It’s a bit strange, I think, how little writing advice is about feelings. There is abundant writing advice about everything else—from saving the cat to killing our darlings, to never/always using “said,” writing what we know, info-dumping and more—but not a whole lot specifically focused on the fundamental question that faces every writer when we sit down to write: How do we make people care?

Because it doesn’t happen automatically. It doesn’t appear naturally just because you get all the other elements right. We know that approach doesn’t work, because we’ve all read and watched things that seem complete and polished and skillful, but still leave us feeling absolutely nothing.

On the other hand, we’ve also all read and watched fiction that isn’t polished or perfect, but still manages to punch us right in the feelings. We all know stories that make it so very easy to list their abundant flaws or shortcomings, but still leave us with the impression that none of that matters, because wasn’t the experience brilliant anyway? I want to spend some time thinking about how to do that, because it comes from specific choices in the storytelling. Choices that are, I think, very much worth our attention.

Being a professional author as well as a former scientist, I have chosen to approach this problem in the most rational and scholarly manner possible, which is why I have watched a shit-ton of gay fantasy Chinese television drama and will now tell you all about it.

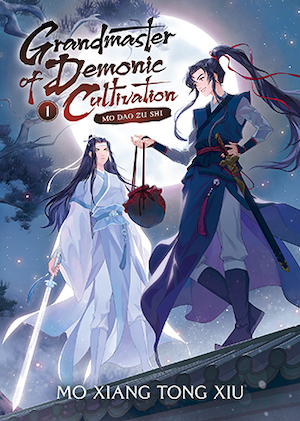

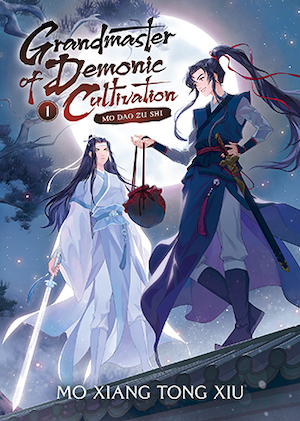

So let’s talk about Mo Dao Zu Shi, or The Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation. It’s a Chinese novel by author Mo Xiang Tong Xiu , first published on Jinjiang Literature City in 2015-2016. Although there have been fan translations floating around the internet for years, the first volume of the official English translation was just published by Seven Seas in December. As a result, many non-Chinese fans (including me) got to know the story primarily through its adaptations: the donghua of the same name (on YouTube, with the title translated as The Founder of Diabolism) and the live action show The Untamed (on Netflix and YouTube; the Chinese title is Chen Qing Ling). There is also a manhua, a chibi series, more than one audio drama, fan translations in at least six languages, and so much more. Although its popularity exists largely outside of English-language pop culture, MDZS (as it is called) is widely popular on a scale that most stories will never approach.

Buy the Book

Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation: Mo Dao Zu Shi (Novel) Vol. 1

Mo Dao Zu Shi is a danmei (gay romance) xianxia (like wuxia with more fantasy) novel that takes place in some undefined magical era of Chinese history. It’s about a feared and reviled necromancer who is brought back to life several years after his horrific death, and gets pulled into sorting out a mystery with the help of his powerful and respected mutual crush, the one person who stood by him even when the whole world was against him. Along the way we learn the whole troubling tale of how a brilliant young man can go from being a carefree teenager to a war hero to public enemy #1, with every facet of the story a pointed lesson in how very fraught concepts like right and wrong, good and evil, loyalty and betrayal, perception and truth can be. It’s romantic! It’s dramatic! It’s gory! It’s full of trauma and angst! There are emotional support bunnies! There is war and political scheming and murder! Families are formed and torn asunder! There are swordfights and battles and entire armies of zombies!

This is big, dark, layered epic fantasy, adapted in slightly different ways for different media. Is it perfect? Not even close. Is it problematic? Certainly. Is it full of troubled people doing terrible things? Full to the brim. Are all of the characters and their relationships wildly dysfunctional? Damn right. Does it feel like parts of its 1500 or so pages were written in a giddy fever dream? Sure does. Does the censorship of queer, supernatural, and so-called “immoral” content in Chinese media force the adaptations into some head-scratchingly bizarre choices? Absolutely. Do fans have raging internet battles over those changes and various degrees of character villainy and the proper translations of sex scenes? All the time, my friends. All the time.

Does any of that matter? Not in the slightest.

If we want to learn how to create stories that punch people in the feelings, stories that make people care, the best place to learn is from a story that does exactly that, repeatedly, in a gleefully abundant manner, without the least hint of restraint or embarrassment.

This is what I have learned:

Ignore the Haters and Start Your Story However You Want

Everybody hates fantasy prologues! Editors hate them, agents hate them, readers hate them! Prologues stole their girlfriends and shoved them into a locker! This is what you learn when you look for advice about fantasy story structure.

To which I say, with utmost maturity and professionalism: ugh, who cares. You can start your story however you want, as long as it is a beginning that achieves what you want it to achieve.

MDZS begins with the death of its main character—”Great news! Wei Wuxian is dead!”—then immediately skips forward to his resurrection several years later. Between the prologue and the first few chapters, what we learn is that this supposedly very bad Wei Wuxian fellow killed a shit-ton of people, then died, and now he’s back, and in quick succession he runs into his adolescent crush/frenemy, his orphaned nephew, his estranged brother who killed him, and the reanimated corpse of an old friend. It’s like a firehose of information with no context. Context is for fools.

This is a fairly bonkers way to start a story! Note the absence of any traditional beginning elements, such as the establishment of a status quo prior to being disrupted. But this beginning is accomplishing several things at once. It’s sparking our natural fascination with tragedy and its aftermath: we want to know what could lead to such a gruesome end, as well as why it wasn’t the end after all. It’s hinting at a sense of injustice: we immediately suspect there is more to the story than what the people in-universe believe. It’s suggesting a complex web of relationships with the briefest character introductions.

These are all seeds of emotional engagement. None of this is big emotion, not yet, but it doesn’t have to be. We can’t expect the audience to care wholly before they know what they’re caring about. That comes later. For now, we start with teasing hints—several of them, for different facets of the story—to draw people in.

Weaponize Your Audience’s Expectations Against Them

Another thing about this beginning: it’s playing with us.

The prologue tells us outright about the big mid-story climax that everything else is built around: a young man has become so very evil with dark power that a whole alliance of people, led by his own brother, has to band together to kill him!

What follows immediately flips that set-up on its head by introducing us to Wei Wuxian when he comes back from the dead, and he’s not what we would expect of a reviled and feared evil necromancer. He’s cheerful, friendly. Kind to children. Immensely likeable. Not remotely broody. He seems to hold no grudges for having been outcast and hated and dying so horribly. He certainly isn’t looking for revenge; he mostly looks back at his grim past and thinks, “Wow, I sure made some choices.” He didn’t even ask to come back from the dead; that happens because of somebody else. He frequently argues with a donkey and loses.

So now we are not just wondering how the events of the prologue could come about, but how it could happen to this character in particular. Our suspicion that there is more to the story is immediately confirmed, while at the same time our initial guesses at the nature of the character relationships go through some rather severe adjustments. Knowing not just what happened, but who it happened to, effectively establishes that the events as reported in the prologue are a funhouse mirror distortion of the true story that’s about to unfold.

You’re Building a World Whether You Want To or Not, So Do It on Purpose

I am not Chinese. I don’t read or speak Chinese. I did not go into MDZS familiar with either danmei or xianxia tropes, nor with the larger cultural context of wuxia-inspired stories. I’m slightly more knowledgeable now, but when I first jumped in, I noticed right away that a lot that is never explained for an unfamiliar audience.

Which is, to be clear, perfectly fine. More than fine: it’s great! I like that in a story. What is the point of fiction if not to introduce new worlds and new perspectives into our heads?

In this case, I’m not talking about only the fantasy things being unfamiliar, like why they fly on their swords or how curses or talismans work. I’m talking about big, foundational things concerning the nature of the world, such as how death and reincarnation are viewed, how society is structured, what familial obligations a person has, what makes a strong leader, what is considered orthodox and what is anathema, what it means to be a good person.

All of which matters intensely in MDZS, which is a story about a person who does forbidden magic for reasons related to a complicated knot of loyalty and obligation. To know what it means to raise the dead, we have to know what it means to be dead. To know what it means to act against what is considered decent and upright, we have to know how morality is defined. To know what it means to be a war hero or a war criminal, we have to know what is considered acceptable in war. All of those things are worldbuilding.

Just like with prologues, it has become somewhat fashionable of late to vocally hate worldbuilding. I’m not interested in rehashing that debate, so instead I shall gently point out that every story contains worldbuilding, whether the authors intend it to or not. It’s just that some writers are convinced that what they are doing is fundamentally different than what the map-drawing, language-inventing fantasy writing rabble do.

Somewhat less gently, I am also going to suggest that it’s a probably not a coincidence that many of the haters are straight white men. It’s easy to tell yourself that you’re above all that names-full-of-apostrophes nonsense when you mostly read things produced by a literary environment shaped around people like you, for people like you, that treats your perspective as default, your experiences as innate, and your voice as authoritative. Under those circumstances, it’s easy to claim that your stories come about naturally, but everybody else’s are forced and artificial.

But here’s the thing: spending time with fiction that is very much not for you is not just good for you as a person, in some vaguely philosophical sense of learning not to be an obnoxious dick, but it is also ruthlessly, pragmatically good for you as a writer. When you don’t automatically understand the basic cultural foundations of a story, you have to pay attention to what the characters say, what the authorial voice says, what the actions and consequences say, and whether all those things are in agreement. You have to pay attention to the assumptions that are built into every choice, to the personal and political consequences, and how it all adds up into triumph or tragedy.

You have to pay attention to what matters in a fictional world, because without understanding why characters make the choices they do, you won’t be able to understand the difference between a story that falls flat and one that has profound emotional impact. And understanding it in other people’s stories is a key step toward understanding it in your own.

You Can Have as Many Genres As You Want, However You Want Them

Let’s step back to think about the bigger picture for a moment. Because, alas, we can’t just begin a story and create a world and be done with it. We actually have to write the damn thing! I know, I know: It is unfair.

One helpful trick is to be aware that you are never writing just one type of story. No matter how your story might eventually be marketed or labeled, no matter what genre you are aiming to engage or subvert, the process of writing is one of collecting what you need from many different kinds of stories to effectively shape the new one that lives in your head.

Remember, the goal is to make the audience care, which means opening as many doors as possible to allow them in. When this is done badly and the genre-blender doesn’t work, we resent the manipulation; it leaves us annoyed that there is say, a romance tacked onto a thriller that doesn’t benefit from it, or when a story about saving the world keeps getting sidetracked into unnecessary family melodrama.

We don’t notice it quite as obviously when it does work. We can describe a story like MDZS as “romance” and “fantasy,” but in truth it is constantly blending other types of stories. One could argue that the two primary foundations are in fact a family saga woven into a war story, plus a revenge thriller laid down underneath a murder mystery, but there are also pieces of teen friendship adventure, dark psychological domestic thriller, political intrigue, zombie horror, ghost story, and more.

What this does on a mechanical level is allow us to enhance parts that might not feel rich and engaging otherwise, if every aspect were required to fit into the structure expected of fantasy or romance. What it does on an emotional level is let you focus keenly on exploring what different characters do in different situations.

Because, after all, when we strip away all of the fluff and sparkle, stories are really just about people doing things in situations.

No Man Is An Island, Because Every Man Is Jin Ling’s Uncle

There are a lot of characters in MDZS. People are doing things in situations all over the place. That’s normal in big fantasy! We revel in it! Part of why we love such stories is the grand scale, not just in time and geography, but in the fraught and complicated connections between characters, such as when roughly half of the main cast can be described as some sort of uncle to one sad teenager who isn’t even the protagonist.

On one level, yes, we have an epic romance about two people finding and losing and finding each other again. But it’s not only a story about those two people and their relationship. While Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji are making heart-eyes over their canonical love song that was composed in the cave of a mythical giant tortoise, they are both inextricably linked to all the people around them: their siblings, their parents, their mentors, their juniors, their sects, their enemies. The same way all bodies in a solar system are held together by gravity, the characters are all connected in such a way that what happens to one person or group affects all the others, not just immediately but across multiple generations.

When the characters are connected by a web of overlapping and shifting interactions, it allows for myriad types of relationships: romantic partners, siblings, parents and children, sworn brotherhoods, found families, devoted friendships, hated enemies, unhinged obsessions, etc. Offering up so many different relationships provides potential access points for all different kinds of audiences; somebody who might not be into one kind of story will still find something else to engage them.

But even more than that, it invites the audience to imagine what the story would look like from any given character’s point of view, to wander down paths that never show up on page or screen. In doing this, we start to spring all the traps we’ve set to hook the audience’s emotions. People feel stories more deeply when what they’re feeling is a result of active resonance, rather than passive absorption. And if they can feel that resonance from multiple parts of the story? Even better.

Reconsider Your Need For a Big Bad by Instead Giving Everybody Their Own Bespoke Bad in the Form of Problems That Have No Good Solutions

Okay, but what about plot? Advice about plot is very confusing. One person will say that plot ought to be planned out precisely down to every beat in every scene. The next will say it doesn’t exist at all. Isn’t it just things happening? I’m pretty sure it’s just things happening. It’s probably best if those things are happening for some reason. Many SFF stories are built around big, central reasons: empires to defeat, dark lords to overcome, worlds to save, societies to reform. All of which is fun and fine, sure, I like to lust over defeat a dark lord as much as anyone, but there is also value in thinking about how we can shape a story if we don’t have a singular goal sitting at the center.

Buy the Book

The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories

It’s not obvious from the start, but there is no big villain to defeat or catastrophe to prevent in MDZS. Sure, there’s a ruthless dude who starts a war to seize power, and when he’s dispatched there’s a sleazy dude who fills the power vacuum, and there is least one unapologetic mass murderer just kinda hanging around doing his own thing, not to mention that the adaptations tend to fiddle with the villainy levels of several characters in different ways. But there is no one bad guy whose removal would solve all the problems. There’s no huge catastrophe to be averted, no doomsday to be stopped.

What we do have, of course, is Wei Wuxian, who is known as a villain within the story (he’s resurrected because somebody wants a malevolent spirit to do some nasty shit), but that is very much not the same thing as being the actual villain. Again: what the characters in the story believe is a deliberate distortion of what’s actually going on.

So instead of looking at the role each character plays in working toward or against a common goal, “Avengers Assemble!”-style, let’s step back down to some more fundamental character questions: What do they want as individuals? What’s stopping them from getting it? What happens if they don’t get it? What happens if they do? And—this part is key—what happens when these desires and obstacles are in conflict with each other?

It’s really easy to do this with MDZS, which is why it’s such a great example to use for studying how a story arises from multi-layered character conflict. For example, Lan Wangji’s primary goal is to protect Wei Wuxian, which puts him into conflict with everybody who has ever so much as looked at Wei Wuxian funny (eg., enemies, teenagers, fluffy dogs), as well as with Wei Wuxian himself, who has the admirable self-preservation instincts of somebody who dies in the prologue of his own story. Both Wei Wuxian and Jiang Cheng share the primary goal of wanting to protect the people important to them, but the way they go about it puts them into direct conflict—a conflict that is at its most painful when they are in fact trying to protect each other. Wen Qing also wants to protect her loved ones, only for her that means conflict with both those who are endangering them and those who are protecting them. Jin Guangyao wants respect and security in a world that doles out those things according to familial status, not individual ability. Lan Xichen wants to lead with kindness and understanding while surrounded by fellow leaders who really don’t care much for either.

I could go on and on, all the way down the entire character list, but the point is this: when all of your characters are linked not by a single unifying goal, but instead by a tangled web of conflicting relationships and desires, you have endless opportunities to stick them in situations in which there is no easy way out. In which somebody is always going to get hurt. In which desperately trying to do the right thing can still end in tragedy. In which you get to cackle with evil glee while your readers agonizing over every new development, absorbed with all the doubts and dangers, so invested in the emotional fabric of the story that they have to see it through to the end.

That doesn’t mean you can’t still fight doomsdays and evil empires! Nor does it mean every story has to do this to the same extreme; Mo Xiang Tong Xiu very obviously set out to write a story about how trying to do the right thing can still end in unspeakable calamity (but also a story in which unspeakable calamity does not render one undeserving of love and happiness). The question of scale is entirely up to you. It’s the array of choices that matters—well, that and the heart-wrenching feeling you can create when none of those choices are easy.

Instead of Killing Your Darlings, Why Don’t You Let Them Drag You Out of the Ditch Where You Lay Dying Alone and Unloved and Tenderly Care For Your Wounds Before You Gaslight Them Into A Years-Long Domestic Partnership Co-Raising A Teenage Con-Artist In An Abandoned Funeral Home?

There’s this subplot in the story that fans affectionately call the Yi City Arc. (Netflix translates “Yi City” as “Coffin Town” which will never not be funny.) It kinda…doesn’t really have anything to do with the main plot. It’s like a glimpse into an entirely different story. It features characters who are largely irrelevant to the rest of the story. It involves a lengthy and multi-layered flashback that reveals nothing about the larger story. It involves a ghost, a zombie, and a quasi-love triangle with a very high body count. It pretty much exists just to make you feel awful and ends on the bleakest fucking note you’ve ever seen.

But listen: It is amazing.

It’s so amazing that for a long time I didn’t really think about how strange it is to have a diversion like that in a novel. Maybe not so much in Chinese webnovels, which are delightfully unrestrained and often run to hundreds of chapters, but in many other realms of writing, where an editor would have told the author to cut it out, or the author would have cut it out in anticipation of being told as much.

Because, the reasoning would go, it is unnecessary. It’s not essential. It serves no purpose. That’s a notion that many modern authors have internalized so deeply that it is considered an obvious truth. Cut out everything that doesn’t directly advance the plot. Cut out everything that isn’t part of efficient forward-motion. Cut out everything that doesn’t change the main characters. Cut out what isn’t necessary.

Look. This is a book about a guy who raises zombie armies by playing the flute. There’s a purple lightning whip and a Tortoise of Slaughter and a mass grave where the dead are trapped in a pool of blood. The entire effects budget for the live action adaptation was spent on lace front wigs. None of this is necessary. It’s not vitamins. (I mean, it is vitamins for my soul, but never mind that.)

I don’t know why necessary has become the judgment by which we measure every aspect of our stories. I think it is the wrong language entirely for talking about art. And, like, all unpleasant things about modern publishing, I suspect it has to do with marketing and money and aggressively reframing all creative works as sellable content, rather than anything to do with actual artistry. Or maybe we can blame the CIA. I don’t know.

But we’re telling stories. Not producing content. Not writing abstracts. Stories! We are literally making shit up and beaming it into other people’s heads! And our job is to make readers believe those stories wholeheartedly and passionately, if only for a short while. I am not suggesting we all ignore pacing and editing and focus; those things are important and can take on infinite forms. What I am doing is softly entreating that we also remember that writing a good story does not require stripping out everything you love about it. The first and most important judge of what will effectively beam your story into other people’s brains is you. You are choosing the pieces that you want to show the world. You don’t have to pare away everything that makes your story feel rich and alive and whole to you just so it can fit into somebody else’s box.

Do You Need Those Rules As Much As You Need That Giant Army of Reanimated Corpses?

People write fiction for all kinds of reasons. Personal, social, intellectual, political, monetary reasons, whatever, pick however many you want, or define some new ones. The longer I do it, the more I think about how those reasons evolve over time. I used to write because I cared a lot more about being clever, about proving how smart I was, about slipping tricky little puzzles into every story, about showing off my cool ideas, about crafting sentences so beautiful they sing.

I still like to do all those things, sure, but now I view them more as stepping stones on the way toward goals that are both bigger and more nebulous, like having fun, or making a small corner of the world more interesting, or chipping away at the numbing ennui of modern existence, or punching people in the feelings. Mostly all of the above.

One of the most common bits of advice to pop up wherever writing is discussed is, “You have to know the rules before you can break them!” It shows up everywhere. It’s probably going to show up here. (I can see your fingers twitching toward the keyboard, Kevin.) Is it true? I don’t know. I’m not sure I really care. I wonder if both the assumption of rules and the condescending permission to break them miss the point. I wonder if, once again, we’re using the wrong language to talk about what we’re doing.

And so, after spending approximately four thousand hours thinking about cheerful necromancers and their armies of the dead, the scholarly conclusion is one that is both very obvious and somehow very easy to forget:

When writers get mired in seeking advice and finding refuge in rules, we can all benefit from taking a breath and asking ourselves, sincerely, without any room for internal dishonesty, exactly what we are trying to achieve and why. Then look around to find things that will help us figure out how to do it. Then do it.

(We still can’t skip that last step, alas. It remains staggeringly unfair.)

Kali Wallace studied geology and earned a PhD in geophysics before she realized she enjoyed inventing imaginary worlds more than she liked researching the real one. She is the author of science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels for children, teens, and adults. Her most recent novel is the science fiction thriller Dead Space. Her short fiction has appeared in Clarkesworld, F&SF, Asimov’s, Tor.com, and other speculative fiction magazines.