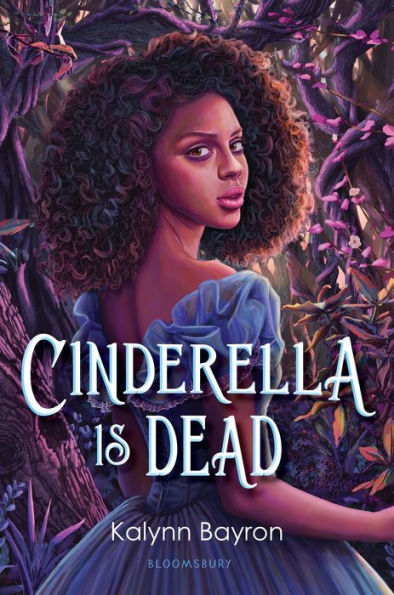

In 2018 I was in the depths of submission hell. I had this novel about queer Black girls living in the former kingdom of Cinderella 200 years after the fabled princess’s death. It centered Black girls in a fantasy setting and was full of magic, adventure, peril, levity, and sisterhood. I’d been working on it for about two years and after finding an agent, we went on submission.

One of the first things people tell you when you get into publishing is that the industry is highly subjective and that you shouldn’t take the rejections you will ultimately receive when querying, or when you’re on submission, personally. From what I’ve seen I’d say half of the time, that’s true. There are myriad reasons a story may not be the right fit for an agent or editor and those passes don’t sting quite as much. But there is no denying that in publishing, as there is in every other system built on a foundation that has specifically excluded marginalized creators, there is an element of selectivity, of bias—insidiously polite terms for racism and homophobia masquerading as “quality control”. Because I share my main character Sophia’s intersectional identity as a Black queer woman, and because it was very clear that in some cases that was the reason we didn’t get a bite, it was personal at least some of the time. It’s exhausting to constantly be wondering if the most recent pass was because of something I could improve upon or if it was because of something that I can’t—and wouldn’t—change about who I am as a person.

One of the most common reasons I received a pass on this manuscript was that the market was oversaturated with retellings, that they had been done to death. Cinderella Is Dead is not a retelling as much as it is a remix. It’s not a story that hits the familiar beats of orphaned girl is mistreated by step-family, saved by Prince Charming, lives happily ever after. This book is not that. I felt like I was missing something. If a story like the one I’d written was so overdone, why didn’t I see it? Where in the bookstore or the library are the YA fantasies where all the main characters are queer Black women? Where are the YA fantasies where Black women are being desired, fought for, and allowed to have adventures without having to act as props for white main characters who don’t understand that racism is bad until their Black friend is violently mistreated?

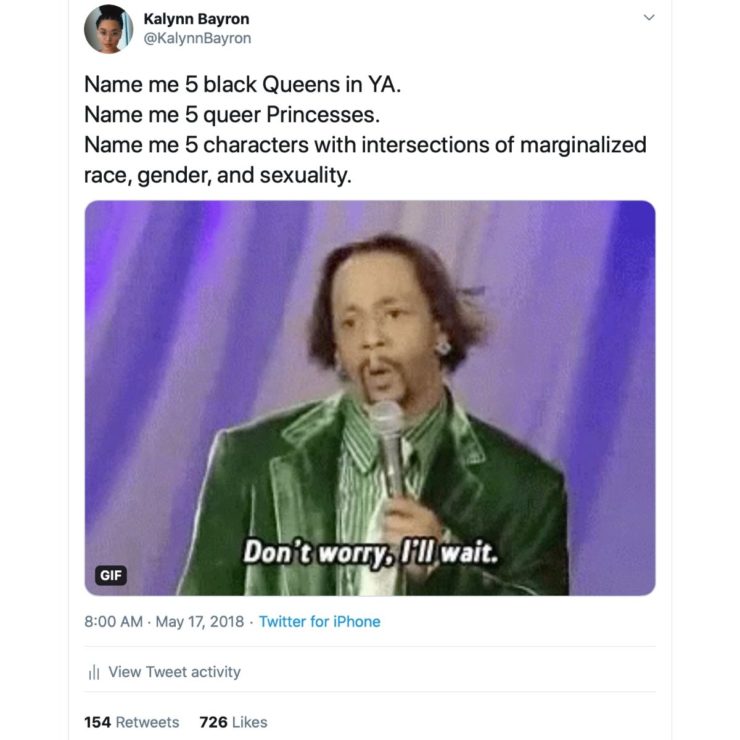

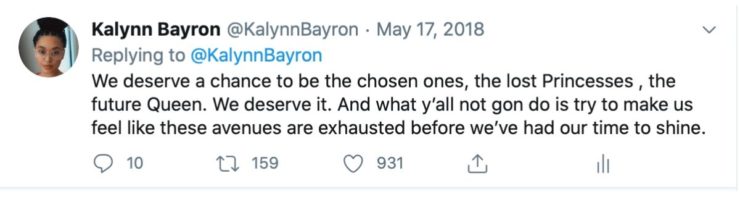

I had some thoughts. So, I did what any self-respecting millennial would do–I tweeted about my frustrations and used appropriate GIFs to express my feelings. Sometimes yelling into the void is cathartic, especially when you have a relatively small following and just want to get something off your chest. However, sometimes the void answers back and you question your choices.

Other tweets in the thread didn’t do huge numbers but were still enough to make my phone malfunction.

The numbers weren’t astronomical. They were more like viral-lite or diet-viral. But what this tweet did was open up yet another discussion about inclusivity and intersectional identities within the publishing industry—a discussion we are forced to keep having because publishing’s reputation for moving at a glacial pace apparently also extends to its ability to diversify its workforce and this in turn causes another roadblock for BIPOC, and queer BIPOC in a journey that is stacked against us from the jump.

Buy the Book

Cinderella Is Dead

In the past two years—a time period wherein lots of folks think we’ve made leaps and bounds in the makeup of the publishing industry (spoiler: we have not)—we are still being told that our stories don’t matter, that white straight cis people not being able to connect to a story about Queer Black people is a legitimate justification for a pass, that big houses already have their one Black girl book this season, that being Black AND queer AND a woman is just too much.

Stating publicly that a specific plot device is overdone, that you’re tired of seeing Queens, Princesses, Royalty, and chosen ones is a really great way to show marginalized creators who really counts in this industry. Underrepresented authors who write underrepresented characters have not had nearly enough time to shine. We have barely begun to see ourselves reflected in fantasy and now you’re over it? Not back when it was fifty-leven white authors were doing it?

Below is just one of the many responses I got to that thread that perfectly illustrate the kind of cognitive dissonance at work here. In an industry that is 76% white there are still folks screaming, “What about the white kids?”. Listen, the white kids are all right. I promise you they are. They have the rep they need and want and they’re getting more and more of it every publishing season.

I sometimes use the analogy that goes if we aren’t given a seat at the table, we’ll build our own. I think this way of thinking comes from a level of resiliency that many Black women, and Black people in general, are expected to possess. We so often take things into our own hands because we are denied equal access, equal rights, equal treatment, but the analogy is inherently flawed. It does a disservice to those who have come before, who have built tables only to have them burned to ground by gatekeepers who cannot fathom that stories that don’t center the white, cis, heteronormative gaze could ever be worthy of inclusion. We don’t need to build a new table, we want the arsonists who continue to destroy the ones we’ve built held accountable.

We are seeing more and more Black girls in ball gowns on the covers of YA fantasies. We are getting more main characters who are BIPOC, done in a way that feels authentic and meaningful. Most importantly, we are getting these stories from writers who share some or all of these character’s underrepresented identities. My editor used this Tweet when she took Cinderella Is Dead to acquisitions to show that people were not, in fact, over these popular themes. This novel found a home but not before implicit and explicit racial bias came into play, not before people asked me to try making my main character “a normal” girl, and not before I was asked to consider writing a story that straight white kids could better relate to.

Our stories, our reimaginings, our retellings, are worth sharing, worth shouting about and should be allowed to take up space. Nothing is over and done, not until we get a turn.

[Author’s note: The original Tweet in this thread was taken down without reason or notice by Twitter. The above image is a screenshot I took a while back.]

Kalynn Bayron is an author and classically trained vocalist. She grew up in Anchorage, Alaska. When she’s not writing you can find her listening to Ella Fitzgerald on loop, attending the theater, watching scary movies, and spending time with her kids. She currently lives in San Antonio, Texas with her family.