Every year, people who get paid to write on the internet celebrate a very strange ritual: we try to dig up obscure Christmas specials, or find new angles on popular ones. Thus, we receive epic takedowns of Love Actually; assertions that not only is Die Hard a Christmas movie, it’s the best Christmas movie; and the annual realization that Alf’s Special Christmas is an atrocity. These are all worthy specials, deserving of your limited holiday media time. However, I have not come here to ask you to reconsider anything, or to tell you that something you watch each December 24th is actually garbage—I am here to offer you a gift.

The gift of AD/BC: A Rock Opera.

Created in 2004 by the same people who made Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace, The IT Crowd, and The Mighty Boosh, AD/BC: A Rock Opera is a (literally) note-perfect parody of ’70s religious musicals, wrapped in a mockumentary about the making of the musical itself. AD/BC tells the story of the Innkeeper who denied Joseph, Mary, and the not-quite-born Jesus a room in his inn. And more importantly, it features lyrics including: “Being an innkeeper’s wife, it cuts like a knife”; “You call the shots, You made the world, so fair enough, Lord”; and “as the Good Book says, a fella’s gotta keep his chin up when he gets uptight!”—all sung in perfect ‘70s rock style. Because life is meaningless and unfair, Richard Ayoade and Matt Berry only got to make one of these specials, it was only shown once on BBC3, it wasn’t released on DVD for another three years, and it never became a perennial like other, lesser specials.

A taste:

As in Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace (which I’ve written about before), part of the fun is in watching the writers and actors play with the show’s layering—actors portraying actors, acting. Real world actor Julian Barratt is “Roger Kingsman” of The Purple Explosion, who plays Tony Iscariot in the musical; Julia Davis plays “Maria Preston-Bush”—described only as “beautiful”—who portrays Ruth, the Innkeeper’s Wife; Richard Ayoade is “C.C. Hommerton,” a dancer cast as Joseph despite the fact that he can’t sing; and Matt Lucas is “Kaplan Jones,” a professional wrestler who provides the voice for an overdubbed God. The role of the Innkeeper is brought to life by Matt Berry as the musical’s writer-director “Tim Wynde,” who is exactly the sort of velvet-frockcoated, prog-rock nightmare that this decade produced. You can learn more about Tim Wynde’s lyrics, his affair with Preston-Bush, and his falling out with Homerton in the DVD extras if you want, but unlike in Darkplace, where the layers each add more nuance to the comedy, it isn’t strictly necessary here. The only thing that will help you here is an understanding of the intersection of religious spectacle and musical theater.

You see, AD/BC isn’t an ’80s pastiche like Darkplace, or an office comedy like IT Crowd, or a surrealist manifesto like The Mighty Boosh—it’s a hyper-specific parody of Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar. And because nothing is more useful than a person excitedly explaining why something is funny, I’m going to tease out the particular matrix of references that make AD/BC a worthy addition to your holiday media canon.

Pretty much as soon as film started, people started using it to tell stories from the Hebrew Bible and New Testament. The Hebrew Bible offers thousands of stories of heroic men and seductive women, hot people doing naughty things and then feeling very bad about it—stories that, thanks to the source material and pseudo-historical settings, could skirt the Hays code and draw the likes of top actors Gregory Peck, Susan Hayward, Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner, Joan Collins, and Gina Lollobrigida. Hollywood producers figured this out, and gave us Samson and Delilah (1949), The Ten Commandments (1956), Solomon and Sheba (1959), The Story of Ruth (1960), David and Goliath (1960), Esther and the King (1960), Sodom and Gomorrah (1962), and The Bible: In the Beginning… (1966), along with others I’ve probably missed. It was a formula that worked well (and provided early TV with reliable Easter/Passover programming too!) because the Hebrew Bible is just dripping with stories of adultery, murder, repentance, heroic sacrifice—it is religion tailor made for Technicolor Cinemascope.

Then you get to the New Testament, which doesn’t lend itself nearly as well to epic film making. Huge swaths of it are just people talking to each other about boring concepts like compassion and empathy. Instead of a bunch of fascinating characters—Moses, David, Solomon, Judith, and Ruth—you just get one guy, Jesus, and he dies partway through, but everyone just keeps talking about him because no one else is as interesting. There’s another problem that you only really get with the New Testament: since the canon was cobbled together from many different gospels with wildly different takes on Jesus’ life and teachings, you have to make a decision when you start work on your New Testament adaptation: do you pick one Gospel and stick with it exclusively? Do you try to merge four different books together in a way that makes sense? Or do you try to tell the story in a way that doesn’t really focus on Jesus so much?

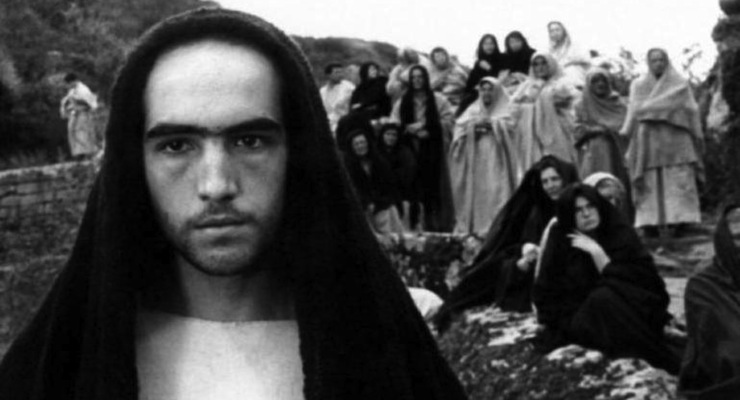

Pasolini’s Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) takes the first approach, by literally transcribing the text and action of Matthew into a black-and-white film featuring non-professional actors. The two great attempts at making Biblical epics about Jesus—King of Kings (1961) and The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)—both tried the syncretic method, mashing all four gospels together to tell a cohesive story. Both films are long, and a bit overstuffed, with Greatest Story in particular cramming in cameos from people like John “The Centurion” Wayne and Pat “The Angel at the Tomb” Boone. Most studios preferred to take the third route, using side characters to tell the story rather than Jesus himself. So in The Robe (1953), for instance, we learn about how Jesus’ robe impacted the lives of a few Romans. Its sequel, Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954), follows the travails of a Christian gladiator, and in the earlier Quo Vadis (1951) we check in with Peter and a group of early Christians during the reign of Nero. Where the two big-budget Jesus epics sputtered at the box office, these films were hugely popular, probably because they were bound by a sense of reverence. Quo Vadis can announce a belief in Jesus’ perfection, and then leave that off to the side while the audience focuses on the more cinematic story of humans screwing up.

Overtly religious movies mostly fell out of favor by the end of the 1960s. BUT! There were two big exceptions, and they managed to become instant time capsules of a very weird era, while also creating the kind of cheeseball cinema that inspired AD/BC. Godspell (1973) and Jesus Christ Superstar (1973) both tackle the Jesus story head-on, focusing on the last few days of his life, including large blocks of parable and New Testament quotes, but they did it in song. Both films attempt to modernize their stories to hilarious effect. The film adaptation of Godspell does this by setting the action in New York City, where Jesus and his disciples can run around Central Park, dance on the not-yet-complete World Trade Center roof, and hold the Last Supper in an abandoned lot. This, in addition to the folk-pop and the hippie garb, does a pretty good job of screaming “The filmmakers would like you to know that this story is relevant to your life, young person!” in a way that I personally find endearing. Jesus Christ Superstar takes a slightly different route by taking a more worldly approach to their story. Judas (pretty much Jesus’ second-in-command in this version) is a freedom fighter, and many of the disciples want to take up arms against the Romans—Jesus is the only one who’s taking a spiritual view on his mission. Finally, the film goes out of its way to use wacky camera tricks, sets that are obviously sets, and, in a move that’s either brilliant or unforgivably hokey, the entire cast arrives in a ramshackle bus to start the film, and everyone (except Jesus) leaves again at the end, underlining the idea that this is a group of people putting on a show.

Godspell favors folk pop and elaborate dance routines, and their Jesus (Victor Garber) looks like this:

Jesus Christ Superstar went full rock opera, and their Jesus (Ted Neeley) looks like this:

And now, straight from AD/BC, here is Matt Berry’s Innkeeper:

Look at that blue gel! Stand in awe of those flowing locks! But here’s the important bit: does AD/BC coast on being silly? Does it stop with some ridiculous camera tricks and call it a wrap? Nay, not so, gentle readers. It takes all of the above-mentioned religious-movie-history into account, and applies it to a 28-minute long comedy special. It uses the old epics’ trick of focusing on a side story, and chooses to humanize the Innkeeper, who ranks somewhere beneath The Little Drummer Boy in the Nativity’s order of importance. Ayoade and Berry steal Norman Jewison’s camerawork, and clutter their set with light rigs and “mountains” that are clearly crates with blankets thrown over them, thus invoking Jesus Christ Superstar. They take Godspell’s pop-fashion sense and dress background characters in absurdist swimming caps. They genderswap their casting of The Three Wise Men!

That’s all before I even talk about Ruth, the Innkeeper’s Wife (her life cuts like a knife, if you recall) who is a dead ringer for Frieda in A Charlie Brown Christmas. That’s before I get into the specific musical cues, or the way the sets sway when people bump into them, or the fact that Bethlehem’s citizens include both a cab driver and a full time restaurant critic. That’s before we talk about Judas’ dad, Tony Iscariot, who has learned the ways of love from men of the Orient. Or the way Tony and the Innkeeper each get to sing “GET OOOUUUT!!!” just like Ted Neeley does in Jesus Christ Superstar!

Really, I could talk about AD/BC all day, but instead of that, I’ll simply urge you to share the gift of “The Greatest Story Never Told” with your family and friends this holiday season.

Originally published December 2015.