In 2017, at a small SF con in Toronto, I was on a panel where the participants predicted the near-future of humanity. The panelists were two Baby Boomer men, two Millennial women (all four with PhDs) who probably know where to buy cryptocurrency, and me, a non-PhD from Generation X. I sat between these two pairs and was struck by the contrast in opinions. The Boomers saw only doom and gloom in the years ahead, but the Millennials saw many indications of progress and reasons for hope.

I don’t mention the panel’s demographics to be argumentative or to stir up gender or generational divisiveness. It was only one panel. But opinions split starkly along gender and age lines. I was amazed that the two Boomer men—the demographic who are the architects of the world we live in—were really quite scared of the future. I’d love to investigate this split further. I think it’s significant, because in a real, non-mystical way, the future we imagine is the future we get.

This isn’t magical thinking. We create opportunities by imagining possibilities, both for ourselves personally, and for the world in general. I’m not saying we can conjure luck out of thin air, or that applying the power of imagination makes everything simple and easy. But there’s no denying the importance of imagination. The things we imagine fuel our intentions, help us establish behavior patterns that become self-perpetuating, and those patterns generate opportunities.

To repeat: The future we imagine is the future we get. This becomes especially true when whole groups of people share the same dreams.

As the sole Gen Xer on this panel, I was on the side of the Millennials. Most Generation Xers are, and in any case, I will always side with the future.

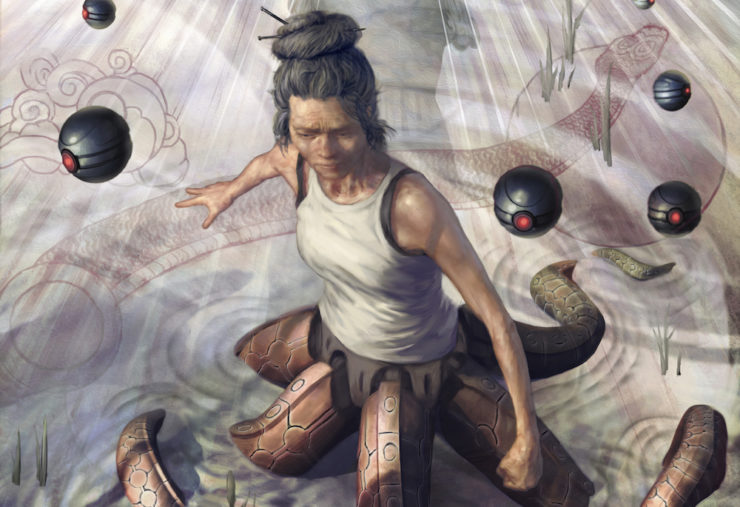

The future I see is complex indeed. Here’s a run down of my vision, which informs my book Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach.

My future is post-scarcity

We already live in a post-scarcity world. We produce enough food to feed everyone on Earth. We produce enough energy to keep all humans safe and warm, and enough clean water to drink. Extreme poverty exists not because we don’t have enough to go around, but because we can’t distribute it. People die of starvation because of political barriers and supply chain problems, not scarcity.

In my future, these supply chain problems are solved, and the political ecosystem acknowledges and values the economic contributions of every human. That may sound utopian, but it’s not, because…

My future is overpopulated

Human economic activity is organized around shared delusions. Sorry—delusions is too strong and prejudiced a word, but collective agreements sounds far too organized. Perhaps dreams is more accurate. In any case, we have agreed that a dollar is something of value that we can trade for other things. The dollar has no value in itself. That’s Economics 101, and it’s nothing we need argue about right now.

Buy the Book

Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach

What I’m trying to get at is this: Since the 1990s, we have agreed that people’s time and attention generates value even when they’re not working. When we open a browser window and Google something, even if it’s as trivial as celebrity gossip or as pointless as ego-surfing, we are adding to Google’s value—even discounting ad revenue. Google is worth billions because we all use it. If nobody used Google, the company would be worthless.

So, human time is worth money even when we’re not on the clock. That’s a given in our world right now. Venture capitalists bank on it.

We also acknowledge that a high population confers economic power. A city with a growing population is booming, and a city losing population is busted. Growth requires an expanding market. And ultimately, an expanding market requires one thing: more humans.

So we begin to see that my future isn’t utopian at all, especially since…

My future is urban

Right now, more than half of all humans live in cities. That proportion will keep growing. I see a future where the vast proportion of people live in cities—maybe everyone.

I’ll admit I’m a bit prejudiced in favor of cities. I live in downtown Toronto, the fourth-largest city in North America. I love the quality of life. Everything I ever want is within walking distance—arts, culture, sport, shopping, restaurants, parks, museums, festivals. It’s terrific, but it’s certainly not the standard ideal of a high quality of life as defined and achieved by by the Baby Boomers, and it’s not the way my Silent Generation parents lived.

The dominant dream of the mid-to-late 20th Century was to live in a suburban pastoral estate, commute in an energy-inefficient, pollution-producing exoskeleton to a stable, well-paying, pension-protected nine-to-five job, and come home to dinner prepared by an unpaid supply chain manager. That Boomer dream is already becoming history. Most people in the world never had it in the first place, and even in North America, it’s a lifestyle beyond the reach of younger generations.

This exclusively urban future will happen because providing high quality of life to the huge populations required for economic growth is only possible if those people live in highly-concentrated populations, where services can be provided with an economy of scale. But highly concentrated populations have a down side…

My future has little privacy

In a high-density city where adaptive, responsive supply chain management ensures all those value-creating humans are safe, fed, and housed, one thing makes it all work: Situational awareness. Unless the needs of a population can be monitored in real time and requirements met before a disaster happens, a high-density population isn’t sustainable. History teaches us this.

In a natural ecosystem, population growth is controlled by natural disruptions. A peak forest cannot remain at peak indefinitely—disease and fire will clear away species to an earlier state. In the same way, peak populations in animals are controlled by disease and predators. The ecosystems that support humans are also vulnerable to epidemics, war, and natural and human-made disasters.

What’s seldom acknowledged is that the disaster that looms over us right now, global climate change, is as much a threat to our economy as it is to polar bears. To survive climate change without having human culture slapped back to a pre-industrial state, we’re going to have to manage our ecosystem better. I don’t mean nature (though it’d be nice if we managed that better, too), I mean cities.

Luckily, we have the tools to do this. High resolution remote sensing and data collection allow us to manage and distribute resources in real-time, as needed, whether that’s power, water, conflict mediation, transportation, healthcare, or any other community service. These are the basic elements of smart cities, being developed all over the world right now, but they sacrifice privacy.

To many people, a lack of privacy sounds like dystopia, but to me it’s just business as usual. I grew up in a small town where everyone knew who I was. The clerk in the drugstore where I bought my Asimov’s magazines probably knew more about my parents’ divorce than I did. To me, privacy has always been mostly an illusion.

I’m not saying the privacy of others is something I would readily sacrifice. But there are tradeoffs for living in a high-density urban environment, and privacy is one of the big ones. But that’s okay because…

My future embraces difference

The future Earth I created for Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach draws on all these factors. The Earth of 2267 is post-scarcity, overpopulated, highly urban, and offers little privacy. It’s neither a utopia or dystopia, but has aspects of both (just like our world does right now). It’s a vibrant world where cities compete with each other for the only resource that matters: humans.

In the book, cities are completely managed environments known as Habs, Hives and Hells. Hells are carved out of rock deep underground. Hives are also underground but are dispersed, modular cities located in deep soil. Habs are above ground. All are independent, self-contained, completely managed human environments that eliminate the threat of natural disasters such as floods, fires, storms, and tsunamis.

Habs, Hives and Hells compete with each other for population. Those that offer the quality of life attractive to the most people are the most economically successful, but there are trade offs. You and I might want to live in Bangladesh Hell (the Manhattan of 2267), but because everyone wants to live there so personal space is in short supply. If I didn’t want to make that trade-off, I might choose to move to Sudbury Hell, deep in the Canadian Shield, where there’s not much going on but at least it’s not crowded.

In the Earth of Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach everyone chooses the city that offers the lifestyle they want, and to me, that’s utopian. Humans don’t all want all the same things. We are stunningly diverse and complex animals, and are all capable of amazing things if we have the scope to pursue the conditions of life that feed our passions. This is the world I want—a world where everyone is free to define and pursue their own dream life.

And maybe that’s why the Boomers and the Millennials in the panel were at such odds. The life the Boomers wanted (or were told they should want) is fading. That’s a scary situation. And the Millennials can see the future rising to meet them, and offering a chance create their own dreams.

Originally published in March 2018.

Kelly Robson’s short fiction has appeared in Clarkesworld, Tor.com, Asimov’s Science Fiction, and multiple anthologies including many year’s bests. Her Tor.com novelette “A Human Stain” is currently a finalist for the Nebula award. In 2017, she was a finalist for the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. Her novella “Waters of Versailles” won the 2016 Aurora Award and has been a finalist for the Nebula, World Fantasy, Sturgeon, and Sunburst awards. Kelly grew up in the foothills of the Canadian Rocky Mountains and competed in rodeos as a teenager. From 2008 to 2012, she was the wine columnist for Chatelaine, Canada’s largest women’s magazine. After many years in Vancouver, she and her wife, fellow SF writer A.M. Dellamonica, now live in Toronto. Kelly’s latest book, Gods Monsters and the Lucky Peach, is available from Tor.com Publishing.