial rock, the whole flipping discography.) I branched out to the friends and contemporaries—Marc Bolan, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, Brian Eno, so many more. I discovered glam rock, and found a strange pocket of music history that identified something about myself that had been far beyond my reach prior.

* * *

I press play on Ziggy Stardust as I step onto the subway platform today. It’s not even really my favorite Bowie album per se, but it seems the only place to begin mourning. As always, “Five Years” starts the journey:

I think I saw you in an ice cream parlour

Drinking milkshakes cold and long

Smiling and waving and looking so fine

Don’t think you knew you were in this song

I can feel the tears coming again, but I hold them back. The least I can do to honor David Bowie’s memory is keep the glitter and liquid eyeliner from running down my face. (Really, I should have gone for more glitter. If only it wasn’t so bitterly cold outside.)

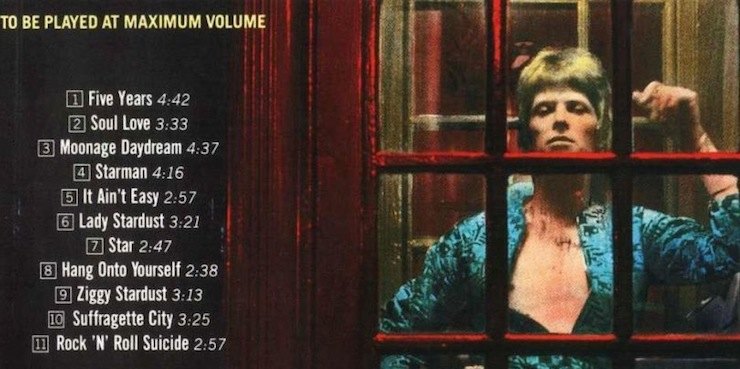

My headphones bleed a lot of sound, but I don’t bother to turn down my iPod out of courtesy, the way I normally would. The album always read “To Be Played At Maximum Volume” on the back cover, and that’s what I intend to do.

* * *

Holy shit, I thought as quietly as possible in the darkness of my room. I was seventeen, and guarding my thoughts had become its own pastime. I’m not straight, am I?

In going through the Bowie lexicon, I had discovered the interviews where he discussed being bisexual, and his attitude about the whole thing was decidedly cavalier. Later on in his career he rescinded most of those statements (though I can’t help but wonder if it was mostly because he got tired of people asking him whether or not he had sex with Mick Jagger). In the end, it doesn’t matter if he did it for the publicity, the shock value, or the freedom; David Bowie made bisexuality visible in a way that it had never been before.

We talk so much these days about how representation matters, and here’s some more anecdotal evidence to fuel the fire; I’m not sure I ever would have realized that I was queer if David Bowie didn’t exist. As a teen, I only knew that I wasn’t a lesbian, and that made things complicated. Most of the queer people I knew were simply gay, and the rest were “trying things out” which came with its own (typically insulting) labels from the adults around us. Gay-until-graduation, they’d say, or some other nonsense. Plenty of people don’t believe bisexuality exists at all (to say nothing of pansexuality), and I heard a lot of that too.

A friend and I had watched Velvet Goldmine in her basement one night during a sleepover. As young Arthur (played by Christian Bale) watched an interview where Brian Slade—a character heavily influenced by David Bowie during his Ziggy phase—commented on his own bisexuality, Arthur shouted “That’s me, dad! That’s me!” pointing to the screen as his father looked on in shame. Despite the clear disapproval, Arthur’s excitement was palpable; that clear point of human connection where you realize that you’re not alone, an anomaly, a broken piece of organic equipment.

And this boy had made that connection with a rock and roll god from another world.

* * *

Genre fans love David Bowie, and there are countless reasons why. For one, science fiction and fantasy were always staples of his work. References to space, aliens, dismal futures, super beings—they’re everywhere. He even tried to write a musical version of George Orwell’s 1984 (which later became the album Diamond Dogs). His music videos often feel like short form science fiction films all to themselves. He facilitated the sexual awakening of many young people in his turn as Jareth the Goblin King in Labyrinth. He stripped himself naked (literally) to play the alien Thomas Newton in The Man Who Fell to Earth. He was Catherine Deneuve’s vampire lover in The Hunger. He played Nikola-freaking-Tesla in The Prestige. Neil Gaiman admitted to basing his version of Lucifer off of the man, and that’s not the only place where his countenance pops up. Whenever someone is looking for a figure to indicate otherworldliness, he is usually top of the list.

It’s no surprise at all that the BBC series Life On Mars and its spin-off Ashes to Ashes used two key Bowie songs to form the lynchpin of their narratives. It’s also no surprise that those two shows are some of the best science fiction television ever produced.

Where Bowie was concerned, playing with genre, gender, pantomime and storytelling often went side by side by side, which made him a particular harbor for the world’s outcasts and oddities, the kids looking for permission to express their weirdest heart’s desire. His music has always been popular, of course, but there was a hidden world out there for people who wanted more than an “Under Pressure” singalong at the karaoke bar. When you continued to dive, you came across smears of lipstick and deconstructed personal mythology, fashion and architecture, philosophy and camp living happily together, all of it superbly orchestrated into a kind of unified poetry.

David Bowie was his own space opera fantasy epic, responsible for bringing up generation after generation of strange star children.

* * *

I have a Bowie tattoo with lyrics from his 2003 album Reality. It’s from the title track, and it reads: “Never look over reality’s shoulder.” I had it positioned so that it starts on my back and curves up. Which means that my shoulder… says “shoulder.”

I often use this as an abstract compatibility test. If someone indicates that they believe this placement was a mistake, I know we won’t be very good friends.

* * *

There are David Bowie songs that suit my every mood, that speak to every emotion I’ve ever experienced. There is never a time when he’s not needed, omnipresent. Conversely, there are Bowie songs that speak to emotions I’ve never known, moments I’ve not lived. It’s comforting at once to know that I have more to learn, that I’m not through being human just yet.

* * *

Sometimes, like a gift of second sight, you can sense what’s on the horizon.

It’s not really being psychic or anything—it’s a series of impressions, your brain calling up patterns and imagery, identifying the signs, giving you this sense of wrongness.

I didn’t buy the latest (last) Bowie album, Blackstar, when it was released a few days ago. There was something about it, about the timing and the look of the thing, that was making me nervous. I thought I’d wait it out for a few weeks, then buy the album when all the hubbub had died down. For some reason, all I could think was I’m not ready.

I’m not ready.

Sometimes, your subconscious just connects the dots and understands what’s coming.

* * *

The best thing about grieving en masse on the internet is how personal it is.

That sounds like an oxymoron, I’m sure, but my Facebook and Twitter feeds are currently full of songs and images. And the selection, the curation of the media tells me something about every person who feels the need to speak up. What incarnation, song, lyric they love most, or what feels the most appropriate. What memories they tie to this man, what he meant to them. I hated having to pick one image. I could never pick a single song.

But I suppose Bowie already knew it best, how to say goodbye—he’s died before, after all. Well, Ziggy has, at least.

Just turn on with me and you’re not alone

Let’s turn on and be not alone

Gimme your hands ’cause you’re wonderful

Our Starman came to meet us, blew our minds. But then he had to leave, because that’s what messiahs do. In some ways, he’s been preparing us for this from the start, which makes it all the more poignant. I only hope that when we dance, when we ponder, when we love, we’re doing him proud.

Gimme your hands… ’cause you’re wonderful.

Emmet Asher-Perrin is probably going to go home and watch the Hammersmith Odeon concert on DVD, and sob into some sparkling rosé. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.