Recently, I was one of the guests of honor at Mythmoot, an annual speculative literature conference hosted by Signum University. That is a sentence I still feel like I haven’t squared with properly. I was asked to give a keynote, to share the metaphoric stage with Dr. Faith Acker, Dr. Michael Drout, Dr. Tom Shippey, and of course Signum’s president, Dr. Corey Olsen (aka the Tolkien Professor)—all scholars, professors, and industry luminaries. I can scarcely wrap my head around it all even now. In that same company were dozens of attendees and other presenters who gave illuminating and well-researched talks. It was an amazing experience and a memorable weekend.

Mythmoot rolls around every June and is usually hosted at the National Conference Center (NCC) in Leesburg, Virginia. If you’re interested in future conferences but can’t make it, you can attend digitally. They’ve been making it a hybrid (in-person and remote) event for two years now. Signum University also hosts a number of smaller regional “moots” throughout the year—like Mountain Moot (CO) in September, New England Moot (NH) in October, or even their first overseas one coming next January, OzMoot (Brisbane, Australia). Well worth looking into!

So anyway, this year was Mythmoot IX, and the theme was Remaking Myth. With Signum’s blessing (and of course Tor.com’s own approval), here follows a contextually adjusted writeup of my Mythmoot keynote on this theme, which I titled “Dungeons & Dragons & Silmarils; or, The Modern Mythologizer.”

Oh, but first. About that theme, Remaking Myth. What does that mean? Well, the Mythmoot XI page described it like this when they sent out a call for papers:

Writers are simultaneously makers of new mythologies and remakers of timeless tales. Their skills in creation show us that the same stories return again and again, from one era to another, from one culture to another, in hundreds of guises across dozens of worlds. Our contemporary tales draw from sources as diverse as ancient manuscripts and timeless oral traditions to the latest release from Disney or Pixar—which in turn reimagine earlier stories, and so on, in endless iterations. A Greek goddess may show up in a Medieval morality play, on the Shakespearean stage, or on the streets of Chicago wearing jeans and a T-shirt. Dragons still roar and burn their way through contemporary children’s picture books, YA novels, HBO series, and serious literary fiction from ancient times to the present. Hobbits have wandered into worlds other than Middle-earth. Humans keep on telling and retelling myths and legends even while the world around us changes: Why? Why does King Arthur keep appearing in animations and allegories and anime? What is the timeless appeal of certain tales? What archetypal essence remains throughout a character’s evolution? And how do stories change in the telling?

My fellow keynote speakers were excellent. Faith Acker’s talk was “Remaking the Myth of the Good Servant,” tracking and comparing characters like Samwise Gamgee, Enkidu from Gilgamesh, and Eumaeos from The Odyssey (among others!) in their roles as faithful servants in well-known tales of old. Michael Drout spoke of Beowulf and Tolkien’s preference for “history, true or feigned” over allegory. Tom Shippey discussed real and fictional cities in popular urban fantasy, like London Below from Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere and monster-haunted Chicago in Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files series.

There were presentations on magical theatrics; Ursula Le Guin’s maps; the recurring role of prophecy in speculative fiction (in The Dark Crystal as much as Tolkien!); the healing power of fairy tales (best illustrated in The Princess Bride), and the use of air power in Tolkien’s legendarium. And don’t get me started on Christopher Bartlett’s tear-jerking composition and recitation “Of the Reuniting of Beren and Lúthien.” Someone would not stop cutting onions in the room during that one, I can tell you. Memorable talks and gratifying conversations throughout.

Well, here’s more or less what I came up with for my talk…

Dungeons & Dragons & Silmarils; or, The Modern Mythologizer

What are creation myths but the ultimate prequels—the tales that precede all the tales we tell today? Old myths and legends are the start of era-spanning chain reactions of the imagination. And every time we revisit one, we have the opportunity to ask new questions of it, or to reimagine it outright.

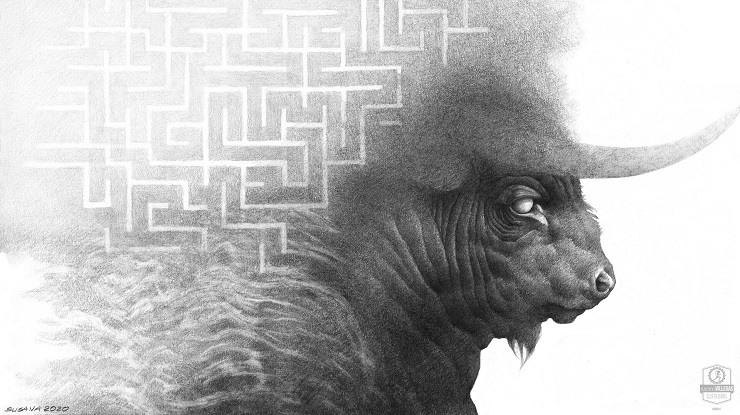

What if, when the Minotaur met Theseus, instead of getting himself slain, he teamed up with the famous son of Aegeus and they escaped the Labyrinth together and went on seafaring adventures, buddy-cop style? Better still, did so with Ariadne, the Minotaur’s mostly-human-but-kind-of-divine half-sister—because siblings really ought to stick together.

Or what if Medusa wasn’t one unfairly cursed woman but the name of an entire race of civilized, highly intelligent, and secretive stonemason-architects who put to cunning use the petrifying power of their gaze? Yes, their eyes would still be deadly and they can turn trespassers to stone, but what if, within their own culture, they used this power more as a tool than a weapon? A dying elder medusa or a close friend who is mortally wounded could be preserved in stone, saved from true death.

On that note, I would argue that when you sit down to play a session of Dungeons & Dragons, or recount any folktale, or fable, or legend—or even, say, relay the events of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion to an audience—you are mythologizing in some way. Intransitively. See, the Oxford English Dictionary says that if you’re mythologizing, you are “recounting a myth or myths.” Merriam-Webster adds that you’re “creating or perpetuating myths.” We’re not even using the word myth in the modern sense, as when one dispels or propagates a myth, meaning “an unfounded or false notion.” As in the phrase: the myth of Balrogs’ wings.

No, here we’re running with the OED’s first definition:

A traditional story, typically involving supernatural beings or forces, which embodies and provides an explanation, aetiology, or justification for something such as the early history of a society, a religious belief or ritual, or a natural phenomenon.

Aetiology just means cause or origin. When it comes to the Oxford English Dictionary, you need to have a dictionary handy!

In plainer words, myths are a way to see where a group of people came from—historically, culturally, psychologically. They’re stories from somewhere out of the past (or at least written like they were, like Tolkien’s) that have societal meaning and staying power. By their very nature, they’re meant to be retold, recast, and revisited—perhaps even refurbished or reupholstered? But they are fluid things; they change as we do, and as the world does. And we’ve been retelling myths since the first was spoken out loud. It’s just in our DNA. As soon as one person finishes telling a great origin story, someone else runs off and tells it to another, kicking off the everlasting, humanity-spanning game of mythological telephone that we still enjoy today. Heck, some myths are about how such stories even get started and spread.

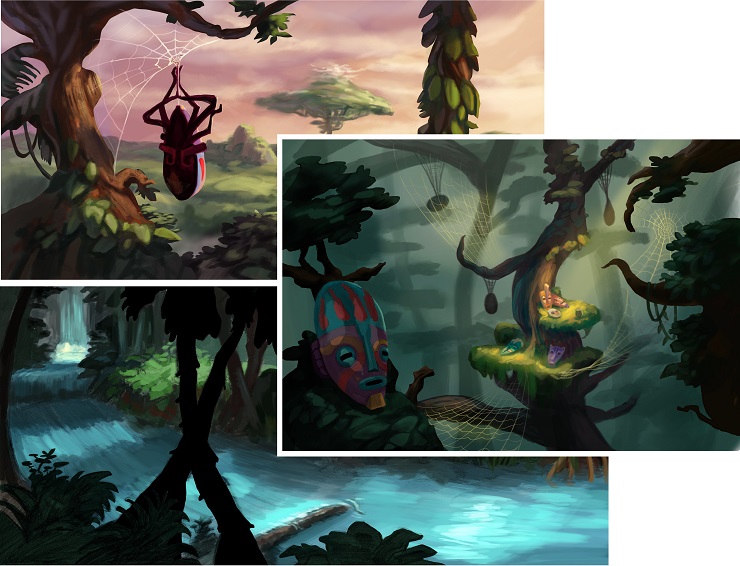

In the Ashanti myths of West Africa, there is Anansi the spider: a shapeshifting culture hero, sometimes a kind of god himself, but always seen as a wise yet mischievous trickster (not unlike Ma’ui or Coyote). Being an underdog, Anansi uses his wits to overcome obstacles physically greater than he. He often intercedes on behalf of humanity, causing chaos but bringing much-needed change.

In one such myth, long ago, humans were bored, and knew nothing of their own history. That’s because the sky-god, Nyame, possessed all the stories in the world—stories being magical things that could bring happiness and meaning. So Anansi spun his web up into the heavens and made a bargain with Nyame, who in exchange for the stories required him to capture four impossible-to-catch things: a deadly hornet swarm, a killer python, a stealthy leopard, and an elusive forest fairy. Using his smarts, Anansi succeeded, and thereby purchased all the stories from the sky-god. Anansi then brought them down to the world to be shared with mankind. Thus we have a story that explains how we have so many stories. Very meta.

Now, I don’t intend to just relay a bunch of myths, merely to point out how some have been remade and that it’s worth doing so ourselves. All the old myths come with cracks and hollows, spaces for us to explore and seek new meaning. What isn’t said in the original that we can ask about? What can we change to make it more relatable? Anyway, who tells any story exactly as it was told to them? Nobody, is who. We never just copy-and-paste the things we love when we share them. So whether we’re rewriting a myth or setting out to invent a new one—by creating art, by writing a story, by playing a roleplaying game—we instinctively leave our mark.

First, let’s look at a few familiar examples of myths remade in history. Starting with some monsters. Like the winged sphinx of Greek myth…

and “Sphinx” by Nathan Rosario (Used with permission by artist.)

She was a singular creature who prowled around outside Thebes, devouring travelers who couldn’t answer her riddle. I’d say Gustave Moreau’s “Oedipus and the Sphinx” painting takes it a step further, invading her would-be victim’s personal space like a real cat, whether to annoy him, whine for food, or ask him a riddle. But see, the sphinx had been imported from Egypt and repurposed. Back in Egypt, the sphinxes, plural, weren’t chomping on anyone in the stories (that we know of), just guarding temples and tombs; they had the faces of pharaohs and queens and were—like Balrogs—usually wingless. Through trade and cultural cross-pollination, sphinx-like creatures started popping up everywhere: In Persia, in Assyria, all across Asia… Carved in stone, they became benevolent guardians, warding off evil, not unlike the gargoyles centuries later spouting rain water from the sides of medieval churches. (Though, gargoyles were also meant to illustrate evil. Topic for another day, maybe.) Ah, but even ’goyles existed in pre-Christian times, after a fashion. They were more lion-mouthed prototypes, and both the Egyptians and Greeks had them first.

Speaking of the Greeks, let’s go back to the Minotaur, whose tale was adapted from the rituals and relics of the Minoan culture that preceded them on the island of Crete. The Minoan reverence for bulls, their art of bull-leaping, their mazelike dances, and their many-chambered palaces birthed the legend of the labyrinth and its monster. In fact, the frescos discovered in the ruins of the Palace of Knossos make bull-dancing (not to be confused with bull-fighting) look impossibly hard but quite fun. Everyone’s having a great time? Maybe the bull isn’t? But they did revere their beasts.

Then there’re the Romans who followed. They famously borrowed the heroes, monsters, and gods of the Greeks they conquered. Sure, they already had some deities of their own—like Janus, the two-faced god of transitions, beginnings, and ends—but over time the Romans assimilated most of the pantheon. Some gods were tampered with more than others. Dionysus was the Greek god of wine, revelry, and impulse, but the Romans rebranded him with one of his epithets, Bacchus, and merged him with Liber, the god of freedom. Others they kind of just kept as is, like Apollo, the god of light, truth, and prophecy. (Remember these last two for later.)

Zeus was absorbed into Jupiter, Aphrodite became Venus, Heracles became Hercules, and so on. But in “remaking” these divinities, the Romans made underlying cultural changes. Their gods were aloof by comparison, associated more with material objects, and had their human-like physical characteristics de-emphasized. Then again, sometimes the Romans reversed things. Like how they took Eros, originally a Greek primordial god, parentless and lacking a humanlike form, and reimagined him as Cupid, the god of love and the son of Venus. He became enmeshed in mortal affairs and eventually found his way to us in the twenty-first century as a…matchmaking baby archer.

Because that’s a lot cuter on Valentine’s Day cards? The poor bastard.

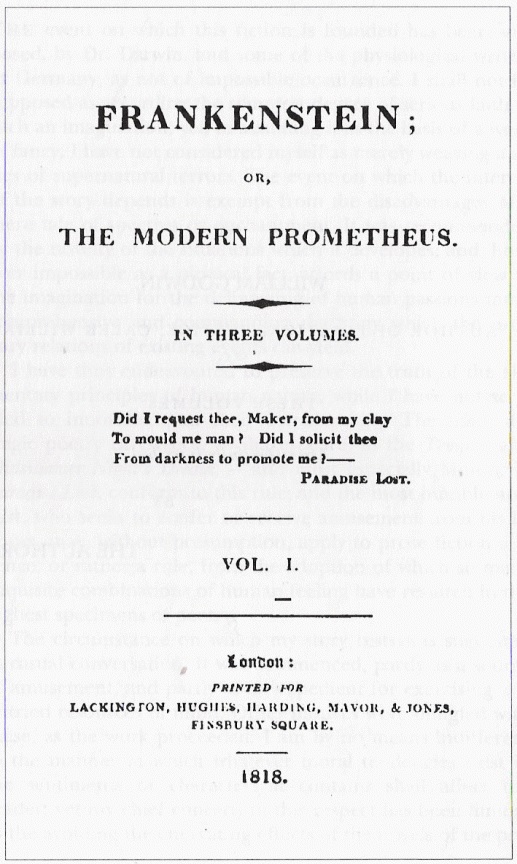

Of course, it’s not like it was only whole cultures that recast the myths of others. Sometimes lone individuals did so. Like, say, a nineteenth-century Gothic novelist who just happened to invent the genre of science fiction. Cue Mary Shelley with her book:

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. So, it looks like Shelley may have been borrowing that subtitle from the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who in turn seems to have coined it with Benjamin Franklin in mind, but that’s all part of the great telephone game. Obviously, Shelley’s tale isn’t a retelling of the deeds of the Greek Titan Prometheus. It is a borrowing of that myth’s conceits—creation and the subversion of nature. Yet she took things another direction, making her novel more of a cautionary tale.

Most writers and artists in her time saw Prometheus as a culture hero (like Anansi). First, he formed man out of inanimate material (clay), which alone qualified him as a stand-up guy. He made a thing! And he liked it! But where the gods would have had mortals just barely scraping by, subsisting on their fickle gifts, Prometheus went to bat for them. Defying Zeus, he stole what wasn’t technically his to give (fire, i.e. the power to harness nature) and gave it to mankind with good intentions. He loved his creations and wanted them to prosper. Yet he went on to suffer grisly consequences for his actions.

and “Gift of Fire” by Silkkat (Used with permission by the artists.)

Meanwhile, Victor Frankenstein, a student of natural science, creates a humanlike creature from inanimate materials (likely dead tissue from “the dissecting room and the slaughter-house”). He, too, takes what isn’t his to give (the spark of life itself!) and he uses it to animate his 8-foot lab experiment. Now, Victor’s intentions are not selfless like those of Prometheus. He pursues his studies for his own purposes and he very markedly doesn’t love his creation in the least. In fact, he runs from responsibility rather than facing it right from the start, when “the wretch” at last moves and stands over him, seeking understanding. Victor runs from responsibility several times, actually. Despite what Hollywood has done with him from time to time, the creature is neither a great force of evil nor a rampaging monster; he does take his vengeance, though, by murdering only the people his creator loves. Hence Victor suffers grisly consequence for his actions.

One might say Mary Shelley galvanized the Prometheus myth, giving it new life, which has of course inspired countless retellings of her own tale in all mediums, which all in turn have spawned countless more spin-off concepts.

Not the least of which is Sally and Dr. Finkelstein from The Nightmare Before Christmas. Just saying.

Man, I am such a Frankenstein fanboy. Topic for another day.

Anyway, the Sphinx, the Minotaur, the Roman gods, and Victor’s “daemon” are just a few of a zillion examples of remade myths in centuries past. But let’s jump forward to the twentieth century and the present. For my part, I’m looking mostly at J.R.R. Tolkien and his legacy, so I’d like to start with some of his remade myths. Particularly those in The Silmarillion.

But first I want to acknowledge the challenge that book poses and the need, I felt, for “remaking” it. Maybe not remaking; repackaging. See, I started the Silmarillion Primer series here on Tor.com back in 2017 because I always felt more people ought to know about it. It’s a famously formidable book even among fans of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. There are real barriers to entry, some of which have to do with expectations. Consider this 1977 criticism from a review by author John Gardner in The New York Times:

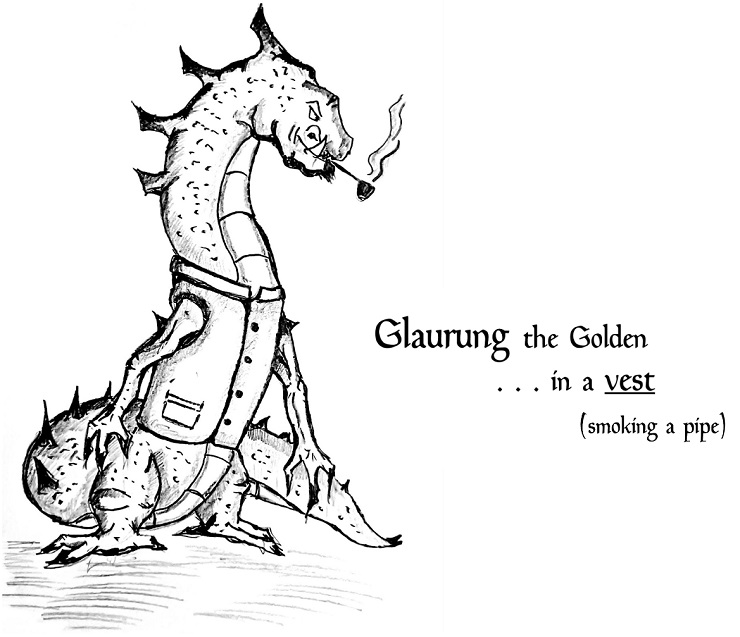

The central tale…has a wealth of vivid and interesting characters, and all the tales are lifted above the ordinary by Tolkien’s devil figures, Melkor, later called Morgoth, his great dragon Glaurung, and Morgoth’s successor Sauron. Numerous characters here have interest, almost always because they work under some dark fate, struggling against destiny and trapping themselves; but none of them smokes a pipe, none wears a vest, and though each important character has his fascinating quirks, the compression of the narrative and the fierce thematic focus give Tolkien no room to develop and explore those quirks as he does in the trilogy.

Which is…fair.

Glaurung the Golden, the Great Worm of Angband, the father of dragons, slayer of Elves and Men, bane of Azaghâl the Dwarf-lord of Belegost, dragon-king of Nargothrond…

…very likely did not wear a vest.

But it’s true. As published, The Silmarillion leaves little room for the “quirks” that John Gardner was referring to. Thus it falls to us to ask what else fills in those cracks and hollows. Meanwhile, that same year, the book was called a “stillborn postscript” to The Lord of the Rings by The School Library Journal; it was called “pretentiously archaic” and “at times nearly incomprehensible” by Newsweek; and a reviewer in UK’s New Statesman who clearly didn’t like Tolkien in the least wrote that he “can’t actually write” and that he is “an unadventurous defender of mediocrity.”

Of course, we know better. Yes, the text is lofty, and even more archaic in mode and style than The Lord of the Rings. At least that’s how Tolkien began it; we can see from his later writings (especially in the recently published The Nature of Middle-earth) that he intended to circle back and rewrite the ‘Silmarillion’ as a more boots-on-the-ground fantasy romance like The Lord of the Rings. Had he actually done so, the stories of the Elder Days of Middle-earth would have become, perhaps, far less mythic to us. (And maybe more widely read.) But he did not, and so what we have is this primeval drama of Arda’s past presented in a higher mode.

As for where his ‘Silmarillion’ mythologies come from, well, plenty has been said and written, I know. But for this discussion, I’d like to begin with two sentences from Tolkien’s famous 1951 letter to Milton Waldman:

These tales are ‘new’, they are not derived from other myths and legends, but they must inevitably contain a large measure of ancient wide-spread motives or elements. After all, I believe that legends and myths are largely made of ‘truth’, and indeed present aspects of it that can only be received in this mode; and long ago certain truths and modes of this kind were discovered and must always reappear.

So what Tolkien tells us here is true…from a certain point of view. Even so, he speaks to the inevitability of myths being remade, again and again. And it does seem evident to most of us that in crafting his secondary world, Tolkien cherry-picked, as we all can, from primary world myths, legends, and fairy tales. Or at least, as he would prefer it said, from the same “truths and modes” that spawned the original real-world myths. But here’s the thing. Even when Tolkien’s ‘Silmarillion’ myths—let’s say—bore some resemblance to other myths, his usually featured an inversion of their elements.

Take the Valar, “whom the Men called gods.”

The Valar are not direct analogues of any real-world deities, but they do seem inspired by such pantheons. Manwë, the King of the Valar, is not Zeus, nor Odin the All-father of Norse legends. But the kingly authority of such mythological figureheads can still be seen in Manwë. Aspects of Odin can even be found in Gandalf, not the least of which is his sometimes “disguise” as an old wanderer in beggar’s clothes.

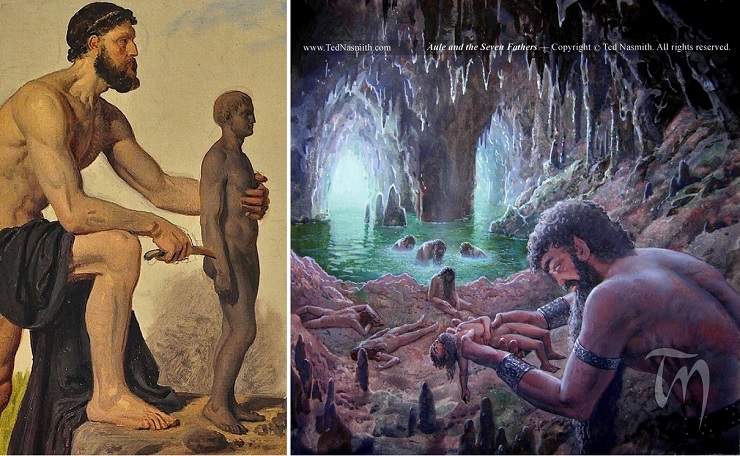

The water-loving Ulmo might seem like Poseidon at first glance, the great smith Aulë like Hephaestus, or nature queen Yavanna like Demeter. But the “gods” of Tolkien’s world lack the human impulses, the petty grievances, and the chronic infidelity of the Greek Olympians. This lifts the Valar above that mythic “ordinary,” makes them more akin to angels, even if Tolkien was reluctant with that term. And like angels, they are subordinate to their own creator: Eru Ilúvatar, the God of his legendarium. Not so the Olympians, who actually overthrew their parents—yet they were just as flighty as the mortals they ruled over, just far more powerful. And where Zeus and Odin commit many acts of violence, Manwë, Tolkien wrote, “was free from evil and could not comprehend it.” Likewise, Aulë the Maker (who is called Mahal by the Dwarves) had pride only in the love of his craft and never in possession itself. Whatever he made, he gave away freely to others, so he could start on the next project. Speaking of Aulë…

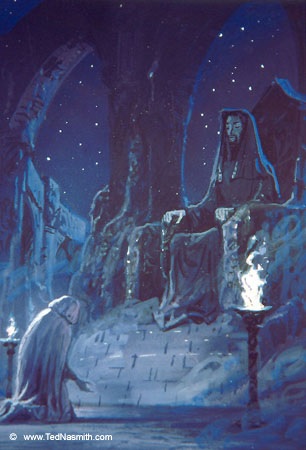

and “Aulë and the Seven Fathers” by Ted Nasmith (Used with permission by artist.)

In Aulë’s creation of the Dwarves, you can see a bit of that shaping-people-from-the-substance-of-earth approach of Prometheus again. Now, did Tolkien mean to invoke the Greek Titan directly? Probably not, but the “ancient wide-spread motive and elements” are there, just as they are in the making of Adam in the Abrahamic traditions. Sumerian and Egyptian mythologies had them, too, and many more.

And while there may be no direct link, I’ve always seen some of the same ingredients at work in the 16th-century legend of the Jewish Golem, which was fashioned from clay by Rabbi Loew (the Maharal of Prague) to defend the Jews from persecution. Even though the rabbi’s piety and his considerable mystic knowledge could animate the Golem, he could not give it free will, nor a soul. It could only follow specific directions, ultimately to a fault; this imperfect control eventually led to a murderous rampage that forced Rabbi Lowe to deactivate the Golem for good. Only God can breathe true life into a created being, is the lesson. Tolkien makes this super clear in his myth. The Valar themselves cannot do it. Ilúvatar points out to Aulë that his newly crafted Dwarves would only be able to move at all if he wills them to, saying…

therefore the creatures of thy hand and mind can live only by that being, moving when thou thinkest to move them, and if thy thought be elsewhere, standing idle.

Like puppets. Only when Ilúvatar himself accepts the Dwarves, which he does almost immediately, does true life imbue them.

In her book Splintered Light, Dr. Verlyn Flieger draws a comparison between Fëanor and Prometheus—yes, Prometheus strikes again! She describes them both as overreachers whose “excess” is punished yet whose accomplishments brought a “spark to humanity that can elevate it above its original condition.” Which is spot on, of course. Prometheus brought fire to the world and, as Dr. Flieger writes, “Tolkien makes sure that images of fire in all its negative and positive associations attach to Fëanor from his very beginning.” But just as Tolkien’s mythological influences are seldom one-to-one, I find both the intrepidness and the fate of Prometheus extends beyond just Fëanor. In fact, it ropes in the character of Maedhros, Fëanor’s eldest son—in whom, Tolkien wrote, “the fire of life was hot.”

To say nothing of the fact that Maedhros eventually meets his end in “a gaping chasm filled with fire.”

Now, for his crime of defying Zeus, stealing fire, and giving it to mankind, Prometheus was chained to a mountain. Each day, the sky-themed king of the gods sent an eagle to devour the Titan’s liver, which would regenerate during the night so it could be torn out anew. The eagle is an instrument of punishment and pain.

Meanwhile, for his crime of defying Morgoth and, well, being an Elf (not to mention being Fëanor’s kid!), Maedhros was captured and bound up on one of the Dark Lord’s own foul mountains. He was kept alive, hanging from his wrist and no doubt starved in daily torment, yet his rescue was achieved with the help of an eagle sent by Manwë, the sky-themed King of the Valar. It is an act of mercy and partial forgiveness on his part; Tolkien’s eagles are an instrument of salvation (and eucatastrophe, for those familiar with that term), and so again it’s quite clear—in case there’s any doubt—that the Valar are not Olympians.

Despite the imaginary visual parallels.

Now let’s scale things down a little bit and look at a simple, damsel-in-distress fairy tale. To which Tolkien seems to have said, “Oh, neat ideas! But it needs fixing.”

We see an echo of Rapunzel in the Beren and Lúthien story. Rapunzel’s tower is accessed when her surrogate-mother, the very witch who imprisoned her there, commands her to let down her crazy-long golden hair so it can be climbed up. Or, in the translated Grimm tale, calls out this rhyme: “Rapunzel! Rapunzel! Let down your hair / That I may climb thy golden stair!” The witch visits her adopted daughter regularly but keeps her caged.

Meanwhile, over in Middle-earth, the Elf-princess Lúthien is imprisoned in a tower-like treehouse (the great beech Hírilorn) by her own possessive parent, the Elf-king Thingol. Her dad does this because he knows his willful daughter wants to run off and try to save her mortal boyfriend from the clutches of Sauron—which he really doesn’t want. I mean, there was a reason the Elf-king sent that good-for-nothing mortal Beren off on an impossible quest!

Yet to Tolkien, Lúthien is no damsel-in-distress but the hero of her own story. She is not the love interest to Beren; they are both protagonists who get things done, who have a high destiny, and while they sometimes contend with one another (for love’s sake) they always end up working together. It could be argued that the more productive of the two is Lúthien, for whom Tolkien’s wife, Edith, was an inspiration. Thus she escapes from bondage under her own power. Lúthien “puts forth her arts of enchantment” to grow her crazy long black hair, weaves a shadowy magical sleep-cloak with it, then braids the leftovers into a super-long rope so she can climb down. At which point she runs off to go rescue her boyfriend from the dungeons of Sauron.

Okay, but let’s scale back up again for just one more of Tolkien’s remade myths.

We see traces of Orpheus, Eurydice, and the underworld of Hades sprinkled throughout the rest of that same story. Seriously, the tale of Beren and Lúthien is positively dripping with Orphic elements. So the two lovers reach the gates of Angband and are stopped by its massive canine guardian, Carcharoth—reminiscent of Cerberus, the three-headed guard-dog of Hades. Lúthien, like Orpheus, coaxes the beast to sleep, then they descend together through a physical underworld all the way down to Morgoth’s throne room.

There Lúthien puts on a musical performance, singing the entire monstrous court to sleep, and even causes the Dark Lord himself to nod off. Beren pries a Silmaril from the crown that rolls of Morgoth’s head, because that’s what they went there for. Then they make a beeline for the exit.

They do escape, just barely, but not before the aforementioned guard-wolf, Carcharoth, bites Beren’s hand off—Silmaril and all! In battling the great wolf later, an effort that takes a whole team of high-level Elf hunters (including King Thingol himself), Beren is at last mortally wounded. Rent and bitten up by Carcharoth. He dies from his terrible wounds. As a brief aside, Carcharoth is no normal wolf; he’s a werewolf, an evil spirit imprisoned in the body of a ginormous lupine body; moreover, his fangs are venomous. In the Greek myth, Eurydice dies from the bite of a venomous snake—the impetus behind Orpheus’s quest into the underworld of Hades.

Dead now, Beren’s spirit departs and goes to the purgatorial Halls of Mandos—a more spiritual underworld this time. But Lúthien’s not done. She follows suit, and her spirit leaves her body and ventures to the same realm. There, in spirit form, she kneels before Mandos directly to plead their case. Mandos is the Vala of Judgment, the Keeper of the Houses of the Dead. He calls the shots in this realm. So right there before his feet she sings a lament, “the most fair that ever in words was woven, and the song most sorrowful that ever the world shall hear.” Mandos is “moved to pity,” brings the matter to his boss, and secures the couple’s joint release from death. Where Orpheus failed to bring his bride out of the underworld, Lúthien succeeds, restoring her husband (and herself) to the world of the living (if only for a limited time).

Curiously, in Tolkien’s story, the role of Hades, god of the underworld, is essentially split into the persons of both Morgoth and Mandos. Like two sides of the same underworld/afterlife-themed coin. One is evil and rules a physical hell, the other wields just authority and oversees a spiritual realm where the souls of the dead gather. But what is Tolkien doing here? He has said that “legends and myths are largely made of ‘truth’,” so what is the truth he is addressing? When all is said and done, death is one of the most recurring themes throughout his legendarium. For mortals, death is not an evil, just part of the divine plan—the gift of Ilúvatar and a release from the circles of the world. Men thus escape from Morgoth’s corruption, while Elves cannot. They must endure it, and live on, and remember everything. To Elves who are physically slain, the “underworld” of Mandos is just a waiting room before healing and recovery and returning to the world. To men, it is a waystation before leaving the world entirely.

Tolkien doesn’t stop and discuss this with us, naturally. That’s not how stories work. But we can ask these questions along the way and discuss them.

All right. So Tolkien’s invented myths are often a conglomerate of others’ myths fused together then combined with original ideas to make something new and multifaceted. Like Narsil into Anduril (or Anglachel into Gurthang!), Tolkien’s myths are reforged to new purpose, like yet unlike what they were before. Tolkien doesn’t hide the original ingredients—some are obvious enough—he just stirs them into the soup of Arda, and together they make an original new whole.

And yet that whole is often deemed difficult due to his mode of language. A few months ago I conducted an informal survey on social media. I asked what people’s first experiences were with The Silmarillion, particularly those who approached it without help. While most eventually came to love it, in the beginning they first “tried,” “gave up,” “couldn’t get into it,” “bounced off,” “struggled with,” or had to “truck through” it, while others “abandoned” it or only ever “skimmed” through it. I was certainly no exception, back when I first tried. I only understood the main beats of the narrative, if that, for a very long time.

Now, understanding or even just finishing The Silmarillion is still a point of pride to most fans. As it should be! And this is why I made the Silmarillion Primer. I had three personal goals with it:

- To make The Silmarillion more approachable for prospective new readers.

- To entertain those already familiar with it.

- To offer new ways of looking at Tolkien’s myths. Maybe to “air” some of the questions that I had, that maybe others had, too. That was my part in the retelling.

I didn’t intend it to be a CliffsNotes version of the Silmarillion; those are study aids, but students famously use them to bypass the book they’re supposed to be reading. Maybe it would be more like… The Creation of Arda and the Dramas of the Elder Days That, Once You Know Them, Deeply Underscore the Themes of The Lord of the Rings for Dummies. But if so, then I was a dummy, too. The truth is, I never grasped The Silmarillion as fully as when I sat down and started writing about it. The main point being, I absolutely want my readers to learn something from my rendition, then go and read Tolkien’s actual and far superior words, except now armed with some new perspectives, some art, some fun maps, and definitely some diagrams to help visualize the geography and all the Elf sunderings and family trees.

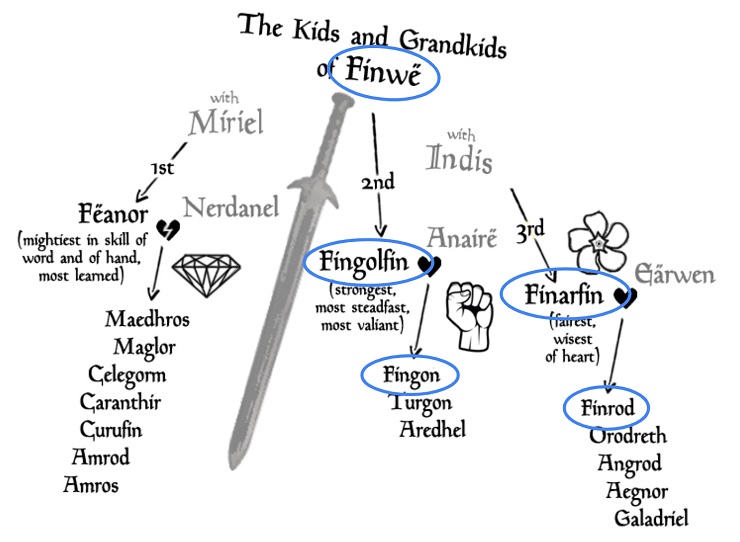

Because those can be a doozy. I’m definitely looking at you, Finwë, Fingolfin, Finarfin, Fingon, and Finrod!

So I attempted not to replace The Silmarillion but to repackage it. To present the stories in a more contemporary vernacular so that a new reader—who might have otherwise found it difficult—could ease into the text when they do give it a try.

Imagine a set of double doors. They’re elegant and tall, but they’re set in a high place with no stairs up. Instead it’s a steep climb up a mountain wall. They say there are amazing things inside, and you can take others’ word for it, but you’d never discover it yourself if you don’t go up. Some people are naturally good climbers, make short work of it, and go right in. Yet not everyone can. But what if there was another way up? What if there was a comfortable ground-level door, which led to a hidden passage that gradually ascended inside the mountain and reached the double doors? And once you’ve made it, you look down and find that the sheer wall was only an illusion all along. There are plenty of easy handholds, and now you know them. You can climb up any time from here on out and explore the wondrous chambers. That’s what I wanted my Silmarillion Primer to be like—that alternative door. That’s my “remaking” of Tolkien’s myths.

By the way, we use these phrases like “myths remade” and “myths retold,” but I’m not sure there are many other ways to approach them. When you’re retelling a myth, you are remaking it. We’re always re-doing something when we engage them. And it’s not like there’s any proper canon when it comes to ancient tales. Sure, we like to argue about what’s canon in modern myths, by which I mean today’s intellectual properties: Star Wars, Harry Potter, Marvel, Tolkien. But it’s not so different with real-world myths. Was it an eagle that devoured Prometheus’s liver, or a vulture? And Pandora’s box? Originally a jar. Or was it?! Before the poet Hesiod got around to writing it down, it could very well have been a casket, a satchel—a waistcoat pocket! Who knows how far back a snippet of mythology like this might go, how many stages of evolution it may have gone through, so far back that the so-called original may barely resemble the story of the box of mischief we know today.

There are so many revelatory myths from around the world worth remaking, but first we’ve got to learn them: from the innumerable oral tales of Africa to The Epic of Gilgamesh to the spiritual kami of Japanese folklore (which, by the way, maybe-coincidentally-but-maybe-not includes a story about a “god” going into the underworld to save his spouse…). I’m an expert on none of those, and have still only seen the tips of their mythological icebergs.

In truth, it is hard to escape the Greek myths. Western culture and language has its siren songs, its Achilles’ heels, its furies and fates, and its narcissists because they’re so pervasive. We echo these old stories and we fly too close to the sun. Even Tolkien—though he didn’t poach from Greek mythology quite as directly or as unabashedly as his friend Jack Lewis—still lets fall the choice word or two. In The Two Towers, his narrator describes the land of Ithilien as keeping still “a disheveled dryad loveliness.”

But in C.S. Lewis’ defense, he did much more than just sprinkle fauns and centaurs into Narnia. In his book Till We Have Faces, he brilliantly remakes the myth of Cupid and Psyche. He centers not the character of Psyche (a mortal woman who would eventually become a goddess), but one of her previously unnamed elder sisters. Through the eyes of Orual, he blurs the lines between mortals and gods, explores what it means to love others possessively rather than selflessly, and just tells an all-around profound story that you wouldn’t get from the original myth. Yet somehow he keeps the original myth’s plot points intact. Retelling a myth without subverting it.

More recently, the novel Circe by Madeline Miller does this exceptionally. She weaves in the threads of many well-known Greek myths through the life of the witch Circe—she is an eyewitness to some and plays a pivotal role in others. With women so often made victims in the original epic poems, Circe gives us a fresh voice and greater agency to its protagonist without making her a villain. She does this without wholly changing things—all characters become more nuanced, filled with virtues and flaws we may have never thought of. Odysseus himself included.

In his short story “The House of Asterion” (1947), Argentine poet Jorge Luis Borges fixates on the utter loneliness of the Minotaur through its own point of view. It’s a very sad but poignant narrative that also reminds us that the Minotaur did have a name: Asterion, which means “starry.” Even Frankenstein’s monster didn’t have a name—that was one of his problems.

Speaking of the Minotaur: For thousands of years, there was just the one—killed again and again with each retelling of the legend. But monsters that cool and/or tragic don’t have to remain static. Yes, there are lessons we can draw from the original story, as with any myth. Like the existential injustice of the Minotaur itself; the heroism of Theseus, despite his questionable later decisions; and the cleverness of Ariadne and her ball of string (from which we get the word “clue”). BUT! We don’t have to remake entire tales. We get to pilfer when it suits us. Why not pluck out just the Minotaur and give him a better imaginary life?

Well, in the 1970s, Dungeons & Dragons came along and started to do just that! Now, D&D rose out of the wargaming hobby and the fertile shadow of Tolkien. And longtime gamers know that the best myths and legends are the ones we dream up and make right at home. In our living rooms or dining room or kitchen tables, even in our Zoom or Roll20 sessions. Wherever!

And what are roleplaying games but one of the best ways to mine from whatever myths we want, people them with our own personalities, and infuse them with personal meaning? They’re not so much games as systems for collective storytelling. It’s deliberate mythologizing with elements of risk (and fun polyhedron dice). From D&D’s early days, you could be a halfling or a dwarf, an elf or a ranger; you could battle giant spiders, orcs, wights, trolls, wraiths; you could flatter and/or fight dragons on their hoards of gold well outside the bounds of Middle-earth…remaking and reinventing the conventions of fantasy of the day.

Right, so, back to the Minotaur. (I always go back to the Minotaur.)

So in the early years of Dungeons & Dragons, minotaurs (plural now) were just one of many types of monsters you could populate your dungeons with: the perfect beasties for a subterranean maze, but still only meant to be slain, evaded, or, at best, riddled with. Like sphinxes! Or manticores or hydras. The Dragonlance campaign setting from the mid-80s was the first to reimagine minotaurs as a civilized race from which heroes and villains alike could be drawn—yet theirs was still a generally antagonistic society. Shout-out to my boy, Kaz the minotaur!

But since the mid-80s, a lot of traditionally evil creatures in Dungeons & Dragons (creatures drawn from Tolkien and all kinds of real-world mythology) have become less homogenized and more independent. So while you can still find minotaurs in the Monster Manual to be fought, you can also play one as a hero. Win-win!

And while I don’t know a whole lot about them, I believe the nomadic, bull-headed tauren of the Warcraft games are minotaur-inspired. And that’s just one creature type. There are tons more with their own trajectories in the many-splintered telephone game we’ve all been playing.

Earlier, I mentioned the Golem of Jewish legend, which certainly inspired D&D’s own early golems: clay golems (like Prague’s), flesh golems (what up, Frankenstein?), then stone and iron golems. Those last two call to mind Talos, the colossal animated statue of bronze from Greek myth. These days, Talos might be best known from his appearance in the 1963 film Jason and the Argonauts, but his tale is bigger than that. And he is arguably mankind’s first imagined robot!

Talos had been commissioned by Zeus for King Minos—you know, the same royal jerk who had a maze-like prison built to cage the Minotaur? (I can’t quit you, Minotaur.) Forged by Hephaestus, god of the forge and invention, Talos was massive and strong, powered by divine ichor, and he was set to patrol the coastline of the island of Crete. He’d throw rocks at trespassing ships. If anyone actually got close, he’d pick them up in a deadly embrace; his bronze body could heat up and they’d be, well, toast. That idea of an animated statue with not-so-obvious special tricks also carried through to the golems of D&D. The iron golem could be healed when heated, while lightning could slow it down; yet it could exhale a cloud of poisonous gas. The stone golem, meanwhile, could magically slow its opponents down just by facing them.

Clay golems, from their first appearance in 1977’s Monster Manual all the way to their 5th Edition incarnation, have always had some chance to go berserk in combat and even attack their creators. Its roots in the original Golem legend are still present. Now, in the old story, Rabbi Loew had carved the word “emet” (אמת, the Hebrew word for “truth”) on its forehead to activate it. Later, he would erase the aleph (א), making the word “met” (מת, or “death”), to deactivate it. Hold onto that image for a moment.

With that said, there is a particular D&D fantasy world I would like to call some attention to, where myths were reinvented again starting in 2004: Eberron.

Wizards of the Coast presented Eberron as a new campaign setting—that is, a new sandbox D&D players could set their stories in. It was a world of Indiana Jones–inspired cinematic action and pulp noir. And techno-magic advancements like airships, mass communication through “speaking-stones,” and even an elemental-powered train system. The whole world manages to combine Renaissance, Victorian, and Cold War aesthetics. All a far cry from Tolkien, obviously, yet the roots of his myths are still there. Such as the sect of druids who call themselves the Wardens of the Wood, who seek to maintain a balance between civilization and nature, and are led by a massive, walking “awakened” pine tree.

Incidentally, Eberron also made minotaurs morally flexible, and did so with nearly every sentient creature of legend—giants and harpies, goblins and orcs—long before it became a matter of course to do so. The hobgoblins of the fallen Dhakaani Empire, for example, were once the more civilized and dominant race on Eberron’s central continent before humans came along. And oh yes, and the medusas of Cazhaak Draal in the “monstrous” land of Droaam are the stonemasons and architectures I mentioned at the start.

But there’s one particular Eberron fixture that really roped me all in. During the course of a century-long war, there came a magical innovation greater than all the rest: the warforged. In Eberron, warforged are living constructs of stone, metal, and wood; they are man-shaped, mass-produced soldiers designed to fight wars so that fewer fleshy, breathing people have to. Their makers, the human artificers of House Cannith, intended them to be intelligent enough so they could be trainable, and adaptable in combat situations but they hadn’t planned on their creations being so gosh-darn sentient, and so individualistic. In fact, when each warforged rose up from the creation forge that spawned it, it bore a unique glyph upon its forehead. Familiar concept, eh? Called ghulra (the Dwarven word for “truth”), these symbols were not part of the design specs at all. Yet there they were; each ghulra, just like each warforged, was unique. Like a finger print, but more prominent.

This presented some uncomfortable yet fascinating questions for their makers, or anyone who interacted with them. Did warforged have…souls? They certainly had minds of their own, and free will. Had some greater power—and not the artificers’ magic—given them real life? How easy it is for a Tolkien fan to remember Aulë the Maker, whose creations were imbued with life but not by his hands, or Rabbi Loew’s Golem who goes on a rampage and must be deactivated by means of the word carved on its forehead; in some versions of the legend the Golem was even afraid to die, pleaded with the rabbi for its life. Why, if it had no soul?

So what becomes of a warforged when the war for which it was made has ended? All kinds of new stories and morality plays are there for the taking—now, a warforged Player Character can just have fun and be a glorified, armor-plated, sword-wielding Pinocchio going on adventures, defeating monsters and winning glory and treasure, or it can be a philosopher-hero trying to figure out what it is and how it fits into the world. Or it can be both! In one Eberron game I ran, Adamant was the name of one player’s warforged paladin, and he was the party’s moral compass; despite Adamant’s strength and increasing holy power, his player did an excellent job making him fumble through social mores and never quite knew how to stand without looking like a machine of war. He was fond of children and at one point fell in love, as much as a warforged could, with a wood-skinned dryad.

Now, this is not just a pitch for Eberron, I promise! (Though I feel no regret in pushing anyone to discover that campaign setting.) I’m just trying to demonstrate how elements of myth have evolved through our present entertainment. Obviously, lots of movies, TV shows, and books have been exploring similar concepts with robots and AI for decades. Most of those have their roots in Frankenstein, Prometheus, or Talos—that is, in beings who are “made and not born.” I recently pestered Keith Baker, the game designer who invented the Eberron setting about just this. I asked him what exactly was the origin of the warforged? What was their chief inspiration? He named two: the Jewish Golem and Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? No surprises there.

I, too, absolutely borrowed themes from the Golem and from Frankenstein in my own Eberron novel years ago. On the surface, the book is a murder mystery set in a gothic, magic-infused city, but beneath that I explored the complex relationship between one unusual warforged and his creator. I wanted to ask new hypotheticals. Like: suppose that before Victor Frankenstein even had a chance to reject his highly intelligent creation he fell into a coma, and the creature—who had only ever known the laboratory—tried to save him, no matter the moral cost? Except, you know, with some dungeons & some dragons thrown in. (And halflings and kobolds.)

Obviously, myths are revisited in more than just books, TV, and movies. There is music—so much great music—which explores the ever-morphing ideas of the past. I’ve always been inspired by music, and that was before I learned how Tolkien positioned music itself so prominently in his world. Which made it all the cooler. Well, here are just two (of a thousand) examples of myths remade in modern music, which happen to take pages from the same source. Earlier I named Apollo and Dionysus, who are sons of Zeus, the gods of wine and prophecy, respectively. And hey, both are gods of music.

Now take the duo known as Dead Can Dance, which started as a Neoclassical dark wave band that became more difficult to classify over time. Anyway, they are two people, musicians Brendan Perry and Lisa Gerrard, and their whole discography is infused with exotic and mythological explorations, some more obvious than others, like their album Into the Labyrinth. (Some of you may know Lisa Gerrard from her voice on The Gladiator soundtrack, but I assure you there’s so much more of her work to be discovered.)

Well, their last album was inspired by the literary and philosophical concepts in Friedrich Nietzsche’s book The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music. That is, in the Apollonian and Dionysian paradox—logic and reason vs. impulse and emotion, or more simply: the heart vs. the mind. This was a dichotomy popularized by Nietzsche but it preceded even him in the great mythic telephone game. Myth is remade and manifests into philosophy. Now, the Greeks themselves didn’t necessarily see Apollo and Dionysus as opposites or rivals in this way. Again, myths change in the telling and are reimagined. Gods become metaphors and symbols, representing parts of ourselves.

All right, now take the band Rush and its drummer/lyricist, Neil Peart (R.I.P.). In 1977, Peart reimagined this same mytho-philosophical debate in the Rush opus “Hemispheres.” Within, the two gods, Apollo and Dionysus, each offer their particular divine skillsets to the mortal world. Apollo, being the god of reason, brings “truth and understanding / Wit and wisdom fair / Precious gifts beyond compare.” Under his guidance, mortals “build their cities and converse among the wise.” Then one day the people feel empty; they’ve lost all desires; they’re missing something. So they turn to Dionysus, the god of feeling. He brings “love to give [them] solace / In the darkness of the night / In the heart’s eternal light.” He tells them to throw off the “chains of reason.” They comply, abandoning the cities, and live under the stars; they sing and rejoice. But when winter comes, they’re unprepared, facing wolves and starvation for having abandoned Apollo’s more sensible gifts. After a whole wonderfully prog-rock operatic struggle and the arrival of an unexpected, unlooked for—and dare I say eucatastrophic?—newcomer, Cygnus, the God of Balance, the people learn that there must be an equilibrium between the two states of being. The two halves of the human brain, the hemispheres of love and reason, must unite into a “single, perfect sphere.” Another sweet myth remade for the modern age.

I for one think of Rush first when I think of Dionysus and Apollo, not so much the wine, indulgence, prophecy, and chariots. The Greeks who originally held festivals in the name of Dionysus or made sacrifices to Apollo probably didn’t have angular time signatures, crunchy guitars, and squirrelly rock vocals in mind.

And finally, visual art in all its forms has always taken up the mythological torch, invoking and remaking with new purpose. Sometimes just used as a metaphor, and sometimes transforming. Like: long ago I noticed that the crest of West Point, where I lived many years as a kid, includes the helmet of the goddess Athena, since she represents the ultimate soldier scholar. Wisdom in battle.

But there is one final and more significant example I’d like to bring up.

It’s a stunning sculpture that I’m sure some or most of you have seen (and maybe shared) on social media a while back. It was made in 2008 but got renewed attention during the rise of the #MeToo movement only a few years ago: “Medusa With the Head of Perseus” by Argentine artist Luciano Garbati. Although it was seen by many as a symbol of righteous feminine anger, the artist himself had actually made it ten years earlier and had simply meant to reimagine the story of Perseus and Medusa from her point of view. To depict the woman behind the monster.

This piece of art isn’t a snub, just a shift in perspective. In Garbati’s remade myth, Medusa is victorious against her would-be slayer. I for one am especially transfixed by her face. Seen from some distance, she looks defiant, resolute. More specifically, she does not appear smug. She is victorious, yes, but not gloating. She did what she had to do, even though Perseus was just one of the many who came seeking her death.

Seen up close, or at least from the proper angle, Medusa seems to be almost mournful. It was not her desire to kill; she did not make herself what she is. However you interpret the myth, Garbati’s work is striking.

Now, the artist was fine with #MeToo activism sharing his work for new purpose. Medusa’s tragic story lies behind it, of course, but Garbati had been particularly inspired by Benvenuto Cellini’s well-known “Perseus With the Head of Medusa,” a sixteenth-century sculpture which also invoked the famous myth but had, in its time, actually been commissioned as a political message. Heroic Perseus represented the wealthy, powerful banking family—the Medici—”saving” the city of Florence, while the slain Medusa represented “the Republican experiment” it had defeated.

Does that message live on to anyone looking at Cellini’s sculpture today? In the end, is it mythology, art, or politics? Maybe all three, but the history is only there for those who look into it. Actor/director Charlie Chaplin, when he first saw the Cellini’s sculpture there in Piazza della Signoria were it sits, later said of it:

Perseus, holding up the head of Medusa with her pathetic body twisted at his feet, is the epitome of sadness. It made me think of Oscar Wilde’s mystical verse, “Yet each man kills the thing he loves.”

Where, in all of that, is the original myth of Medusa? It almost doesn’t matter.

Myths, like art, are tools for our use. We are their inheritors. And just as technology has advanced exponentially since the Industrial Revolution, so too has the pace of our mythological consumption and reinvention. Mass media has snowballed everything in our lives, and somewhere in the din of politics and social turmoil and everything else we’ve been pelted with there are old metaphoric narratives of relevance worth revisiting again and again. And not just revisiting. Redoing, maybe for the betterment of ourselves and others. Write a book, write an essay, make a movie, roll some dice, and tell your own story using any of the “truths” of old, of what it means to be human.

As Tolkien says, certain truths and motives “must always reappear.”

Finally, in the spirit of remaking myths, I asked my friend Russell Trakhtenberg, a senior designer in the Tor art department, if he would throw the following sketch together. This is to right a great wrong as far back as 1977, first called out in John Gardner’s review of The Silmarillion. Gardner had lamented that while numerous characters in that book “have interest,” “none of them smokes a pipe” and “none wears a vest.”

Well, then, I give you…

Jeff LaSala brought his family to Mythmoot, where on costume night his wife and son became hobbits. He remains grateful to Signum University for the experience. As always, he is responsible for The Silmarillion Primer, the Deep Delvings series, and a few other assorted articles on this site. Tolkien nerdom aside, Jeff wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and works in production for Macmillan and Tor Books. He is sometimes on Twitter.

One quick note. I’ve been wanting to share the unofficial poster boy of the “remaking myth” them as it exists in MY head, which was this delightful illustration, “Crafty Minotaur” by jk-bees. I was unable to make contact with her to get permission to share it. Even so, I want to world to know about it. I order a t-shirt and would get more if I could. I hope the money goes back to her.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BrGvrg8BN9q/

And if I had one wish, and could impose upon anyone reading this one song they must listen to, it wouldn’t actually be Dead Can Dance or Rush (although they would be missing out). It would “Time Without End” by Bel Canto. No complex lyrics here, just a mythical dreamlike quality so fitting for this topic. And the reference to a minotaur doesn’t hurt.

Tldr; FANFIC IS VALID, Y’ALL!

Thank you so very much for showing me that sculpture. It is a delight in oh so many myriad of ways.

I am left remembering the glorious (and hilarious) Silmarillion in 1000 words:

I believe this link on Archive.org is to the original author’s page.

camwyn: And now the ENTIRE THING. (archive.org)

@3: thank you for the link! I can’t believe I’ve never seen that one before, that’s hilarious.

Thanks Jeff LaSala. Have loved all your articles here related to Tolkien and still appreciate that you turned me on to the guys at the Prancing Pony Podcast, which I still listen to. Now I’m working on some of the stuff from the Tolkien professor (other minds and hands and the Silmfilm project) on my long drives and loving that as well.

Wish I could’ve been at Mythmoot (I’ll get there one of these days) but being able to read your keynote was great.

Thanks for the kind words, Kent. SO glad anything I’ve said has sent more folks to the PPP and the Tolkien Professor. You will never want for thoughtful content if you’re following them. Other Minds and Hands has been great, yeah.

Always interesting to read your articles. I love the crafty Minotaur!

I was reading this and thinking “he hasn’t mentioned Rush yet”, and then we get the reference to Rush!

@7 Thanks! The Crafty Minotaur is my spirit (mythological) animal. As the kids say.

Yes, normally I find some little bit of applicability when it comes to Rush. But this time a full-on I explanation was just staring me in the face. And I didn’t even have time to bring up the Rush opus “The Fountain of Lamneth,” which its references to Bacchus and Panacea and Odysseus . . .

Excellent read, lots of great insights into the cycle of story. Will be consulting this again, gives me a great deal to think about. I learned a lot!

Thanks for posting this. My how you must have been intimidated, yet you seem to have held your own marvelously. How I love the crafty (multiple meanings) Minotaur!

“Hold my own” might be applicable among rivals. But these folks were great and put me at ease. Couldn’t have asked for nicer people. It all worked out despite the months of nervous prep that preceded it. I’m not a natural speaker, so I had to work at it a bit, and in the end it only worked out well because I got to straight-up read my paper and run some slides (which used a lot of the visuals above).

I had to set some time to read this but what a fun talk – this is one of my favorite topics to geek out about, really.

Your musings on the warforged actually had me thinking about something else – the use of clone troopers in Star Wars, and what happens to them afterwards. What is the morality of using them? What rights/personhood do they have? (I think Karen Traviss’s books do a lot witht his concept, and of course later on stuff like The Clone Wars/The Bad Batch continue to explore this idea).

@2 – I was in fact thinking of fanfic as well. Not just in how we tell or re-tell tales (and what we decide to emphasize, what is important, what we distill from them) but how individuals then take those elements and create their own tales.

Oh man, the Silmarillion in 1000 words brings back SO many college memories. SHINY.