For some of us readers, this is Kelly Link Week. The publication of her new collection, White Cat, Black Dog, is cause for great celebration. That celebration began earlier this month with a profile in Vulture that included endearing details such as the names of Link’s chickens and a short history of her publishing career.

But what I got stuck on—hung up on, in the most enjoyable way—is a bit about stories and novels. “The novel hardens as you go on,” she says to the interviewer. “At a certain point the ambitions, even the shape, begin to feel inevitable. The short story stays fluid.”

Link is talking about writing, but my reading brain bit down on this and wouldn’t let go. What does inevitability—hardness—feel like in a novel, and where does fluidity lie? Can a novel stay fluid? And how do genre and style play into it?

This is all very subjective and maybe slightly esoteric as a result; my fluid novel won’t necessarily be yours, not any more than a story that feels inevitable to you is necessarily the same for me. As readers, these things are, at least in part, products of what we bring to the page. I’ve read plenty of books that felt inevitable simply because of the sheer number of stories I’d already read in the same vein (YA dystopias of the 2000s, I am looking at you). But I like to think that every one of those books was also discovered by a reader who had never seen anything like it.

Some stories are meant to feel inevitable—that isn’t a bad thing. There’s the sense that it couldn’t possibly have turned out any other way; the sense of dread as you feel a tragic ending approaching; the sense of clockwork in a taut thriller, of carefully plotted strands in a story about prophecy. That kind of narrative inevitability can be fascinating, compelling, propulsive. I read most of the Expanse novels in huge gulps because once the pieces start moving, they slide you right into a narrative that pulls. It’s a narrative rich with character, and world-building, and scale and hope. But I don’t know that I would call it fluid. It knows where the edges are and fills them in brilliantly.

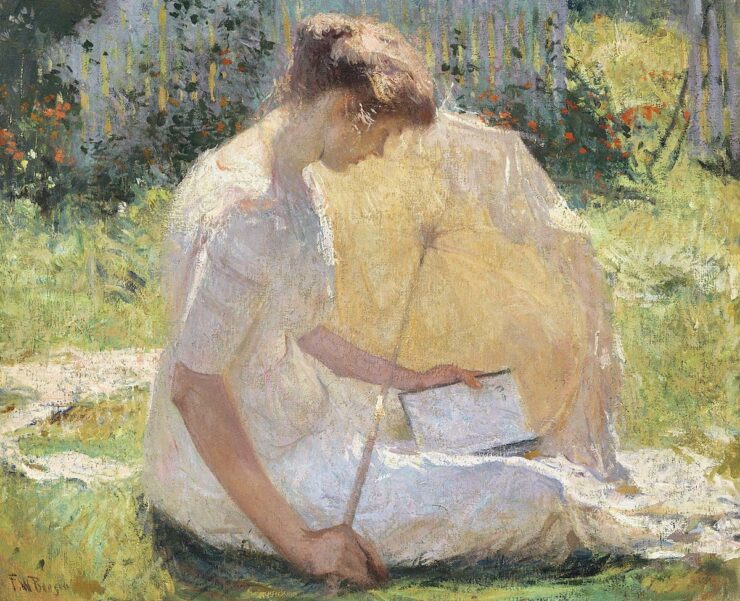

What I think of, when I think of the idea of fluidity and stories, is an unwillingness to be pinned down. An elusiveness. You can’t attach a tidy moral to a fluid story, or easily sum up what it was “about.” What you take away from it is likely more image, feeling, exchange than plot or drama, though those may be present.

For me, fluidness has to leave something unsaid, undefined, un-detailed. The worldbuilding is atmospheric, not precise. A fluid story does not, I think, come with a map. (Unless it’s a very peculiar map, like the ones in Catherynne M. Valente’s Palimpsest.) Fluidness in a novel looks, maybe, like the work of Helen Oyeyemi, like the not-quite-fairytales she spins in Gingerbread and Boy, Snow, Bird, like the house in White is for Witching, which I remember entirely as an atmosphere—one I both long to revisit and feel inexplicably anxious about.

There are stories that call for fluidness and stories that don’t, the same way there are stories that call for different settings, different styles, different vibes. An interesting flurry of things have been said this week about style and its place in the literary landscape—people discussing a frequent question about whether some writers are just better at plot and some better at style; whether “invisible prose” exists; whether there are two kinds of readers, each wanting one thing or the other, style or story, or some other binary that is only one axis along which we read.

Do any readers really only ever want one thing? Does any book really only do one thing? Does style belong in SFF? And what does that question really mean?

To some degree I’m with Lincoln Michel, whose piece on “invisible prose” I linked above; I don’t really think any prose is invisible. Still, I also understand what readers mean when they say that: They mean the words are under the story, for lack of a better way to put it. You notice what’s happening, rather than how the author describes it happening. Michel’s point is that a story is its prose; you can’t take them apart. But I like Max Gladstone’s way of putting it; he proposes an “additional tension: between texture and aerodynamics.”

This clicked immediately into my brain—yes, exactly. A texture you slow down to consider and feel, or an aerodynamic style (but it is a style!) that keeps you moving smoothly along. One is not without the qualities of the other, but the ratio changes. The ratio changes in everything, book to book, even page to page.

Fluidity has texture. Fluidity makes you stop and feel the edges, the seams, the velvet underpinnings and the granite backdrops. And I think my colleague Christina Orlando got at something about fluidity and hardness when they tweeted:

this is maybe controversial but theres a BIG divide in genre fiction particularly between plot-forward writing and prose-forward writing. most sff readers prefer the former, most top sff writers are the former. lyrical sff is often called literary. there are few who can do both https://t.co/jXsgKMkGL7

— christina orlando 🌙 (@cxorlando) March 24, 2023

The most nail-on-the-head part of this observation, to me, is the bit about how the prose-forward SFF writers are often considered literary, or elevated, in a different way. Why do some clearly speculative stories get published by literary imprints, shelved in general fiction, treated as if they are not SFF stories at all? It’s not always because they are prose-forward, but it’s part of it. Kelly Link’s gorgeous stories belong to SFF readers, but they belong to general readers, too; her books aren’t always in the SFF section, and her last collection, Get in Trouble, was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize. Karen Russell’s Swamplandia and Eowyn Ivey’s The Snow Child were also Pulitzer finalists; both, I think, could be called fluid—and be claimed by speculative readers as well as the mainstream.

Boundaries are porous things. (Where do we put Victor LaValle’s The Changeling? The recent novels of Emily St. John Mandel?) None of this is writ in stone; very few writers do just one thing. But there is something in here about how books are received, if not written—about what different readers want and how those desires are regarded; about what is viewed as “good” writing and what people take for granted; and about how writers are somehow shelved into sections or classifications that don’t suit them.

I think what I want from all of this is more fluidity across the board—more lyrical SFF novels, more willingness to ignore the lines, erase the maps, step off the edges of the known world. Can we be more fluid readers? What does that look like?

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.