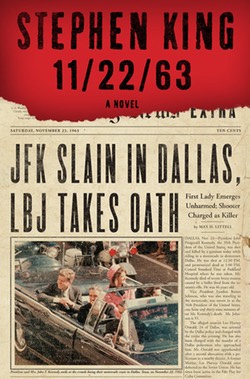

In 1971, eight years after the JFK assassination, Stephen King started writing a book called Split Track. Recently hired as an English teacher at Hampden Academy, he had just published a short story called “I Am the Doorway”, almost sold a novel called Getting It On to Bill Thompson at Doubleday, and he was constantly sucking up ideas. As he recalls, “It was 1971 and I was in the teachers’ room and people were talking about the Kennedy assassination. The 22nd would roll around and people would talk and write about the assassination and stuff. I guess somebody must have said, ‘What would it have been like if Kennedy had lived?’ And I thought to myself, ‘I’d love to write a story about that.’ ”

Newly married, with a one-and-a-half year old daughter at home, barely three months into his first teaching job, he was overwhelmed by the amount of research involved and gave up after writing 14 single-spaced pages. 36 years later, in the January, 27 issue of Marvel Spotlight, King wrote about a comic he was considering that told the story of a guy who travels through a time portal in the back of a diner to stop the Kennedy assassination, but changing history turns the present day into a radioactive wasteland and he has to go back again and stop himself from stopping Oswald. King thought this story might reach “an audience who’s not my ordinary audience. Instead of people who read horror stories, people who read The Help or People of the Book might like this book.” Six months later, King’s researcher, Russell Dorr, went to work on the Kennedy assassination in preparation for King’s next book. And, in January, 2009, 38 years after first getting the idea, King began typing the beginning of what would become 11/22/63. And he was right. It would turn out to be his biggest bestseller in over a decade.

Because every writer has to come up with their own theory of how it works, books about time travel quickly become more about the travel and less about the times they travel to. Grandfather Paradoxes (“What if I kill my own granddad?”), branching timelines, and the butterfly effect are so juicy they quickly overwhelm any time travel narrative until the manuscript becomes mostly about the mechanics. Not for King. His rules of time travel are pretty simple:

- You enter through a portal in the back of Al’s Diner.

- No one knows how the portal works or why.

- You always show up on September 9, 1958.

- No matter how long you stay in the past, only two minutes pass in the present.

- The past can be changed, but each trip through the portal resets the time line.

- History resists attempts to change it.

As for the Grandfather Paradox, when main character, Jake Epping, asks what would happen if he killed his grandfather, Al replies, “Why on earth would you do that?” The mechanics are dispensed with fast and breezy because what King wants to write about is the time to which Jake travels, 1958, when root beer cost 10 cents and tasted better, when fast food didn’t exist, and when chocolate cake tasted like real chocolate. King was 11 years old back then and the 1958 he writes about — with its vividly evoked music, its pungent smells, and its powerful tastes — feels less like the past and more like a memory, where even the most mundane details stand out in sharp, glittering relief. This is Steven Spielberg’s past, all golden beams of sunlight and small town Americana. But right from the start, King’s vision of the Fifties has a touch of decay around the edges. The past may be great, but its mask is slipping.

As for the Grandfather Paradox, when main character, Jake Epping, asks what would happen if he killed his grandfather, Al replies, “Why on earth would you do that?” The mechanics are dispensed with fast and breezy because what King wants to write about is the time to which Jake travels, 1958, when root beer cost 10 cents and tasted better, when fast food didn’t exist, and when chocolate cake tasted like real chocolate. King was 11 years old back then and the 1958 he writes about — with its vividly evoked music, its pungent smells, and its powerful tastes — feels less like the past and more like a memory, where even the most mundane details stand out in sharp, glittering relief. This is Steven Spielberg’s past, all golden beams of sunlight and small town Americana. But right from the start, King’s vision of the Fifties has a touch of decay around the edges. The past may be great, but its mask is slipping.

Al, proprietor of Al’s Diner, used the portal for years to do nothing more ambitious than buy discount beef in the Fifties, but one day the idea of preventing JFK’s assassination popped into his head and it wouldn’t leave. The only problem was that he had to live in the past for the five years from September 9, 1958 to November 22, 1963 and cancer cut his trip short. King’s been cutting a lot of lives short with cancer recently, and 11/22/63 features not one but two people who die of the Big C. Before he croaks, Al passes his mission to Jake, an English teacher (same as King was when he started this book), and Jake takes it on, deciding to try to save the life of someone he knows first to see if the change will take and what the consequences will be. To do that, Jake travels back to Derry, ME, setting for King’s It, and the first third of this book feels like a graceful, quiet coda to that book. I’m not a big fan of King’s attempts to build an interlocking fictional universe, but when Jake approached Derry I got a genuine thrill, and his first mention that “there was something wrong with that town” electrified my spine.

After his trial run goes off successfully, Jake goes back to the past for real and confronts his biggest challenge: he needs to find a way to kill five years without killing himself, while navigating the slang, coins, and social mores of the era, as well as dealing with accidentally bringing through his cell phone. This minutiae is more fascinating than I imagined it would be, and Jake’s immersion in the past becomes the subject of the novel. One of those guys who’s constantly on the outside of the party looking in through the window, this book is less about the Kennedy assassination and more about how Jake finally decides to go inside and join the fun. He stops off in Florida briefly, as almost every recent King book seems to require, then moves to Texas where he decides that Dallas is too toxic for him, portraying it as a sort of Southern doppelganger to Derry. He settles on nearby Jodie, TX instead. “In Derry I was an outsider,” he writes. “But Jodie was home.”

After his trial run goes off successfully, Jake goes back to the past for real and confronts his biggest challenge: he needs to find a way to kill five years without killing himself, while navigating the slang, coins, and social mores of the era, as well as dealing with accidentally bringing through his cell phone. This minutiae is more fascinating than I imagined it would be, and Jake’s immersion in the past becomes the subject of the novel. One of those guys who’s constantly on the outside of the party looking in through the window, this book is less about the Kennedy assassination and more about how Jake finally decides to go inside and join the fun. He stops off in Florida briefly, as almost every recent King book seems to require, then moves to Texas where he decides that Dallas is too toxic for him, portraying it as a sort of Southern doppelganger to Derry. He settles on nearby Jodie, TX instead. “In Derry I was an outsider,” he writes. “But Jodie was home.”

It’s also where he falls in love with Sadie, a tall, clumsy, passionate (and, in an unrealistic twist, virginal) librarian. And that love becomes the real core of the book. King goes deep on Jake’s life in Jodie and especially his life as a small town schoolteacher, directing the drama club’s Of Mice and Men production, talking his students through their dark nights of the teenaged soul, organizing fundraisers when they get hurt, chaperoning dances. This is King’s most sustained and detailed look at the life of a high school teacher since The Shining and it serves as a love letter to the road not taken in King’s life (if he’d never sold Carrie would he still be happy?), as well as the road not taken for America (if Kennedy hadn’t been shot would everything be better?). The answer to the first of those questions is a resounding “yes.”

Jake gets bored of waiting for 1963, at one point shouting at himself, “What are you doing fooling around?” prompting the reader to say, “I’ve been thinking the same thing for the past 100 pages.” But it’s hard to write about being bored without being boring, and fortunately the cold touch of terror begins to make itself known. There are precognitive dreams that bring evil omens, bits of coincidence and repeated language that hint reality is starting to fray around the edges, and we get glimpses of both the misogyny, racism, and general addiction to cancer sticks that also characterized the late Fifties and early Sixties. In addition, to stop Oswald, Jake has to make sure Oswald actually is the lone gunman and not part of a larger conspiracy, which forces him to move into Oswald’s squalid, depressing life, spying on him until he’s sure that he is — as King said in an interview — nothing more than “a dangerous little fame junkie.” (King believes with 99% certainty that Oswald acted alone. His wife, Tabitha King, disagrees and thinks there was a conspiracy.)

Jake gets bored of waiting for 1963, at one point shouting at himself, “What are you doing fooling around?” prompting the reader to say, “I’ve been thinking the same thing for the past 100 pages.” But it’s hard to write about being bored without being boring, and fortunately the cold touch of terror begins to make itself known. There are precognitive dreams that bring evil omens, bits of coincidence and repeated language that hint reality is starting to fray around the edges, and we get glimpses of both the misogyny, racism, and general addiction to cancer sticks that also characterized the late Fifties and early Sixties. In addition, to stop Oswald, Jake has to make sure Oswald actually is the lone gunman and not part of a larger conspiracy, which forces him to move into Oswald’s squalid, depressing life, spying on him until he’s sure that he is — as King said in an interview — nothing more than “a dangerous little fame junkie.” (King believes with 99% certainty that Oswald acted alone. His wife, Tabitha King, disagrees and thinks there was a conspiracy.)

This is an old man’s book, the way It was a middle-aged man’s book, and The Stand was a young man’s book, and like those, you feel that King has reached a moment when he’s looking back over how far he’s come and delivering a summation of all that he’s learned. He’s perfected his talent for realistic writing about everyday life since It, in books like Misery, Dolores Claiborne, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, and so many short stories. He’s able to give humdrum reality a burnished gleam, making its moments glow the way they do in an old man’s memory because they’ve been taken out and polished so many times. His depiction of the way Derry’s and Dallas’s dark underbellies keep bleeding over into the daylight world is much more balanced and accomplished than it was even in It, achieving the kind of “worm beneath the skin” darkness that David Lynch conjured up in Blue Velvet, and that kind of control probably wouldn’t be possible if he hadn’t done a similar thing in the story “Low Men in Yellow Coats” in Hearts in Atlantis.

The sheer size of 11/22/63 makes it easy to forgive a lot. In an 849 page book, 40 boring pages are a rounding error. And while there are many maudlin moments—kissing away a dying man’s last teardrop, helping a simple-minded, good-hearted janitor get his high school diploma, and the fact that the entire book is predicated on that hoariest of cliches, a young man’s oath to honor a dying friend’s last request—they are dwarfed into insignificance by the sheer scope of the book. 11/22/63 is like a massive, slow-moving cruise liner. It takes forever to turn, but when it does the motion is magnificent.

The sheer size of 11/22/63 makes it easy to forgive a lot. In an 849 page book, 40 boring pages are a rounding error. And while there are many maudlin moments—kissing away a dying man’s last teardrop, helping a simple-minded, good-hearted janitor get his high school diploma, and the fact that the entire book is predicated on that hoariest of cliches, a young man’s oath to honor a dying friend’s last request—they are dwarfed into insignificance by the sheer scope of the book. 11/22/63 is like a massive, slow-moving cruise liner. It takes forever to turn, but when it does the motion is magnificent.

It’s also an old man’s book in the way it echoes The Dead Zone. King was a 32-year-old author when he wrote that book, about a school teacher trying to assassinate a presidential candidate because he had a vision the man was insane and would start a nuclear war that destroyed the world at some indeterminate future date. When he wrote 11/22/63 King was 63, writing about a school teacher going back to the past because he found he was living in a fallen future, where America had lost its way and destroyed the best parts of itself. Like Hearts in Atlantis, it’s another book from King reckoning with the betrayed promise of the Sixties. In The Dead Zone, the school teacher, Johnny Smith, changes the future by almost killing the presidential candidate, and thus he saves the world. In 11/22/63, Jake learns that the cure is worse than the cancer, and it’s better to leave the future alone. Enjoy the past for what it is, the books says, don’t turn it into a tool to fix future problems. The original manuscript of the book ended on a melancholy note, with Jake sacrificing his relationship with Sadie to undo the damage he’s done. But Joe Hill, King’s son, told him there had to be a more optimistic ending, and King listened. As it stands, the ending is predictable and corny, but if you’re anything like me you’ll pretty much cry through the entire last chapter. And that’s another way it’s an old man’s book. Sometimes you need to live a full life to realize that happy endings aren’t a sign of weakness. Sometimes, in this crazy, hurtful world, they’re acts of mercy.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today. He is the author of Horrorstör, the only novel about a haunted Scandinavian furniture store you’ll ever need, and My Best Friend’s Exorcism, which is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist. His next book is a non-fiction chronicle of the boom in horror paperback publishing in the Seventies and Eighties that followed in the wake of Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and Thomas Tryon’s The Other. It’s called Paperbacks from Hell and will hit shelves in September 19th.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today. He is the author of Horrorstör, the only novel about a haunted Scandinavian furniture store you’ll ever need, and My Best Friend’s Exorcism, which is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist. His next book is a non-fiction chronicle of the boom in horror paperback publishing in the Seventies and Eighties that followed in the wake of Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and Thomas Tryon’s The Other. It’s called Paperbacks from Hell and will hit shelves in September 19th.