Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “Pickman’s Model,” written in September 1926 and first published in the October 1927 issue of Weird Tales. You can read it here.

Spoilers ahead.

“There was one thing called “The Lesson”—heaven pity me, that I ever saw it! Listen—can you fancy a squatting circle of nameless dog-like things in a churchyard teaching a small child how to feed like themselves? The price of a changeling, I suppose—you know the old myth about how the weird people leave their spawn in cradles in exchange for the human babes they steal. Pickman was shewing what happens to those stolen babes—how they grow up—and then I began to see a hideous relationship in the faces of the human and non-human figures.”

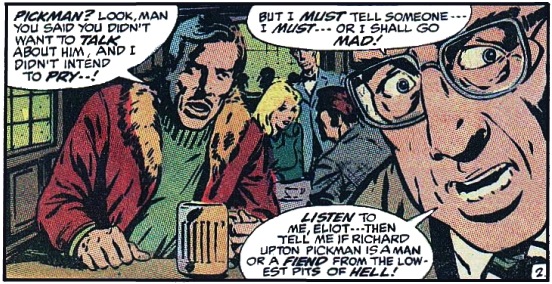

Summary: Our narrator Thurber, meeting his friend Eliot for the first time in a year, explains his sudden phobia for the Boston subway and all things underground. It’s not crazy—he has good reason to be anxious, and to have dropped their mutual acquaintance, the artist Richard Upton Pickman, and yes, the two things are related.

Thurber didn’t drop Pickman because of his morbid paintings, as did other art club members. Nor did he hold with an amateur pathologist’s idea that Pickman was sliding down the evolutionary scale, perhaps due to abnormal diet. No, even now, Thurber calls Pickman the greatest painter Boston ever produced—an uncanny master of that “actual anatomy of the terrible and physiology of fear” which mark the true artist of the weird.

Pickman’s disappeared, and Thurber hasn’t informed the police of a North End house the artist rented under an assumed name. He’s sure he could never find the place again, nor would he try, even in broad daylight.

Thurber became Pickman’s eager disciple while planning a monograph on weird art. He viewed work that would have gotten Pickman kicked out of the club and listened to theories that would have landed Pickman in a sanitarium. Having thus earned Pickman’s trust, he’s invited to the artist’s secret studio in Boston’s North End.

The North End is the place for a really courageous artist, Pickman contends. So what if it’s become a slum swarming with “foreigners?” It’s old enough to harbor generations of ghosts. Houses still stand that witnessed the days of pirates and smugglers and privateers, people who dug a whole network of tunnels to escape their Puritan persecutors, people knew how to “enlarge the bounds of life”! Oh, and there were witches, too. Like Pickman’s four-times-great-grandmother, who was hanged during the Salem panic.

Pickman leads Thurber into the oldest and dirtiest alleys he’s ever encountered. Thurber’s amazed to see houses from before Cotton Mather’s time, even archaic PRE-GAMBREL rooflines supposedly extinct in Boston. The artist ushers Thurber inside and into a room hung with paintings set in Puritan times. Though there’s nothing outré in their backgrounds, the figures—always Pickman’s forte—oppress Thurber with a sense of loathsomeness and “moral fetor.” They’re chiefly bipedal(ish) monstrosities of canine cast and rubbery texture, munching on and fighting over “charnel booty.”. The worst paintings imply the ghoulish beasts are related to humans, perhaps descended from them, and that they exchange their young for babies, thus infiltrating human society. One shows ghouls teaching a human child to feed as they do. Another shows a pious Puritan family in which the expression of one son reflects “the mockery of the pit.” This awful figure, ironically, resembles Pickman himself.

Now, Eliot saw enough of Thurber during WWI to know he’s no baby. But when Pickman leads him into a room of paintings set in contemporary times, he reels and screams. Bad enough to imagine ghouls overrunning the world of our ancestors; it’s too much to picture them in the modern world! There’s a depiction of a subway accident, in which ghouls attack people on the platform. There’s a cross-section of Beacon Hill, through which ghouls burrow like ants. Ghouls lurk in basements. They sport in modern graveyards. Most shockingly, somehow, they crowd into a tomb, laughing over a Boston guidebook that declares “Holmes, Lowell and Longfellow lie buried in Mount Auburn.”

From this hellish gallery, Pickman and Thurber descend into the cellar. At the bottom of the stairs is an ancient well covered with a wooden disc—yes, once an entrance into that labyrinth of tunnels Pickman mentioned. They move on to a gas-lit studio. Unfinished paintings show penciled guidelines that speak to Pickman’s painstaking concern for perspective and proportion—he’s a realist, after all, no romanticist. A camera outfit attracts Thurber’s attention. Pickman says he often works from photos. You know, for his backgrounds.

When Pickman unveils a huge canvas, Thurber screams a second time. No mortal unsold to the Fiend could have depicted the ghoul that gnaws a corpse’s head like a child nibbling candy! Not with such horrific realism, as if the thing breathed. Conquering hysterical laughter, Thurber turns his attention to a curled photograph pinned to the canvas. He reaches to smooth it and see what background the terrible masterpiece will boast. But just then Pickman draws a revolver and motions for silence. He goes into the cellar, closes the studio door. Thurber stands paralyzed, listening to scurrying and a groping, furtive clatter of—wood on brick. Pickman shouts in gibberish, then fires six shots in the air, a warning. Squeals, thud of wood on brick, well cover back over well!

Returning, Pickman says the well’s infested with rats. Thurber’s echoing scream must have roused them. Oh well, they add to the atmosphere of the place.

Pickman leads Thurber back out of the ancient alleys, and they part. Thurber never speaks to the artist again. Not because of what he saw in the North End house. Because of what he saw the next morning, when he pulled from his pocket that photo from the huge canvas, which he must have convulsively stowed there in his fright over the rat-incident.

It shows no background except the wall of Pickman’s cellar studio. Against that stands the monster he was painting. His model, photographed from life.

What’s Cyclopean: Nothing—but on the architecture front we do get that pre-gambrel roof-line. Somewhere in the warrens below that roof-line is an “antediluvian” door. I do not think that word means what you think it means.

The Degenerate Dutch: Pickman boasts that not three Nordic men have set foot in his iffy neighborhood—as if that makes him some sort of daring explorer in the mean streets of Boston. But perhaps we’ll let that pass: he’s a jerk who likes shocking people, and “to boldly go where lots of people of other races have already been” isn’t particularly shocking.

Mythos Making: Pickman will make an appearance in “Dreamquest of Unknown Kadath”—see Anne’s commentary. Eliot and Upton are both familiar names, though common enough in the area that no close relation need be implied—though one does wonder whether the Upton who killed Ephraim Waite was familiar with these paintings, which seem of a kind with Derby’s writing.

Libronomicon: Thurber goes on about his favorite fantastical painters: Fuseli, Dore, Sime, and Angarola. Clark Ashton Smith is also listed as a painter of some note, whose trans-Saturnian landscapes and lunar fungi can freeze the blood (it’s cold on the moon). The books all come from Pickman’s rants: he’s dismissive of Mather’s Magnalia and Wonders of the Invisible World.

Madness Takes Its Toll: More carefully observed psychology here than in some of Lovecraft’s other stories—PTSD and phobia for a start, and Pickman has… what, by modern standards? Antisocial personality disorder, narcissistic p.d., something on that spectrum? Or maybe he’s just a changeling.

Anne’s Commentary

You know what I want for Christmas? Or tomorrow, via interdimensional overnight delivery? A great big gorgeous coffee-table book of Richard Upton Pickman’s paintings and sketches. Especially those from his North End period. I believe he published this, post-ghoulishly, with the Black Kitten Press of Ulthar.

Lovecraft wrote this story shortly after “Cool Air,” with which it shares a basic structure: First-person narrator explaining a phobia to a second-person auditor. But while “Cool Air” has no definite auditor and the tone of a carefully considered written account, “Pickman’s Model” has a specific if vague auditor (Thurber’s friend Eliot) and a truly conversational tone, full of colloquialisms and slang. Among all Lovecraft’s stories, it arguably has the most immediate feel, complete with a memory-fueled emotional arc that rises to near-hysteria. Poor Thurber. I don’t think he needed that late-night coffee. Xanax might do him more good.

“Model” is also product of a period when Lovecraft was working on his monograph, Supernatural Horror in Literature. It’s natural that it should continue—and refine—the artistic credo begun three years before in “The Unnamable.” Pickman would agree with Carter that “a mind can find its greatest pleasure in escapes from the daily treadmill,” but I don’t think he’d hold with the notion that something could be so “infamous a nebulosity” as to be indescribable. Pickman’s own terrors are the opposite of nebulous, only too material. Why, the light of our world doesn’t even shy from them—ghouls photograph very nicely, thank you, and the artist who can do them justice must devote attention to perspective, proportion and clinical detail. Tellingly, one more piece comes from the fruitful year of 1926: “The Call of Cthulhu,” in which Lovecraft begins in earnest to create his own “stable, mechanistic and well-established horror-world.”

Can we say, then, that “Model” is a link between Lovecraft’s “Dunsanian” tales and his Cthulhu Mythos? The Dreamlands connection is clear, for it’s Pickman himself, who will appear in 1927’s Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath as a fully realized and cheerful ghoul, gibbering and gnawing with the best of them. I’d contend that the North End studio stands within an interzone between the waking and dreaming worlds, as Kingsport of the mile-high cliffs may, and also the Rue d’Auseil. After all, those alleys hold houses that supposedly no longer stand in Boston. And Thurber’s sure he could never find his way back to the neighborhood, just as our friend back in France could never again find the Rue.

On the Mythos end of the connection, we again have Pickman himself, at once a seeker of the weird and an unflinching, “almost scientific” realist. He has seen what he paints—it’s the truth of the worlds, no fantasy, however much the majority of people might want to run from and condemn it. Thurber, though a screamer, does show some courage in his attitude toward the North End jaunt—he’s the rare Lovecraft protagonist who doesn’t cling to the comfort of dream and/or insanity as explanations for his ordeal. He’s not crazy, even if he is lucky to be sane, and he has plenty of reason for his phobias.

Of course some (like Eliot?) could say Thurber’s very conviction is proof of insanity. And wouldn’t the ghouls just laugh and laugh about that?

On the psychosexual front, it’s interesting that Lovecraft does not want to go there with humans and ghouls. Things will be different when we get to Innsmouth a few years later; he will have worked himself to the sticking point and acknowledged that the reason for the infamous Look is interbreeding between Deep Ones and humans. In “Model,” gradations from man to ghoul (practically a monkey-to-Homo sapiens parade) are called an evolution. If Thurber’s intuition is correct, that ghouls develop from men, then is it a reverse evolution, a degradation? Or are ghouls “superior,” winners by virtue of that cruel biological law we read about in “Red Hook”?

Anyhow, ghouls and humans do not have sex in “Pickman’s Model: The Original.” They intersect, neatly, via the folklore-approved method of changelings—ghoul offspring exchanged for human babies, which ghouls snatch from cradles, those rocking surrogate wombs they then fill with their own spawn. “Pickman’s Model: The Night Gallery Episode” is less squeamishly symbolic. It gets rid of boring old Thurber and gives Pickman a charming female student, who falls in love with him, natch. No changelings here, just a big virile ghoul who tries to bear the student off to his burrow-boudoir. Pickman interferes, only to be borne off himself. Hmm. Bisexual ghouls?

Looking outside, I see more snow arriving, not the interdimensional mail person. When’s my Pickman book going to arrive? I hope I don’t have to dream my way to Ulthar for it. Although it is always cool to hang with the cats.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

We’ve discussed, in an earlier comment thread, whether Lovecraft’s shocking endings are really meant to be shocking. Chalk this one up as strong evidence against: the ending is telegraphed in the title. The first time Thurber shudders over the lifelike faces in Pickman’s ghoulish portraits, it doesn’t take a genre savvy genius to figure that he might be drawing from, I don’t know, a model? Instead, this one is all about the psychology.

And what interesting psychology! Thurber mentions, to his friend Eliot, their shared experiences “in France” as proof of his usual unflappability. So we’ve got a World War I vet here. That painting of the ghouls tearing down Boston—he’s seen cities destroyed, he knows that horror. But this, the place he’s living now, is supposed to be safe. Boston didn’t get invaded during the war, probably hasn’t been attacked within his lifetime. And now he learns, not that there are terrible, uncaring forces in the world—he knew that already—but that they’re on his home soil, tunneling under his feet, ready to come out and devour every semblance of safety that remains.

No wonder he drops Pickman. I’d have done a damn sight more than that—but it’s 1926, and it’ll be decades yet before horror is something you talk about openly, even when its dangers are all too real.

I’m starting to notice a taxonomy of “madness” in these stories. First we have the most generic sort of story-convenient madness—more poetic than detailed, likely to make people run wild, and not much like any actual mental condition. Sometimes, as in “Call of Cthulhu,” it’s got a direct eldritch cause; other times it’s less explicable. Then we have the madness that isn’t—for example Peaslee’s fervent hope, even while asserting normalcy, that his alien memories are mere delusion. (Actually, Lovecraft’s narrators seem to wish for madness more often than they find it.) And finally, we have stories like this one (and “Dagon,” and arguably the Randolph Carter sequence): relatively well-observed PTSD and trauma reactions of the sort that were ubiquitous in soldiers returning from the first World War. Ubiquitous, and as far as I understand it, rarely discussed. One suspects a good portion of Lovecraft’s appeal, at the time, was in offering a way to talk about the terrible revelations that no one cared to acknowledge.

This also explains why he seemed, when I started reading his stuff, to write so well about the Cold War as well. Really, we’ve been recapitulating variations on an eldritch theme for about a century now.

A friend of mine, a few years younger than me, went on a cross-country road trip—and one night camped out at the edge of a barbed-wire-fenced field with big concrete cylinders. ICBM silos. He thought it was an interesting anecdote, and couldn’t understand why I shuddered. I’d rather sleep over an open ghoul pit.

Or maybe it’s the same thing. You know the horror is down there, but it’s dangerous to pay it too much attention. Speak too loudly, let your fear show—and it just might wake up and come out, eager to devour the world.

Next week, architectural horror of the gambrel variety in “The Shunned House.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.

A likeable story: digressions on art and denunciations of Cotton Mather aside, “Pickman’s Model” leads up well to a great final line. It’s also a good story starter for latter-day Lovecraftian fiction such as, say, “The Madonna of the Abattoir”…

Weird Tales: October 1927 first, along with Robert E. Howard’s “The Ride of Falume”, then reprinted in November 1936, with Robert E. Howard “Black Hound of Death” and Robert Bloch’s “The Dark Demon”. It was also reprinted in 1929 in the anthology By Daylight Only.

I have to say it: when you have a narrator named Thurber, in an early 20th century setting, I automatically think of: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Thurber

Anne M. Pillsworth’s copy of Photographs from Life: The Very Best of Richard Upton Pickman: will arrive today at 34:97 pm. A signature in blood is required for this parcel.

This is probably one of HPL’s best stories. The narrative tone works very well, and the late reveal for once fits. There isn’t a long denoument between climax and reveal and, more to the point, it makes more sense in a “spoken” narrative than in one “written down”.

Two things really stood out to me this time. The first is Lovecraft’s relationship with the visual arts. He does have a tendency to throw around the names of painters of the weird. That could be seen as authorial laziness; saying “like a scene from Doré” is a lot shorter than and easier than trying to describe such a scene. He does seem to have at least tried his hand at sketches. There’s the famous drawing of Cthulhu and I believe he occasionally added the odd drawing or two in some of his letters. In any case, there’s probably a place for some scholarship in the area.

The other thing that jumped out at me was all the drinking. Thurber makes it pretty clear that it’s booze, since he finally backs off to a coffee at the end of the evening. There’s also a waiter or some sort of servant bringing the decanter. But we’re also right in the middle of Prohibition. I suppose it’s just a narrative device to show how shattered Thurber’s nerves are, but it really stood out to me.

This is among my favorite Lovecraft stories, and I believe that it displays his skill in the art of the glance. We’re meant to spend it going Uh, why is Thurber so upset? So Pickman paints gruesomely detailed pictures, has a spooky studio, and seems to be getting a bit weird. What’s so bad about that? Then the photograph is revealed at the very end, one line implying everything — that these creatures are real and his horrific visions of their conquests are possible. Genre-savvy readers nowadays may beat him to the punch line, and it didn’t exactly shock me, but I found it a most satisfying denoument.

Also, I categorically love changeling stories and greatly enjoyed that portion of this tale.

The excellent anthology Lovecraft’s Monsters includes a lovely little tale of romantic attraction between a male ghoul and a part-Deep-one Innsmouth girl, by Caitlin R. Kiernan.

Regarding diagnoses of various individuals (Pickman, here). (I’m a psychologist; the type that works with mental disorders). I haven’t read the story in a while, but I’m not sure that Pickman’s behavior is actually diagnostic. Many artists do have some kind of narcissism like that, but I don’t know quite what to add to that. I don’t know what label he would have, if anything, though he has apparently come to the conclusion that trading babies is okay. Admittedly, giant red flag. But he’s also apparently not psychotic (assuming that ghouls are real).

Thurber, though, has kind of lost it. Having experienced one prolonged trauma (WWI) would like as not make him more vulnerable to the next.

“And now he learns, not that there are terrible, uncaring forces in the world—he knew that already—but that they’re on his home soil, tunneling under his feet, ready to come out and devour every semblance of safety that remains.”

You’ve just captured the experience that a lot of people carry after a PTSD-inducing trauma. It’s certainly common among people who have survived combat tours and then returned to this country. Many, unfortunately, don’t even need the evidence of ghouls to make that assumption.

This does suggest an interesting idea regarding something about a psychological breakdown of Lovecraft’s characters (which may or may not have been done to my knowledge), as opposed to a breakdown of Lovecraft (done all over, to great effect).

Some links:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Fuseli

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustave_Dor%C3%A9

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidney_Sime

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Goya

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Angarola

http://www.eldritchdark.com/galleries/by-cas/all/a/1

http://scribol.com/travel/paris-evolving-under-the-gaze-of-notre-dames-gargoyles

http://www.pbase.com/image/22301471

http://www.hplovecraft.com/life/interest/artists.aspx

Charlie Stross, in the afterword to “The Atrocity Archives”, makes exactly that link between Lovecraft and the Cold War – during the Cold War there really were slumbering forces of unimaginable destruction waiting to be woken by the correct incantation and bring about the end of humanity. It’s just that the correct incantation wasn’t so much “Ph’nglui wagh’nagl Rl’yeh Cthulhu fthagn!”, it was more like “This is SAC headquarters. Authenticate APPLE JACK. Execute SIOP, target package DELTA.”

Schuyler: I too cannot help wondering what that Thurber would have made of the situation. I really want a Thurber-cartoon illustrated edition of Lovecraft. “All Right, Have It Your Way; You Heard An Inhuman Unearthly Shriek”.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 2: My distinct impression was that during Prohibition, there was a whole lotta drinking going on. And that for a lot of places, fines and raids were part of the cost of doing business.

I also suspect a lot of writers have visual arts envy. I can’t be the only one who sometimes wants to be able to show *exactly* what’s going on in my head. Or at least, in moments of prosopagnosic frustration, have a head that actually shows me exactly what’s going on.

Autochef @@@@@ 4: Presumably he sometimes feeds his models, as payment for holding still long enough for a photograph. I suppose whether that’s really clinical versus just societally taboo depends on where he gets the meat.

The psychological breakdown process itself seems to be another of Lovecraft’s big obsessions–something I think later authors sometimes miss who try to produce an effect directly in the reader without showing how it works in the character. (But then, I’m a hard reader to horrify directly, so I would say that.) That, and the companion idea that sanity-preserving world-views are merely tissue-thin illusion, and have little room to bend before they break.

a1ay @@@@@ 6: No coincidence–I’m a Cold War baby, and that afterword really helped crystalize the way I thought both about Lovecraft and about my own interpretations thereof. Brilliant stuff.

Ruthanna @6

Well, sure the impression is that everybody was hanging out in speakeasies and drinking bathtub gin, but I wonder how much of that stems from the gangster movies of the 30s and 40s. But I have a hard time seeing HPL being involved in that sort of thing and thus thinking to write about it. Maybe somebody in the Kalem Club “knew a guy”.

As for Pickman paying off his models, I wouldn’t be too surprised to learn that some of the dodgier “models” who worked the Boston art world disappeared from time to time.

Thinking of the Degenerate Dutch, it should be noted that the sketchy neighborhood seems to have been largely Italian. (Pickman’s landlord is a Sicilian.) For all of Pickman’s snobby comments, HPL doesn’t seem to have been too down on the Italians here. It’s a poor and crime-ridden neighborhood, but that almost seems to be poverty-related rather than due to the racial issues in Red Hook, say. It’s certainly a step up from last week.

Also, in the picture heading the post, why is Ernest Hemingway sharing a beer with a highly neurotic Henry Kissinger?

A fun thing to do with this story is to retrace the walk into the North End from the T. There isn’t an elevated or a shuttle to Battery Street anymore, but you can walk from South Station pretty easily. (Or take the Blue Line, but honestly.) The route I have done in the past is to leave South Station and cross Summer Street through the Federal Reserve Plaza Park, then follow Atlantic Avenue for a mile, past a great many new and expensive condos and then Long Wharf and the Aquarium. Wave to Faneuil Hall from across the street, head up through the more commercial wharving, and turn left at Battery before you hit the Coast Guard base. When Battery hits Hanover, turn leftish around the triangular corner and go up Charter Street to Copp’s Hill Burying Ground itself; then either down Snow Hill to Thacher until you reach the original Mama Regina’s Pizzeria, or back along Hull to say hi to the Old North Church. Either way, take Prince Street back to Hanover and end the tour at Mike’s Pastry before reaching back to the T at Haymarket. It’s a very pleasant day’s walk, less than five miles but filled with a range of neighborhoods and sites of historic interest. I have never encountered any pre-gambrel roofs, I’m afraid, not even when I was at the North Bennet Street School and in the North End every day.

Lovecraft had good taste in weird art. I once checked out of the library a copy of Huysman’s La-Bas with a Fuseli cover that turned out to disturb me so much as a cumulative effect that I couldn’t have it in the house. It wasn’t one look that did it, but after a couple of hours the thing was obviously plotting something.

Interesting in a sf kind of way–a parallel species, apparently able to understand human language [reading that guidebook, HPL’s funnniest scene.] Or were they really separate? We read that Pickman’s dad is still around, and has one of the paintings–did Pickman Senior perhaps get up close and personal with a ghouless? Trading babies might be only the start.

Biology–they seem to have different ideas about freshness of meat than we do. Out of several spp. of omnivores I recall, only humans have a lack of tolerance for decayed meat. Different internal microbiota or something. One wonders if this could be fixed, but I suspect the tastebuds would have to be reworked as well…Ghouls would need to have other food sources than humans, dead or alive, just because the latter breed so slowly, but there are lots of animals around even in the city. If all the rats disappear, one might want to be cautious.

The underground sector being filled with their tunnels presents a believability issue–all the removed dirt has to go somewhere. Also, wolves and bears might dig shallow dens but truly fossorial animals tend to be a lot smaller, because there’s a limit to how big a tunnel you can make in dirt, before it collapses. I don’t recall if the ghouls are described as skilled in the art of reinforcing tunnels.

The narrator calls them mephitic, and this is a good point for someone to point out that Mythos fiction in general has a thing about smells. Anything sinister is said to stink awfully instead of just smelling odd. After a while a reader wonders if all these narrators, or authors, are projecting something. High-status groups of people are big on accusing the lower-status ones of smelling bad–compare the number of feminine vs. masculine deodorants. I recall supposedly normal people whose breath would wilt plastic flowers at 20 paces. One need not turn to fiction for horrors.

There is a whiff of protest-too-much in Thurber’s repeating of how brave and tough he usually is, sounding like me as a teen, though his war experiences, which I did not have, give him reason to be upset or triggered no matter how tough he was. Also, Pickman’s going on about the wonderful unrepressed olden days, dumping on those who rejected him, sounds a bit like someone who had never actually had their life threatened by pirates or inquisitors. Of course this is supposed to be someone who is turning into a ghoul or was partway there from the start, but it makes you think about the last [or next] time you hear someone romanticizing the old days like that.

Architecture–some decades back I checked out a book on alleys, which the library no longer has, and it contained part of an old map that revealed that Boston was once just as convoluted as Thurber described. Above ground, anyway.

What’s really amusing is that the Whelan and Palencar covers on my editions of Lovecraft are truly Pickmanesque in their creepy realism. Thurber would have had laundry problems.

I enjoyed the story even though I suspected how it would end. You folks are doing good work in working these stories over.

@9: Ooh, I wish Id tried that when living briefly in Boston to intern at the aquarium.

Rush-That-Speaks@9

As with “The Festival,” Lovecraft’s words memorialize a moment in antiquarian architecture that was about to pass. “Pickman’s” was set in the North End as it was on his first visits, prior to WWI. When he returned several years later, he was annoyed to see most of what he had described had been replaced by the brick tenements we see now.

Anne wrote: “I’d contend that the North End studio stands within an interzone between the waking and dreaming worlds, as Kingsport of the mile-high cliffs may, and also the Rue d’Auseil. After all, those alleys hold houses that supposedly no longer stand in Boston. And Thurber’s sure he could never find his way back to the neighborhood, just as our friend back in France could never again find the Rue.”

Yes, I think so. The rules of nature being a little different would evade the plausibility problem, that Angiportus correctly notes, of the ghouls riddling the earth with tunnels without having to make dirt dumps on the surface, or worry about unshored burrows collapsing (the same issue that we see in “The Lurking Fear,” but there, I think that Lovecraft just hadn’t thought out the real-world issues involved in subterranean delvings).

I’m pretty well convinced that all underground passages in Lovecraft connect to another dimension, possibly the Dreamlands or an offshoot thereof. If you go far enough, you end up in the Underdark, from whence you can fight your way back up into D&D’s pseudo Middle Earth.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 8: I was thinking less bathtub gin and speakeasies, and more… okay, so, I’m very nearly the most chem-free, straight-edge person possible–my prefered choice of mind-altering substance is theobromos. But I know that if you want THC, in the areas where it’s still illegal, you can go to a wild frat party, hang out and have brownies with a couple of old hippies, or track down that guy everyone knows and have a nice relaxing time in the privacy of your own home. If I suddenly decided I wanted some pot, I’m pretty sure I’d be able to get ahold of it inside 12 hours, and I’d have no difficulty writing a character who used it to get their mind off of cosmic horror. This for a substance that was illegal for decades before I was born, rather than the at-the-time-of-the-story relatively recent phenomenon of prohibition.

Shorter argument: even very sheltered writers probably know someone who knows someone, or at least can be pretty willing to write characters who do.

You know what I want for Christmas? Or tomorrow, via interdimensional overnight delivery? A great big gorgeous coffee-table book of Richard Upton Pickman’s paintings and sketches. Especially those from his North End period. I believe he published this, post-ghoulishly, with the Black Kitten Press of Ulthar.

NICE! Would you settle for Hannes Bok?

In “Model,” gradations from man to ghoul (practically a monkey-to-Homo sapiens parade) are called an evolution. If Thurber’s intuition is correct, that ghouls develop from men, then is it a reverse evolution, a degradation?

Years ago, I read an essay (author sadly forgotten) postulating that the transformation from human to ghoul involves an Id-Ego inversion, and the hormonal changes accompanying the change in brain chemistry involved in the flip cause the physical manifestations of “ghouldom”.

For a good pre-Lovecraftian ghoul story, you can’t be Edward Lucas White’s Amina (PDF). You can see Pickman’s “DNA” in that story.

Just as a data point, as a teenager I was completely blindsided by the final line.

I think there’s a structure here that is being overlooked. As the story progresses, Lovecraft cranks up the horror by *bringing the bad thing closer*. He does this in other stories too, but it’s particularly… what’s the word I’m looking for? Step-by-step.

Consider:

— We start by noting that there are a lot of aspersions on Pickman’s sanity and reliability. (He’s nuts, so anything he raves about isn’t real and so isn’t dangerous.)

— Narrator notes that while creepy, Pickman does not actually seem to be insane.

— Tour of studio begins. Narrator emphasizes “fantastic” and “grotesque” nature of paintings. (He may not be nuts, but they’re just paintings.)

— Tour continues. Narrator emphasizes realism of paintings, variations on initial themes, details. Paintings are set in a real-world historical context. (Still just paintings, but clearly they’re part of a complete imagined universe with its own internal consistency.) Connections to the “real world” now, but implied and historical.

— Tour continues. Subjects of paintings now erupt into modern world. (The imagined universe is now colliding with our own.) Connections to the real world are no longer implied, but explicit, and are connected to the current day.

— Incident with rats and gunshots. (Something bad and dangerous is nearby.)

— Final revelation. (It’s all true, Pickman’s imagined universe is completely real.)

It’s a very *structured* story. I think what made it so disturbing to my teenage self was that it’s really about the eruption of the fantastic and horrible into the real, waking world. The slow, step-by-step buildup makes this eruption much more effective when it finally comes.

Doug M.

Two other thoughts. One, at the time that Lovecraft wrote, a photograph was much stronger evidence than it would be today. Photographs required a fair amount of expensive equipment to make — a tripod arrangement like Pickman’s would likely have cost several months’ wages for an everage working man, and then he’d need a darkroom — and then, once made, they were very difficult to change or forge convincingly. Courts universally accepted photographs as the hardest of hard evidence. Meanwhile, costuming, prosthetics and special effects were in their infancy. So “it was a photograph from life” has a punch that it wouldn’t in an era of Photoshop and zombie makeup kits.

Also, note the conceptual leap here: up until now, it’s all been painting. Suddenly it’s a photograph, which is representational like a painting but is critically different.

One difference between Dreamland and Mythos stories is that in the Mythos, characters regularly use modern technology to interact with the uncanny — you can take photographs of the monsters, attempt to shoot, radiate, or pour acid on them (it doesn’t generally work, but you can try) or even run them over with steamboats. The high point of this is probably the protracted analysis that the scientists run on the meteorite in The Colour Out Of Space, but it’s all over the Mythos stuff.

Doug M.

Ruthanna @14

I was thinking about the obvious parallels with cannabis, too. And of course there was a greater tendency to flout the law since alcohol had been a social staple for millennia. But Lovecraft’s outward persona has always seemed so straight-laced, conservative and, dare I say, Puritanical. It just felt odd.

Doug Muir @17

That’s a good point about the hard reality of a photograph. That’s one of the things that made the Cottingley fairies so credible to people (although they look like such obvious fakes today). Photographs played a role in Akeley’s credibility in “Whisperer” too. But I would quibble with the expense of Pickman’s equuipment. The introduction of the Brownie in 1900 drove prices for most equipment downward. Even higher end cameras were coming down in price. And Pickman could probably have picked up a used plate camera fairly cheaply, since film had pretty much won the battle. He may have used his studio as a darkroom when necessary. That’s not really all that costly, just a few chemicals. The instant camera was invented in 1923, but if it was already on the market, it probably was extremely expensive. Maybe Pickman was independently wealthy or his friends were bringing him interesting antiques that he could sell.

@13 In his essay “Lovecraft’s Arkham Country” (reprinted in “Books at Brown 1991-1992 Vols. 38-39), Will Murray notes how Lovecraft’s fictional “geography” is frequently both precise and vague: He will give detailed and vivid descriptions of a particular place, be it Innsmouth or Kingsport, while being rather nebulous about just where these places are located in the “real world.” Although he doesn’t mention it in the essay, it would seem that the North End of Boston in this story fits this pattern: while it was apparently based on a real neighborhood (which was demolished subsequent to the story’s publication) and Thurber’s description of his walk to Pickman’s studio seems highly exact, there are elements that place it outside of the actual Boston that existed at that time.

I think it’s kind of well done how HPL doesn’t use the word “ghoul” a whole lot in this story–just for an undescribed picture mentioned early on, and then later as the story unfolds we start to realize what a ghoul looks like, that that is what these creatures are called.

Humans who want to read more about them might send the library after “Throne of Bones” by Brian McNaughton. Be advised, this is not for anyone with a weak stomach–he gets detailed.

Doug Muir @@@@@ 16&17: Good points, both about the structure (which does parallel several other stories) and the photographs. It’s hard to imagine what would count as equally strong evidence these days–the ease of modern special effects can be jading. The tetragrammapalantir from “Haunter” might do it, or maybe a good satellite image of the ruins in the Australian desert. But photos and dark stones carved with alien iconography can easily be ordered on Etsy.

And yes, it’s telling that the Mythos can usually interact with technology, even when it does confound it. Very different from the way a lot of modern writers handle magic (which the Mythos is always right on the edge of, even with SFnal explanations). I’ve heard some people suggest that working cell phones aren’t really compatible with horror; one suspects Cthulhu would stand up to them just fine. And Nyarlathotep is probably on Twitter, Facebook, Vine, and Instagram.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 18: The Puritans were quite the alcohol drinkers. When I checked my memory on that, Google assured me that the Mayflower carried more beer than water. Then there’s the class aspect: drinking (particular types of alcohol, in particular ways) is pretty central to upper class waspery–and after all, aren’t those pesky laws really for those people over there, the ones who can’t handle it, the ones who get violent and uppity when they drink?

Which is to say, straightlaced, conservative, puritanical people do and did drink a great deal. They just didn’t (and often still don’t) trust other people to do so.

@21 The Puritans had no problems with people drinking alcoholic beverages, just with them drinking to excess. In a place and time when water was frequently unsafe to drink, fermented beverages such as beer and ale were commonly consumed–they were of lighter alcohol content than today, and would most likely have been “flat,” since carbonation would not last long without effectively sealed containers. Hard cider would also have been widely consumed.

There are also plenty of surviving diaries from Puritan clergymen mentioning stopping at at the tavern for whiskey before going to church to perform services.

See PURITANS AT PLAY by Bruce Daniels, which has an excellent chapter on alcoholic beverages in Puritan culture in colonial Massachusetts.

What really struck me when I first read this story as a teenager in California was the achitecture of the North End.We just don’t have those kinds of narrow streets and congested alleys in CA.Naturally, when I moved to the Boston area, one of the first things that I did was go on a tour of the North End.And, yeah, there really is something creepy and claustrophic about those streets.

“You needn’t think I’m crazy, Eliot”: MMM, another dig/reference to/at TS Eliot?There was, after all, the bit in “Charles Dexter Ward,” and Lovecraft did write a pretty good parody of the “The Waste Land,”

“Waste Paper: A Poem of Profound Insignificance”:

http://www.hplovecraft.com/writings/texts/poetry/p228.aspx

Influence On: Robert Barbour Johnson’s “Far Below,”

https://books.google.com/books?id=_LTtvNnkAhsC&pg=PA11&lpg=PA11&dq=far+below+robert+barbour+johnson&source=bl&ots=Qrg4_b3dhv&sig=6gwi9VVW8igNF4eapkw0MKufKN0&hl=en&sa=X&ei=wcEBVbTzK4vvgwS8-YEI&ved=0CCYQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=far%20below%20robert%20barbour%20johnson&f=false

@6″ I really want a Thurber-cartoon illustrated edition of Lovecraft. “All Right, Have It Your Way; You Heard An Inhuman Unearthly Shriek”.”

A Thurber-esque pastiche of Lovecraft sounds pretty nifty to me.After all, we’ve already had Wodehouse meets Lovecraft:

“Scream for Jeeves:A Parody,”

By Peter Cannon

http://www.amazon.com/Scream-Jeeves-Peter-H-Cannon/dp/0940884607

Andf then there was Alan Moore’s “What Ho, Gods of the Abyss!”

http://asylums.insanejournal.com/scans_daily/474960.html

And a kind word for Tom Palmer, normally an inker (and one of my four favorite such), who handled the art chores on this tale. Palmer was a top-notch finisher. He could make Neal Adams look great, but who couldn’t? Palmer could make even Dashing Don Heck’s usual rushed (or perhaps dashed) pencils look enough like Adams to fool the unwary for a few pages. About the only other solo efforts I know for Palmer were, appropriately enough, on Dr. Strange.

(Wallace Wood could also make Heck look good, and probably by a similar process of mostly redrawing his art. When Wood inked over Heck in some early Avengers tales, the faces were pure Wood.)

Excellent column! Am kicking myself for not finding it sooner, but looking forward to working my way through your archives. At the risk of posting a bald-faced advertisement here, i would like to say that plans are laid for a coffee-table art book but that may be a while in coming. In the mean time, closely related products are currently available as of this posting. Interested parties are invited to look me up on deviantArt, and / or stop by The Pickman Conservative on pHaCEbuk for a nosh.

Sam @@@@@ 26: Welcome–glad you’re enjoying the column!